Prelude

Leah Broad introduces us to four women who changed the musical world

Ethel Smyth. Rebecca Clarke. Dorothy Howell. Doreen Carwithen. In their time, these women were celebrities. They composed some of the century’s most popular music and pioneered creative careers; but today, they are ghostly presences, surviving only as muses and footnotes to male contemporaries like Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Britten – until now.

Leah Broad’s magnificent group biography resurrects these forgotten voices, recounting lives of rebellion, heartbreak and ambition, and celebrating their musical masterpieces. Lighting up a panoramic sweep of British history over two World Wars, Quartet revolutionises the canon forever.

With an introduction by Leah Broad

Composers Ethel Smyth, Rebecca Clarke, Dorothy Howell and Doreen Carwithen were once famous figures. Their music was heard in concert halls, homes, cinemas, theatre and in the streets. But they have since become ghosts haunting the pages of the men who they worked alongside, lived with, and sometimes loved. They led extraordinary lives and wrote exquisite music – their stories deserve to be heard.

– Leah Broad

For references please consult the finished book.

On a bleak day in March 1930, a crowd of smartly dressed women gathered outside London’s parliamentary buildings. For many of the older women, it was not the first time that they had convened in the long shadow of Victoria Tower, its Gothic arches reaching up to the pale grey sky. As members of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the militant suffrage organisation led by Emmeline Pankhurst, they had all marched on the House of Commons in support of women’s right to vote. Now, their lapels bore medals reading ‘For Valour’, awarded to those suffragettes who had gone on hunger strike while imprisoned for the cause.

As rain threatened to mizzle through the park, an elderly woman stepped forward, clad in a fine silk doctoral robe and cap. This, in itself, was a symbol of women’s changing status: women had only begun to be awarded British degrees from 1878, and in 1910 this lady became one of just three women in England to hold a music doctorate. Brandishing a conductor’s baton, she exuded an air of ‘enormous eagerness’, still ‘indomitable & persistent’ in her seventies, with blue eyes that ‘positively glitter’ under untameable wisps of grey hair.

Her presence immediately brought an energy and vigour to the proceedings, the women cheering visibly as she led the Metropolitan Police Band in a rousing rendition of The March of the Women, the suffrage anthem she had composed herself in 1910. All suffragettes knew the March by heart – it had been sung at rallies, in prisons and at meetings – and now it brought tears to the eyes of the older women to hear their battle song again, played by the very men who had once arrested them.

The woman was Dame Ethel Smyth, ‘the greatest woman composer in the world’, as one newspaper called her, numbering her ‘among the most “militant” of the Suffragettes’. Never one to suffer fools gladly, she had been jailed for bricking the windows of a politician who made ‘the most objectionable remark about Women’s Suffrage she had ever heard’. Ethel was certainly among the women in the crowd for whom this event was especially moving – not only had she fought alongside Emmeline and been imprisoned with her, but she had been her closest friend and possibly her lover. The composer was always circumspect about revealing the intimate details of her relationships, but one of her later passions, the writer Virginia Woolf, revealed that ‘Ethel used to love Emmeline – they shared a bed’. It must have been a poignant moment for Ethel, seeing Emmeline’s familiar features revealed, now cast in bronze, caught forever as Ethel remembered her best, mid-speech with hands held aloft, convincing her listeners of the importance of her cause.

Among the pieces Ethel conducted was a Minuet by her younger contemporary, thirty-two-year-old Dorothy Howell. When Ethel and Emmeline were incarcerated in Holloway, Dorothy had still been in school, only just beginning to follow in Ethel’s footsteps by taking private composition lessons. A quiet, unassuming woman, Dorothy led a far less unorthodox life than Ethel’s – the two women could not have been more different if they had tried. While Ethel had numerous love affairs with both men and women, Dorothy remained resolutely single; Dorothy was Catholic, but Ethel could never quite embrace Catholicism.

And yet they were bound together by music. Ethel staunchly supported Dorothy’s compositions, insisting that her music be heard at the unveiling even when Dorothy modestly worried that her contribution might ‘let women down’. Despite their differences of age and outlook, they became threads in the rich tapestry of each other’s lives. It was almost inevitable that their paths would cross at some point. Women composers were a rarity in England, and were often grouped together by programmers.

Suffragette, pioneer and activist Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) is the grande dame of Quartet. Women had been composing before her, but she was the first to really force musical institutions to confront their gender problem. She demanded to be given the same rights as men and to be treated equally, and for her compositions not to be judged by a different standard because of her gender. Rather than remain content with being a teacher or domestic music-maker, Ethel rebelled against the roles that had been carved out for musical women in Victorian society. On the golf course opposite her cottage in Surrey, she taught Emmeline Pankhurst to throw stones to hit a target, and when the two suffragettes were later arrested for property damage they were jailed in cells next to one another. In true Ethel style, she responded to her incarceration by rousing choruses of imprisoned women to sing The March of the Women in jail, conducting from her cell window with a toothbrush.

Ethel was truly unusual for her time. Her life is completely unrepresentative of the experience of most women composers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Indeed, she was lucky she was embraced as an eccentric and not institutionalised as a lunatic. Few could lead a life as bold as hers. Few, perhaps, would want to.

Rebecca Clarke (1886–1979) was one such composer who came of age in Ethel’s wake. Like Ethel she was outgoing, fun, and had a wicked sense of humour. But in most ways she was Ethel’s opposite. Rebecca was elegant and stylish, always dressed in the latest fashions. With her long dark hair and tall, slender figure, she wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Pre-Raphaelite painting. She hated being at the centre of a scandal. Nor did she want to be seen as a ‘woman composer’. Rebecca was born nearly three decades after Ethel, and by the time she was premiering her first works it was far more normal for women to be successful musicians. Where Ethel had been forced to foreground the fact that she was a woman, demanding equal treatment with men, Rebecca preferred to say that gender was irrelevant. In private she may have been outspoken on the issue, but her hatred of being pigeonholed as a ‘woman composer’ meant that she rarely expressed forthright support for women’s causes.

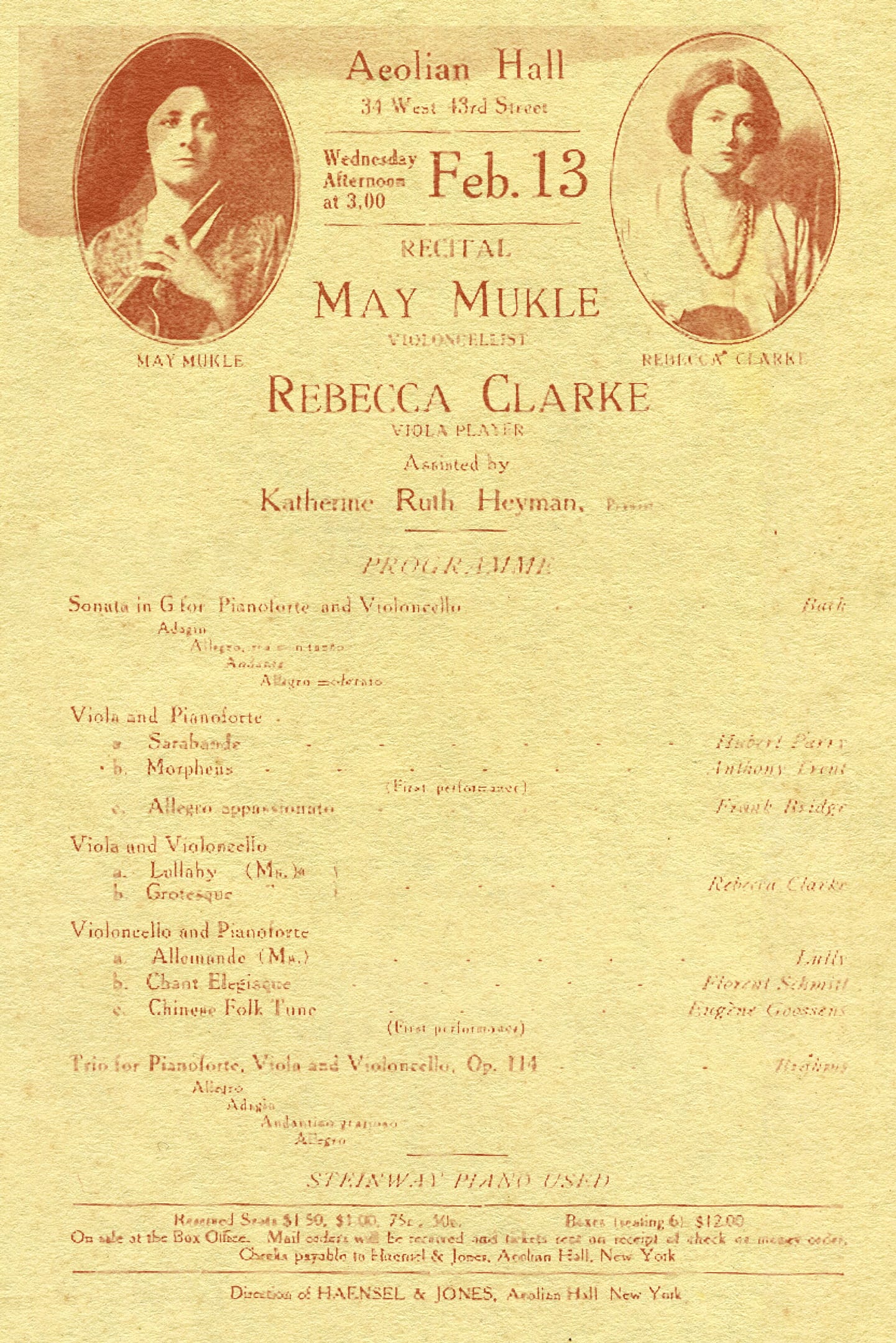

Rebecca’s feelings about feminism were also shaped by the fact she split her career between the UK and the USA, where attitudes towards women composers were sometimes more accommodating than in Britain. Rebecca’s career was a whirlwind of triumphs and breakthroughs. A talented violist, she made history in 1913 by becoming one of the first six women in the world to be hired by a professional orchestra. With her best friend, cellist May Mukle, she toured not only America, but went as far afield as Singapore and China. And, confident in the quality of her music, she was not one to hide her light under a bushel. Rebecca began composing while figures like Ralph Vaughan Williams, now most famous as the composer of The Lark Ascending, dominated the UK scene. She worked alongside them very much as their equal, and was taken seriously by critics as an important modern composer.

Dorothy Howell (1898–1982) was far less outlandish and altogether more reserved than either Ethel or Rebecca. She was unfailingly modest, and knew her own mind. Billed by the press as a child prodigy when, aged twenty-one, she had a major success with an orchestral work called Lamia, she nonetheless seems to have been unaffected by the media frenzy that surrounded her. She delighted in writing whimsical pieces with titles like ‘Tortoiseshell Cat’, ‘If You Meet a Fairy’ and ‘Puddle Duck (with apologies to Beatrix Potter)’.

Drama didn’t follow Dorothy as it did Ethel. She was warm and gentle and generous, and remembered fondly by those who knew her. Like Rebecca she loved fashion, and was constantly going on shopping trips to buy new concert dresses, hats and shoes. But she didn’t seek to stand out from the crowd. Dorothy had conservative tastes – her dresses were demure, and she kept her hair short and simply cut. As in clothing, so too in her lifestyle and in her music. When she first heard the dissonant, jarring sounds that would come to dominate ‘modern’ twentieth-century music, she reacted not with horror or panic, as many musicians did, but with amusement. Unfazed by modern trends, she always wrote melodious music that she felt was true to her, and she found a supportive home for her work within the Catholic Church.

The last of the quartet, Doreen Carwithen (1922–2003), led a life completely out of the limelight. Of all the personalities in this book, Doreen is perhaps the most complex. She looks so approachable in photographs, with her curly hair and endearingly lopsided smile that could blossom into the most candid grin when she found something genuinely funny. And yet she’s something of an enigma. In her early diaries and letters she comes across as a hard-working, earnest woman. She needed her own space – she frequently wrote about needing to find time away from her boisterous and noisy family members – but she had plenty of friends and a packed social schedule. And yet those who knew her at the end of her life describe her as difficult, belligerent and exacting. She had very few friends at the time of her death, having pushed away many of those close to her.

Her career follows a similarly perplexing trajectory. In her early years she was one of the stars of the Royal Academy of Music where, like Dorothy, she studied piano and composition. She was one of the first students to be accepted on to a scholarship programme to score films, and was the only woman in her cohort. She would become one of the first British women to work predominantly as a film composer. And yet by the 1960s Doreen’s name had all but vanished from concert programmes, and by the 1970s she had stopped composing altogether. What happened?

History is full of women like these, who were famous in their lifetimes but have since become ghosts who haunt the pages of books dedicated to the men they worked with, talked with, and sometimes loved – men like Ralph Vaughan Williams and Benjamin Britten, who are today considered indispensable to the story of British music in the twentieth century. Quartet makes an unapologetic case for the importance of women in music history, and analyses both the obstacles that women faced, and the ways that they found to overcome them and assert their agency in a world where the odds were stacked against their success.

I have chosen the four women in Quartet for a number of reasons. First, they all wrote exquisite, breathtaking music. Second, they all achieved things that are still considered ‘extraordinary’ for women, even today. By the middle of the twentieth century there were sufficiently large numbers of women working as composers that it was far more difficult to choose who to include than who to leave out – but Doreen stands out for her under-appreciated music, her fascinating private life, and her career being mainly in film music. Even in 2018, only 6 per cent of the highest-grossing films were scored by a woman. Similarly, Ethel was best known as a composer of operas, and yet 2019 was the first year that the Vienna State Opera performed a work by a woman.

Crucially, though, none of the women in Quartet could have been strongly aware of their predecessors because history books of their period simply didn’t include them. Historical forgetting is such a powerful form of erasure. It robs women of role models, and leaves them going in circles, repeating the same ‘breakthroughs’, diverting valuable energy and resources from real progress. It’s because of this historical tendency to forget and isolate women that Quartet is a group biography. It could have been the story of just one woman: any one of them could (and hopefully will) be the subject of countless volumes of books. But it is important that each of these women is not ‘the only’ today, any more than in their own lifetimes. While male critics could bluster all they liked, music just wasn’t as much of a man’s world as they tried to suggest. Professional musical women may have been in a minority in the early 1900s, but they were there and they were often extremely successful.

Accordingly, one thing that unites all four women is how important networks were for building their careers. And these were often networks made up mostly of women. When musical women found doors closed to them, they turned to one another for support. Sometimes this meant performing each other’s music – Doreen’s best friend Violet Graham premiered her Piano Sonatina, while Rebecca played in various chamber groups with some of her closest friends – and sometimes they gave help in financial form.

Being a composer was an expensive business, especially if you were a woman. If Ethel wanted one of her orchestral works performed, she had two options. First, she could wait for an interested conductor to take up the work – but as she repeatedly pointed out, conductors were extremely unlikely to perform music by women. The second option was to hire the venue and players herself, and try to cover costs with ticket sales. Faced with this ongoing problem and finding herself locked out of the ‘Old Boys’ network that played each other’s works at festivals – whom she called the ‘Machine’ – Ethel built herself an ‘Old Girls’ network of wealthy and famous women patrons who supported her unfailingly.

In her lifetime Ethel was criticised for her dense thicket of friendships, accused of letting them distract her from her work. She replied cuttingly that ‘if the world is inclined to scoff or speak ill of women’s friendships, this is one of those cheap generalities which will pass muster only as long as women let men do their thinking for them’. As far as she was concerned, her many relationships with women were the ‘shining threads in my life’. Without them, she would not have had a career at all.

The sheer number of financial and social barriers to becoming a composer meant that the profession all but excluded working-class women. It’s no coincidence that all the women in Quartet were middle class – whether upper middle class like Ethel, or moving between the lower middle and middle middle classes like Rebecca. It wasn’t impossible for women in either the upper or working classes to have musical careers, but the upper classes were heavily restricted by social expectations, while the sheer cost of musical tuition was out of reach for the majority of working-class women – to say nothing of the later costs of staging concerts or the advantages of having wealthy social connections.

Although the composers in Quartet faced a plethora of obstacles and were disadvantaged by their gender, their class and race also gave them positions of relative power and privilege. Focusing only on the difficulties that women faced risks presenting them as victims, and the reality is far more nuanced than that. These women had individual agency, and used what structural advantages they had to effect change for themselves and for others, finding inventive ways around prejudice to forge careers against all the odds. Their stories are as much about empowerment and self-determination as they are about setback and limitation •

This excerpt was originally published August 10, 2022.

Quartet: How Four Women Changed The Musical World

Faber, 2 March, 2023

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-0571366101

“A wonderful, gripping, page-turning read” – Kate Mosse

Ethel Smyth (b.1858): Famed for her operas, this trailblazing queer Victorian composer was a larger-than-life socialite, intrepid traveller and committed Suffragette.

Rebecca Clarke (b.1886): This talented violist and Pre-Raphaelite beauty was one of the first women ever hired by a professional orchestra, later celebrated for her modernist experimentation.

Dorothy Howell (b.1898): A prodigy who shot to fame at the 1919 Proms, her reputation as the 'English Strauss' never dented her modesty; on retirement, she tended Elgar's grave alone.

Doreen Carwithen (b.1922): One of Britain's first woman film composers who scored Elizabeth II's coronation film, her success hid a 20-year affair with her married composition tutor.

In their time, these women were celebrities. They composed some of the century's most popular music and pioneered creative careers; but today, they are ghostly presences, surviving only as muses and footnotes to male contemporaries like Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Britten - until now.

Leah Broad's magnificent group biography resurrects these forgotten voices, recounting lives of rebellion, heartbreak and ambition, and celebrating their musical masterpieces. Lighting up a panoramic sweep of British history over two World Wars, Quartetrevolutionises the canon forever.

“Quartet is much more than a book about four talented, pioneering female musicians. It is also a sweeping social history of the last century with intertwined themes of sex and politics, inspiring and shocking by turns ... They all wrote exquisite, breathtaking and often highly original music which is only now being finally appreciated ... Their time has come”

– The Specator

“Broad's fabulous study of four groundbreaking British female composers ... Each of Broad's quartet deserves a book to herself, but together they carry this story through the seismic transformations of their world, society and technology. All wrote superb music; each struggled in her own way for performances, recognition and a legacy”

– The Sunday Times

Further Reading

Leah Recommends

⇲ Sound within Sound by Kate Molleson (Faber and Faber, 2022)

⇲ Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music by Anna Beer (Oneworld, 2017)

⇲ Warrior Queens and Quiet Revolutionaries: How Women (Also) Built the World by Kate Mosse (Mantle, 2022)

Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics by Bell Hooks (Pluto Press, 2000)

With thanks to Lauren Nicoll at Faber. Author Photograph © Monika Tomiczek.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store