Excerpt: Eavesdropping on the Enemy

The Man Who Saved MI6

Col. Thomas Kendrick was central to the British Secret Service from its beginnings through to the Second World War. Under the guise of "British Passport Officer", he ran spy networks across Europe and facilitated the escape of Austrian Jews. Bestselling author Helen Fry explores the private and public sides of Kendrick, revealing him to be the epitome of the "English gent"―easily able to charm those around him and scrupulously secretive.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Helen Fry

Thomas Kendrick lived for over 40 years in the shadows of the British Secret Service. He left no unpublished memoirs, his private papers were destroyed after his death and there were no obituaries in the British national newspapers. Only the men in trench coats and trilby hats – colleagues from MI6 – attending his funeral in a leafy suburb south of London in 1972 had any idea of his true contribution to history.

Dubbed ‘the elusive Englishman’ by Hitler’s Intelligence Service in the 1930s, Kendrick’s real identity eluded the Gestapo until betrayed by a double agent. Kendrick survived at the hands of Hitler’s henchmen and was expelled spying. He arrived back in London and disappeared from the public eye, but not from the ranks of the British Secret Service. He re-emerged during the Second World War to become MI6’s spymaster-in-chief against Nazi Germany, operating the longest deception and espionage programme from three clandestine sites.

It was an intelligence operation that shortened the war and saved millions of lives. After over 20 years of painstaking research and interviews, I was determined that he should not be forgotten. I am proud that his incredible legacy finally emerges from the shadows of secrecy. — Helen Fry

Eavesdropping on the Enemy

An abridged excerpt from Spymaster: The Man Who Saved MI6

he prospect of a swift end to the war via a military coup by a clique of Hitler’s generals had turned out to be a ruse by the Abwehr that targeted SIS. Kendrick was astute enough to know that the long, slow intelligence game was now Britain’s only hope of eventually defeating Nazi Germany. Experience had taught him that battles are won by intelligence and the quality of intelligence. His unique knowledge of Germany and his understanding of German psychology since the First World War, as well as his experience of Nazi Germany in the 1930s from his years in Vienna, made him a highly experienced and successful intelligence officer. His foresight in understanding that his new eavesdropping unit could produce intelligence capable of substantially altering the course of the war, and his expertise and determination in turning the M Room ['Mike' Room] project into a major intelligence-gathering operation, arguably saved MI6 in the end.

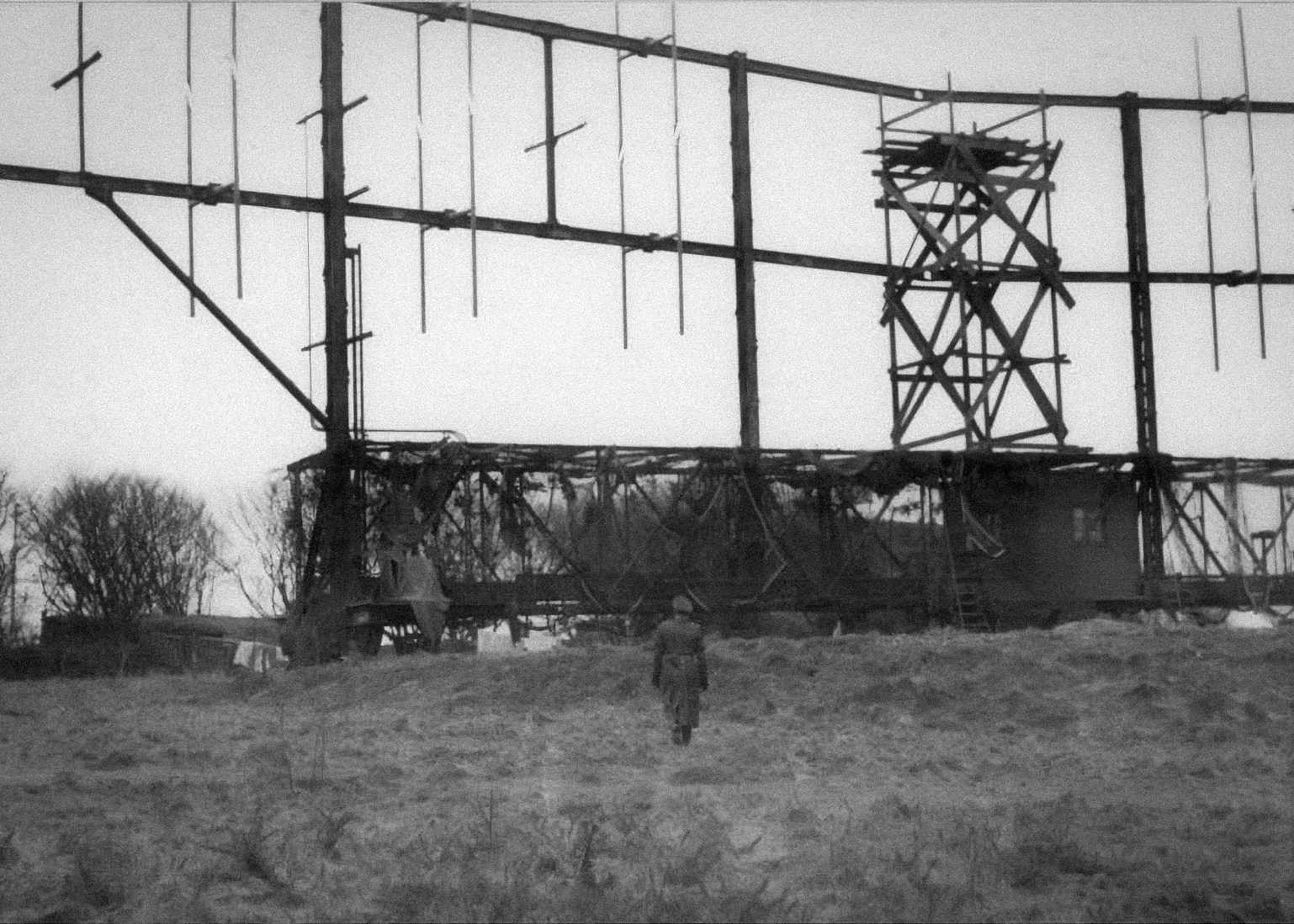

From October 1939, Kendrick focused on substantially increasing the bugging programme and making the site at Trent Park fit for purpose.[1] A specialist team from Dollis Hill Research Station installed state-of-the-art eavesdropping equipment in five interrogation rooms and six bedrooms in the mansion house, as well as in rooms in the stable block. This work took five months to complete.[2] The installation team was required to sign the Official Secrets Act, and Kendrick witnessed and countersigned the declarations. False panels and double ceilings were installed inside the house, in part to help with the soundproofing. Tiny microphones were concealed in the fireplaces and light fittings, with the wiring well concealed behind the wall panels and skirting boards. Temporary buildings were erected next to the main house, to accommodate interrogation rooms and an M Room.

The operation was dramatically scaled up as Kendrick increased his staff to just over 500, a third of them women.[3] This marked the beginning of a highly efficient, methodical intelligence-gathering ‘factory’ organized by Kendrick. He kept a tight rein on it, and it was no coincidence that his office was set up in the Blue Room of the mansion house – directly above one of the M Rooms. On his desk he had special equipment that enabled him to plug into any of the bugged bedrooms and interrogation rooms and to listen in via headphones or on a loudspeaker. The scale of the operation that was beginning to unfold is staggering. Kendrick – the spymaster – was orchestrating a superbly efficient spy network – targeted at the enemy, but on British soil.

Technology and HUMINT

Between January 1940 and the spring of 1942, over 3,000 German and Italian POWs were processed through Trent Park; at this stage in the war, the majority comprised Luftwaffe officers and U-boat crew. It became one of the most successful and far-reaching technology-driven HUMINT [Human Intelligence] deception operations in the Second World War.

A prisoner expected to be interrogated after capture; but, as Kendrick discovered, this was most fruitful when used in conjunction with the listening operation and stool pigeons. As he wrote in a memorandum to Norman Crockatt (head of MI9):

Whilst direct interrogation may provide valuable information it cannot, as a general rule, reasonably be expected to provide the same insight into the prisoner’s mind as is possible by the proper use of the listening method, which in addition to providing independent intelligence, often provides the interrogators with a check on statements made to them.[4]

It was his foresight in combining the three techniques – interrogation, stool pigeons and hidden microphones – that made the operation as an extraordinary success story.[5]

The state-of-the-art microphones used could pick up even a whispered conversation between prisoners, as former intelligence officer Catherine Townshend recalled:

After an extensive examination of the walls, floor and furniture of his room, a senior prisoner was heard to say to his cellmate: ‘There are no microphones here.’ But for safety’s sake the two men decided that they could converse more freely if they leant far out of the window. Little did they suspect that in addition to a minute microphone attached to the ceiling light fixture, another was hidden in the outside wall beneath the window sill.[6]

The authorities always tried to ensure that prisoners shared a room with someone carefully selected. Thus, back in their cells after interrogation, each man would begin to discuss the war with his cellmate – and often mentioned new technology being employed by the German navy or air force. Idle chatter by prisoners before interrogation offered the interrogators advance warning of what a prisoner might know and could be trying to withhold from them. After interrogation, a prisoner would often boast to his cellmate what he had not revealed. Kendrick reported that the attitude of prisoners who were security conscious could be broken down ‘by careful grouping of POWs and by devising ways and means of disarming suspicion’.[7] He held a weekly conference with the operations staff, and this proved extremely useful in promoting discussion of ways in which the modus operandi could be adapted to the changing intelligence needs of the day. He also issued a ‘Weekly Personal Report’, but these appear not to have been declassified into the National Archives.[8]

It was U-boat personnel, as early as January 1940, who gave Kendrick’s unit one of its earliest intelligence coups of the war, when they revealed secrets about German naval Enigma. This was to have a direct impact on the work at Bletchley Park, and is a good example of where a bugged conversation had a direct impact operationally.[9] The information came from U-boat Petty Officer Erich May of U-35, a U-boat that had been scuttled at the end of November 1939.[10] May proved so valuable to British intelligence that he was still being held at Trent Park in January 1940.[11] Naval interrogator Richard Pennell (RNVR) gained the trust of May to such an extent that the latter began to discuss with him how German naval Enigma worked.[12]

He provided valuable information on naval codes and short signals, which confirmed that the German navy spelt out numerals in full, instead of using the top row of a keyboard.[13] The transcripts of conversations between May and Pennell, which had been recorded in the M Room, were sent direct to Bletchley Park’s head, Commander Alastair Denniston, and to his cryptographers, Dilly Knox, Oliver Strachey and Frank Birch. The information was passed to Alan Turing and, as a result, he looked again at the German encryption for 28 November 1938 and came to the conclusion that British analysis of it had been fundamentally correct, provided the numerals were spelt out.[14] He and his colleagues turned to the unbroken cribs of shortly before December 1938 and, based on the new intelligence from Trent Park, they were able to break the code within a fortnight.

Intelligence from Enemy POWs

The intelligence gathered by the combined services unit became increasingly detailed and of much greater significance. CSDIC [Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre] disseminated vast quantities of information and snippets of intelligence about the enemy to those departments that needed to see it – from MI5, MI6 and MI14 to the War Office, Bomber Command, the Air Ministry, the Admiralty and – eventually, once the United States entered the war in December 1941 – to US intelligence. Kendrick’s first intelligence summary of the unit’s work, which covered September 1939 to December 1940, demonstrates the extensive and detailed information about Germany’s military capabilities that was being harvested by eavesdropping on prisoners’ conversations.[15] The subjects included aerodromes in German-occupied countries, artillery, enemy aircraft equipment and navigational technology, the Gestapo, conditions in Germany, hand grenades, identification of German units and aircraft production, German paratroopers, Poland, rockets, weapons and torpedoes, U-boat movements and tactics, tanks, Jews, the SS and the strength of enemy armed forces.[16] Information had been gained on U-boat operations around Norway between April and June 1940, as well as on British submarines in the region – essential for assessing how much the Germans knew about British naval operations.[17]

Major General Francis H. Davidson, the new director of military intelligence, was impressed by Kendrick’s first report, commenting: ‘The general spirit of this Survey (and the weekly reports) shows the true spirit of attacking intelligence.’[18]

Airmen POWs not infrequently alluded in their conversations to technology on board their aircraft – often ‘a considerable time before the emergence of such a weapon in operations’.[19] In February 1940, the microphones picked up the first mentions of new technology being used by the Luftwaffe, called X-Gerät and Knickebein.[20] The system functioned like an early radar system, enabling German pilots to conduct more precise bombing raids across Britain. It was the first inkling that British intelligence had of this new technology. Armed with information about X-Gerät from the special recordings, the Air Ministry was able to build a profile of the German war capability and to develop counter-technology.[21] As Professor R.V. Jones, scientific adviser to MI6, confirmed, the British countermeasures resulted in the deflection of many bombs from their intended targets. Kendrick’s close friend and colleague Denys Felkin (head of air intelligence at Trent Park) concluded that the discovery of the existence of X-Gerät and Knickebein had ‘the most far-reaching consequences... [The developments were] reported in time for the British authorities to prepare countermeasures against a method of bombing which in the autumn of 1940 constituted a very real threat to British war industries.’[22] It gave Britain time to improve its defences, so that the German air force had to find new ways of attacking. The uncovering of X-Gerät and Knickebein was so critical that Norman Crockatt, head of MI9, wrote to Kendrick to congratulate him and ‘those officers under you who contributed so largely to one of the most successful pieces of intelligence investigation I have ever come across’.[23] Crockatt later reported that: ‘The secret recordings produced some of the earliest information of the German experiments in Air Navigational aids [March 1940], and has played an important part in the successful development of the British counter- measures.’[24] German radar devices – both land and airborne – continued to be reported by prisoners throughout the war, in many cases ahead of their appearance in the various theatres of battle.

All transcripts of conversations and interrogations were filed in a newly compiled index library, so that if a particular subject became relevant or urgent as the war progressed, the appropriate transcripts could be pulled from the filing cabinets and consulted. To gauge the usefulness or otherwise of the recorded conversations, Kendrick sent a questionnaire to the intelligence departments. The response from Admiral John Godfrey, head of naval intelligence, was telling:

Without them [the Special Reports] it would have been impossible to piece together the histories of [enemy] ships, their activities and the tactics employed by U-boats in attacking convoys. The hardest naval information to obtain with any degree of reliability concerned technical matters . . . I wish to convey to the staff at the CSDIC my warm appreciation of their work.[25]

Stewart Menzies, ‘C’, reinforced the importance of the work from the MI6 angle:

The reports are of distinct value, and I trust the work will be maintained and every possible assistance given to the Centre [CSDIC]. It is essential that the Service Departments should collaborate closely by providing Kendrick with the latest questionnaires, without which he must be working largely in the dark.[26]

The expansion of the bugging operation was proving successful. At moments of crisis in this war, Kendrick could be relied upon to deliver intelligence. He was confident in his methods, because he understood the prisoners: he understood human nature and how best to secure information. While it is true that the thousands of transcripts emanating from Trent Park offered screeds of information in piecemeal form, this could be used to corroborate intelligence coming in from other sources.

The unit’s work was so valuable to the outcome of the war that its existence had to be heavily protected. Charles Deveson, an intelligence officer, recalled that on his first day he was called into Kendrick’s office and ordered to sign the Official Secrets Act.[27] Kendrick slid a pistol across the desk and looked Deveson straight in the eye: ‘If you ever betray anything about this work, here is the gun with which I expect you to do the decent thing. If you don’t, I will.’[28]

Though a jovial military commander, who on the surface seemed like an amiable grandfather, Kendrick had a serious side – a deadly side that meant he would kill to protect his country. Betrayal of this operation had only one possible ending.

The Battle of Britain

The fall of Norway and Denmark in April 1940 to the German invading forces, and of the Low Countries and France in May 1940, left Britain standing alone against Nazi Germany. Now more than ever, it was up to Kendrick’s unit to harvest intelligence in an effort to keep ahead in the war. Central to this was intelligence on the Luftwaffe, new technology and fighter tactics. Britain had to retain air superiority over the Luftwaffe in order to avert an invasion of its shores by Hitler’s forces under cover of German aircraft. It is no exaggeration to say that the Battle of Britain, fought from July 1940 to October 1940, was a fight for survival. The conversations of Axis prisoners at this time were peppered with information on new aircraft being developed in Germany, including details of the new Focke-Wulf fighters, gleaned from German pilots shot down in the Battle of Britain:[29]

Prisoner A: The Focke-Wulf fighters ought to be out.

Prisoner B: We have been told they are already on their way, these birds – 700 or 720 [km/hour] cruising speed – at any rate, according to a friend of mine who has flown them.[30]

Those prisoners had just provided details of a new German aircraft in development and being tested, including details of its capability.

Other prisoners continued to talk about losses, as in the case of Prisoner A427 (true name unknown), who commented to his cellmate: ‘Only five out of eight of our aircraft come back... We are losing too many aircraft... We have lost our best airmen.’[31] Such snippets of information were analysed by the British in an attempt to gauge the true losses of German aircraft and fighting capability.

There were eyewitness accounts of the Battle of Britain from the enemy perspective, as it was happening. On 2 September 1940, two prisoners being held at Trent Park watched a dogfight overhead between German aircraft and British Spitfires. Their bugged conversation captured a moment when the battle was actually taking place:

Prisoner B: You can see it from here, a Spitfire up there. Just there – underneath. It has flown in a sort of arc. There it comes again over here.

Prisoner A: Oh! There is a Zerstörer [heavy fighter] (More M.G. [machine- gun] fire and roaring of engines is heard). There it is again, the Spitfire, always following up.

Prisoner B: Yes!

Prisoner A: It seems to be coming down [the German ME 110]. It’s already on fire.

Prisoner B: Now he’s dropping incendiary bombs. Prisoner A: Now you can see how fast it is [the Spitfire].[32]

Today, the transcripts are historically significant, as they preserve rare conversations of the Second World War and eyewitness accounts of the war from an enemy perspective. The dialogues are very natural and human: at one point Prisoner A437 described to his cellmate how, after capture, he had been given a really good meal of fried eggs and bacon, toast, jam and butter. His cellmate piped up: ‘Well, you don’t get a meal like that in the whole of our armed forces.’[33]

During 1940, most prisoners expected the invasion to be imminent. But by 1941, their hopes had waned and they were increasingly sceptical that there would be any invasion of England at all. Even so, there could be no let-up in the intelligence gathering. The eavesdropping programme continued throughout 1941, with prisoners starting to speak about the heavy U-boat losses suffered. The surviving crew from the Admiral Graf Spee and the warship Gneisenau were brought to Trent Park, where they were monitored discussing the movements and tactics of their vessels. They also spoke about the German battleship Scharnhorst – the same ship whose construction in the 1930s had so interested Kendrick’s agents dispatched from Vienna. Survivors of the Bismarck described its last voyage in considerable detail, including the damage inflicted on it by HMS Hood and HMS Prince of Wales. In all, 110 survivors were picked up (from a crew of 2,200) and brought to Trent Park. In their unguarded conversations, German seamen gave away the names of shipyards, their locations on the Baltic coast and details of their production of new U-boats and warships.[34] Some shipyards were already known to the British, such as Kiel and Wilhelmshaven – facilities that remained as important to Kendrick’s intelligence work as they had been in the 1930s.

The most intense battles were being fought at sea, and vital information about the Battle of the Atlantic was being harvested from prisoners of war passing through Kendrick’s site.[35] On technical matters, the most important naval information for this period was the development of a new magnetically fused torpedo.[36]

From Trent Park came the first confirmation that Hitler was shifting his focus away from invasion to a marine campaign and blockade of supplies into Britain.[37] It was vital for British commanders to anticipate the enemy’s next move if they were to maintain supremacy of the seas through difficult battles that would last most of the war. For that, intelligence was needed – and a major source was the M Room transcripts. Kendrick believed that Britain would win the intelligence war. But Trent Park was to prove inadequate to deal with the thousands of German prisoners who would be captured on the battlefields and at sea. In response, Kendrick scaled up his operations and expanded capacity yet further.

Secret Houses

In early 1941, Kendrick requisitioned Latimer House, near Chesham, and Wilton Park at Beaconsfield, in Buckinghamshire. The sites were chosen because they were secluded and yet were within easy reach of London, only some 25–30 miles away. So valuable for the war effort was the intelligence that had already been generated at Trent Park that the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee (JIC) in London authorized an unlimited budget for Kendrick to make Latimer House and Wilton Park operational. It concluded that Kendrick’s unit was:

Of the utmost operational importance, vital to the needs of the three fighting services and should accordingly be given the highest degree of priority in all its requirements; that the normal formalities regarding surveys, plans and tenders should be waived and that any work required should be put in hand at once and completed by the earliest possible date irrespective of cost.[38]

This endorsement was signed by, among others, Stewart Menzies (‘C’), John Godfrey (head of naval intelligence) and Francis Davidson (director of military intelligence).

A declassified memo (marked ‘To be Kept under Lock and Key’) indicates the cost involved in expanding to these two sites: £400,000 (roughly £25 million today).[39] This involved the construction of a complex of temporary prefabricated buildings at both sites, known as the ‘Spider’. It consisted of cells, an interrogation and administration block, M Room, a cookhouse, guard block and Nissen huts in the grounds. The rooms were fitted with bugging devices and wired to M Room. Kendrick increased his complement of staff across the sites to 967 army personnel (intelligence and non-intelligence);[40] the naval intelligence team there was expanded by Ian Fleming.[41] Within the year, Fleming himself had moved to Buckinghamshire to train his 30 Assault Unit at nearby Shardeloes House, Amersham. He was a frequent visitor to Latimer House and was photographed with the naval intelligence team on site and at a drinks party on the balcony of the mansion house.

While construction continued at Latimer House and Wilton Park, Kendrick received a telephone call from his boss, ‘C’. Kendrick’s war was about to take an unexpected turn as he, with two other SIS officers – Frank Foley and a certain ‘Captain R. Barnes’ (whose identify has never been revealed) – was about to take charge of the most prized and highest-ranking German prisoner ever to be held in Britain ■

1. Two prisoner of war camps were located on the Trent Park estate, known as No. 1 POW Camp and No. 2 POW Camp, both directly under the auspices of British intelligence. One camp was based in the mansion house and stable block, and the other nearby at Ludgrove Hall (still on the estate). 'Minutes of Meeting held in the War Office, February 21, 1940, WO 208/3458. It is believed that the camp at Ludgrove Hall came under the command of Kendrick's colleague Colonel Alexander Scotland. This camp became known as the London Cage and in 1940 relocated to Kensington Palace Gardens; see Fry, The London Cage.

2. The equipment was supplied by the Radio Corporation of America: Inventory of Equipment Supplied and Installed at Cockfosters Camp', WO 208/3457. See also 'Installation and Use of Microphones at CSDIC (UK) P/W Camps 1939-1945, appendix G of The History of CSDIC', WO 208/4970.

3. Burton Scott Rivers Cope joined the naval intelligence section at Trent Park and headed it from March 1940. See the Trench diary, 12 March 1940; Derek Nudd, Castaways of the Kriegsmarine: How shipwrecked German seamen helped the Allies win the Second World War, Createspace, 2017, pp. 61-70; and Fry, The Walls Have Ears, pp. 48-51. The naval intelligence section staff were recruited by lan Fleming of naval intelligence. The air intelligence section, ADI(K), had moved to Trent Park in mid-December 1939. The daily administration and security of the site shortly transferred from Major (Count) Anthony de Salis to the command of Major Topham. 'Minutes of Meeting held in the War Office, February 21, 1940', WO 208/3458.

4. See also 'The History of CSDIC', p.6 and appendix F (section 9), WO 208/4970.

5. Kendrick's report, 22 July 1941, WO 3455.

6. Catherine Jestin, A War Bride's Story, privately published, p. 229.

7. Kendrick's report, 22 July 1941, WO 208/3455.

8. Reference to Kendrick's 'Weekly Personal Reports' in Norman Crockatt's memo, 25 July 1941, WO 208/3455.

9. For more detailed study of the intelligence given by May to Pennell about German Enigma and codes, see Fry, The Walls Have Ears, pp. 34-35.

10. Trench diary, 30 November 1939 and 4 December 1939.

11. Erich May's incarceration, first at the Tower and then at Trent Park, triggered the first known meeting, on 28 December 1939, between Alastair Denniston, the first head of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, and Bernard Trench, a naval interrogator working between the Admiralty and Trent Park.

12. Interrogation reports, 8 January 1940 and 19 January 1940, WO 208/5158.

13. "The History of Hut Eight', p. 24, HW 25/2.

14. ibid., pp. 24-25. Turing looked again at the German 'Forty Weepy Cribs' encryption. He and his colleagues noticed that two new wheels had been added to the naval Enigma machines by the Germans in December 1938 and so it had not been possible to trace the 'Forty Weepy' encryption messages, as call signs were no longer being used. They worked on them again in January 1940, using the knowledge they now had from prisoner Erich May. A further four days of cribs were broken on the same wheel order. For an explanation of the "Forty Weepy Cribs', see Christof Teuscher, Alan Turing: Life and legacy of a great thinker, Springer, 2005, p. 455.

15. 'CSDIC Survey 3 September 1939 to 31 December 1940', WO 208/3455. Copy also in WO 208/4970.

16. ibid. See also minute NID 01789/39, 1 August 1940, ADM 1/23905.

17. Trench diary, entries for 25 May 1940 and 17 June 1940.

18. Davidson's comments in Appendix B, MI9a/683, WO 208/4970.

19. 'Intelligence from Prisoners of War', report by Felkin, section 26, AIR 40/2636.

20. SRA 37, 27 February 1940, AIR 40/3455.

21. R.V. Jones, Most Secret War, Coronet, 1978, pp. 234-36. The significance of this intelligence is discussed further in Fry, The Walls Have Ears.

22. 'Intelligence from Prisoners of War', report by Felkin, section 117, AIR 40/2636.

23. Letter from Crockatt to Kendrick, 10 April 1940, in the Kendrick archive.

24. Minute dated 25 July 1941, WO 208/3455.

25. Letter dated 11 February 1941, WO 208/3460.

26. Letter dated 21 February 1941, Stewart Menzies (head of MIG) to Crockatt, WO 208/4970.

27. Charles Deveson was born in London in 1910, studied English at the University of Oxford, then taught at an exclusive boys' boarding school in Prussia. He returned to England in 1936. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, he enlisted in the Royal Armoured Corps, and by 1941 had transferred to the Intelligence Corps.

28. Author's interview with Richard Deveson.

29. See, for example, SRA 305, 10 August 1940; SRA 441, 2 September 1940; and SRA 498, 11 September 1940, AIR 40/3070.

30. SRA 441, 2 September 1940, AIR 40/3070.

31. SRA 495, 10 September 1940, AIR 40/3070.

32. SRA441, 2 September 1940, AIR 40/3070.

33. ibid.

34. SRX 10, 26 December 1939, WO 208/4158.

35. POWs came from the Bismarck, Alstertor, Gonzenheim, Egerland, Lothringen and the prize ship Ketty Brövig. Also from Raider 35 (Pinguin) and Raider 16, as well as the following U-boats: U-651, U-138, U-556, U-570, U-501, U-111, U-95, U-433 and U-574. For bugged conversations from the survivors, see, for example, SRN 574, 22 July 1941, SRN 575, 20 July 1941, SRN 576, 22 July 1941, WO 208/4143.

36. Fry, The Walls Have Ears, p. 49.

37. 'CSDIC Half-Yearly Survey: 1 January 1941 to 30 June 1941', WO 208/3455

38. 40. 17 February 1941, CAB 79/9/19. See also 'Accommodation for CDIC, p. 1, WO 208/3456. Copy also in WO 208/5621.

39. Memorandum, 7 October 1941, CAB 121/236. See also Interference with the work of CSDIC by the Construction of the Aerodrome at Bovingdon', WO 208/3456.

40. Army intelligence staff numbered 156; the naval intelligence section consisted of 10 officers, including five WRNS, four non-commissioned WRNS and six captured German naval officers who assisted the interrogation as collaborators; and the air intelligence section numbered just over 100. There were also warders, guards, cooks, signals specialists, couriers, a barber, medical officer and site maintenance personnel.

41. The naval intelligence team included Ralph Izard (formerly of the Daily MaiN, John Mariner (Reuters), John Everett, John Connell, Charles Wheeler, Colin McFadyean and Czech refugee Harry Scholar. The female naval intelligence officers included Evelyn Barron, Esme McKenzie, Jean Flowers, Celia Thomas Ruth Hales and Gwen Neal-Wall

Spymaster: The Man Who Saved MI6

Yale University Press, 12 October 2021

RRP: £20.00 | 320pages | ISBN: 978-0300255959

The dramatic story of a man who stood at the center of British intelligence operations, the ultimate spymaster of World War II: Thomas Kendrick

Thomas Kendrick (1881–1972) was central to the British Secret Service from its beginnings through to the Second World War. Under the guise of “British Passport Officer,” he ran spy networks across Europe, facilitated the escape of Austrian Jews, and later went on to set up the “M Room,” a listening operation which elicited information of the same significance and scope as Bletchley Park. Yet the work of Kendrick, and its full significance, remained largely unknown.

Helen Fry draws on extensive original research to tell the story of this remarkable British intelligence officer. Kendrick’s life sheds light on the development of MI6 itself—he was one of the few men to serve Britain across three wars, two of which while working for the British Secret Service. Fry explores the private and public sides of Kendrick, revealing him to be the epitome of the “English gent”—easily able to charm those around him and scrupulously secretive.

“A remarkable piece of historical detective work. . . . Now, thanks to this groundbreaking book, the result of years of meticulous research and expert analysis, Kendrick’s role as one of the great spymasters of the twentieth century can be revealed.”— Saul David, Daily Telegraph

"Fry has done a remarkable job of reconstructing the life, networks and secrets of a man who spent most of his existence hiding them."

– James Own, The Times

Helen recommends:

⇲ Secret Service: The Making Of The British Intelligence Community by Christopher Andrew (Sceptre Books, 1987)

⇲ The Walls Have Ears: The Greatest Intelligence Operation of World War II by Helen Fry (Yale University Press, October 2020)

⇲ MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949 by Keith Jeffery (Bloomsbury January, 2010)

⇲ A Life in Secrets: Vera Atkins and the Missing Agents of WWII by Sarah Helm (Anchor; First Anchor Books E edition, December, 2007)

⇲ Hitler's Generals in America: Nazi POWs and Allied Military Intelligence by Derek Mallett (University Press Audiobooks, September 2017)

⇲ Tapping Hitler’s Generals: Transcripts of Secret Conversations 1942-45 by Sönke Neitzel (Frontline Books, July 2013)

⇲ The Secrets of Station X: How the Bletchley Park codebreakers helped win the War by Michael Smith (Biteback Publishing, October 2011)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Chloe Foster and Yale University Press. Author photograph © Greg Morrison.