Magnificent Power: the monuments of Ancient Rome with Paul Roberts

Paul Roberts tells us all about his revealing new history of the Eternal City

Few places on Earth can rival Rome for monuments. Dotted across the heart of the ancient city are old temples and statues; the ruins of old debating chambers and theatres.

Paul Roberts's relationship with these evocative buildings began on a family holiday in 1976, when he saw the Colosseum for the very first time.

Now Roberts has written an inventive history of Rome, told through fifty of its most telling buildings and monuments. In this interview he tells us more about a project that has been almost fifty years in the making.

Unseen Histories

Ancient Rome in Fifty Monuments is a beautifully illustrated and very erudite guide to the city. Can you tell us about your own first visit to Rome and if any of its buildings made an impression on you at that time?

Paul Roberts

I vividly remember my first visit to Rome on a family holiday in 1976. The first afternoon we took a taxi to the Colosseum and the driver dropped us at the north, full-height side. We got out of the taxi looked up and went rigid! Mum used to tell me how my jaw just dropped and I stood there for quite a while.

I was completely transfixed, taking in the sheer scale and remembering all I’d read about the emperors who built it and the gladiators that fought in it. I think it’s had the same effect on people all through time!

Unseen Histories

Your book spans more than a millennium, beginning in the early days of Rome in around 600 BC. Can you tell us about some of the very oldest buildings that date to this time?

Paul Roberts

By about 600 BC Rome, ruled by kings not emperors, was a recognisable city with public and private buildings.

A group of temples near the church of Sant’Omobono date to around this time. But only 50 years later Rome had an established Forum area with temples and administrative buildings, it also boasted a fine set of city walls, drainage systems, an early Circus Maximus and the foundations were about to be laid for the massive Temple of Jupiter.

Parts of these – or their later incarnations – can still be seen today.

Unseen Histories

As the centuries passed, Rome grew vastly in size, wealth and splendour. It seems that there is an increasing preoccupation with the projection of power too. Is this correct and can tourists trace this for themselves today?

Paul Roberts

Building great monuments had always been a political statement – as far back as the Etruscan Kings building the great Temple of Jupiter.

Monument comes from the word monere (to remind) and when an emperor erected a building, he was giving the people something useful, giving the city something beautiful and giving his own reputation a great boost. Just to make sure large inscriptions shouted out the emperor’s name!

In putting up a building he showed the people his care for them, his wealth in affording the construction and materials costs and his power in bringing it all together in the heart of the capital. Power shifts of course and sometimes this was reflected in buildings, or in their names.

Nero’s Golden House didn’t long outlive its creator – his memory was too toxic – and the long narrow Imperial Forum of Nerva wasn’t built by him at all but by his predecessor Domitian, whose Senate-sanctioned public disgrace meant his name was not given to it.

Unseen Histories

The book is organised chronologically and it is also divided by the reigns of emperors like Augustus or Domitian. Were any of these figures particularly obsessed with the architecture of the city or did it generally grow organically?

Paul Roberts

Parts of Rome grew very organically – for example the main Forum Romanum – but there were periods or events, in particular fires, which allowed Emperors the opportunity to shape or reshape areas of the city.

Augustus, who said he’s found Rome 'made of brick and left it made of marble', overhauled the Forum and the Campus Martius in the city’s centre and north west, but often rebuilding existing monuments.

Nero profited from Rome’s great fire in the 60s AD to build his new and massive palace or Domus Aurea: the Golden House. Julius Caesar and after him several Emperors laid out new Imperial Forums, hugely destructive of earlier structures. So there was no set approach.

Unseen Histories

Perhaps the most dramatic period of Roman history occurred in the first century BC, with the victories of Pompey, the coming of Caesar and the oratorical brilliance of Cicero. Which of the buildings connect us most powerfully to this fascinating era?

Paul Roberts

Caesar and Pompey wrestled for control of the Roman Republic on the battlefield, in the Senate House and on building sites! Public works were such important, and such visible propaganda.

One of the most significant buildings for this swan song period of the Roman Republic is the great Theatre of Pompey and its huge porticoed square. Nothing of it remains above ground but, fascinatingly, the theatre’s outline can be traced from above by following street patterns in the Campus Martius area of the city.

Pompey’s theatre was very grand and prestigious. It was the first fixed theatre to be built in the city. Fixed theatres had previously been banned by the Senate as unRoman, even immoral, but Pompey’s was allowed because he built a Temple of Venus on the top of it and claimed the complex was religious!

Caesar had to respond and planned several major building projects, including a new Senate building in the Forum Romanum a whole new Forum, and his own theatre, planned (of course) to be even greater than Pompey’s.

The new Forum remained substantially under construction in his lifetime. But far from bringing him glory, events around its Temple of Venus (Caesar’s legendary ancestor) may have stoked the concerns over his perceived sense of self-importance, and possible desire for kingship, that led to his assassination.

Unseen Histories

The Colosseum (or, more properly, Amphitheatrum Flavium) is the building that continues to act as an emblem of the city to this day. Did anything like it exist before it was constructed or was it a quite unique structure?

Paul Roberts

Other arenas were built in Rome and Italy before the Colosseum. Interestingly the oldest surviving arena, dating to around 70 BC, is in Pompeii.

In Rome there were at least two arenas before the Colosseum. One built by Augustus in around 29BC that was destroyed in Nero’s Great Fire in AD 64. The earliest recorded arena in Rome – and the most ingenious – was constructed in 52 BC by an ally of Julius Caesar's: Gaius Scribonius Curio.

This was made of wood and comprised double (in Greek ‘amphi’) semicircular theatres which during the morning showed standard theatrical performances. In the afternoon they swivelled together to form an ‘amphitheatre’ for gladiator combats.

Pliny comments, disapprovingly, that the crowd didn’t bother (in those pre-health and safety days) to clear the theatres before they were manoeuvred together!

Unseen Histories

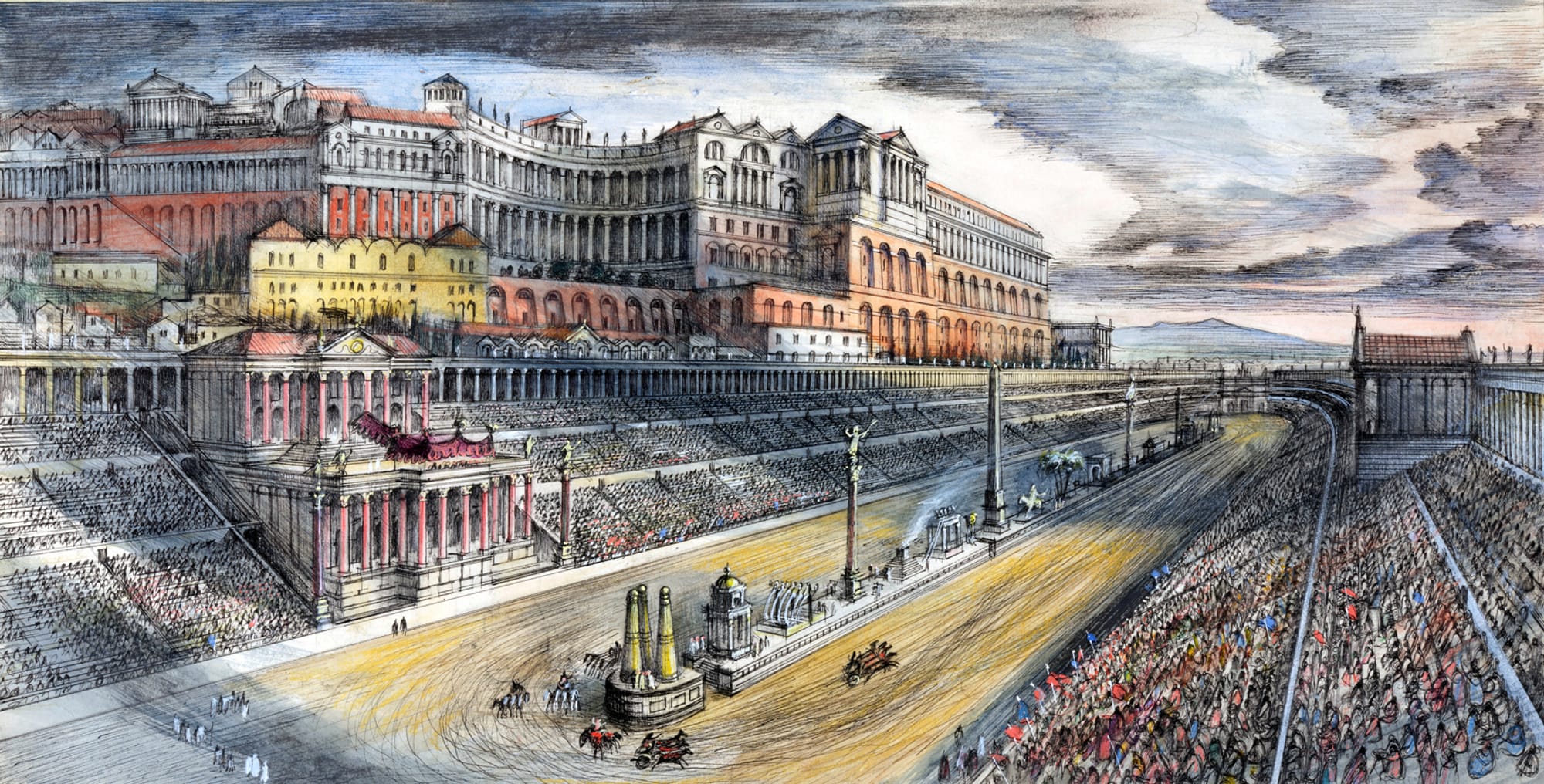

Despite the Colosseum’s enduring appeal, you point out that the Circus Maximum was actually ‘the largest structure for spectacular entertainment in the ancient world’.

Your book includes a fabulous double page illustration of a chariot race taking place inside it. Can you tell us a little about its particular history?

Paul Roberts

The Circus Maximus goes right back in legend to Rome’s first king, Romulus, who used the invitation to the neighbouring Sabine people to watch racing in the Circus as a pretext to kidnap their women.

In reality races were certainly held on the site of the Circus from very early in Rome’s history. And not only races. Beast fights, and on occasion executions and gladiator combats were held here. Successive rulers from Juius Caesar to the Emperor Trajan embellished it.

Caesar put in a great ditch to stop beasts from escaping and reaching the crowd and rebuilt some of the mostly wooden Circus in stone to try to prevent fire. The fact that Nero’s great fire started here shows he didn’t quite succeed. The Emperor Trajan finished the job and most of the seats (30 km worth!) and all of the colossal superstructure were replaced in stone.

Unseen Histories

The Romans were clearly interested in scale and they made great use of expensive materials like marble. Did they utilise height in their buildings, too, to project a sense of power?

Paul Roberts

Yes, they certainly did. There was the staggering height of the outside of monuments such as the theatres, the Temple of Jupiter and the Colosseum (that so affected me). But there was also the impact of height inside monuments – the soaring ceilings of the great basilicas – the billowing vaults of the massive imperial baths. These were the highest and largest ceilings ever constructed until the Medieval cathedrals.

Then there were monumental columns – simple ones supporting statues and then the ornate, story-telling columns – which we can still admire today such as Trajan’s Column.

Even in those days it was a tourist sight. A spiral staircase inside Trajan’s Column leads to a viewing platform giving views over the heart of Rome!

Unseen Histories

We read frequently about the astonishing archaeological finds in Pompeii. Is there an equal amount going on in Rome at the moment, and, if so, has it taught us anything new about these very old buildings?

Paul Roberts

There is an awful lot going on in Rome. This is both through re-examination of the existing remains – a greater analysis of building materials and structural techniques – and also new discoveries.

These usually arise from construction work for new buildings or transport like Rome’s Metro Line 3.

They allow us to identify structures, known through literature but considered lost, such as Hadrian’s auditoria for cultural and literary events found slap bang in the middle of Rome’s Piazza Venezia.

There are also the remains of a small but beautifully decorated theatre near the Vatican in which it’s likely the Emperor Nero practised his preforming ‘skills’! 𖡹

He has curated numerous popular exhibitions, including ‘Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum’ at the British Museum in 2013 and ‘Last Supper in Pompeii’ at the Ashmolean in 2019–20. Roberts wrote the accompanying exhibition catalogues to both.

A trained archaeologist, Paul has been involved in various fieldwork projects across Italy and Greece.

Ancient Rome in Fifty Monuments

Thames and Hudson, 18 April, 2024

RRP: £30 | ISBN: 978-0500025680

A sweeping new history of the city of Rome, told through its emperors and the monuments they built to make their mark on one of the great capitals of the classical world.

‘What is worse than Nero? What is better than Nero’s Baths?’ – so wrote the poet Martial in the first century AD, demonstrating the power that buildings have on public consciousness. In ancient Rome, who built a monument and why mattered as much as its physical structure. Over centuries and under many different emperors, a small village in Italy was transformed into the crowning glory of an empire. Seeking out the personalities behind the great building projects is key to understanding them.

With this firmly in mind, Paul Roberts takes the reader on a tour of ancient Rome, vividly evoking the sights and sounds of the city: from the roar of the crowds at the Circus Maximus and the Colosseum, to the dazzling gleam of the marble- and mosaic-covered baths of Caracalla and Diocletian. He tells this story emperor by emperor, drawing out the political, social and cultural backdrop to the monuments and ultimately the very human motivations that gave rise to their construction – and destruction. These fascinating buildings are further brought to life with reconstructions that show how the ancients themselves would have experienced them.

When and why were these monuments built? What did they add to the lives of the people who used them? What impact did they have on the shape of the city? Roberts expertly weaves together the latest archaeological research with social and cultural history, to tell the story of the Eternal City, always in some way rising, falling and being rebuilt.

"Details the monumental constructions of ancient Rome, with a particular focus on the impact of the city's leaders on its built environment... A chronological political history follows the rulers who built each monument and includes some discussion on both the methods and the rationales for their construction... Solid, recommended, [and] visually rich."

– Library Journal

With thanks to Caitlin Kirkman