Philip Augustus, Medieval England’s Greatest Enemy

Catherine Hanley considers the legacy of a brilliant leader

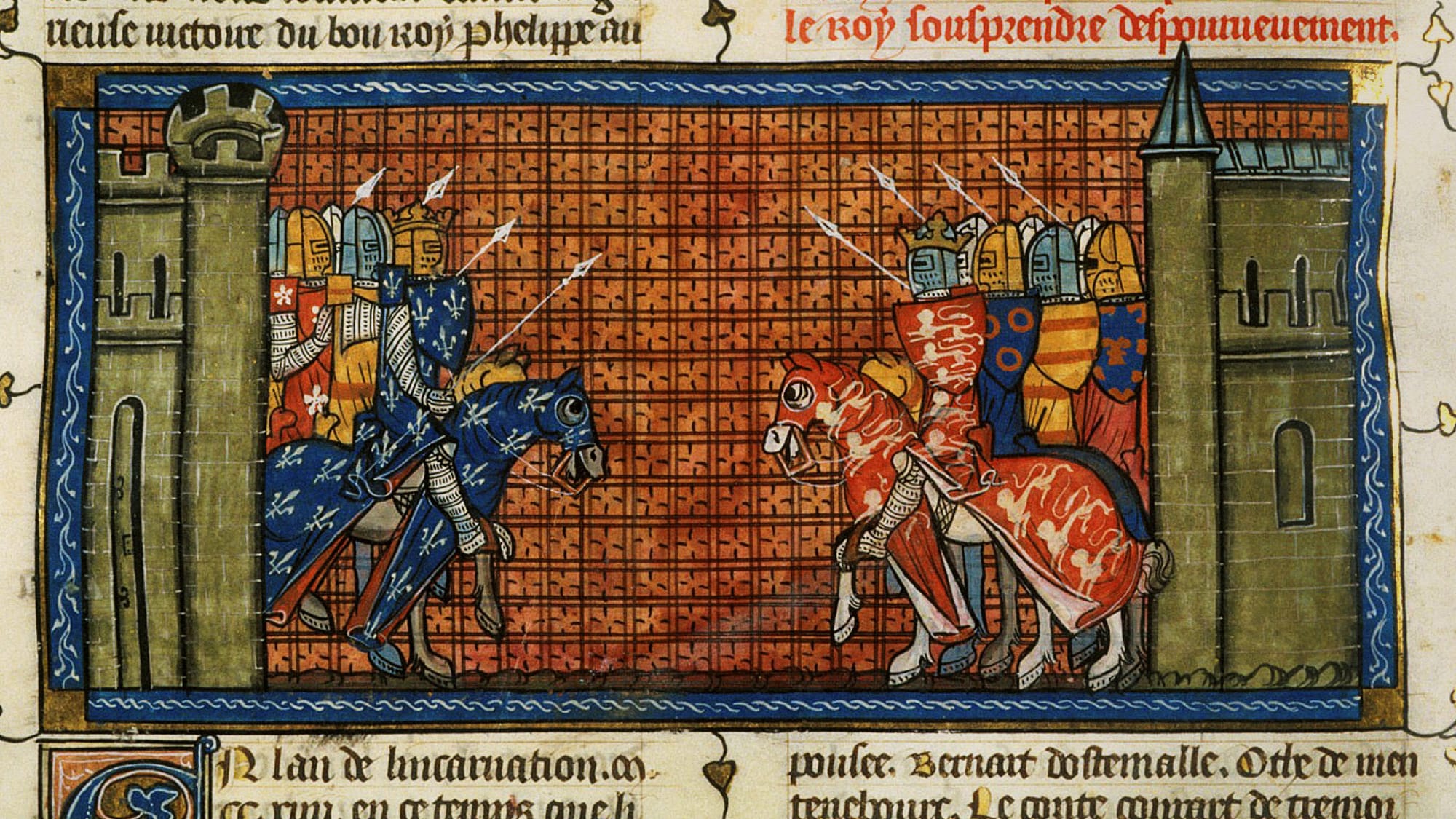

When Philip II, or 'Philip Augustus', ascended to the French throne, many challenges at home and abroad confronted him.

At this time the King of England, Henry II, actually ruled more of France than he did. But an inspired series of political moves followed and very soon the balance of power began to tip.

Here Catherine Hanley, the author of Nemesis, encourages us to learn more about a critical figure in Medieval history.

When we read about the early Plantagenet kings of England – Henry II and his sons – we often hear that their arch-foe was Philip, the ruler of France. But not much is known about him in England: who was he, and how did he manage to knock the Plantagenets off their perch, one by one?

Philip II, more commonly known as Philip Augustus, was crowned as the ‘junior’ king of France in November 1179, during the lifetime of his father Louis VII. He was just 14 years old at the time, and he was obliged to take the reins of government into his own hands straight away due to Louis’s poor health. He became sole king upon Louis’s death less than a year later.

With the ruler of France a mere boy, it was not long before ambitious vassals and foreign adversaries began to lick their lips. But it turned out that the young Philip was possessed of a sharp political acumen, plenty of martial skill and energy, and a single-minded, ruthless determination to do whatever was best for France.

Almost immediately after his coronation Philip set about subduing his rebellious domestic lords, cultivating a divide-and-conquer technique that he would hone to perfection in later years against the Plantagenets.

He skilfully played the two most powerful factions of Champagne–Blois and Flanders–Hainaut off against each other via a two-stage marriage game. First he insulted the former and favoured the latter by marrying Isabelle, daughter of the count of Hainaut, even though she was betrothed to the son of the count of Champagne; then he reversed his position and threatened to divorce her unless her father and her uncle of Flanders came to heel.

His stratagems paid off, and within five years of his coronation the four influential counties of Champagne, Blois, Flanders and Hainaut had all submitted to him. France was more united than it had ever been, and Philip had demonstrated that a shrewd and foresighted king did not necessarily have to draw his sword in order to achieve his political aims.

He was now free to turn his attention to an even greater foe.

At this time Philip’s opposite number on the throne of England was Henry II, a formidable figure who, thanks to his additional holdings in Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine, actually ruled more of France than Philip did.

Henry was vastly more experienced than Philip, having worn the English crown for more than a quarter of a century. He had four sons: Henry, known as the Young King; Richard the Lionheart; Geoffrey, duke of Brittany; and John, then known as Lackland.

The first three of these were grown men older than Philip. They were well trained for future leadership roles but the French king refused to be intimidated.

Philip recognised that the best way to start undermining Henry’s power was to use his sons against him. He courted them one after the other, identifying their individual weaknesses and using them to best effect. His general strategy was to play off whomever was the head of the family against his heir and nearest rival, and in this he was spectacularly successful.

To begin with Philip encouraged Henry the Young King and Geoffrey to rebel against Henry II, and after their deaths (in 1183 and 1186 respectively) he switched his attention to the new heir, Richard, causing a fresh rift by whispering in his ear that it was highly suspicious that Henry II would not publicly name his eldest surviving son as his successor.

After Henry II’s own death and Richard’s accession to the throne, in 1189, Philip smoothly repositioned once more, aiding and abetting the young John in his rebellions against his brother. Then, when Richard himself died only ten years into his reign, Philip played a pivotal role in stirring the conflict over the English crown between John and his nephew Arthur of Brittany (son and heir of the late Geoffrey).

Even after John succeeded and had Arthur murdered, Philip was not finished. There might not be any further junior members of the Plantagenet family to play off against each other, but he was happy to take advantage of John’s incompetence by conquering Normandy piece by piece between 1202 and 1204, severing the duchy’s long-standing link with the English crown and adding it to his own royal domain. The newly united and enlarged France was a major player on the international stage.

The final blow fell in 1214, when John made alliances with the Holy Roman Emperor and the counts of Boulogne and Flanders in order to attack Philip from multiple directions. Philip won a glorious victory against the coalition at the Battle of Bouvines, while John himself was simultaneously seen off by Philip’s adult son and heir (the future Louis VIII) at La-Roche-aux-Moines.

For the remainder of his life Philip reigned supreme in France and was the pre-eminent monarch in all of western Europe. Every single one of his strategies had paid off – and, indeed, if John had not died unexpectedly in 1216, leaving as his heir an innocent child whom Philip was reluctant to attack, the crown of England itself might have fallen into Capetian hands.

The final decade of Philip’s reign was a golden one. With his foreign enemies crushed and his domestic vassals compliant, he was able to become a benevolent father-figure to his subjects, many of whom could, after forty years, remember no other king.

‘The whole kingdom enjoyed peace,’ wrote a contemporary French chronicler, ‘which was very agreeable to the people. The king governed his kingdom and his people with a paternal affection, caring for all of them and beloved by all.’ The people of France could feel a strong pride in their king and in a kingdom that was now a real nation.

The history of France would have been very different without Philip Augustus’s contribution to it. He inherited a small kingdom that was in a precarious position, with over-mighty vassals jostling for power and the looming threat of Henry II and his family casting a forbidding shadow.

Philip not only survived this, but thrived and improved his position with every year that passed, demonstrating an immense talent for politics as well as no small degree of martial skill.

In so doing, Philip also had a huge influence on the course of English history. How much longer might Henry II have lived, if Philip had not encouraged his sons to rebel against him, forcing the English king to remain in the saddle without rest or respite for years on end? How much more might the Plantagenet sons have achieved, if Philip had not set them all against each other?

His constant ploy of knowing exactly which sore spot to press, which aspect of each Plantagenet’s psyche to attack, was astonishingly successful. The suspicions of Henry II against his sons and the jealousies of those sons among themselves were all fruitfully exploited, to their detriment.

In the traditional historical narrative, Philip has suffered in comparison with the glamorous and attention-hogging family of Henry II. In fact, he was objectively more successful than any of them. His story deserves to be more widely known •

This feature was originally published October 1, 2025.

Nemesis: Medieval England's Greatest Enemy

Osprey, 11 September, 2025

RRP: £25 | 272 pages | ISBN: 978-1472867445

The extraordinary tale of Philip Augustus, one of medieval Europe's greatest monarchs, and the part he played in the downfall of four Plantagenet kings of England.

Philip II ruled France with an iron fist for over 40 years, expanding its borders and increasing its power. For his entire reign his counterpart on the English throne was a member of the Plantagenet dynasty, and Philip took on them all: Henry II, Richard the Lionheart, John and Henry III. And yet we know so little about medieval England's greatest enemy.

Historian Catherine Hanley, author of the critically acclaimed 1217, redresses this imbalance, bringing Philip out of the shadows in this fascinating new history. Delving into French medieval archives, Nemesis explores Philip's motives for attacking England and in doing so we learn not only about him but discover so much more about England's most colourful and controversial of rulers - the Plantagenets.

When Philip first succeeded to the throne in 1180, Henry II of England, thanks to his Angevin and Norman ancestry as well as his wife's inheritance of Aquitaine, ruled more of France than Philip himself. By the end of Philip's reign in 1223, the pendulum of power had swung the other way. Nemesis reveals how Philip exploited the constant familiar squabbles of the Plantagenets to secure his grip on France, his wily political manoeuvring combined with a mastery of the medieval battlefield turning France into a powerhouse of Europe.

“This book is long overdue, and is a compelling portrait of Philip Augustus. Dr Catherine Hanley writes with great subtlety, clarity and precision, capturing the essence of Philip's kingship in an engaging, dynamic and well-paced narrative. A must-read”

– Caroline Burt, co-author of Arise, England: Six Kings and the Making of the English State

With thanks to Elle Chilvers.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store