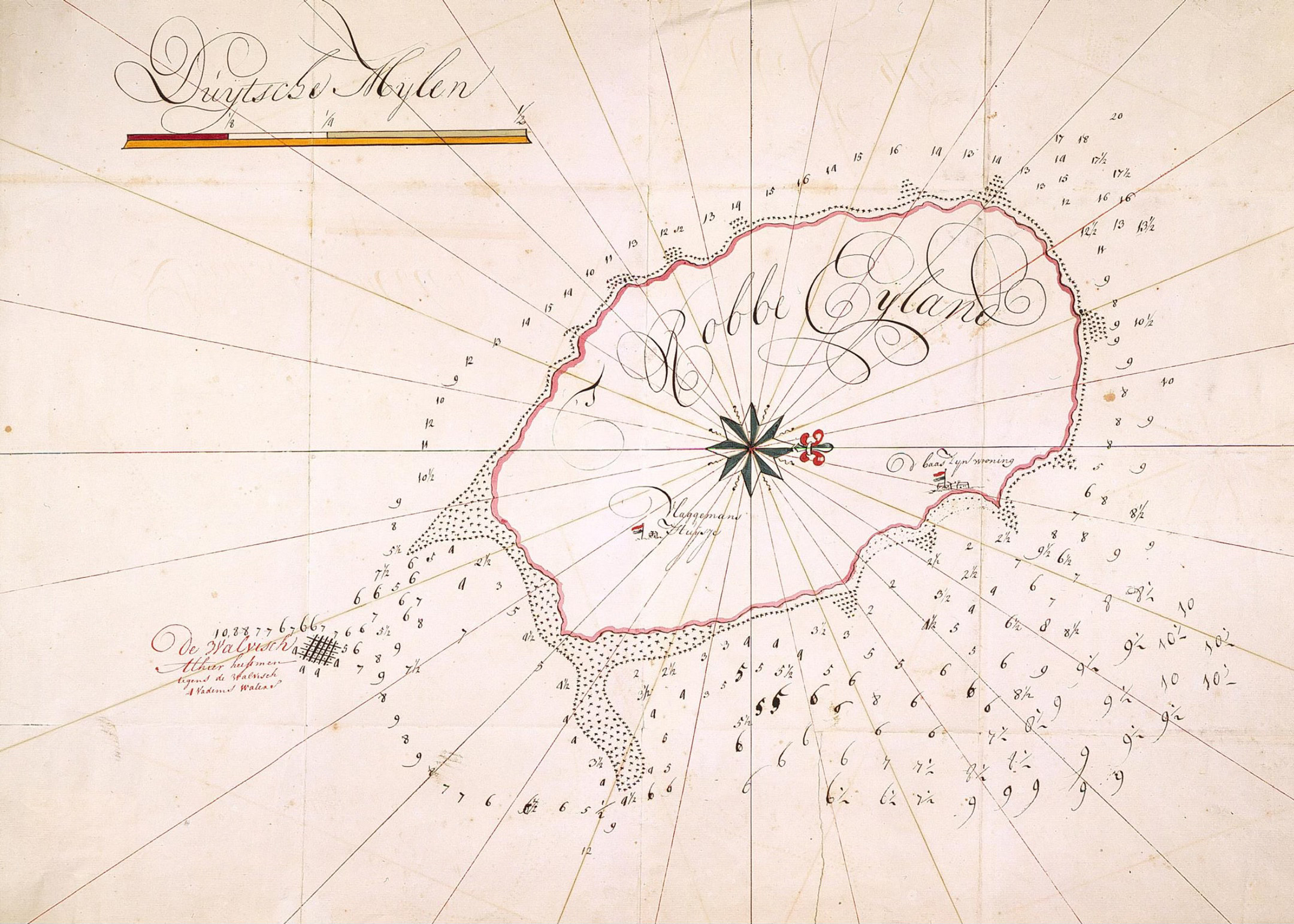

The Leprosarium at Robben Island

Oliver Basciano recounts a lesser known part of Robben Island's complex history

Since the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, Robben Island, off Cape Town, has been celebrated as a place where the human spirit has triumphed over adversity.

But long before Mandela began his 27 years of imprisonment, the island held many other people captive. From 1845 onwards, in particular, leprosy patients were taken to the island.

In this excerpt from his book, Outcast, Oliver Basciano evaluates this history.

For references please consult the finished book.

I never find out whether you are supposed to wander Robben Island alone. To duck out at the end of the guided tour, to miss your ticketed ferry back, to return on the afternoon crossing to Cape Town instead.

It seems harmless enough, just a question of catching up with the later waves of visitors arriving at this rocky outpost with the regularity of the bay’s ferocious swell. Table Mountain lurks in the clouds as I scurry at pace past the family steak restaurants and fancy shops of the city’s harbourside development.

I arrive just in time to cross the metal ramp onto the ferry, catching the tail of the hundred or so sightseers from around the world who have already boarded. Soon the Krotoa is reversing out of the harbour, water spraying against the sealed windows. The songs of South African freedom that play over the boat’s PA system give way to an introductory video which accompanies the crossing of the bay.

With the journey just twenty minutes, the film covers Robben Island’s early history at speed: first landed by the Portuguese in 1498, it was used by the British and Dutch as a refuelling station on their colonial voyages. When the latter established settlements on the Cape in the seventeenth century, they immediately identified these five square kilometres as the ideal place to jettison the troublemakers of their new outpost.

Formalised as a prison, the coloniser shipped over former kings, princes and religious leaders of its possessions in the East Indies, abandoning them alongside the homegrown undesirables. The seals that the colonial masters named the island after – the Dutch ‘r’ rolled to an almost English ‘w’, the second ‘b’ hard – soon faced extinction, the prisoners hunting and skinning them as means of survival.

When the British took possession two centuries later the island continued to be used as a dumping ground for anti-colonial insurgents. The rebels of St Helena, Bencoolen, Penang, Singapore, Malacca, Burma, Aden and Mauritius were landed here by the East India Company. One group, banished after the Cape frontier wars, tried to escape. Some drowned, others died as they were recaptured, most were returned before being beheaded and their heads displayed on poles along the shoreline.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the prisoners had left and the island’s new residents were arriving: the Cape’s leprosy patients, who were forced to call this home for almost a century while the mainland was completely reconfigured through waves of colonial management and mismanagement.

The Krotoa video is in fact skimpier on detail than this expanded telling; for the most part, as we cross the choppy waters, the South Atlantic a bubble bath of foam, the film concerns itself with the outpost’s most infamous role: a maximum-security prison to the heroes of South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle.

If this boat trip has been made by patients and political prisoners alike, then likewise the laws against leprosy helped navigate South Africa’s slide into racialised segregation, the cordon sanitaire providing a blueprint for prejudice. Robben Island: such a byword of discrimination and resistance that the real place risks all but disappearing, a ‘rhetorical space’, as the professor of language Richard Marback has called it.

In August 1883, Alexander Abercrombie, a Scottish-born member of the Board of Health and the colony’s legislative assembly, appeared before a select committee on the subject of leprosy. ‘I can speak merely from what I see daily in my rounds about the streets of Cape Town, and I can say that it is rapidly increasing… amongst the lower classes; chiefly the coloured races.’

Robben Island had been used to house leprosy patients from 1845 when, largely for budgetary reasons, a group of patients were moved from another camp long established in the Hemel En Aarde Valley (all trace of which has disappeared under the pinot noir vineyards that the inclines are now chiefly famed for).

Admission to the leprosarium remained voluntary, at least in theory, and the population rarely peaked beyond fifty, confined ‘chiefly to the pauper class’ who had little other option than to submit themselves to the hands of the state. They could come and go, and frequently hitched lifts with passing fishing fleets to visit family on the mainland.

Abercrombie’s contribution was part of a debate over changing the law to establish forced segregation. ‘A specific bacillus has lately been found in leprosy, and this will, no doubt, in course of time, throw much light on the cause of the disease,’ Abercrombie told his political colleagues.

‘It would be communicated to a person who came in contact with a leprous person if he had a sore or an abrasion. For instance, if he were to touch a leprous person with sore fingers; use the same knife or fork; or drink out of the same glass.’

On questioning, he admitted that he had come across many married couples in which one half had the disease but the other did not, but that was just a matter of ‘constitution’, therefore, personally, ‘I would not like to sleep in the same bed as a leper.’

His testimony came as the Cape had already introduced its first public health act in 1883, in response to a smallpox outbreak, which gave administrators the power to clear areas of the city in case of an epidemic.

Following the evidence of Abercrombie and others, the 1884 Leprosy Repression Bill similarly allowed the removal of individuals, but in this case the authorities did not have to declare any mass health emergency.

Both were sweeping new powers for the government but neither were put into practice immediately; the former was reserved for the next big calamity, the latter batted between administrators local and in London, again with an eye on the purse strings, knowing that the maintenance of what would surely be a much-enlarged Robben Island operation came at a price.

The election of Cecil Rhodes domestically, changed the equation again. With the ‘leper scare’ in full swing globally, within a year of coming to power Rhodes ratified the leprosy segregation law in 1891: those with signs of the disease were pulled from their homes in the likes of District 6 without warning, often in handcuffs, the authorities worried that otherwise they might go into hiding.

‘There is a descent upon the house . . . there is no time to do anything – the ambulance is waiting, therefore the person must go. In many cases it is a removal for life, and it has to be done in five minutes,’ one Church of England minister complained, citing a particularly distressing case in which a twenty-year- old woman was taken by a group of plain-clothed men.

‘The mother flew into a temper and said she would not let them take her daughter that day. Then they sent for the police and of course there was a disturbance in the street.’

Most doctors went along with this persecution, but not all were convinced and the global debate over contagion and freedom played out through the harried lanes of Cape Town. Robert Forsysth was one such medic who was willing to risk sanctions for failing to report a case if he assessed it to be particularly mild.

Admitting such a practice, the local doctor defended himself by saying that though he was bound by the resolutions of the leprosy congresses in Berlin and Bergen that segregation was necessary, in Norway ‘even those in asylums are allowed to go about the roads’ and ‘I think more of the liberty of my patients than of paying a small fine’.

His peers were dismissive: ‘They deal with a different class of people,’ a colleague stationed on Robben Island countered in regard to the Nordic country. The Medical Officer for Health was even more explicit in the racism. ‘Here you have a very different population to deal with. A people largely composed of native and coloured, unreliable, indifferent to the dangers of the disease, ignorant and devoid of the simplest knowledge of hygiene.’

Within a year the number of those who were interned on the island, outcasts who foreshadowed Nelson Mandela, had climbed to 413; by 1915 there were 600 people living on the rock amongst the foaming Pacific swirl, no hope of return to the mainland •

This excerpt was originally published July 23, 2025.

Outcast: A History of Leprosy, Humanity and the Modern World

Faber, 19 June, 2025

RRP: £20| ISBN: 978-0571384303

“Remarkable . . . grippingly and humanely recounted” – Philippe Sands

The story of leprosy is the story of humanity. It is a story of isolation and exclusion, of resilience and resistance, one which has permeated global cultures in myriad ways for thousands of years, dividing the world into the 'clean' and the 'unclean'.

Oliver Basciano's journey to demystify leprosy takes him from the Romanian border, the hinterlands of Brazil and the fringes of Siberia to the Japanese archipelago, Robben Island and the northern provinces of Mozambique. It reveals the image of medieval leprosy to be a nineteenth-century myth invented to justify gross mistreatment of patients, a blueprint used for further state-sanctioned stigma: colonialism and racism, religious and economic exploitation.

Basciano meets those living with leprosy today, those exiled to various leprosaria around the world and forced to find homes away from home; he hears stories of community and perseverance in the face of grave circumstances, of lives bound to each other through shared experience and a refusal to be cast aside.

A work of outstanding empathy, Outcast shines new light on the human condition, asking: does a society's sense of itself always rely on ostracisation?

“A new kind of travel book - across continents and, more importantly, across the partitions that separate the healthy from the damned - Outcast is a revisionist history that makes you realise, when you turn its last page, how differently you look at the world than you did when you first cracked its spine”

– Benjamin Moser

“Shocking, moving and sensitive . . . Outcast reveals a medical scandal on a colossal scale. More the story of a stigma than the story of a disease, it outlines how leprosy has been used throughout history and across the globe as an excuse for abominable discrimination and treatment. But it also illuminates a courageous counter-movement led by sufferers to reclaim their dignity and correct centuries of abuse . . . compelling and disturbing”

– Times Literary Supplement

With thanks to Lauren Nicoll. Author Photograph © Anita Goe.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store