Samuel Johnson and the Perils of Hope

On the anniversary of Johnson's birth, Peter Moore considers a subject that deeply engaged the great writer.

In progressive societies 'hope' is often celebrated as a vital force. It is something that drives people forwards and fires their imaginations. To live without hope, to be hopeless, is the most wretched of all conditions.

In his great essays about the human condition, the eighteenth-century author Samuel Johnson wrote frequently about this. But while he acknowledged hope's central place in life, he repeatedly warned people against hoping too much.

To do so, Johnson believed, was more likely to bring misery than happiness, as Peter Moore explains.

In 1750, when Samuel Johnson began his essay series, The Rambler, he took care to fortify himself against an ailment he called ‘The Writer’s Malady’. This was something he had often observed during his years as a jobbing hack in Fleet Street. It generally appeared in the hours after a writer was struck by an idea for a poem, essay or book. Charged with excitement they would soon be touring the printers and the booksellers to tell them all about it.

Many did not stop even there. Johnson would watch keenly on as these writers gazed into ‘futurity’ – the utopian future world –, a place of anticipated wealth, happiness and honour.

Johnson enjoyed poking fun at his own trade. In the mid eighteenth-century, print journalism was in the boisterous phase of its infancy and there were many, like him, who had travelled to London to become ‘adventurers in literature’.

But writers were not alone in allowing their minds, as Johnson put it, ‘to riot in the fruition of some possible good’. Not far from where he lived, in the coffee houses of the Strand or the City, it was common to cross paths with speculators plotting voyages to the East; or ‘projectors’ (the entrepreneurs of the day) with their get-rich-quick schemes; or fellows of the Royal Society, absorbed in their latest theories.

For Johnson these figures, just as much as his literary friends, were guilty of living ‘in idea’.

I have been thinking about the similarities between Johnson’s world and our own recently. Both are expansive ages of heightened individualism when a disruptive new media loudly promises opportunities that would have been unimaginable to previous generations.

In the Georgians who gazed so intently into futurity, we can glimpse an early incarnation of the ‘manifesters’ of today, striving to will their goals into existence. In Johnson’s many tales of restless, questing Londoners that fill the pages of The Rambler, we can see people contending with that sensation Oliver Burkeman has recently labelled ‘existential overwhelm’ – when the sheer number of things that a person can do far outstrips the time available to do them.

All this gives Johnson’s writing a relevance. He is most familiar to us today for his great Dictionary of the English Language. In his own time, however, he was equally known as a ‘moralist’, or, as he defined it himself, ‘one who teaches the duties of life’.

This was the persona Johnson adopted in The Rambler, a periodical in which he set out to expose and evaluate the eternal challenges of human existence. One of the essays from this series that has most engaged me is The Rambler No.2, which he titled The Necessity and Danger of Looking into Futurity.

In this Johnson framed a dilemma. Because of the slow and progressive nature of life, he argued, it was vital that people looked into the future for inspiration. It was there that they could identify, ‘new motives of action, new excitements of fear, and allurements of desire’. These were the crucial motivations people needed to power themselves forward through the trials of existence.

To Johnson, however, this process, which should have been simple and rhythmical, was complicated by a quirk of nature. Humans were temperamentally given to fixating on the future, or, as he put it in one of his most luminous aphorisms, ‘The natural flights of the human mind are not from pleasure to pleasure, but from hope to hope.’

Read today, this quote has a felicitous air. ‘Hope’, after all, is a word we regard with strongly positive connotations. It symbolises promise and implies action. It is closely bound up with that peculiarly Western ideal, ‘the pursuit of happiness’. As a quietly radical force, it was best captured by a young Barack Obama in his career-igniting speech to the Democratic National Convention in 2004.

‘Hope’, Obama proclaimed. ‘Hope in the face of difficulty. Hope in the face of uncertainty. The audacity of hope.’

Johnson regarded hope in very different terms. As Walter Jackson Bate explained it in his Pulitzer Prize winning biography, hope for Johnson was an emotion that existed in the fraught realm of the human imagination.

This was not a ‘serene, objective, rational’ place, which was suited to making calm decisions, but rather a part of the mind that was restless, devouring and ‘unpredictably alive in its own right’. Johnson, Bate argued, was perhaps the first to see the human mind in this way. His revolutionary insight - one greatly ahead of its time - was to view the imagination, along with its tendency to hope, dream and wish, as something that could just as easily produce misery as happiness.

Johnson’s own London neighbourhood teemed with cautionary tales. While it was certainly a place of energy and ideas, the maze of courts and alleyways around Fleet Street were also filled with Hogarthian horrors: of violence, destitution and squalor.

In The Rambler No.2 Johnson provide

d his readers with some practical advice, to spare them from the same fate. He argued that to guard against the lures of hopeful ideas, people should learn to check themselves. A wild imagination needed to be regulated by reality.

One of Johnson’s own tricks was to remind himself of the ‘sage advice’ of the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus. Born into slavery in Hierapolis, in modern-day Turkey, about 2,000 years ago, Epictetus was someone who had frequently experienced disappointment.

Johnson recalled one of his teachings: that a person should accustom themselves ‘to think of what is most shocking and terrible, that by such reflections he may be preserved from too ardent wishes for seeming good, and from too much dejection in real evil’.

To us this might seem like unnecessarily powerful medicine. Johnson, the famously tortured genius with his intense neurosis, may well be considered a bad model from which to draw an example. But in some ways our society is an even more perilous one than his.

Today we live in world where computers often know our hopes just as well as we do. These hopes are flashed before us, day after day, in an endless stream of targeted ads that seek to capture and activate our imaginations in an increasingly number of inventive and effective ways. In such a world, a little Stoic philosophy is a useful antidote.

As for Johnson himself, he claimed to be ‘lightly touched’ with the writer’s malady.

And yet if we look back to his situation in the year 1750 we find him struggling along with his huge dictionary project. To many of his friends at the time this was the ultimate case of hubris: a project so wild in its ambition that it was almost guaranteed to fail.

That it did not and that it turned out to be one of the scholarly achievements of the century shows us what great hopes can produce.

But that Johnson could know so much about the workings of the human mind and still place himself in such danger underscores, as eloquently as anything, the power of the imagination.

‘Hope’, Johnson wrote in the Dictionary, ‘An expectation indulged with pleasure’. The note of caution is plain •

This feature was originally published September 18, 2024.

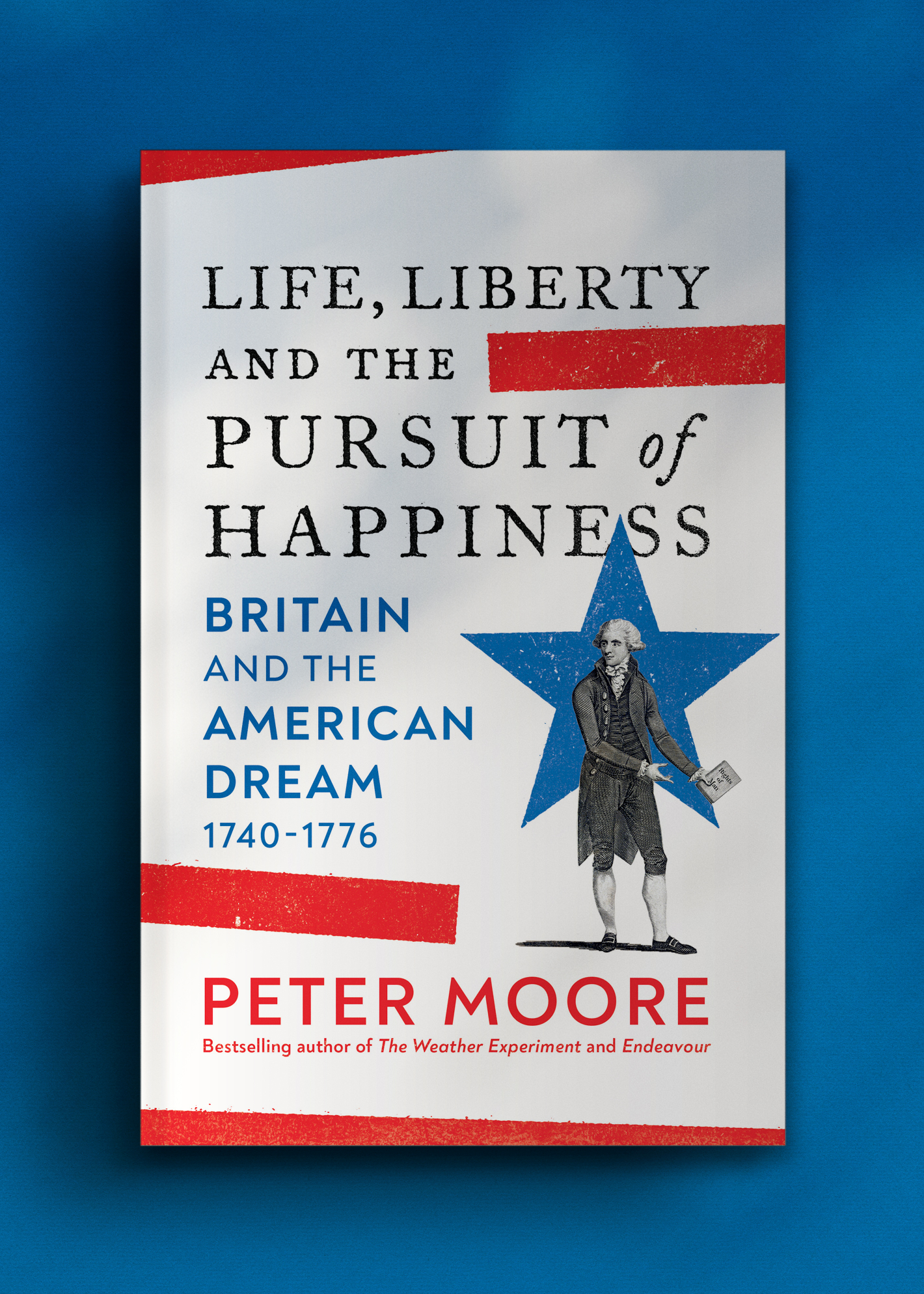

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness: Britain and the American Dream

Chatto & Windus, 25 June, 2023

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1784743192

“Rollicking...compulsive readability” – The Washington Post

Bestselling historian Peter Moore traces how Enlightenment ideas were exported from Britain and put into practice in America - where they became the most successful export of all time, the American Dream

Enlightenment Britain was ablaze with ambition and energy. Great writers like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Samuel Johnson, John Wilkes and Catharine Macaulay were part of a pioneering generation that shaped and inspired the American Dream. For the first time, bestselling historian Peter Moore vividly traces the transatlantic friendships and revolutionary ideas that inspired the Declaration of Independence.

Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness is the best-known phrase from that document, which was drafted by Thomas Jefferson in the summer of 1776. Today this line is evoked as a shorthand for that ideal we call the American Dream. But the vision it encapsulates – of a free and happy world – has its roots in Great Britain.

This book tells the story of the years that preceded the Declaration. From the accession of King George III to the astonishing tale of John Wilkes, from the notorious Stamp Act to the Boston Tea Party, it shows how Britain and her American Colonies broke apart.

Following a star cast of Enlightenment characters, through their letters, arguments and rivalries, it reveals the rise of a rebellious and daring ideology – one that gave rise to the democratic birth of the United States and the principles we live by to this day.

“[An] absorbing book... Moore has a keen eye for the sort of eloquent detail that enlivens biography, and he expertly evokes Franklin's transformation from proud artisan to member of a new American elite. He's particularly good on the quirkiness of Franklin's early adulthood . . . Moore [is] a crisp writer and adept at narrative sweep”

– Henry Hitchings, The Times

“History is best written by the losers. In Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, Peter Moore... shows how Britain exported its highest ideals to the Americans who rejected it”

– Dominic Green, Wall Street Journal

With thanks to WJB.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store