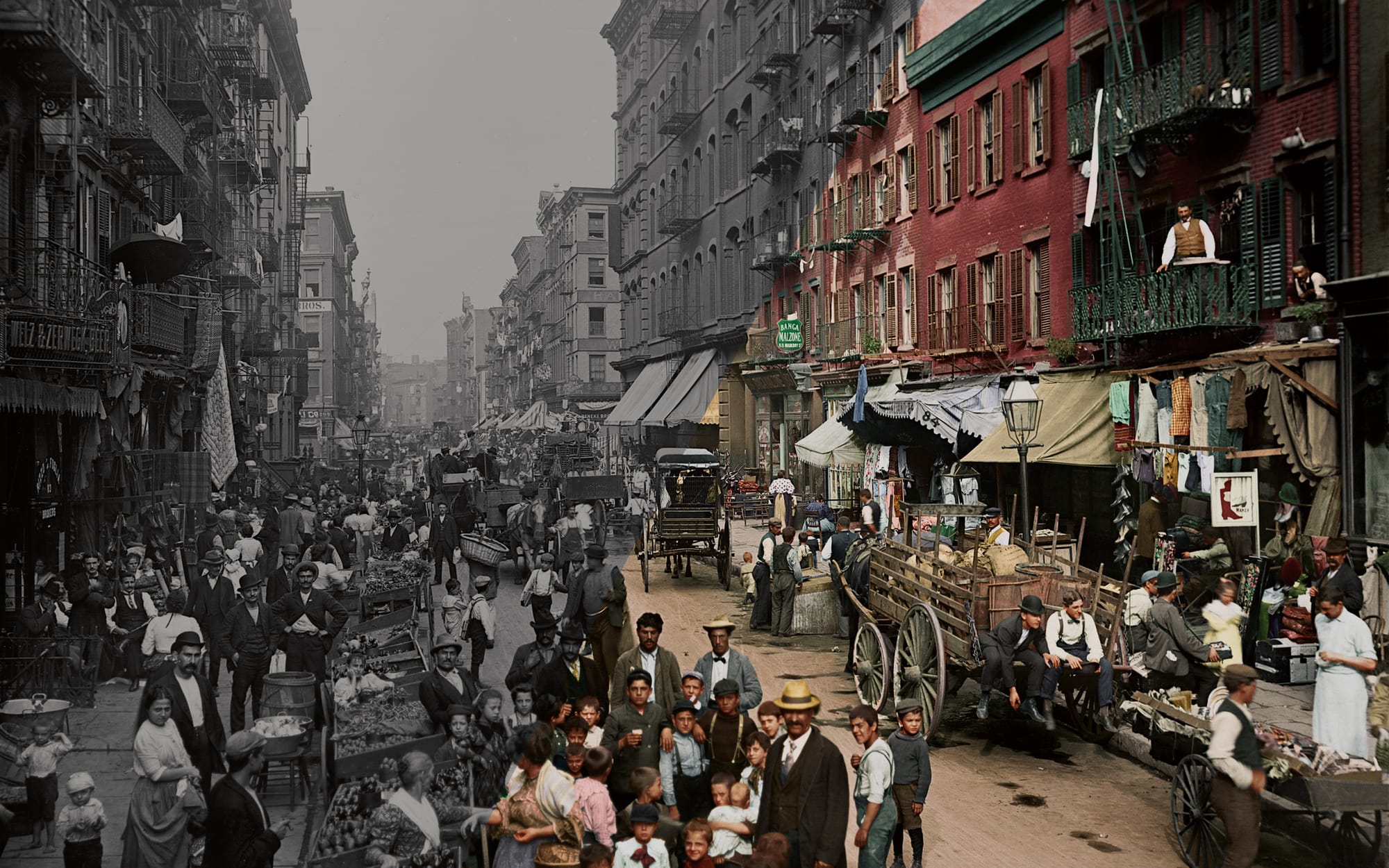

1900: Mulberry Street, New York

A glimpse into Manhattan's teeming streets at the turn of the twentieth century

“They leave their own beautiful valleys and picturesque towns possibly on account of the heavy taxation, and are to be found herded here in this land of promise.”

Words by Peter Moore

Photographs Remastered and Colourised by Jordan Acosta

As the twentieth century approached, a journalist considered the progress of the Italian community in New York City.

18 June 1896

There was a time, not so very long ago, when the organ-grinder was almost the sole representative of the ancient Roman in America.

The organ-grinder, it is true, is still to be found in New York and other cities, but ‘Little Italy’, as the Italian colony in the Empire City is still called, is, happily, no longer a haunt of lazzarone, ragpickers, and cutthroats.

In numbers along the Italian colony makes and impressive show, for according to the best authorities there are no fewer than 105,000 Italians in New York City alone, of whom 25,000 are voters. But what is far more satisfactory is the improvement in the moral and social status of the average Italian settler.

The padrones have been muzzled, if not entirely banished, and the extraordingary catacombs which sheltered the fugitive reptiles of the Old World twenty years ago in the Five Points no longer exist. The modern type of New York Italian is for the most part thrifty and industrious.

Indeed, it is stated that there are more bankers among the Italians than among any other foreigners in New York, except the Germans. As for clubs and benevolent societies, there are now no fewer than 145, including the ‘Improved Order of Red Men,’ and institutions named after Garibaldi, Torquato Tasso, and Mascagni.

There are also, of course, secret societies, but on the whole the condition of the colony justifies the optimistic view of the ‘New York Times’ in regarding the Italian element as distinctly a source of strength and satisfaction to the Republic.

This excerpt reflects the shifting perceptions of New York's Italian community in the early 20th century, charting their evolution from marginalisation and adversity to recognition as a vital and industrious part of the city's fabric.

A few years later, in the year 1900, documentarian Jacob Riis pointed his camera down a busy Mulberry Street, capturing a bustling and energetic urban scene. Riis was a social reformer who exploited photography as a means of promoting his political causes. An immigrant himself, Mulberry Street in New York City was a natural subject for him. Here, in the heart of what was starting to become known as Little Italy, he was able to document the life of the street.

In the late nineteenth century, Italians were becoming a much more visible presence in the tenement buildings of what H.G. Wells termed ‘New York's crowded littered east side’. For Christian moralists like Helen Campbell, Mulberry Street was the scene of much depravity. The ‘great bend’ in the street on a Saturday morning, she complained, presented ‘a spot as utterly un-American as anything in New York.’

The open-air market is going on, and trucks and barrows of every description line the sidewalk. A never-ending throng, through which one can barely make way, fills every available foot of walk. Tainted meat; poultry blue with age and skinny beyond belief; vegetables in every stage of wilted ness; fruit half rotten or mouldy; butter so rancid that it poisons the air; eggs broken in transit, sold by the spoonfui for omelets; fish that long ago left the water,- all contribute their share to the unbearable odor that even in the open air proves almost too much for endurance.

While Campbell was offended by what she saw, others dwelt on the vivid life and buoyant energy of the neighbourhood. Scanning this image it is possible to pick out all manner of trades and characters. A particularly striking feature of seeing the image in colour is the little flashes of colour—the green of the peppers, the red of the tomatoes—that animate the scene.

Ad: Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. Our online shop offers a wide range of collectible museum-grade fine art prints, hand-printed in England for your wall space.

ColorGraph™ presents the most incredible colorized photography bringing the past to life. From start to finish, a ColorGraph print is made with exceptional care and attention. To mark its provenance, we emboss each one in the final stage of the hand-finishing process.

These jets of life were appreciated by one journalist who described the street in the early years of the twentieth century. Many people, he wrote, retained the picturesque habits of sunny Italy, ‘the women their brightly coloured shawls and dresses, and the men their knife at the hip ready to be drawn on little provocation.’

The official statistics for January 1900 gave a total of 370,848 Italian New Yorkers. This number was rising sharply and, as another writer pointed out, it meant that New York could rightly consider itself alongside Naples, Milan and Rome as a great Italian metropolis too •

This Snapshot was originally published January 19, 2024.

His latest book was a British pre-history of the American Revolution, Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness (2023). He teaches creative writing at the University of Oxford and edits the website Unseen Histories.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store