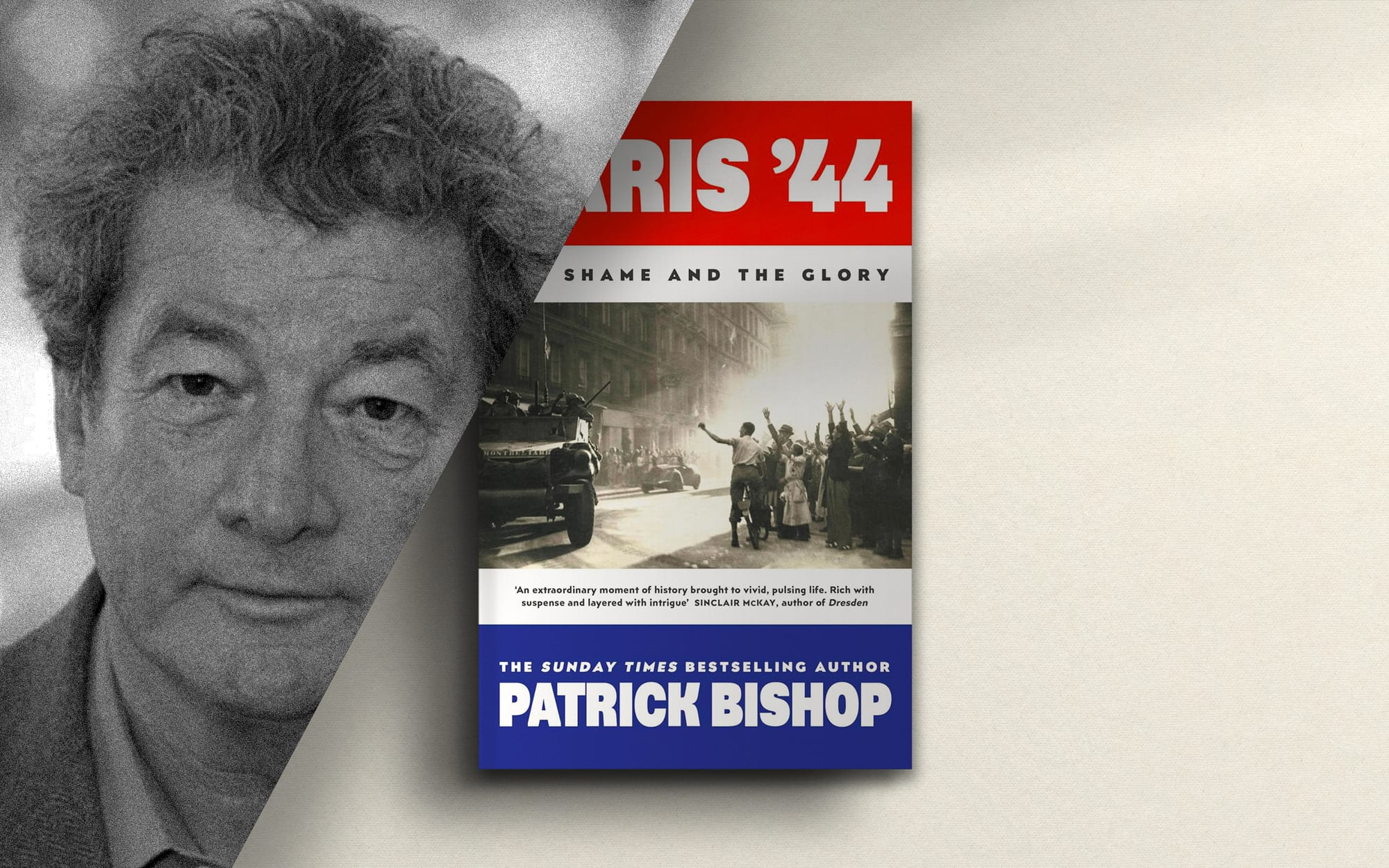

Paris '44: The Shame and the Glory with Patrick Bishop

On the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris in August 1944, we talk to Patrick Bishop about a complex episode in French history

In Paris's long, magnificent history, the years 1940-4 bookend one of its bleakest moments.

After the dramatic fall of the city in June 1940, the French capital was occupied by the Nazis who systematically looted it of its cultural treasures and drew many into acts of collaboration.

On the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, the journalist and author Patrick Bishop looks back at this fraught moment in French history.

The author of a new book on the subject, Paris '44, Bishop reflects on a story that is sharply split between shame and glory.

Unseen Histories

Your book's title, Paris ‘44, evokes the glorious moment of liberation, exactly 80 years ago, when the Nazi forces were finally driven out of the French capital. Is it fair to say that the book is almost equally about Paris ‘40, when the city fell?

Patrick Bishop

Yes. You can’t really understand Paris ’44 unless you understand Paris ‘40. And you've got to lay the foundations for all the kinds of dilemmas that [the French people] faced. The history of the occupation is obviously very germane to how events played out.

The experience of 1940 was a very shameful one for Parisians and the French, because the army just rolled over in front of Paris. Even though it had fought very hard to defend Paris not that long before, in 1914, they basically just allowed the Germans to march in. It was a very shameful moment for the army and the French people in general.

I think people, in their hearts, felt very uneasy about the ease with which the Germans had taken over. And also, the way that the new French government just became an adjunct of the Nazi state. There were a lot of troubled consciences, You have to explain all that to understand why the liberation had the sort of historical charge that it did.

Unseen Histories

As you say, there was this dramatic collapse in the spring of 1940. It only took the Germans 35 days from the beginning of their western offensive to reach Paris. How did people at the time make sense of this shocking collapse, which was such a contrast with what had happened in 1914?

Patrick Bishop

There was a lot of scapegoating going on. The right wing blamed the centrist and leftist public politicians for either provoking war with Germany, which was the far-right view or for not giving the Army the wherewithal to fight the war properly — even though they had built the Maginot Line.

It was all very contradictory, basically, because everyone felt some degree of complicity. Everyone felt a little bit guilty. I think that's the truth.

Unseen Histories

At the beginning of Paris '44 you have this great set piece scene of Hitler charging around and viewing the sites as a really bizarre, kind of tourist. Another sense of unreality came a few weeks before when you show the strange atmosphere of denial that was in the Parisian streets in May 1940 as the Nazi forces approached. Is that right?

Patrick Bishop

If you go back to 1914, it had happened before in the fairly recent past. The people assumed they [the Germans] would be stopped again at the gates of Paris. But I don’t think there’s much you could read into that. It's just one of those things that often happens. People tend to be quite insouciant, strangely enough, in the face of disaster. It is something I’ve often seen in my experiences as a war reporter.

Unseen Histories

A counterpoint to Paris in the book— Paris with its edgy politics, jazz and existentialist philosophers—is the docile, shallow town of Vichy. You write that Philippe Pétain’s new capital was almost like ‘an act of atonement for the sins of the flesh’. Do you want to say something about that?

Patrick Bishop

It is a common theme of the critics of the Third Republic that Paris was a corrupt environment where there were a lot of scandals, financial scandals mainly. There was a Catholic, reactionary spirit which was very strong in those years, exemplified by the Action Française movement. It was always going on about how we can return to ‘traditional values’. This is very much the kind of aesthetic and the theme of Vichy.

Paris was kind of a symbol of the avant-garde: the political decadence, communism, libertinism. It’s a bit of a facile point, but Vichy is where you go to take the waters and to purge yourself and so even though it was a complete fluke that they ended up in Vichy, some people saw it as a bit of a metaphor.

Unseen Histories

Your cast of characters is drawn from the familiar and the obscure. I think one good touchstone is Pablo Picasso, who remained in Paris. I was surprised when I was reading just how much, freedom he seemed to have to continue with his creative work during a period of repression. Is that correct?

Patrick Bishop

It's a very interesting subject. Picasso had shown a certain amount of courage in staying put. He could have gone anywhere. The Americans offered him asylum. His own reason was that he just was quite happy where he was. He regarded the war as a nuisance.

He was very apolitical Picasso. Despite his later membership of the Communist Party and despite painting Guernica, he was actually not a political animal. And so he himself said that staying in Paris was basically an act of kind of stubbornness or egotism where he just didn't want his rhythms to be disrupted by the war.

He wasn't allowed to exhibit in Paris because his work had been deemed degenerate in the notorious exhibition put on about degenerate art by the Germans before the war. But he was allowed to carry on painting and indeed he mixed in these salons where Germans and French intellectuals and celebrities came together.

He would attend those, not frequently but sometimes. Indeed, as I say in the book he had an acquaintanceship, at least with Ernst Jünger. the German writer who was a military officer, and so he was not averse to actually socialising to some degree with the Germans.

But the Germans really left him alone because they knew that he was a world-famous figure. Even they felt he was untouchable, in the sense of punishing him or persecuting him or doing something nasty to him. It would not do them any good.

It does seem extraordinary that people who were prepared to kill people by the millions, Jews and Slavs, would hesitate before laying hands on Picasso. But that was the reality. That was his standing in the world.

Unseen Histories

Paris has been associated with cultural splendour for so many centuries. How systematically did the Nazis loot the city of its paintings and artefacts during the period of occupation?

Patrick Bishop

In a very systematic and industrial way, masterminded really by Hermann Göring. Goering fancied himself as a great collector, or rather looter. He ordered a special team, a sort of quasi military force, to set about stealing all the best stuff.

It had two purposes. One was to add to Göring’s collection. But also there was going to be a sort of ‘Hitler Gallery’ in Austria, in Linz, where all the world's great art, all the great European art was going to be displayed. The loot was going to be diverted off there.

All this stuff that they didn't like but had commercial value, like modern art or degenerate art in their eyes, a lot of it went off to Switzerland to dealers there, who sold it. The prices they paid for it went towards this museum. That was the plan anyway. It was a very industrial scale operation.

Unseen Histories

A phrase you use is ‘a fog of moral confusion’ which surrounds the early portions of the book. One character who really rises from the pages with a very definite stance and is very strident in his writing is the journalist Robert Brasillach. Can you tell us a little about his story?

Patrick Bishop

Brasillach’s story is particularly interesting. There were quite a lot of people like Brasillach, who were intellectuals and who in the 1930s, when faced with all the confusion of the times, reached for the political extremes. A lot of people went to the left and became communists; others went to the right and became fascists.

They often came from overlapping backgrounds. You could be a bright, young intellectual like Brasillach and go to the best university establishments in Paris and half a class would become communists, the other half, (well not half but a significant number in a cohort) would go in completely different political directions.

Brasillach went off to the right. But he was a particularly egregious case because he went from being a sort of right winger to being a thoroughgoing collaborationist.

And he wasn’t even the most extreme. There were people who worked for his newspaper, Je suis partout, who were more Nazi than the Nazis.

But Brasillach is an interesting case. I think he would fit in quite well today. He was a narcissist who was constantly seeking attention. And, as the Germans gave him a lot of approval and flattered him, he was quite happy to go along with them.

He was also a typical French intellectual in the sense that he believed in power of words and argument: that intellectual fireworks kind of justified almost anything.

When a lot of these collaborators bolted as the Allies advanced [in the summer of 1944] he stayed put in Paris. He was so sure of his intellectual powers that he thought that he would be able to answer all the charges against him in a convincing fashion in a court of law.

He failed to do this and was put to death, shot as an example. There was so many of these intellectual collaborators. Someone had to suffer in the purge, or rather in the limited purge, that followed the liberation.

And it was his misfortune, or his stupidity in hanging around, that he was the one. De Gaulle was petitioned to spare his life—to commute the death sentences to imprisonment—but he though ‘no, someone’s got to pay the price’ and so it was Brasillach.

Unseen Histories

The summer of 1941 seems to be an inflection point in the story. It was then, after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, that there was a sharp increase in the number of heroic acts of resistance from many very young working class men. You tell a series of these stories in the book. Do any of them remain vivid to you today?

Patrick Bishop

There's a lot of heroism in the communist role in all this. Yes, it is shameful that they were told not to do anything during the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact. That sat very uneasily with a lot of the rank and file. But when they got the orders to start attacking the Germans they did so with gusto.

What you have to remember is that even though these are communists, they are very, very patriotic, French men and women at the same time. They are reinforced by all these noble figures, a lot of Jewish, people who've been forced out of all the Nazi territories, really, even before the war. You get a lot of kind of working class Jewish Parisians of Polish origin or German origin, and who are very present in the French, communist movement.

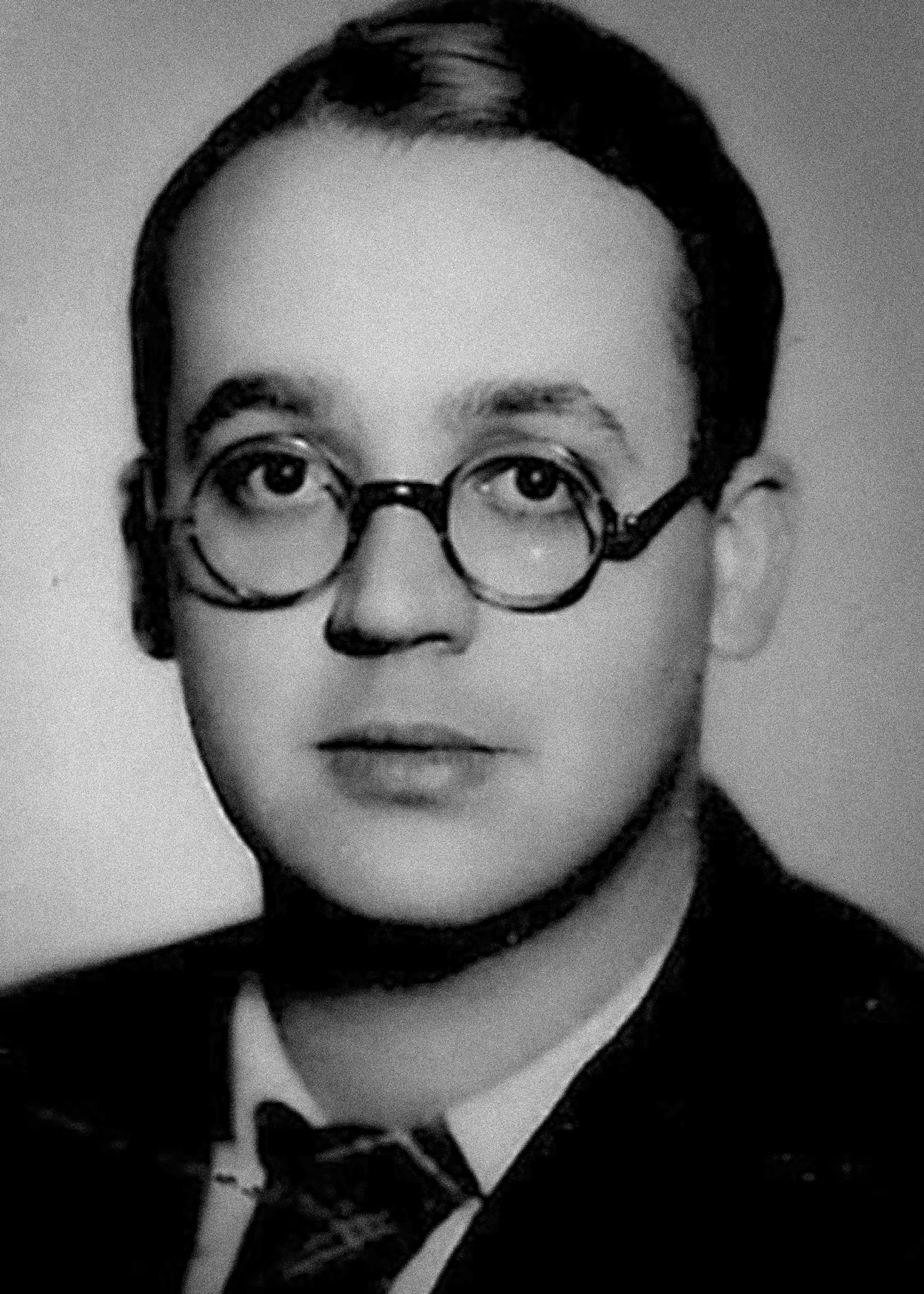

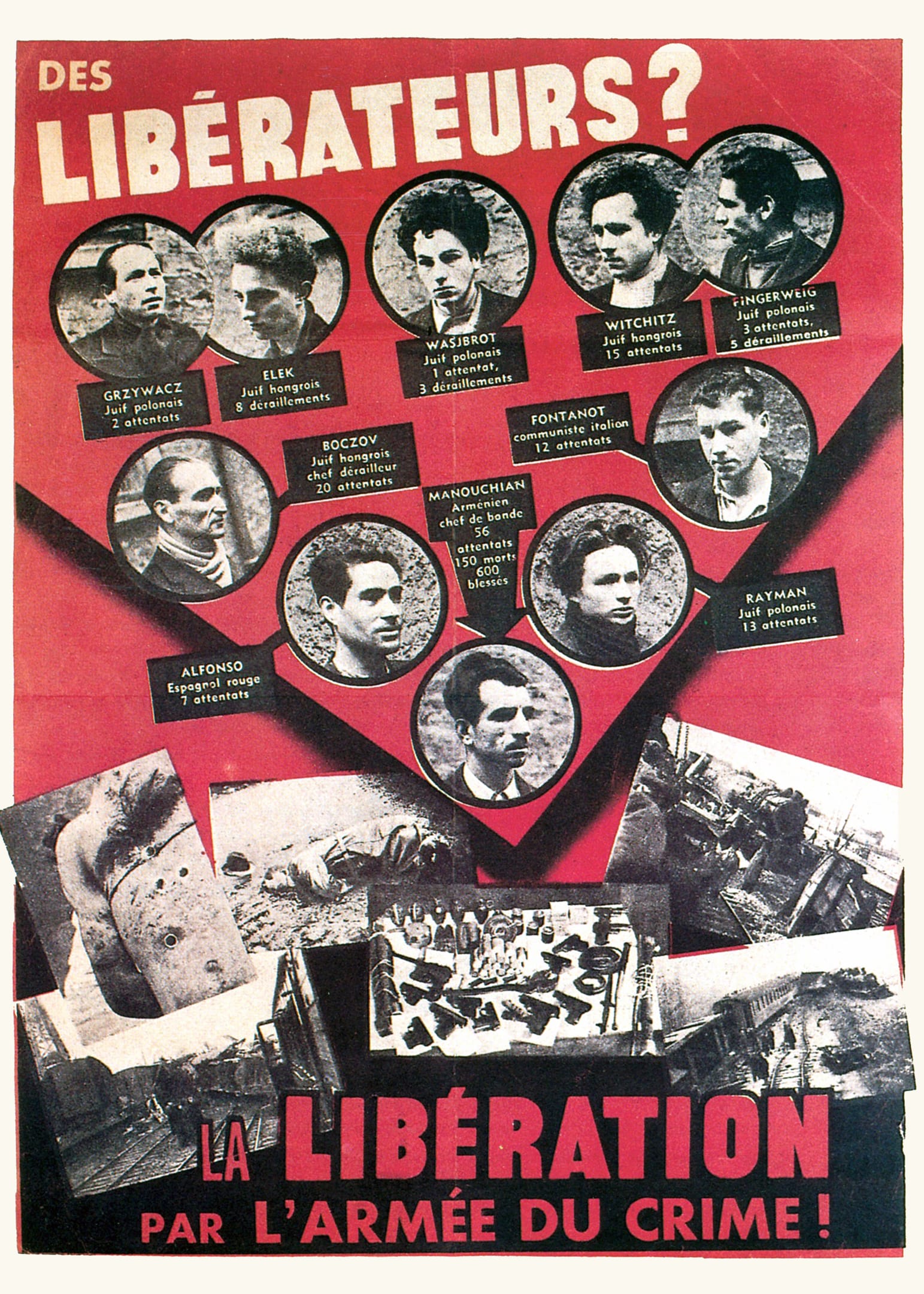

One of the stories that I find particularly moving is that of the Manouchian group, led by this very charismatic Armenian, Missak Manouchian who was a poet. His parents were killed in the Turkish genocide and he was brought up in Lebanon where they spoke French in an orphanage there. Then he came to Paris and worked in the automotive industry, which is where a lot of communists were found.

He then was part of this group, the FTP, who were really effective. They were betrayed, rounded up and shot but a poster that the Germans put up, presenting them as terrorists had exactly the opposite effect on the general population. It ridiculed their claim to be freedom fighters: But in fact, the 'red poster' as it became known as it was printed in blood red ink had the opposite effect. It’s very, very striking. You see these raggedy, wild haired young men, glowing with defiance just before they were shot. They are staring death in the face and they look very proud. It brings tears to my eyes when I look at it.

Unseen Histories

One final question. De Gaulle is obviously a great protagonist in the story. He's mostly off stage across the Channel in London, but it is he who goes on to fix the account of the liberation most strongly in the popular imagination. How much of de Gaulle's version tallied with what you found out during your research?

Patrick Bishop

Well, it is a fiction. The speech de Gaulle made on arrival in Paris at the Hotel de Ville, he claimed later to have made up on the spur of the moment. He hadn’t. He had very carefully crafted it, because it's the foundation of the myth that Paris had liberated itself. This was a great moment in French history that they could take pride in.

But if you actually look at what he says, it's all basic fabrication. You know, he says in the speech, he says he starts off by saying Paris has been outraged. It has been broken. It has been martyred. But now it's liberated. Liberated by itself. Liberated by the armies of France. Liberated with the help of the whole of France. For the France that fights. The France that never surrenders.

Almost every one of those statements is untrue. French troops were the first into the capital. But that was only because Eisenhower allowed them to do that. All their equipment was American. And the uniforms? they were American. They were backed up by the American Fourth Division. France itself had never as a whole played any part in this event. And this France that fights? Well actually that image was very much tarnished by the experience in 1940 where they hadn’t fought at all, certainly in terms of protecting Paris.

But de Gaulle knew that had this opportunity to create a myth. Myths are very, very powerful. People don’t examine the actual claim that closely as we’re finding today in the age of lies and deliberate disinformation. So, you know, you could actually frame this as positive disinformation if you like.

So, yes, it doesn't bear up. It doesn't bear close examination. Having said that, you know, I’m not playing down the sacrifices that were made in the uprising. A lot of young men and women died, and quite a few of the middle aged category, and they laid down their lives to actually restore some honour to France. We shouldn't ever underestimate that courage or such heroism 𖡹

He spent twenty-five years as a foreign correspondent covering conflicts around the world and he is the former Paris bureau chief of the Daily Telegraph.

Paris '44: The Shame and the Glory

Viking, 25 July, 2024

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0241492963

From the Sunday Times-bestselling Patrick Bishop comes a heart-stopping countdown narrative recreating the liberation of Paris in 1944, one of the great and most dramatic hinge moments of WW2.

When the Germans marched in and the lamps went out in the City of Light the millions who loved Paris mourned. Liberation, four years later, triggered an explosion of joy and relief. It was the party of the century and everybody who was anybody was there. General Charles de Gaulle seized the moment to create an instant legend that would take its place alongside the great moments in French history. After years of oppression and humiliation Parisians had risen to reclaim their city and drive out the forces of darkness – or so the story went.

This fresh new account of the liberation, packed with revelation, tells the story of those heady days of suspense, danger, exhilaration – and vengeance – through the eyes of a range of participants, reflecting all sides of the conflict: Americans, French and Germans; resisters and collaborators. Among them are famous names like Ernest Hemingway, J.D. Salinger and Pablo Picasso, but also some fascinating unknowns including a medic turned Resistance gunwoman, an androgynous Hungarian sculptor and a French bluestocking who quietly set about saving the nation’s art treasures from the Nazi looters.

Paris ’44 looks behind the mythology to tell the real story of the liberation and expose the conflicts and contradictions of France under the occupation – the shame as well as the glory. This gripping war-time narrative will enthral anyone who has a place for Paris in their hearts.

"Paris ’44 tells the story of the occupation and the liberation, but it does not read like military history . . . The book resembles some epic thriller, with vividly evoked characters all somewhere on the spectrum between collaboration and resistance, shame and glory . . . Paris ’44 is a wonderful book: droll, moving, with a cinematic eye and not a boring line in it"

– Andrew Martin, Observer

"An evocative account of the city’s liberation . . . Bishop is such a skilful writer, with a sense of nuance and an eye for memorable anecdotes, that even readers familiar with the story will enjoy his book enormously . . . history, like life, is complicated, and Bishop’s admirable book treats it with the respect and care it deserves"

– Dominic Sandbrook, Sunday Times

With thanks to Annabel Merullo