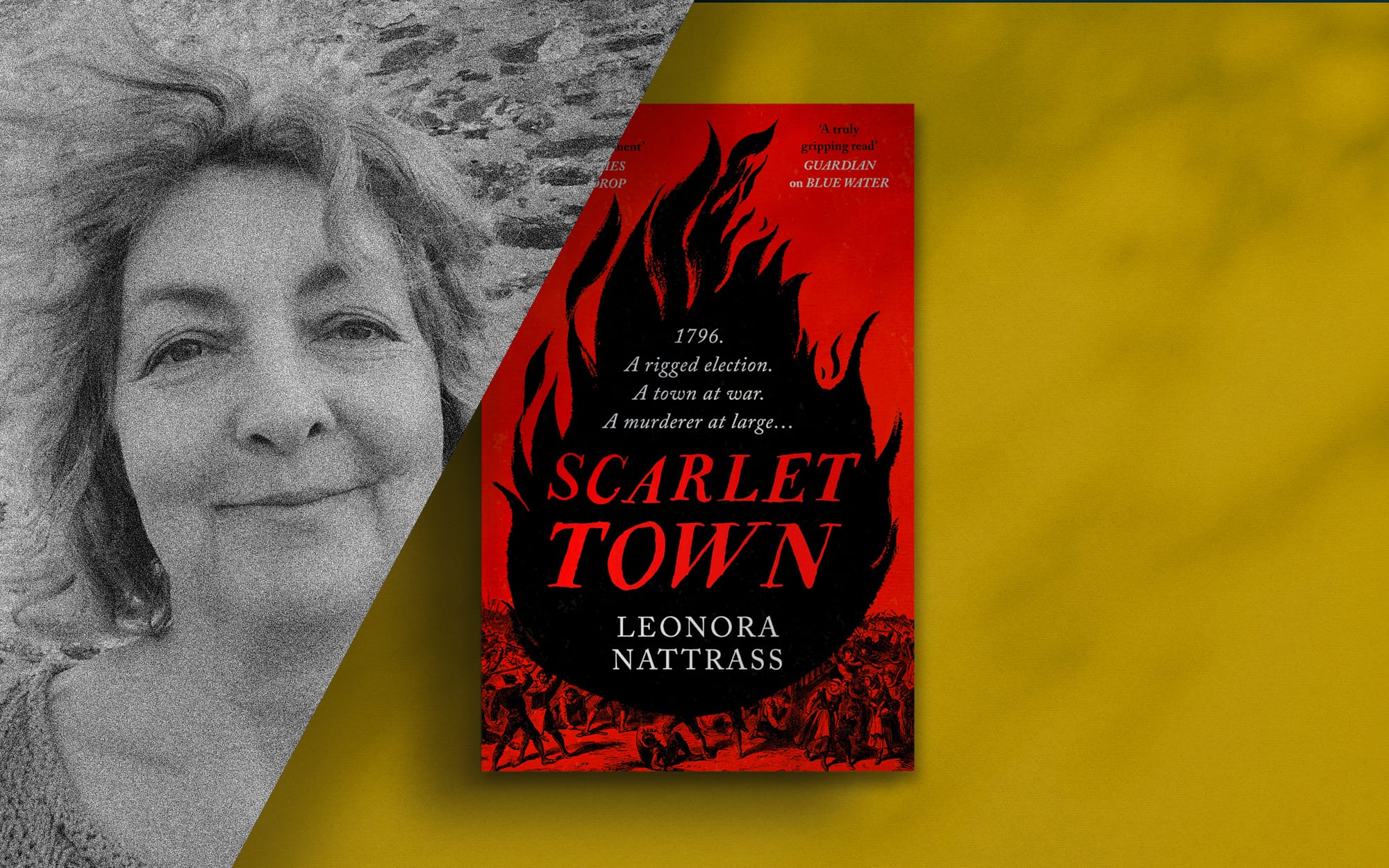

Scarlet Town with Leonora Nattrass

Leonora Nattrass on the paranoid politics of the 1790s

Leonora Nattrass's 'Laurence Jago' series of historical novels has been widely acclaimed. Set in the boisterous 1790s, they have already examined the worlds of espionage and diplomacy. This week the third book in the series is published. In Scarlet Town Nattrass takes us to the town of Helston in Cornwall.

Here, in the year 1796, an election is underway. A generation before the Reform Act of 1832, this makes the perfect backdrop for dramatic fiction, as Nattrass explains.

Unseen Histories

In her book, A Revolution of Feeling, the writer Rachel Hewitt called the 1790s ‘the decade that forged the modern mind’. Your Laurence Jago series of crime novels is set during these years. Do you agree with Hewitt’s assessment?

Leonora Nattrass

Very much so. The debate over the French Revolution in Britain, along with the composition of the American Declaration of Independence twenty years earlier, established the basis for all our subsequent political discourse. Arguments over religion were replaced by the concept of ‘rights’ and began the serious discussion of extending the franchise which led to the Reform Act of 1832 and gradually thereafter to universal suffrage by 1928.

Unseen Histories

Does this make the 1790s particularly rich terrain for historical novelists?

Leonora Nattrass

think so! As I try to show through all my novels, Britain was gripped by a political paranoia among the ruling class that a similar revolution would happen here; while the sight of the popular participation in Paris encouraged a range of working-class radical groups which sprang up throughout Great Britain. My first novel, Black Drop, was based on the trial for High Treason of just such a group.

Unseen Histories

Scarlet Town is your third novel in this series and it is inspired by the true story of a contested local election. Can you tell us a little about this?

Leonora Nattrass

The novel is set in Laurence’s Cornish hometown of Helston, which was a ‘pocket borough’ – the particular pocket in this case being that of the Duke of Leeds, who told the electors how to vote! Due to a series of feuds and litigation in the town over the preceding twenty years, the ‘electorate’ had shrunk (in my novel) to two eighty-year-old men (in fact, in reality, there was only one!) An opposing group in the town set up a rival, larger, electorate who voted for two candidates of their own choosing and the resulting ‘double return’ went to Parliament to adjudicate between them.

Unseen Histories

The Georgian Age was both a time of huge political corruption and an age of early democratic progress. Looking back at it did you feel proud or horrified?

Leonora Nattrass

I’m not horrified – as L.P. Hartley says, ‘the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.’ Viewed on its own terms, the political system made sense, even if it was wildly out-of-date. There was a reason for Cornwall’s massive number of MPs (over 40!) since Cornwall, with its tin mines, had long been the industrial heart of the country. Now it was an anomaly since the emerging industrial centres of the north like Manchester and Leeds had no MPs at all.

Moreover, if one accepted that the vote should be based on ownership of property, then the voting qualifications only needed tweaking to make them reflect inflation.

But of course, from our present perspective of universal suffrage, it looks crazy. Especially egregious is the lack of a secret ballot with each voter announcing his vote in public and therefore subject to terrible intimidation.

Unseen Histories

Was politics at this time a male-only affair? Or could women play some part too?

Leonora Nattrass

It wasn’t just women that were excluded from politics. 95% of the population couldn’t vote! But, as I show in Scarlet Town, that didn’t stop everyone getting involved and passionate about the results of an election. Elite women held soirees where they invited politicians, and managed introductions between parties they thought should cooperate. Some acted as gatekeepers, managing who their M.P. fathers or husbands were ‘allowed’ to meet.

Some – most famously the Duchess of Devonshire – campaigned at the hustings. Meanwhile, large meetings of the voteless poor, as in Scarlet Town, could affect the votes of those who were enfranchised – and scare the authorities to death!

Unseen Histories

Your concern is not with Westminster but with a small town in West Cornwall. Did you find out how much people, in these distant outposts of the kingdom, cared about national politics? Or were their interests purely local ones?

Leonora Nattrass

The French Revolution and the conduct of the war were always of huge interest. And of course with Cornwall being a coastal county there were repeated scares about invasion as well as a keen interest in naval affairs. Falmouth was the main port for America and the great and good would constantly have been passing through. But in Scarlet Town, most of the animus is personal, between rival groups in Helston trying to get ahead.

In the 1790s laudanum was the only real panacea for pain and suffering. There were no general anaesthetics and surgery had to be fast and brutal. A good surgeon could take off a leg in ten seconds.

Unseen Histories

Medicine plays a significant role in your plot. The 1790s was a heady time of medical enquiry – one thinks of that brilliant Cornishman Humphry Davy and his experiments with nitrous oxide – can you tell us a little about developments in medicine at this time?

Leonora Nattrass

They were very few! In 1796, the year of my novel, the first inoculation against smallpox was performed: a development that would go on to transform the world. But germ theory didn’t emerge until the 1860s and at this time there were scarcely any effective drugs. A third of children died before the age of ten and the treatment of their ailments was hampered by the lack of antibiotics – a lack only remedied in the mid twentieth century, and when my mother contracted scarlet fever in the early 1930s she could easily have died. In the 1790s laudanum was the only real panacea for pain and suffering. There were no general anaesthetics and surgery had to be fast and brutal. A good surgeon could take off a leg in ten seconds.

Unseen Histories

The specific year of your story, 1796, is a loaded one in British history. The war with France will soon expand and become perilous as Napoleon’s power develops. Does this colour the atmosphere of your novel?

Leonora Nattrass

Jitteriness among the authorities and excitement among the masses – that’s the febrile atmosphere that makes the 1790s as a whole so very beguiling! 𖡹

Her first novel, Black Drop, was a Times Book of the Year and her second, Blue Water, was a Waterstones Thriller of the Month and long-listed for the Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year Award and the CWA Historical Dagger.

Scarlet Town

Viper, 5 October, 2023

RRP: £16.99 | ISBN: 978-1800816961

"An elegant, richly detailed, historical joy"

– Kate Griffin

1796. A rigged election. A town at war. A murderer at large...

Disgraced former Foreign Office clerk Laurence Jago and his larger-than-life employer the journalist William Philpott have escaped America - and Philpott's near imprisonment for libel - by the skin of their teeth. They return to Laurence's home town of Helston, Cornwall, in the hope of rest and recuperation, but instead find themselves in the middle of a tumultuous election that has the inhabitants of the town at one another's throats.

Only two men may vote in this rotten borough, and when one of them dies in suspicious circumstances, Laurence is ordered to investigate on behalf of the town's patron, his old master the Duke of Leeds. But it is no easy matter, thanks to the machinations of the rival political factions, not to mention the riotous performances of Toby the Sapient Hog.

Then the second elector is poisoned and suspicion turns on the town doctor, the gentle Pythagoras Jago, Laurence's own cousin. Suddenly Laurence finds himself ensnared in generations of bad blood and petty rivalries, with his cousin's fate in his hands...

"A wonderful and compelling murder mystery"

– Louise Fein

"A brilliantly entertaining historical crime caper"

– Philippa East

With thanks to Sophie Portas