One of History’s Great Mysteries

In this excerpt from Fall of Civilizations, Paul Cooper confronts one of the great puzzles of ancient history.

In the years before 1200 BC the eastern Mediterranean was home to a number of young but thriving 'civilizations'. Among these were powerful empires like the Hittites, Minoans and Mycenaean Greeks.

But then, in a mystery that has long perplexed modern historians, in a short space of time these empires collapsed. Most of them vanished so completely, writes Paul Cooper, 'that they disappeared from the historical record altogether'.

The Late Bronze Age Collapse

For full references and notes please consult the published book

From the ashes of the earliest known civilization, Sumer, a host of successors arose in the millennium that followed. By 1200 BCE, the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea were ruled by a diverse scattering of kingdoms, minor empires and city states.

Languages and cultures mingled as trade routes criss-crossed land and sea. Markets bustled in the thriving cities of Ugarit, Hattusha, Mycenae and Babylon, and the Mediterranean experienced a golden age of literacy and culture. But within just a few decades, every one of these cities lay in ruins. Their stones were scattered, their libraries burned, their people left unburied in the streets.

The world as it once was came to an end, and only ash and desolation were left behind. This was one of the worst disasters of ancient history, an event that historians have come to call the ‘Late Bronze Age Collapse’ — and exactly what happened is still one of history’s most fiercely debated mysteries.

The ruins of the city of Hattusha are a melancholy sight: crumbling walls of grey limestone stand out against the tawny yellow grassland and rocky outcrops of the surrounding hills.

Even now, one look will tell you that Hattusha was once a mighty fortress, built in the rocky Çorum province of the Black Sea Region of Turkey, within a great bend of the Kızılırmak River. Its double wall was defended by more than a hundred towers, its thick gateways decorated with carved sculptures of lions.

For centuries, this was the prosperous capital of the Hittite Empire. But if you were to dig down into the ruins of Hattusha, you would find a thin black layer right above the floor level of its buildings. This layer is made up of ash, charred wood and rubble scorched in a fierce fire, and it dates to around 1200 BCE. Archaeology paints a picture of total destruction: walls and roofs collapsed, bricks shattered and melted.

After that event, the archaeological record ends. Except for occasional signs of a few scattered scavengers eking out an existence among the rubble, the ruins of Hattusha remained empty for centuries — a haunted place, where it seems most feared to go.

We find the same evidence 20 kilometres north of Hattusha, at the site of the ancient city of Alaca Höyük, where the Hittites buried their kings in opulent tombs. Like Hattusha, it is completely covered by ash and rubble at the same level. And 100 kilometres to the east of that, another fortified Hittite town known as Maşat Höyük, with a strong citadel and spacious palace, was also burned around the same time.

In nearby Karaoğlan, you can find arrowheads littering the earth like fallen leaves, and the bones of men, women and children left lying in the streets, right where they fell over 3,000 years ago.

In fact, almost anywhere you go in the Eastern Mediterranean, across an area spanning over 1,000 kilometres, you will find this layer of destruction. Archaeological evidence is quite explicit: at some point between 1200 and 1100 BCE, civilization in this region simply came to an end. The historian Robert Drews puts it succinctly:

Within a period of forty or fifty years at the end of the thirteenth and beginning of the twelfth century [BCE] almost every significant city in the eastern Mediterranean world was destroyed, many of them never to be occupied again … It is safe to say that for a long time after the year 1200 [BCE] there were no cities in the [Eastern Mediterranean] area.

— Robert Drews

It took some of these areas nearly a thousand years to recover. Powerful and well-established empires like those of the Hittites, Ugarit, the Minoans and the Mycenaean Greeks collapsed so completely that they disappeared from the historical record altogether, and their descendants were left to live among the ruins.

One of the ways in which the memory of the Late Bronze Age Collapse may have survived is through the epic poetry that was composed about this time. The most famous of these relates the destruction of a walled city in the Eastern Mediterranean called Troy.

The epic poems known as the Iliad and Odyssey are attributed to the author Homer, who may or may not have existed. Recent scholarship now generally holds that these epics were passed down as oral poetry for centuries through the period known as the Greek Dark Ages, which followed the chaos of the Bronze Age Collapse.

These poems survived by word of mouth, with each poet-singer using astonishing skills of memory to recite them, lengthening and embellishing them along the way, until they were finally written down by an anonymous scribe around the eighth century BCE.

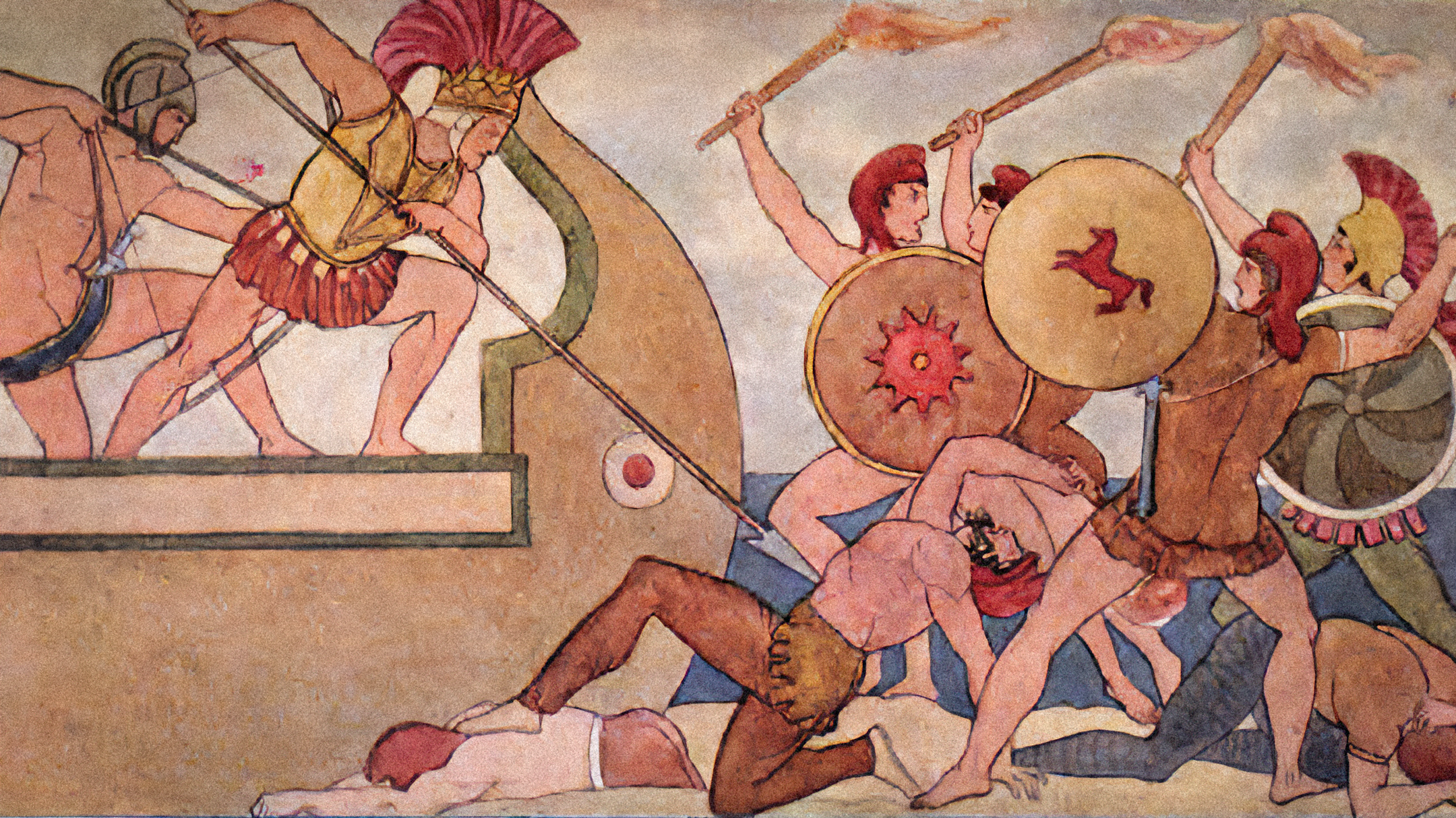

The poetry of the Iliad especially relates the story of a ten-year war that took place in the Eastern Mediterranean, and which occupied much of the warrior classes of Greece. This war was supposedly led by Agamemnon, a king of the Greek city state of Mycenae.

In the second millennium BCE, Mycenae was one of the major centres of Greek civilization, and from around 1400–1200 BCE was the predominant power of the Peloponnese.

Lying about 90 kilometres south-west of Athens, it was a military stronghold that held sway from its mountainous perch overlooking the plains of Argos, and had a population of over 30,000 people at its height.

Like Hattusha, its citadel gates were decorated with carved stone lions, and its people made armour out of ivory taken from the tusks of wild boars. Over a millennium later, in the second century CE, the Greek travel writer Pausanias wrote breathlessly about his visit to its ruins, the large stones of which were so impressive that he believed them to have been built by giants:

The wall, which is the only part of the ruins still remaining, is a work of the Cyclopes made of unwrought stones, each stone being so big that a pair of mules could not move the smallest from its place to the slightest degree. Long ago small stones were so inserted that each of them binds the large blocks firmly together ...

For a long time it was thought that the Trojan war was an invention of a poet’s imagination, and that the city of Troy itself was a myth — but that all changed with the discovery of the ruins of Troy at the end of the nineteenth century, at a place called Hisarlık at the mouth of the Dardanelles in what is today Turkey.

This location would have placed Troy on the periphery of the Hittite Empire, and as a major rival to Mycenaean power.

.jpg)

Many scholars now believe that the Trojan War as related by Homer does reflect real events, or at least a composite of several events, filtered through the lens of mythology and oral storytelling.

The historian Eric Cline points out that a Hittite artefact known as the Milawata letter describes a conflict that seemingly occurred between the Hittites and the Mycenaeans over a city that they called Wilusa — which may have been the Greek Ilion, or Troy.

This conflict may not have been particularly large, but in the time between the real event and the writing of the epics, the entire region underwent the catastrophe of the collapse.

Over that period, these epics may have preserved at least in hazy form an authentic memory of those days — not just a clash between two powerful Bronze Age empires, but the feeling of apocalypse that must have washed over the region, the trauma of a period of warfare and destruction that seemed to dwarf all others.

The site of Troy has now been extensively excavated, and we have learned that throughout the Bronze Age, Troy was indeed a grand city much as Homer describes. It was topped with an impressively fortified citadel, and contained artefacts that suggest trade links to the Hittites, Assyrians and Babylonians.

.jpg)

This layer of the city’s archaeology is known at Troy VI, and it lasted from about 1750 BCE until about 1300 BCE. According to the Greek epics, its walls were built by the gods Poseidon and Apollo, and in reality they were certainly impressive: 9 metres high, with towers soaring up to 18 metres.

Around the citadel replete with royal palaces, a long curtain wall enclosed a larger urban area. But unfortunately for historians, the ruins of Troy are strangely silent — that is, there has been almost no writing uncovered in any excavations of the city, and it’s unclear even what language the people of Troy spoke.

The grand royal city of Troy VI was destroyed around the year 1300 BCE, possibly by an earthquake — there is widespread damage to the foundations of the buildings, and some sign of fire damage to the city’s stones — but others argue that it could have been sacked, and that this is the event that Homer’s Iliad remembers.

After this disaster, people rebuilt many of the monumental palaces, and reinhabited the city in a somewhat diminished form — but then around 1190 BCE, the city was burned again, right as that wave of destruction passed over the whole region. Here, significant traces of fire can be found on its stones, while human remains were found in houses and in the streets.

Near its north-western ramparts, a human skeleton with skull injuries and a broken jawbone was unearthed, and bronze arrowheads litter the ground in the citadel. In fact, it seems Troy was burned twice towards the end of the thirteenth century BCE.

It’s not clear who the perpetrators of this massacre were — but we can imagine that the poetry of the Iliad captures something of the violence of warfare in that time.

Then rose too mingled shouts and groans of men

laying and slain; the earth ran red with blood.

As when, descending from the mountain’s brow,

Two wintry torrents, from their copious source

Pour downwards to the narrow pass, where meet

Their mingled waters in some deep ravine,

The weight of flood, on the far mountain’s side

The shepherd hears the roar; so loud arose

The shouts and yells of the commingling hosts.

The Hittitologist Trevor Bryce speculates that it was this final abandonment of Troy’s population centre that inspired Greek poet-singers to assemble the material of the Iliad:

All this contributed to the making of the epic: a long tradition of conflicts between western Anatolian peoples and the Mycenaean Greeks … the final abandonment of the citadel of this state … They now saw before them Troy’s ultimate fate — its destruction and abandonment.

The Greek city state of Mycenae would itself face a similar fate. By 1200 BCE, its power was waning — but then, within a short time, all the palace complexes of southern Greece, including Mycenae, were burned to the ground ■

He writes, produces and hosts the Fall of Civilizations podcast, which has charted in the top ten British podcasts, and since its launch in 2018 has garnered over 100 million downloads and over 1 million YouTube subscribers.

Fall of Civilizations: Stories of Greatness and Decline

Duckworth, 25 April, 2024

RRP: £25 | 400 pages | ISBN: 978-0715655009

"A treasure trove of myths and terror… Atmospheric as hell… Immersive."

– The Times

Based on the podcast with over 100 million downloads, Fall of Civilizations brilliantly explores how a range of ancient societies rose to power and sophistication, and how they tipped over into collapse.

Across the centuries, we journey from the great empires of Mesopotamia to those of Khmer and Vijayanagara in Asia and Songhai in West Africa; from Byzantium to the Maya, Inca and Aztecs of Central America; from Roman Britain to Rapa Nui.

With meticulous research, breathtaking insight and dazzling, empathic storytelling, historian and novelist Paul Cooper evokes the majesty and jeopardy of these ancient civilizations, and asks what it might have felt like for a person alive at the time to witness the end of their world.

"Paul Cooper's histories of fallen civilizations are brilliantly written: clear, compelling, and ultimately chilling as we are forced to accept the lost genius of ancient cultures and the inevitable ruination of our own. Full of fascinating detail and nuanced findings, you need to read this book"

– Cal Flynn

With thanks to Angela Martin