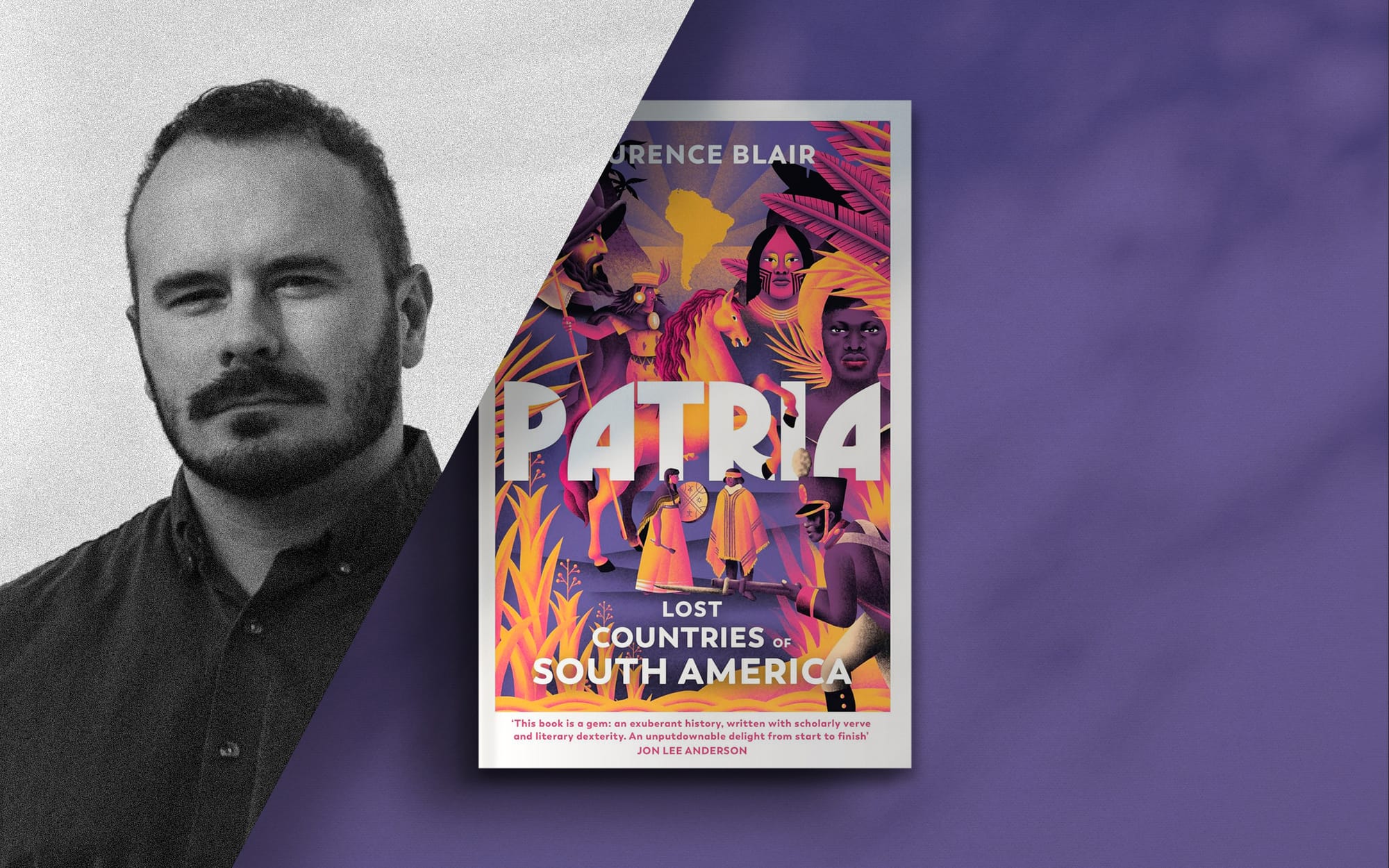

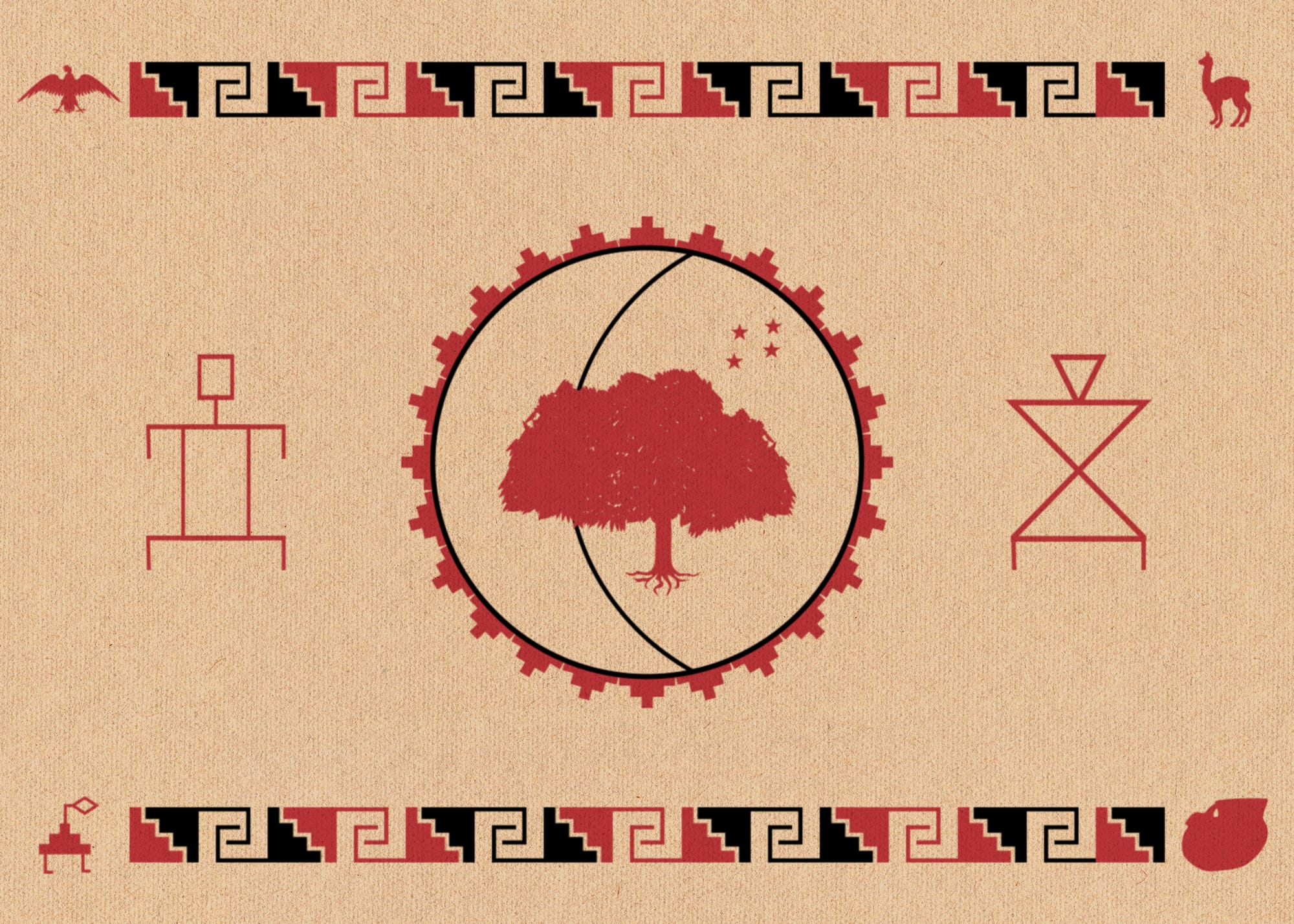

Patria: Lost Countries of South America with Laurence Blair

South Americans are looking at their continent's history afresh, explains Laurence Blair

Few in the Global North know much of South America's history.

Those who do are most likely to be familiar with a traditional narrative, where the European conquests of the sixteenth-century were followed by the all-powerful empires of the seventeenth and eighteenth and the elite-led revolutions of the nineteenth.

Laurence Blair's debut, Patria: Lost Countries of South America, sets its sights beyond this. As he explains in this interview, he has spent a decade travelling from the jungles of Paraguay to the favelas of Rio and remote islands off Peru, in search of a new perspective on this old story.

Unseen Histories

As well as an historical investigation, Patria is very much a personal odyssey. Your travels across the continent bind the story together. Can you tell us a little about this and about some of the provoking encounters you had on the way?

Laurence Blair

Patria definitely isn’t a traditional history book. I cite hundreds of historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists, and I draw on material from dozens of libraries, archives and museums across Europe and South America.

But I’m a journalist, not an academic. That gives me a certain freedom, but also a responsibility.

I couldn’t write about these largely forgotten places without travelling to them, seeing what remains, hearing from those who live there, and bringing the reader with me on that journey.

I joined a young Venezuelan family setting out into the lawless Darien Gap: some of the eight million people to flee the collapsing Boliviarian Revolution in their homeland.

I dropped by the thatched homestead of a Mapuche independence activist who told me I was no longer in Chile, but Wallmapu. I sat around the fire with Indigenous Amazonians in a ruined palace in Rio de Janeiro from where scientific expeditions set out to forcibly contact their ancestors. And I descended in a military helicopter into marijuana plantations in the jungles of northern Paraguay where the continent’s bloodiest-ever war came to an end.

Everywhere I went, South American history was clearly not confined to textbooks but was leading a fiercely contested afterlife.

Unseen Histories

Your subject is the ‘lost countries’ of South America. One of them, thriving at about the time of the Battle of Agincourt, was the Chincha Kingdom. What was that?

Laurence Blair

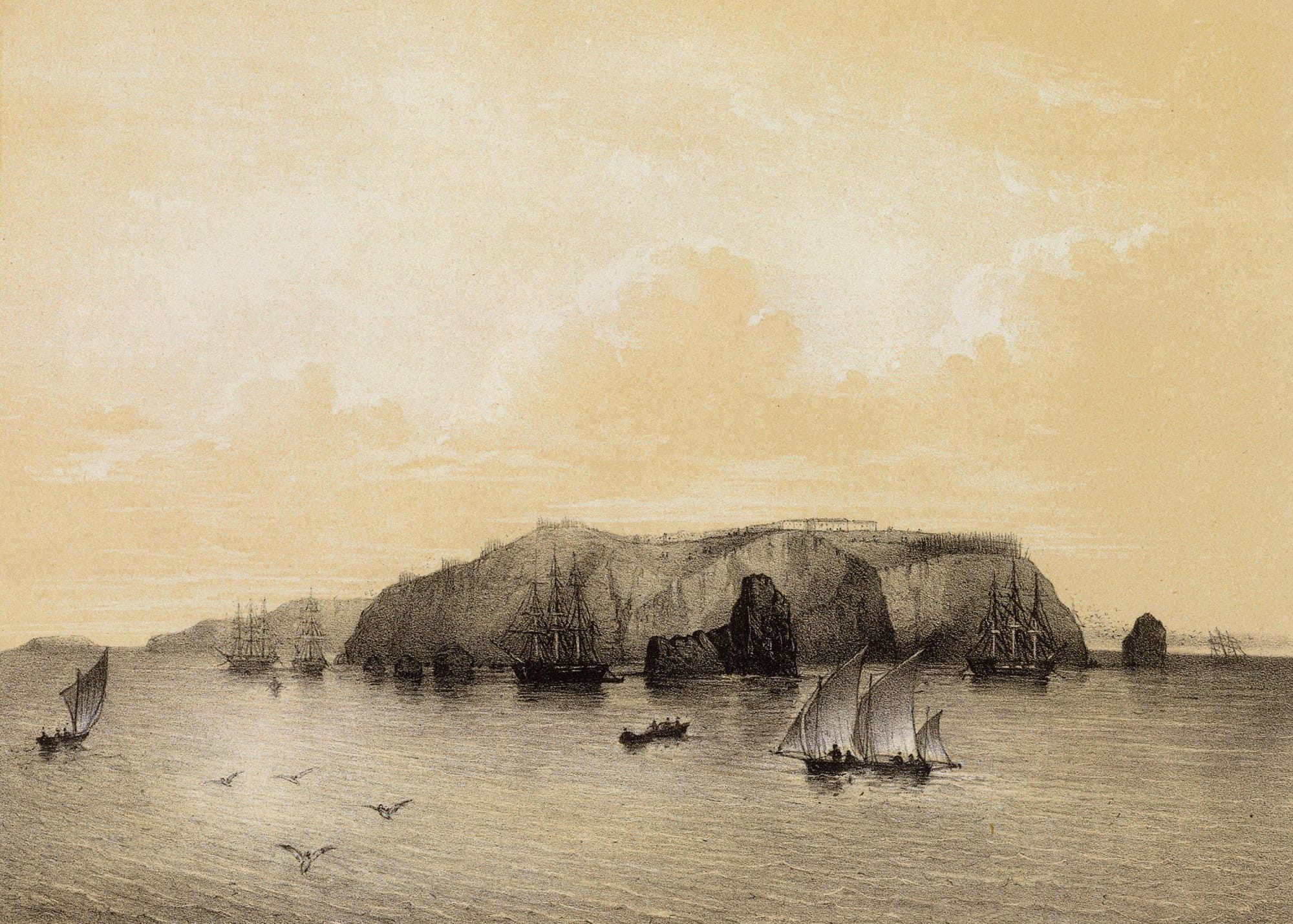

The Chincha were fishers, farmers, weavers, traders and seafarers who built great pyramids of adobe blocks in the deserts of southern Peru around 700 years ago, and plied the South American coast well past the equator. Though little known today, they were given special privileges after being conquered by the Incas: their ruler was carried in a litter beside the emperor Atahualpa.

The most intriguing explanation for this lies twenty miles off the coast. The Chincha Islands were home to the world’s greatest deposits of guano – dried bird droppings. Until the invention of chemical fertilisers, guano was like gold dust. It can quadruple agricultural yields after a light dusting. The Chincha seem to have been stewards of the seabirds and guardians of the guano: paddling out and carefully harvesting the malodorous powder without putting the millions-strong flocks of pelicans, cormorants and boobies to flight.

Guano, it seems, buttressed the Inca Empire by enabling its barren Andean slopes to bloom with enough produce to feed 14 million subjects. The Chincha were decimated by the diseases brought by Europeans, but some elites maintained their position under Spanish rule. And the islands were the epicentre of a global guano rush in the mid-1800s that even sparked war between Spain and four South American countries.

Unseen Histories

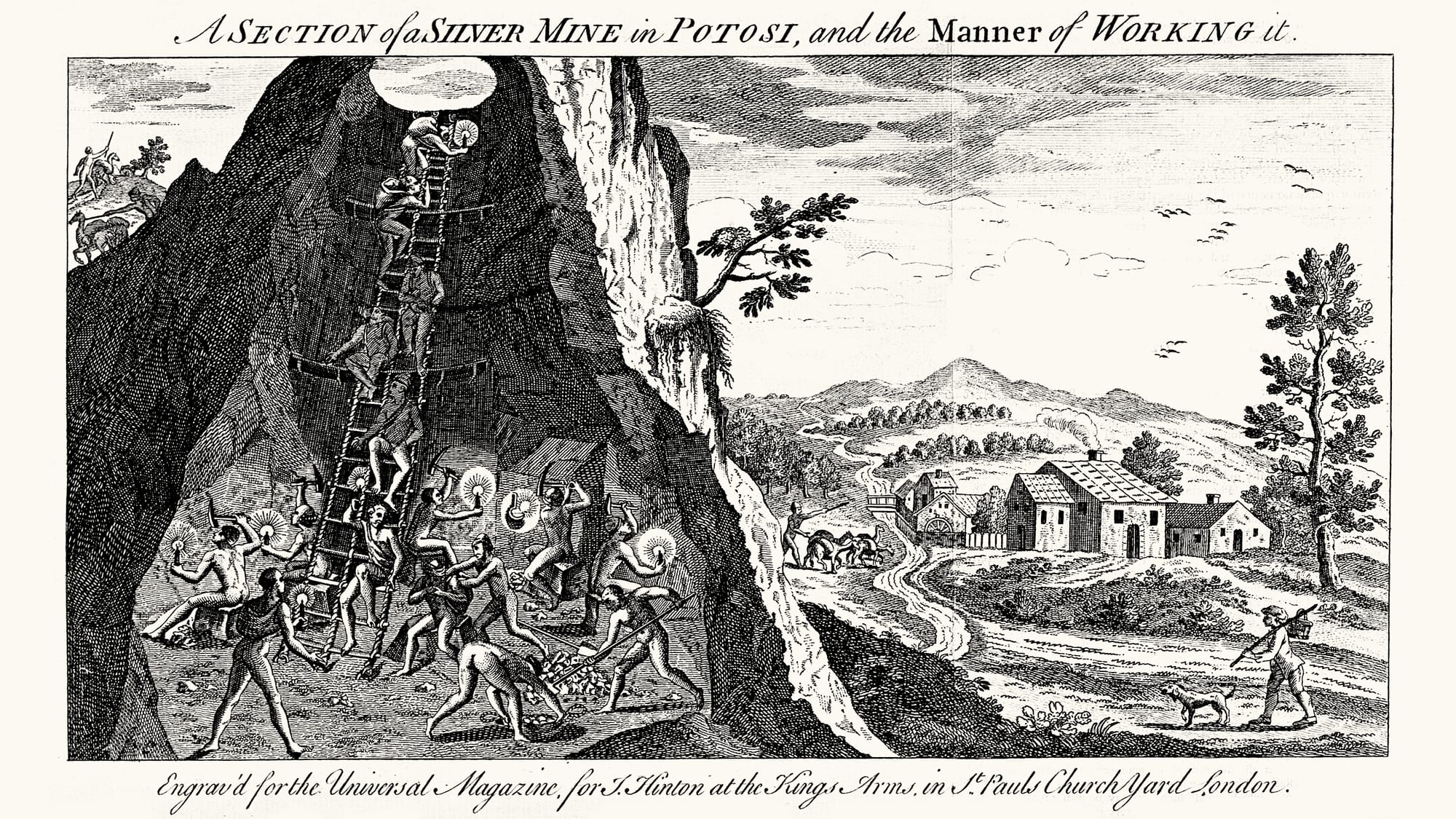

Much of Patria concerns the European effect on South America. But Diego Gualpa’s discovery of the Cerro Rico silver mine in 1545 would have a powerful effect on the rest of the world, wouldn’t it?

Laurence Blair

The discovery of Potosí silver represents the dawn of globalisation. The mountain, in present-day Bolivia, contained perhaps the richest veins of the precious metal anywhere on the planet.

By 1810, nearly a billion pesos had been hacked out of the mountain by Andean labourers, and loaded onto galleons bound for Seville and Manila. They slip through the palms of Flemish traders, English pirates and Moroccan corsairs, Ottoman caliphs and African kings. The glut of pieces-of-eight even triggers hyperinflationary episodes in Mughal India and Ming-dynasty China.

The biggest spender by far was Spain. Gualpa’s paydirt underwrites the credit of the world’s first global superpower, making its monarchs and muleteers filthy rich – at least on paper. Yet Spain’s domestic industries stagnate as a result, leaving the country an impoverished backwater once its colonies break free. You could almost consider it the curse of 'the mountain that eats men.'

Unseen Histories

As with Francisco Pizarro and the Incas, people are familiar with a story of eradication. But Patria includes many examples of endurance too. Can you tell us of some of them, like the Quilmes?

Laurence Blair

It’s often said that Europeans 'conquered the New World' through guns, germs and steel. The reality is that they failed pretty dismally. By 1800, about half of the Americas consisted of independent realms of native peoples or the descendants of fugitive Africans: like the Mosquito Kingdom of coastal Central America, or the wealthy Mapuche warlords, merchants and statesmen whose Patagonian dominion stretched across the Andes from the Pacific to the Atlantic, and who freely raided to within a day’s ride of Buenos Aires as late as the 1870s.

The Quilmes held out in high Andean desert valleys until the 1660s. Then, they went down fighting, with an Andalusian conman – who claimed to be the rightful Inca – as their figurehead.

In colonial Argentina’s own Trail of Tears, the Spanish forcibly marched the survivors some 900 miles to Buenos Aires. The traditional account is that the suburb and beer of the same name are all that’s left of the Quilmes. But in recent years, the ruins of their ancient city have been (re)occupied by a community identifying as their descendants.

It mirrors a broader revival of native identity across South America. Not only has the Argentine population claiming Indigenous descent doubled in 20 years, to 1.3 million in the 2022 census. Several peoples long declared 'extinct', like the Selk’nam of Patagonia, have re-emerged.

I’ve met Peruvians who identify as Inca. And beyond questions of ethnicity is the enduring cultural inheritance of pre-Columbian civilisations. To take one example: the incredible diversity of potatoes, tubers, grains and fruits painstakingly improved by ancient Andeans that have powered Peru’s recent rise to culinary superstardom.

Unseen Histories

One of your interviewees talks about the Amazon being a ‘domesticated forest’. What is the new research that has allowed him to come to that conclusion?

Laurence Blair

It’s now becoming clear that the pre-Columbian Amazon wasn’t a pristine 'wilderness' but home to millions of people living in sophisticated, urbanised civilisations.

Early in 2024, archaeologists announced the discovery – thanks to Lidar aerial surveying technology – of an 'Amazonian Rome' of at least 30,000 people that flourished in lowland Ecuador some two thousand years ago, and whose highways, terraces, and 6,000 pyramids and platforms were hidden under the canopy until recently.

For me, the most fascinating discoveries are those suggesting the world’s largest tropical rainforest was moulded by human hands. Archaeobotanists like Charles Clement have identified at least eighty-three Amazonian species – manioc, sweet potato, Brazil nuts, peppers, fruits, palms, tobacco, and even cacao and rubber – that were domesticated by pre-Hispanic peoples, and a further 5,000 that were exploited by them, from at least 6000 BC onwards.

What’s more, ancient Amazonian agro-foresters propagated these useful species across the biome, transforming it into a living larder that restocked itself. It still provides sustenance for forest communities and uncontacted tribes to this day.

Unseen Histories

The revolutionary era that began in 1776 blazed a trail through South America in the early years of the nineteenth century. You note that ‘sixteen independent nations burst into existence in barely thirty years’. Can you explain how the traditional view of that period is ‘fast collapsing’ today?

Laurence Blair

For centuries since, South America’s Age of Revolutions was seen through the 'great men' prism. Figures from the criollo or European-descended elite like Simón Bolívar – the Venezuelan liberator – and his Argentine counterpart José de San Martín got the lion’s share of the credit for delivering independence from Spain.

But as San Martín himself made clear, the cause depended on the bravery and convictions of the masses. An army of formerly enslaved and self-emancipated soldiers marched with him over the Andes, defeating crack Spanish regiments and liberating Chile. Mixed-race gaucho guerrillas – including the prison-breaking combat nurse María Remedios del Valle, and the hard-riding lieutenant-colonel Juana Azurduy – held royalist armies at bay in the mountains of Bolivia and Argentina for a decade.

Recent scholarship has also shown how the intellectual underpinnings of independence were profoundly (Latin) American. The pan-Andean rebellion triggered by Túpac Amaru II in 1780 was greater and deadlier than the uprising simultaneously unfolding in the Thirteen Colonies. Revolutionary Haiti provides inspiration as well as armaments.

And many patriots are fired up by legends of Inca grandeur and Mapuche resistance: The Royal Commentaries of the Incas and La Araucana, centuries-old historical tomes, are dusted off to serve as a kind of 'little red book' for South American revolutionaries.

Unseen Histories

In 1815 Simon Bolívar fantasised about uniting the various nations into a single patria. Was this ever any more than a utopian dream?

Laurence Blair

The vison of a united South America was much more widespread than traditionally believed. In 1816, for example, San Martín and other influential criollo patriots threw their weight behind a remarkable scheme. They planned to pluck a descendant of the Incas out of obscurity and enthrone him in Cusco, the former Inca capital. There, he would reign as a constitutional monarch over a United States of South America that would knit together the provinces of Spanish America, overthrow the powers of the Old World and stand up to the emerging one to the north.

It’s clear that this plan drew on a groundswell of popular support, galvanising resistance against royalist invasions of what is now Argentina. Had Bolívar agreed to work with San Martín, they might have been able to forge this federal, more egalitarian vision for the continent.

Yet Paraguay, Uruguay, Buenos Aires and Imperial Brazil never subscribed to it. Though Latin America was united by a common Catholic inheritance and Iberian languages, it was divided, Bolívar admitted, by 'distant climes, diverse circumstances, opposed interests' and 'dissimilar characters'. The distances were too great, topographies too confounding, local powerbrokers too parochial.

That said, Latin American leftists still pay lip service to the patria grande. Musicians, artists and activists talk of Abya Yala, a unified American continent. The form that the United States and the European Union currently take would have been unthinkable two hundred years ago. So who knows what could happen in the future?

Unseen Histories

We are familiar with places like Bahia in Brazil being a centre of the slave trade, but not quite so much with Buenos Aires. Yet you point out that in 1800 Africans and Afrodescendants made up around a third of the population of the city. What is the legacy of that?

Laurence Blair

It’s a sensitive subject for some. But the historical record is pretty clear: Buenos Aires, albeit not on the same scale as Rio or Salvador de Bahia, was a major slavers’ port: some 300,000 enslaved Africans disembarked there between 1585 and 1812.

Well into the 1800s, diarists record hearing the gossip, songs and laughter of African dustmen, piano tuners, and washerwomen in the streets of Buenos Aires. Afrodescendants had their own churches and fraternities called 'nations' and were leading literary, political and military figures. Once the trans-Atlantic trade in enslaved people stopped, the Black population gradually shrank, largely due to inter-marriage with Indigenous and European-descended populations.

Today, even Argentine presidents routinely deny that Black people exist in Argentina: 'that’s a Brazilian problem,' to quote one, or 'Argentines descend from the boats from Europe,' to cite another. But if you spend any time in the country, particularly in working-class areas, you can see that’s not entirely true. Regional slang is peppered with African-origin words like quilombo, which originally meant something like a war camp but now means 'a mess.' And tango, the iconic musical genre, has its origins in Black, working-class portside neighbourhoods in Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

Unseen Histories

Nostalgia seems to be a very active force in South America politics. You write about the powerful fixation on its ‘blood stained backstory’. Is this as strong as ever or can you detect the beginnings of a new outlook?

Laurence Blair

Maybe in some parts a new generation reared on anime cartoons, Hollywood movies and BTS videos on TikTok is looking to the future, and trends from Asia and the Global North, to orient their worldview.

But at least in Paraguay, where I’m based, political discourse is still filtered through the lens of the 1864-70 War of the Triple Alliance, which saw Marshal Francisco Solano López lead the country into a disastrous conflict that wiped out half the population, including López. Yet he was lionised by the 1954-89 dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner. And today, just about the worst thing you can call your opponent is a legionario: after the Paraguayan exiles that fought with Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay to overthrow the marshal.

I don’t think this obsession with the past is entirely unique to Latin America. The contemporary rise of India and China is also presented by their leaders in terms of being ancient civilisations, restored to greatness once more. In Britain, where I’m from, certain myths about 'standing alone' against Nazism during World War Two (overlooking the burdens undertaken by the Empire and the Soviet Union) have a powerful political salience to this day.

But I think there is something particular to this continent about how dead-and-gone figures like Evita and Juan Domingo Perón, Zumbi dos Palmares, Ernesto 'Che' Guevara, Túpac Amaru II, Marshal López and Hugo Chávez continue to inspire devotion and disgust in the here-and-now. Perhaps it’s related to the deep tragedies that have marked its history, and the messianic, utopian yearning for justice that results. Maybe it’s partly an inheritance from pre-Columbian cultures, whose mummified ancestors enjoyed more prominence and richer social lives than many of the living.

In South America, to take some liberties with William Faulkner, the dead are never past. They’re not even dead 𖡹

Over nearly a decade's reporting, he has broken stories about archaeological discoveries in the Atacama Desert and coup attempts in Bolivia and Paraguay; rafted down Amazonian rivers with former rebels in Colombia and flown into drug plantations with special forces; trekked over the Andes with Argentine gauchos into Chile, journeyed to remote islands off the coast of Peru, and walked with Venezuelan refugees into the lawless Darien jungle.

He studied Ancient and Modern History at the University of Oxford before moving to South America, where he is currently based out of Asunción, Paraguay.

Winner of the Bodley Head/Financial Times Essay Prize for Dreams of the Sea - his tale of a visit to Bolivia's landlocked navy - and the Royal Society of Literature's Giles St Aubyn Award, Patria: Lost Countries of South America is his first book.

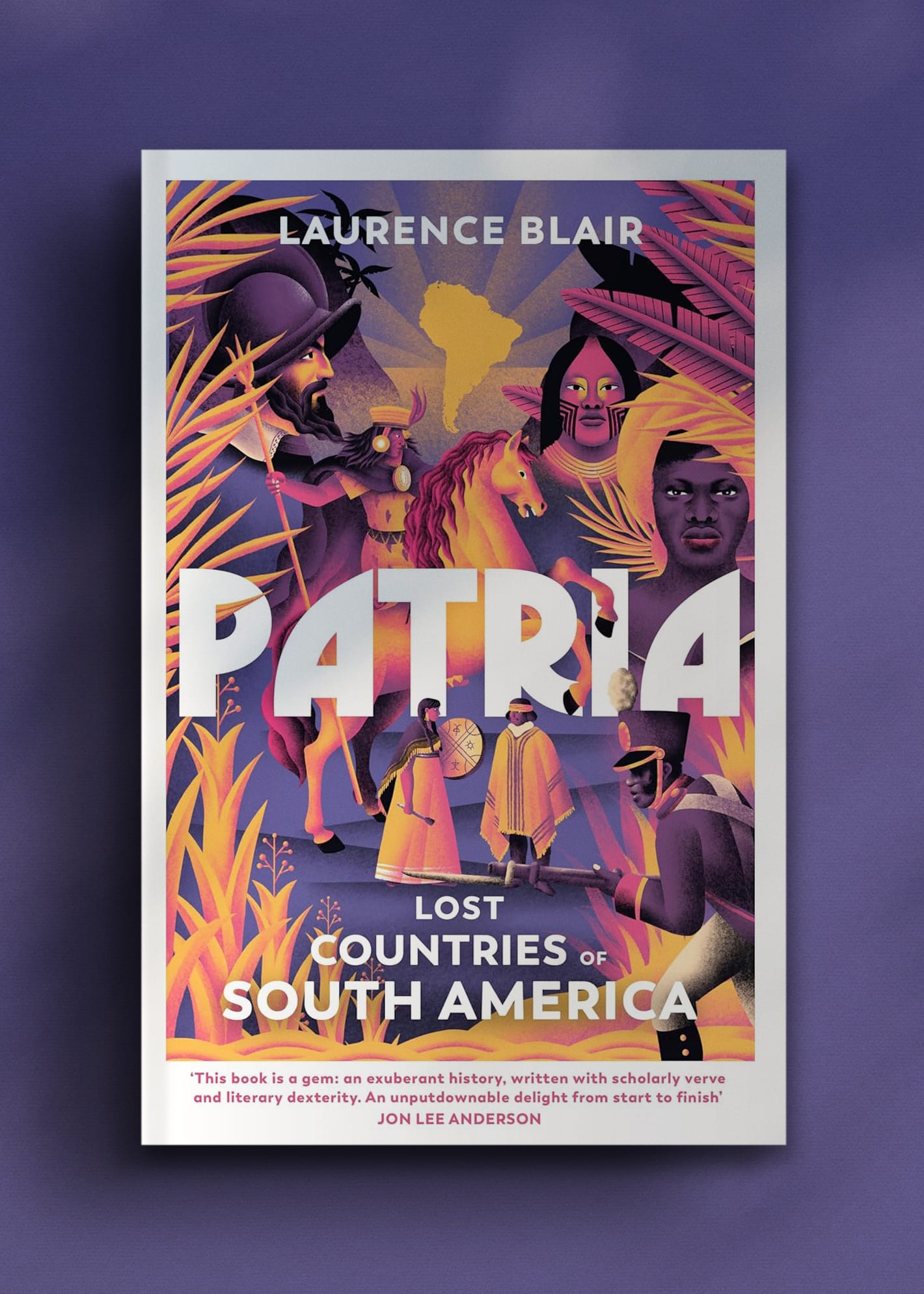

Patria: Lost Countries of South America

Bodley Head, 7 November, 2024

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1847924681

"Extraordinary … [t]his debut turns the familiar story of South America’s origins inside out"

– Alex Diggins, The Telegraph

Patria tells an alternative history of South America, spanning thousands of miles and five centuries to the present. Looking beyond modern borders, Laurence Blair takes as his waymarks nine countries that can’t be found on a map: vanished realms, half-imagined utopias and dismembered homelands.

Blair’s journey ranges from ancient Amazonian city-states and a rebel Inca dynasty in the jungle – via a Brazilian Wakanda that defied slavery, Bolivia’s landlocked navy, and the Patagonian power that defeated the Spanish – to fall in with the African freedom fighters who marched over the Andes, and the New World Napoleon who led Paraguay to its ruin.

Groundbreaking recent scholarship, striking archaeological discoveries and vivid eyewitness reporting – including encounters with drug lords, Indigenous leaders, refugees and former guerrillas – weave a story of survival, resistance and revolution, restoring South America to the centre of world history.

"A work of scholarship in its own right ... Patria also has a descriptive flair that lifts Blair’s stories off the page. Best of all, it introduces us to the myriad voices within South America that are retelling their own past"

– Oliver Balch, The Spectator

With thanks to Ben McCluskey. Author Photograph © Laura Iparraguirre