The Royal Navy's Campaign to Suppress the Slave Trade with Stephen Taylor

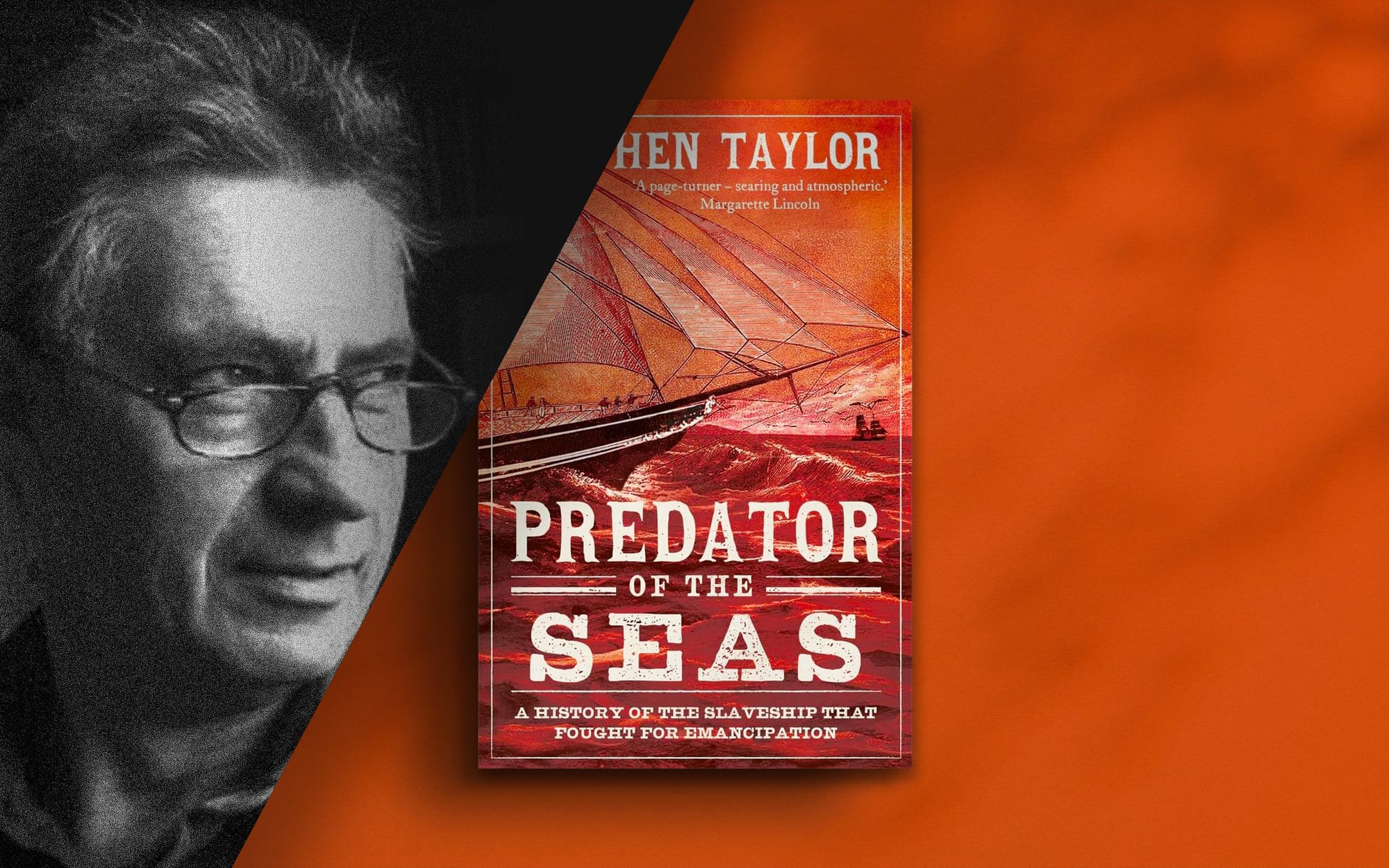

Stephen Taylor's book, Predator of the Seas, follows the life of an extraordinary vessel

Shortly after the passing of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron was formed. The purpose of this new unit was a unique one in global history. Its ships were to seize vessels that were carrying slaves across the Atlantic Ocean.

The West Africa, or 'Preventative Squadron', would remain operational over the next six decades. While estimates of the squadron's effectiveness vary, it succeeded in rescuing something about 160,000 Africans from the hands of trans-Atlantic slavers.

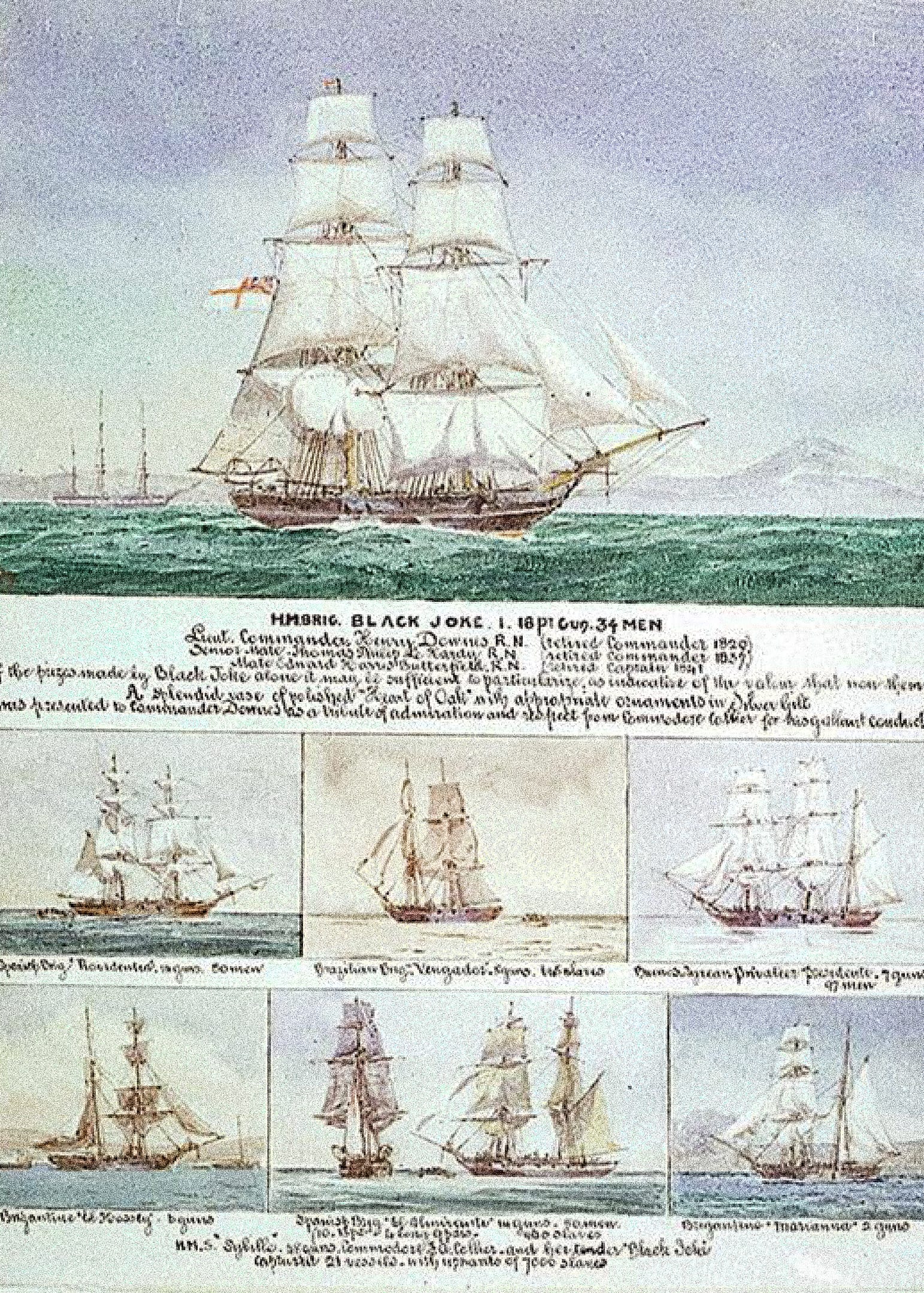

The most notable vessel in the squadron's history was HMS Black Joke. A fast-sailing Baltimore clipper, Black Joke was a curious vessel that gained glory for a series of remarkable exploits.

But there was more to Black Joke than this. Stephen Taylor, the author of a new history of the clipper, Predator of the Seas, tells us more about her contentious life.

Unseen Histories

Can you tell us where the idea for Predator of the Seas came from?

Stephen Taylor

Wartime heroics dominate much naval historiography, so I was intrigued while researching a book about the common seaman to alight upon a more complex subject, the campaign to suppress transatlantic slavery.

It was because of this complexity that I decided to focus on a single vessel – a slaver that delivered more than 3,000 Africans into the hands of her Brazilian owner before she was captured and set to rescue an even greater number from the same fate.

Telling the story became a metaphor for the paradoxes of humanity. The Henriqueta was a Baltimore clipper – fast-sailing, highly manoeuvrable and seen by seafarers as an object of exquisite beauty. Yet she was destined to inflict suffering.

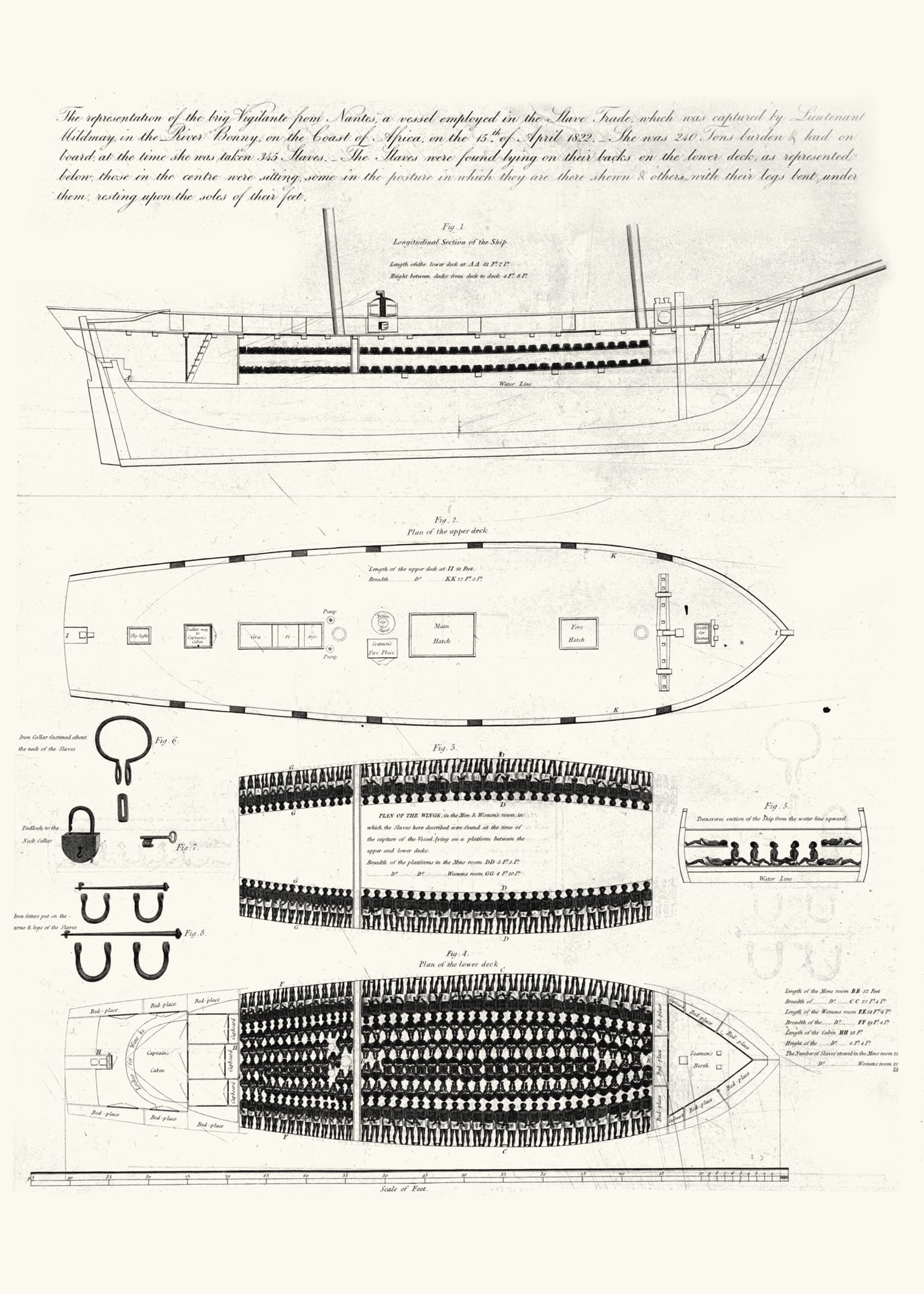

The harrowing conditions in which each of her voyages transported more than 500 African men, women and children – all within a space just 90ft in length and 26ft in breadth – challenge the imagination and defy description.

It would have been simplistic to treat the Henriqueta’s capture and use by the Navy as the Black Joke – the poacher turned gamekeeper – as a straightforward metamorphosis from evil, from slaver to saviour.

The naval campaign to stop the slave trade was a noble endeavour flawed by its execution. And those assigned to the squadron suffered their own travails. Patrolling the Bights of West Africa in this largely forgotten campaign was far more dangerous than naval battle.

A yellow fever outbreak in 1829 claimed the lives of 202 out of 792 officers and men – more than a quarter of the force.

Unseen Histories

Your story is mostly set in the 1820s, a decade caught in the interlude between the Slave Trade Act 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Was the West Africa Squadron a unique force at this time?

Stephen Taylor

Although Navy ships had cruised the Atlantic in pursuit of slavers from 1807, war with France remained the priority. Only in 1819 was the West Africa Squadron established with a permanent station at Sierra Leone.

The US, France, Portugal and Spain then adopted co-operative diplomatic positions towards ending the trade. But national priorities took precedence. Slavers from all four states continued to sail widely and the French and Americans were exempted from capture by treaties. By the mid-1820s, the 'Preventative Squadron', as it was also known, was alone in battling the slave trade.

Unseen Histories

Despite the successes of the Abolition movement in Westminster, more slaves than ever were being transported across the Atlantic at this time. Is this true?

Stephen Taylor

There are no absolute figures for the slave trade, only estimates. We may also note that prior to the Act of Abolition British ships had carried an estimated 2.6 million Africans into slavery.

But, yes, trade by Spanish slavers to Cuba surged from 1815. Meanwhile, Brazil, already a major importer of captive humans while a Portuguese colony, declared independence in 1823 and used its own unfettered freedom to enslave more Africans than any other country. That figure is put at 4.65 million.

Unseen Histories

You explain that one of the Henriqueta’s chief attributes was speed. But other strategies were deployed by slavers to frustrate the Royal Navy’s ships. Can you tell us about some of them?

Stephen Taylor

Traders were pitiless in exploiting constraints imposed on the squadron by treaty. For one, no slaver could be taken without captives on board. In the worst cases that led to men, women and children being cast into the sea as a Navy ship approached. Slavers loading in port might do the same or quickly send their human cargo ashore. In both instances, they escaped with impunity.

Under a further restriction, no slaver could be captured once it had crossed south of the Equator. With the campaign focused on ports of the Bights (Benin and Biafra) that meant the swifter, nimbler slaving brigs had only 250 miles or so to run before they were exempt. From that point the humans below faced only death at sea – of which the prospects were high – or enslavement.

Unseen Histories

What documents survive that have helped you to reconstruct life aboard the Henriqueta?

Stephen Taylor

Specific records are incomplete, due to the destruction in Brazil in 1891 of those relating to the country’s slave trade. Valuable sources survive among the papers of captured slavers taken to Freetown in Sierra Leone, including the logbook of the Henriqueta’s final voyage. We also have accounts from eyewitnesses to her sailings to and from her home port of Bahia (now Salvador.)

The most powerful accounts, though, come from the naval men confronted by an atrocity each time they made a capture. Many were affected, some traumatised. As one officer said: 'It is necessary to visit a slave ship to know what the trade is.'

Unseen Histories

Your story teems with slippery characters. One of the central protagonists is a Portuguese born businessman called José de Cerqueira Lima. How powerful a figure was he in the 1820s?

Stephen Taylor

Cerqueira Lima bought a new two-masted brig from Baltimore in 1824 and named her the Henriqueta. Although not his first slaver, she was the most profitable and key to the fortune he made from importing humans to Bahia and trading them on to other local entrepreneurs in an economy booming on the back of sugar and coffee.

As Portugal had become an ally of Britain, Cerqueira Lima turned his back on the motherland and campaigned furiously for Brazilian independence.

Despite losing the Henriqueta, he remained Bahia’s wealthiest, most influential magnate, and on his death in 1840 might well have claimed that he’d overcome British tyranny.

Unseen Histories

Animating the life of the sailors is a challenge. But an even greater task is trying to understand this history from the point of view of those who were being transported. Can you tell us how you sought to do this?

Stephen Taylor

It’s a narrative infused with confusion and terror. Just consider the (mainly) Yoruba men, women and children seized from their inland homes by armed fellow Africans and marched down, mystified, to sea – itself an unknown, frightening element – before being delivered into the darkened bowels of a slaveship. There a vast number died. Of all their sufferings, the traumas of the voyage were among the most intense.

Records of those rescued and taken to Sierra Leone are more illuminating. By 1830, some 23,310 former captives had been resettled. Men were given basics – a daily allowance of 3d. for six months, a small plot and tools.

Women too received a temporary income but were expected to marry. Children were schooled and some thrived: a boy named Ajayi tutored by missionaries is remembered as Samuel Crowther, the first Bishop of West Africa, who was introduced to Queen Victoria. But exceptions cannot define the fate of innumerable others.

Unseen Histories

Your story pivots on an episode in September 1827. Can you tell us what happened then?

Stephen Taylor

The Henriqueta sailed from Lagos on September 5 with 569 captives, a third of them children. At the helm was Joao Cardozo dos Santos, master on all her seven voyages. They had outrun naval pursuit before and just as Dos Santos had grown to revel in the Henriqueta’s seafaring magic, so too he’d developed a contempt for the enemy’s blundering hulks.

Cruising across the horizon that day lay HMS Sybille, a 44-gun frigate, flagship of the squadron and, in this situation, a laggard herself. Dos Santos soon sighted her, but instead of dashing on, he was seized by hubris and tried to race across her bows. Navy ships still had one skill in their lockers, and that was gunnery. The Henriqueta’s rigging was shredded. She slowed and was boarded.

Capturing such a notorious slaver, presented Commodore Francis Collier with a rare opportunity – to set a thief to catch a thief. The Henriqueta was renamed the Black Joke and attached to the squadron.

Unseen Histories

You note that during this period there is an ambivalence in the Admiralty’s attitude towards the Preventative Squadron. They would always send ships, for instance, but they would never be the best ships. Is this correct?

Stephen Taylor

Admiralty policy drew criticism even at the time. Lord Palmerston, a staunch abolitionist, reflected: 'If there was a particularly old, slow-going tub in the Navy she was sure to be sent to Africa to try and catch the fast-sailing American clippers.'

This perversity extended to forbidding the use of captured slavers to pursue others: Collier’s orders as commanding officer of the squadron were that the Black Joke could serve only as a tender, or supply vessel. Like a more renowned naval hero, Collier turned a blind eye to his orders and released her – to sail independently and battle the very atrocities she had enabled.

His strategy was rapidly vindicated. The Black Joke made her first capture within a week and followed that by taking a Brazilian brig carrying 645 slaves, a chilling record at the time.

She went on to become the most successful cruiser in the squadron’s history, taking fourteen slaveships and freeing 3,692 men, women and children. Yet Admiralty hostility endured. She was set on fire at Freetown in 1832, an enigma in maritime folklore: no record of her lines was ever taken down.

Unseen Histories

Black Joke’s feats in the Atlantic gained a little celebrity back in Britain. Can you tell us how far her fame spread?

Stephen Taylor

She had already transformed morale among officers and men when she made the squadron’s most celebrated capture. A Spaniard, El Almirante, with 466 captives was taken after a bloody battle in which the Black Joke prevailed with two guns against 14. The popular press at home, always having a taste for Navy heroics, picked up the story which was also set on canvas by the artists Nicholas Condy and William Huggins.

Another legacy was passed down from those who sailed in her. They included a crew made up largely of African mariners known as Kru and former smugglers. They loved the beauty of a ship, as sailors do, and one old hand at the El Almirante action penned a ballad to 'a noble brig, my Boys, the Black Joke is her name.'

Unseen Histories

Do you think that the Black Joke’s successive commanders, and more broadly the West Africa Squadron, are adequately remembered today? Are people familiar with their accomplishments?

Stephen Taylor

I think not. Despite the failings that undermined their efforts, these men and ships saved an estimated 160,000 Africans from slavery.

Officers like Collier, and the young lieutenants who commanded the Black Joke – William Turner, Henry Downes and William Ramsay – were serving in an age overshadowed by the glory days of Nelson but they brought the same dedication and skills to a sickening, brutal field of duty.

And at a time when much of our history-telling is mired in guilt, theirs may still be remembered as a noble endeavour 𖡹

Predator of the Seas: A History of the Slaveship that Fought for Emancipation

Yale University Press, 8 October, 2024

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0300263992

"Stephen Taylor . . . combines narrative vigor with a scholarly attention to detail to convey the morally fraught saga of the Henriqueta—as well as the wider drama of which it was a part"

– Wall Street Journal

The dramatic biography of a slaveship turned freedom-fighter―which brings new insights into Britain’s involvement in the end of the trade in enslaved people.

In 1827 the Royal Navy purchased a Baltimore clipper and renamed her the Black Joke. Assigned to the Preventative Squadron, she patrolled the west coast of Africa and freed 3,692 captives from enslavement. Beloved by seafarers and celebrated by the public, the Black Joke would become the most famous weapon in the campaign for abolition.

But in her previous life as the Henriqueta, the Black Joke had been a slave ship. Through the experiences of slavers and abolitionists, captives and crew, Stephen Taylor charts the vessel’s extraordinary double life. As the Henriqueta she operated as an engine of atrocity, trafficking over 3,000 captives to plantations in Brazil. But subsequently manned by British seamen and Liberian Kru, the Black Joke became the scourge of Spanish and Brazilian slavers. She did so despite limited resources, neglect, and even obstruction by the authorities at home.

Taylor offers a gripping account of the world of the transatlantic trade, through the eyes of its perpetrators―and those who sought its end.

"The unlikely story of HMS Black Joke makes it the perfect subject for Taylor … Focusing on one ship and its changing crews provides a superb frame for his expert narrative, bringing to life the human tragedy of slavery in a way that flatly statistical books rarely achieve."

– Daniel Brooks, The Telegraph

'Ovid among the Scythians' (⇲ Met Museum)

'Travelling Boat being Rowed' (⇲ Met Museum)

'The Trojan Women Setting Fire to Their Fleet' (⇲ Met Museum)

'Sheet-gold decoration for a sword scabbard' (⇲ Met Museum)

'Reconstruction of Pomponius Mela's world map by Konrad Miller [de] (1898)' (⇲ Wiki Commons)

Notes

With thanks to Yale University Press