Reasons to Live – A Reconciliation with Mahmoud Darwish

Mai Serhan reflects on an encounter with the great Palestinian poet

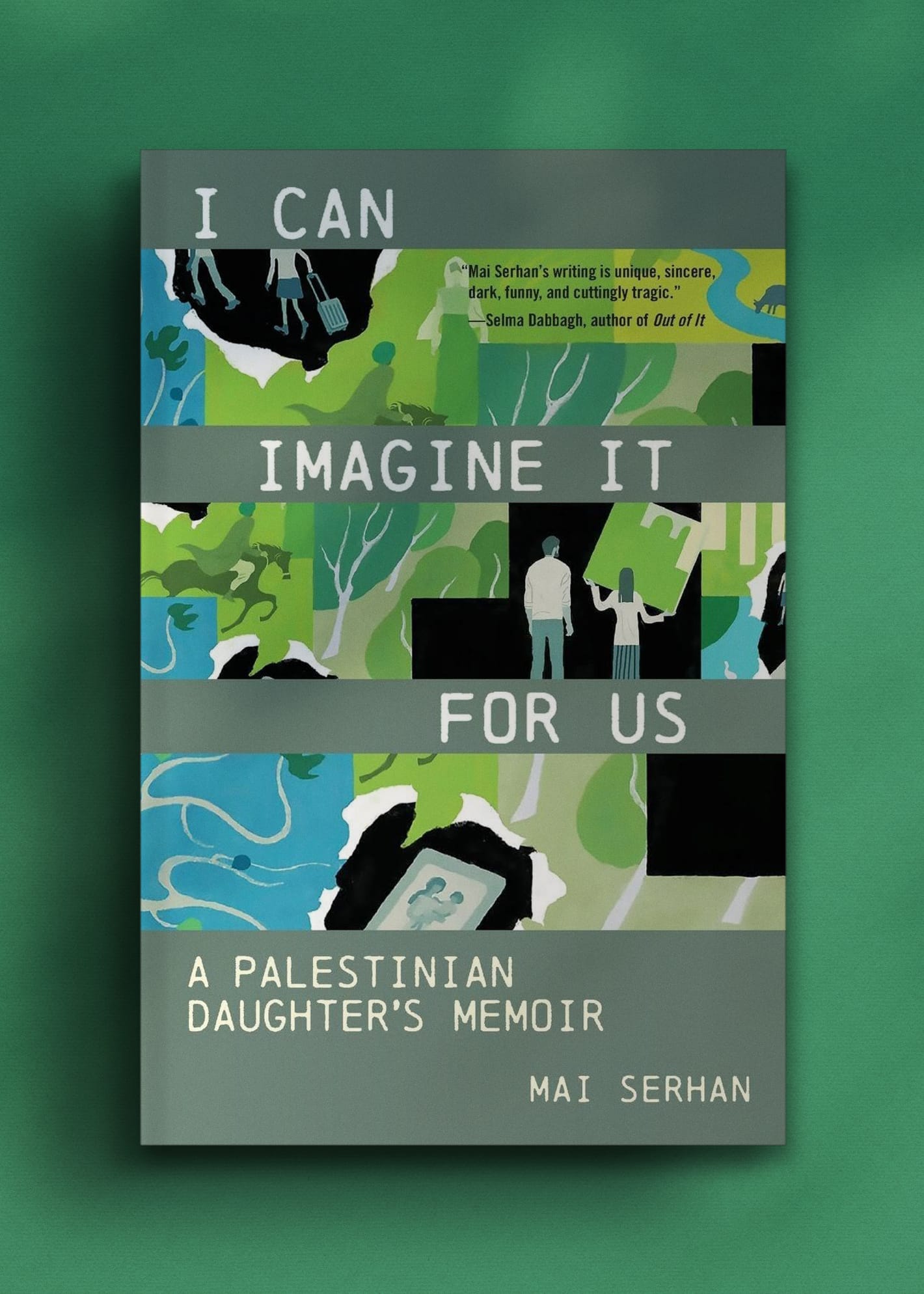

Here Mai Serhan, the author of I Can Imagine It for Us: A Palestinian Daughter's Memoir, explains how ideas of unity and resistance have shaped her own writing.

Serhan's book is one of patterns and connection and one of these, like 'a key clicking open an old door', took place this September as she listened to the words of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

I have an admission: I resisted Mahmoud Darwish for years. Five years ago, a friend gifted me one of his poetry collections, and I tucked it away, unread. Maybe I wasn’t ready. Perhaps something in me couldn’t yet see my Palestine in his words. Or thought it was a faded echo of his own.

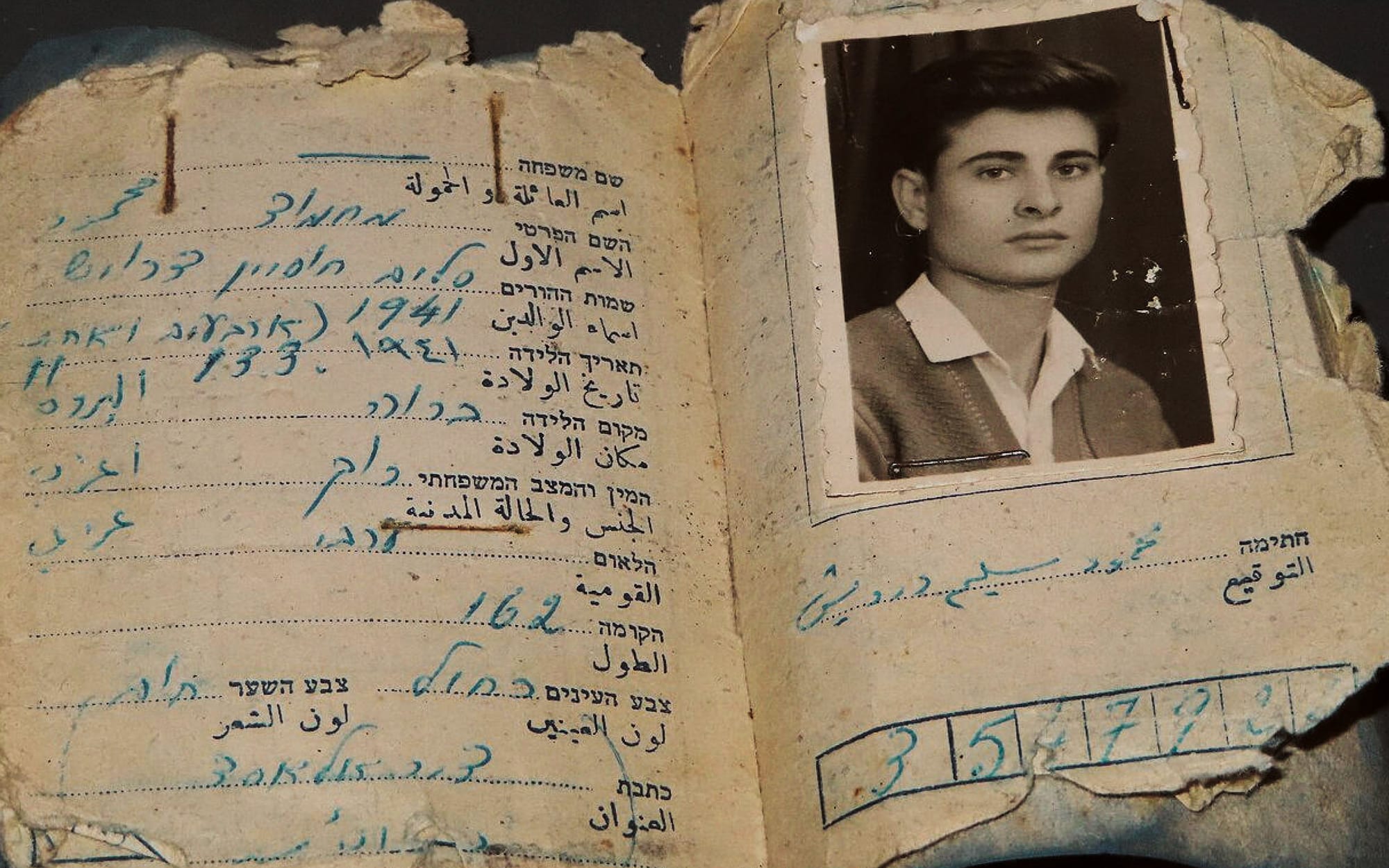

I’m a second-generation Palestinian in the diaspora, born and raised elsewhere, to an Egyptian mother; Darwish was born in Palestine and though he was forced into exile, his body was returned home for its final resting place.

My severance from my origin home shapes not only what I write, but how. I write about international codes, airplanes, and fast food in transit; Darwish writes about the olive tree, about roots that run deeper than my reach. My words long in alienation, in English; Darwish is seen as a national leader, he wrote from the center, in the mother tongue. While he is an enduring symbol of Palestine itself, I write from post-memory. In all these contrasts, I suppose I feared I did not belong.

But that distance collapsed post-October 7.

My positionality vis-à-vis the homeland went through a few shifts. At first, I mirrored. I didn’t eat because Gazans are left to starve. I could not sleep while drones flew over their heads. I did not write – I could not find a word in the dictionary for what is more surreal than hell.

The distance between me and the place where I’m from was dissolving, yes, but in a destructive way. A year in, despair hardened into numbness. I doom-scrolled past horrors as quickly as I would a sponsored ad for Bookings.com. Two years in, a friend in New York messaged me. She told me to tune into Together for Palestine, a live benefit concert for Gaza held at London’s Wembley Stadium.

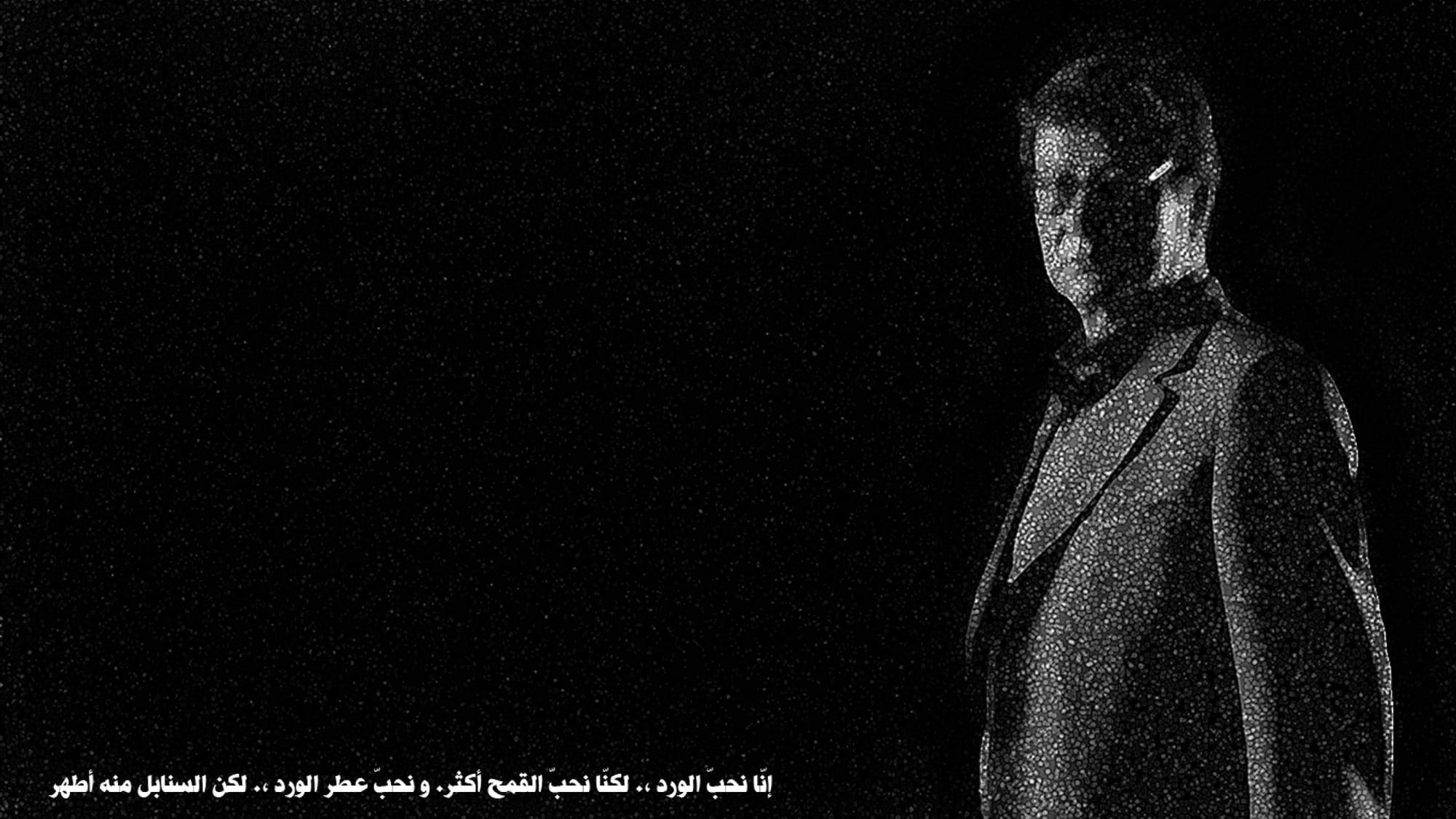

She sent me a link. On the screen, Benedict Cumberbatch and Palestinian playwright Amer Hlehel recited Darwish’s poem On This Land:

She was known as Palestine

She forevermore will be known as Palestine

My land, my lady, you are a reason to live.

I listened like a landing, like a key clicking open an old door: Twelve thousand people were at that stadium, but they might as well have been one. Darwish’s words had crossed over time and space, and arrived intact. They arrived in a global language. They made the land tangible, the truth, inalienable. They pledged continuity.

In the months that followed, I found myself returning to Darwish again and again, tracing the lines between us. That renewed attention accompanied me into a new chapter of my own life. Now, as I reconnect my coordinates towards his enduring influence, I am also engaged in press for my new book, I Can Imagine It for Us: A Palestinian Daughter’s Memoir.

A few things strike me about this moment. Here I am, trying to make sense of being my own kind of Palestinian, while also having to explain myself through ancestry, my father – and, unexpectedly, Darwish.

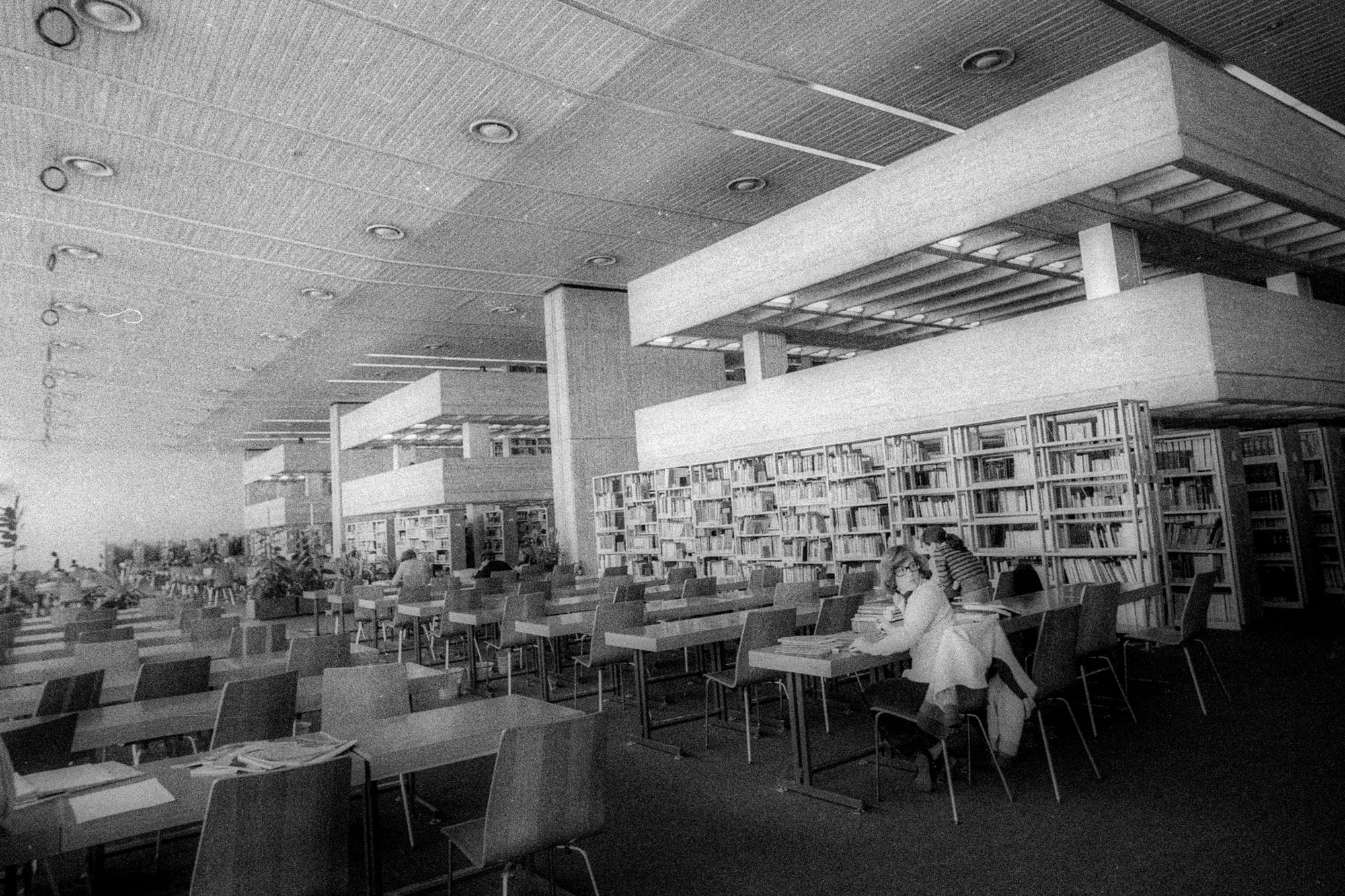

In a recent book discussion, I was asked why I chose memoir over fiction to tell this story, especially since it is so deeply revealing. I answered with something about reclamation, about ownership in the face of erasure, but I also validated my choice by referencing Identity Card, the poem Darwish penned in Haifa, that placed him under house arrest.

Today its refrain, 'put it on record/I am an Arab,' is interchangeable with the title. Today, the poem is a protest song. That same impulse, to protest, to own what is yours despite the mechanisms of disenfranchisement, is precisely why my story could be nothing but a memoir.

In another interview, I was asked about my father, how I shape him from absence, from silence, much as I do with Palestine, and still feel compelled to hold them both on the page. Why?

Well, because words allow me to register their presence, to reconstruct them both; to give a name, sow a seed, see a country. My father’s story is the reason why I write, he is my long view of history, much like Darwish’s lady known as Palestine is forevermore reason to live – because to write the story is to resist death.

In this ongoing pursuit of life and afterlife, I am struck by a newfound sense of succession, by patterns that concur and deflect. The Palestinian experience is a vast and varied tapestry, but it is made to hold. It holds loss, estrangement, return, cultural survival and memory with variations on the stitch. It weaves metaphors, and the countless paths that carry our stories forward. In Palestinian, we call this kind of holding on, sumud.

Finally, there is the inevitable question I keep getting asked: Why do you write in English?

It’s a query that has always irked me. I see it as underhanded, it chooses to alienate rather than integrate, as if to suggest that writing in English makes one somehow less Palestinian.

Perhaps the irritation the question triggers comes from knowing that the answer is anything but simple. The generic reply would be because colonial structures continue to shape the Arab world; the army barracks may be gone, but the military bases, economic dependency and cultural hegemony remain.

The specific answer, however, is more elusive. It involves the many roads Palestinians have travelled since 1948, their alien status and foreign passports. English is the lingua franca of our second-generation in the diaspora – my primary audience, seven million strong and scattered all over.

But I also write in English to reach you, the Western reader, living in the belly of empire, who rarely encounters Palestine in school curricula or news soundbites, or encounters it only through a distorted lens.

As I think of language and audience, I again return to Darwish; how On This Land crossed over to a global audience, in the tongue of empire. I think of its life and afterlife, how it moves between the space of knowing and digressing, and how this movement is the watermark of our collective.

When I began writing my memoir, I had barely any country to recall, so I had to digress, to imagine it for us. And yet in untucking Darwish, I came to understand that my Palestine expands in the space between his knowing and my imagining. To imagine is to assemble what we cannot access directly from what we do know – what something feels like, what it could mean, what it might become. It becomes the way in which we touch •

This feature was originally published December 18, 2025.

I Can Imagine It for Us: A Palestinian Daughter's Memoir

The American University in Cairo Press, 14 October, 2025

RRP: £14.99 | 236 pages | ISBN: 978-1649034595

A young woman’s search for connection with her estranged father, her family’s past, and the Palestinian homeland she can never visit.

Mai Serhan lives in Cairo and has never been to Palestine, the country from which her family was expelled in 1948. She is twenty-four years old when one morning she receives a phone call from her estranged father. His health is failing and he might not have long to live, so he asks her to join him in China where he runs a business empire about which Mai knows nothing. Mai agrees to go in the hopes that they will become close, but this strange new country is as unknowable to her as her father. There, the ghosts of the Nakba come to haunt them both. With this grief comes violence, and a tragic death brings a whole new meaning to the word erasure.

In a narrative made rich by its layers of fragmentation, as befitting the splintered and disordered existence of exile over generations, this courageous memoir spans Egypt, Lebanon, Dubai, China and, of course, Palestine. It is filled with bitter tragedy and loss and woven through with an understated humor and much grace.

“Serhan’s memoir, crafted in magnificent prose. . . . is something which is truly cinematic in quality, whose delights and heartbreaks tumble out before the reader as naturally as images fall from a screen. . . . utterly vivid and compelling”

– Jhalak Review

With thanks to The American University in Cairo Press.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store