Stones of Empire

Catherine Fletcher reflects upon travellers' tales and political spaces as she follows Europe's Roman roads

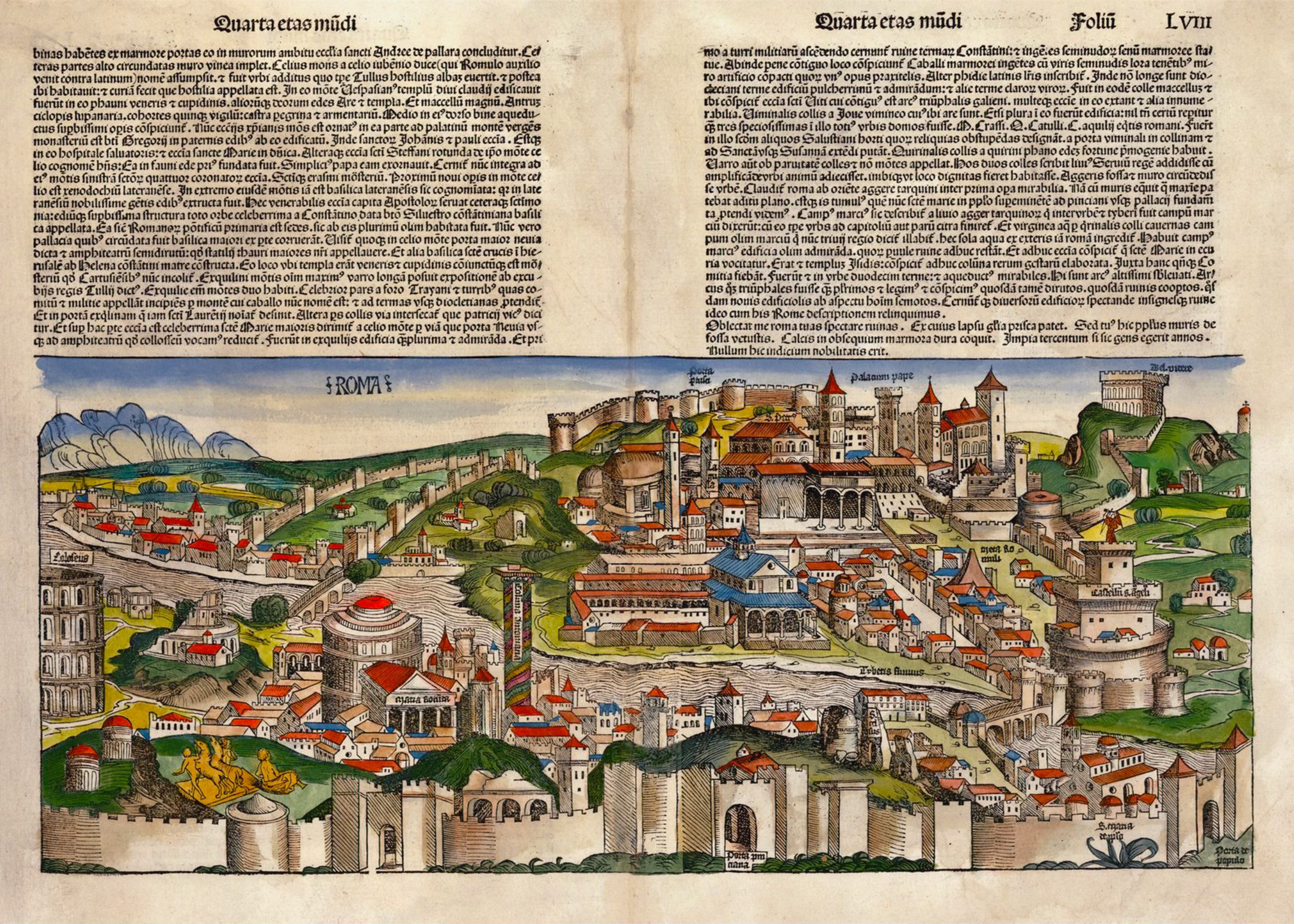

There is something certain and reliable in our conception of a Roman road. These great arteries of travel and trade knitted together the ancient world and the remains of many of them survive to this day.

Several years ago the historian Catherine Fletcher set out to investigate the cultural history of these roads.

For Fletcher, however, as for so many others over the centuries, her travels along the Via Appia and Via Agrigento would be both disrupted and provoking.

Twenty years ago, I was working on the research that eventually became my first book. Our Man in Rome was a study of King Henry VIII's six years of negotiation to end his marriage to Catherine of Aragon.

It took a fortnight to get from London to Rome in the sixteenth century, if you were lucky, a speed similar to those achieved by the ancient Romans. Henry's ambassadors took much the same routes as the invaders of Britain had fifteen hundred years before. I was interested in how they travelled, how the roads and the inns along the way became spaces for political activity.

Travelling to Rome was already a part of my own life. I first visited the city in 2001, for an Italian course. Where was I on 9/11? Rome. At the airport, in fact, just off the Via Appia.

Ciampino was the cheap airport, cheap enough that the TVs weren't showing rolling news pictures, just updates in plain text. My language school had equipped me with sufficient vocabulary to translate the words 'torri gemelle': twin towers.

My plane home to London must have been one of the last out before restrictions kicked in. I only saw the pictures after I landed, when I got on the train to Liverpool Street and picked up someone's abandoned newspaper.

Thus I, like every traveller to Rome, have a story. Over the years, as I returned to the city to research and to live, I acquired more tales, if rarely so dramatic. At the start of 2020, I suggested to my agent that the history of travel to Rome might make a good subject for a book. She agreed, and I booked my first research trip.

I would walk across Sicily on a Roman road, the Via Agrigento. This was scheduled for April. Then Covid-19 struck. My walks were constrained to an hour a day, to and from my Manchester flat.

I became an armchair traveller, reading accounts of roads ancient and modern, imagining how they might have looked as I sketched out a book proposal.

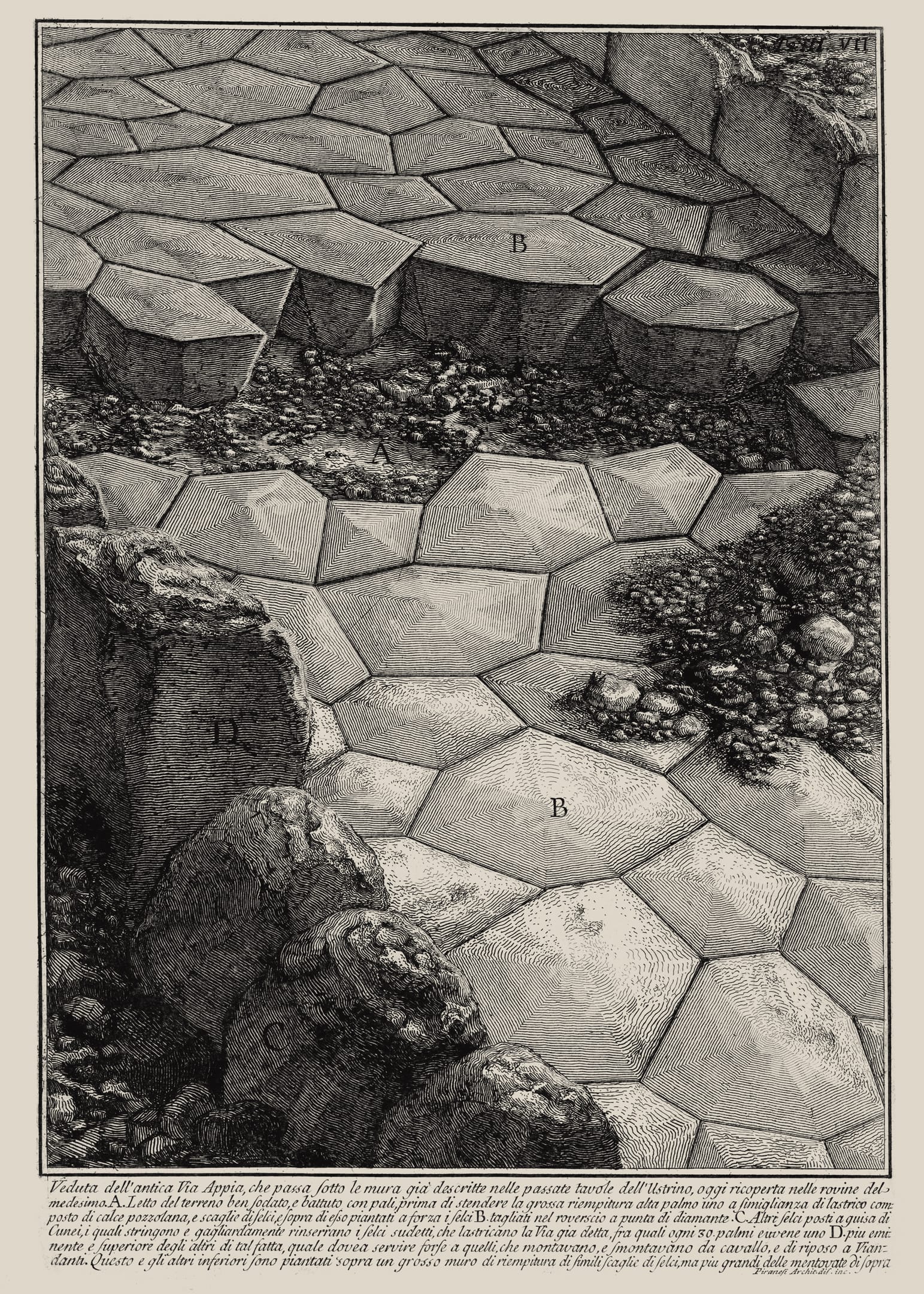

As I worked through the sources, I began to understand why Charles Dickens had written of the Via Appia that here is 'a history in every stone that strews the ground'.

In the spring of 2022, I tried a fortnight's trip. By this time, I'd ruled out attempting long walks. There was too much to do. Instead, I would go by train, visiting sections of Roman roads where they were visible.

I followed the itinerary shown on the Vicarello Cups, four ancient silver vessels in the shape of Roman milestones found in a Tuscan spa in 1852. They're engraved with lists of stops between Cádiz, on the southern coast of Spain, and Rome.

The Spanish section of this route is known as the Via Augusta, a street name still in use in Tarragona, the location of spectacular Roman remains including a seaside amphitheatre. Modern life wasn't yet quite normal, if it ever would be: on public transport we remained in masks, and in my Barcelona hotel a notice asked guests to bear with the changes required to welcome refugees from Ukraine.

It wasn't until November 2021 that I arrived in Rome, now in a world of masking and green passes. I spent sixty-four Swiss francs on a Covid test that no-one ever checked. It gave me some fellow feeling for the Grand Tourists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They were also required to pay to demonstrate their state of their own health, with paperwork that confirmed they were free from the plague.

One wily English traveller of the 1720s obtained two different certificates from the authorities in Ravenna: one to prove he was healthy, the other to confirm he was sick enough that he needed to eat meat during Lent.

That dry run accomplished, in autumn 2022 I bought an Interrail pass and set out on a two-month trip to explore the reaches of the Roman road network. I would go south, from Manchester through London to Paris, then beyond to Avignon and into Italy.

It was hot. On the London trees the leaves were yellowing; the train around the Mediterranean coast crossed river after dried-up river.

On my way out of Nice I heard that Liz Truss had been elected leader of the Conservative Party, taking over from Boris Johnson as Prime Minister. The Queen died. I headed cross-country to Rimini and from there south to Rome. At the British School the flag was flying at half-mast.

I rented a car and drove down the first, straight stretch of the Via Appia. Past its southern end, I stayed in a hotel converted from office buildings originally constructed for the Mostra d'Oltremare.

In 1937, this had been the Fascist regime's demonstration of its international power. I stayed there for two nights before the 2022 Italian elections. The hotel was very stylish. The hard right 'Brothers of Italy' party, led by Giorgia Meloni, won.

Heading back north to Rome a few days later, I stopped at the Frattocchie branch of McDonald's.

Beneath this restaurant are the remains of a Roman road, a side street off the Via Appia with some remarkably well-preserved paving. The economical fast-food pricing was a bonus: this was the day of the Truss government's ill-fated mini-budget, and sterling was slumping in my currency app.

In the second month of my trip, I amused myself by playing trader. Could anything in British politics produce a bounce in the value of the pound?

Occasionally, yes. When Truss quit, I was in Albania, at the end of the Via Egnatia that links Durrës via Thessaloniki to Istanbul. A currency bet paid my laundrette bill.

Still, that's a scenario that would have looked familiar to the Tudor ambassadors who got me into this. They too had to deal with a depreciating currency and a quite unfavourable geopolitical situation.

The roads to Rome are, in one sense, a timeless presence through the history of our continent, silent but pervasive stones of empire. Yet they're also a stage on which one story after another is played out, a setting for the continent's history •

This feature was originally published June 18, 2024.

Catherine is Professor of History at Manchester Metropolitan University and broadcasts regularly for the BBC.

The Roads To Rome: A Journey Into Europe’s Past

Vintage Publishing, 12 June, 2025

RRP: £12.99 | 9781529932690

“Epic and witty… Fletcher is a thoroughly enjoyable narrator” – The Observer

‘All roads lead to Rome.’ It's a medieval proverb, but it's also true: today's European roads still follow the networks of the ancient empire, stitching together our histories and continuing to inspire our imaginations.

Over the two thousand years since they were first built, the roads have been walked by crusaders and pilgrims, liberators and dictators, but also by tourists and writers, refugees and artists. As channels of trade and travel, and routes for conquest and creativity, Catherine Fletcher shows how the roads forever transformed the cultures, and intertwined the fates, of a vast panoply of people across Europe and beyond.

Reflecting on his own walk on the Appian Way, Charles Dickens observed that here is ‘a history in every stone that strews the ground.’ Based on outstanding original research, and brimming with life and drama, this is the first book to explore two thousand years of history through one of the greatest imperial networks ever built.

“Very readable ... these routes are almost a natural part of the landscape. The reader departs the book with a feeling that they have been there for an unimaginable time, travelled on by a cast of vivid characters. It is a compelling image, in an enjoyable book”

― Financial Times

With thanks to Susie Merry.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store