Surviving the Titanic

Frances Quinn finds a new story in the most famous shipwreck of all time

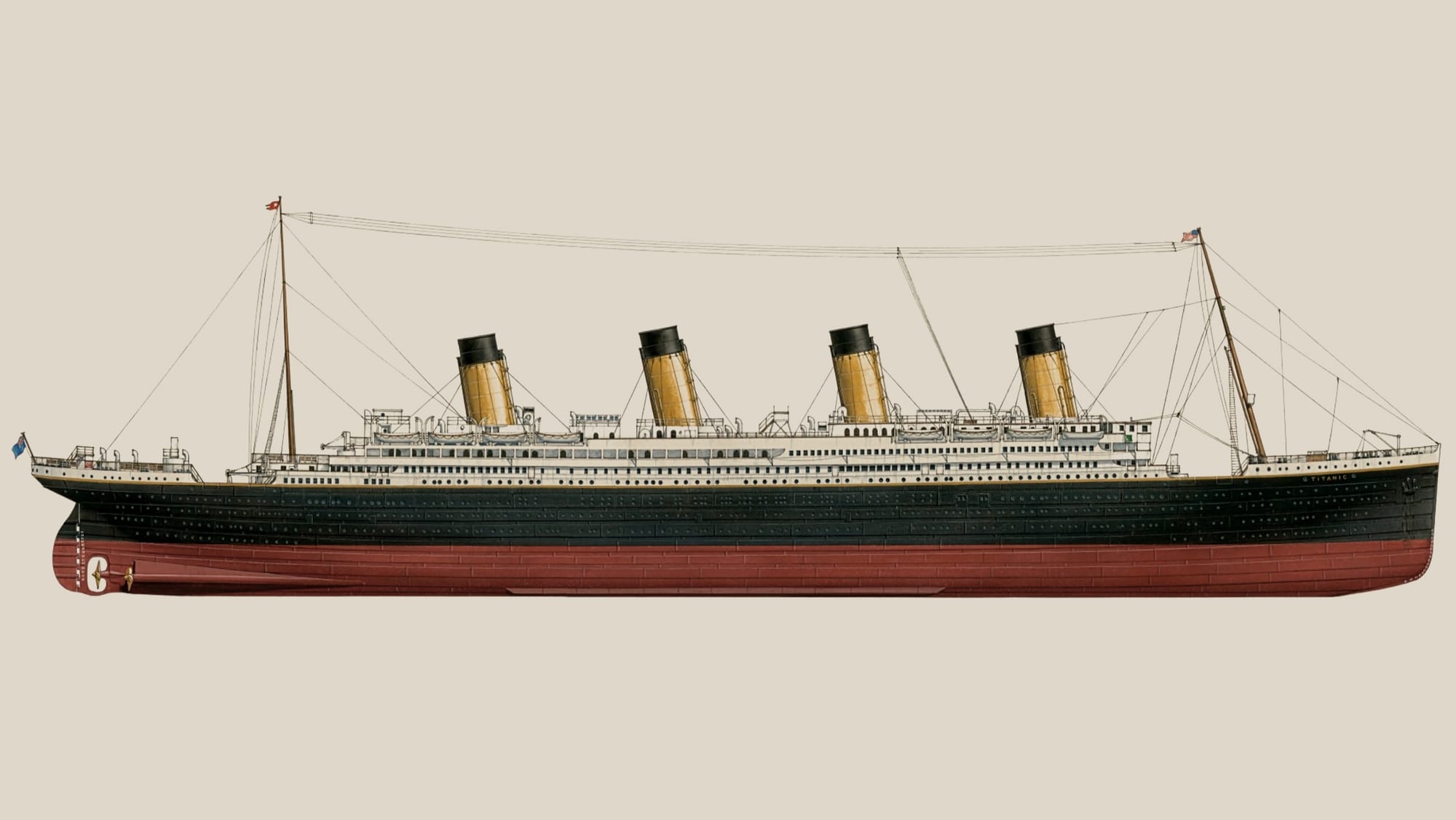

Our vision of the Titanic has been shaped and finessed over time. We are now instantly familiar with it: the slender beauty of the ship, the luxury of its fittings, the confidence of Captain Smith and the cold, glassy calm of the Atlantic Ocean.

All this, of course, combined in tragic fashion that night in April 1912 when the ship struck an iceberg and more than a thousand perished in a few anguished hours.

For her third novel, the writer Frances Quinn has been drawn back to this story. Researching it anew she confronted a traumatic event whose effects impacted lives long into the twentieth-century.

If I think back to when I first heard of the Titanic, it was probably on Blue Peter. That it was considered suitable for a kids' television programme tells you, straight away, just how deeply embedded this story is in popular culture.

It's as familiar as the Three Bears or Cinderella, and everyone knows how it goes: the unsinkable ship; the iceberg looming up in the night; the watertight compartments that weren't; the lack of lifeboats; the band that played on.

As a result, it's almost become light entertainment: Celine Dion singing My Heart Will Go On, and jokes about rearranging deckchairs. So when I started researching my novel, The Lost Passenger, I was unprepared for how traumatic it would be to read the stories of those who were there.

An estimated 2,240 people boarded the Titanic before it crossed the Atlantic, boarding in Southampton, Cherbourg and Queenstown in Ireland. Only 706 survived: 492 passengers and 214 crew. The rest perished: some, it's thought, trapped in the ship, but most in the water.

The sea temperature was -2.2 C, and recent medical research suggests they would have died from hypothermia, rather than drowning as claimed in the official report.

The horrible detail that struck me when I started researching my book was that the people who were saved, who made it to the lifeboats, could hear those in the icy sea crying out for help.

Almost every survivor’s story I read mentioned that they’d never forgotten that sound; one of the children who was rescued, Frank Goldsmith, lived near a baseball stadium, and through his whole life, the sound of the crowd brought back that night.

Many of the passengers sitting in the lifeboats, hearing the cries gradually die away as people succumbed to the cold, would have been women who’d had to leave behind husbands, fiancés, fathers and brothers when they left the ship.

Because of the maritime principle of ‘women and children first’, the vast majority of adults who made it to the lifeboats were women. But as they took their seats, most of them couldn’t have known that the ship didn’t have enough lifeboats for everyone.

When the first lifeboats went off, there was no panic, because passengers were assured a rescue ship would be near. They must have believed, as the heroine of The Lost Passenger, Elinor Coombes, does, that the men would follow later.

Lifeboats were still being let down even as the ship sank, so only when they watched its final moments and saw how many were still on board, would they have realised how very few men would be saved. As those cries rang out in the darkness, were they listening for familiar voices?

Certainly they would have known by then that it was very possible they were hearing their own loved ones beg for help from the freezing water. And when the rescue ship, Carpathia, finally arrived in New York, it would have been full of women who’d boarded the Titanic as wives, and reached the other side of the Atlantic as widows, as Elinor does.

It was reading those accounts that made me wonder, how do you get over something like that? What does it do to you as a person? People who’ve had a brush with death - whether through accident or illness - often say it changes their perspective on life. Some become more fearful, having seen their vulnerability, but many vow to make the best of the chance they’ve been given and grab life with both hands.

We don’t know the fates of all the women who survived. There must have been those who simply couldn’t cope. At least one woman survivor committed suicide; there were broken marriages, and many could never bear to speak of that night, even to their families. But of the handful of stories that have come down the years, it’s striking how many of the women seem to have made a conscious decision to live their lives purposefully.

Margaret Brown - often known as ‘unsinkable Molly Brown’ - established the Survivor’s Committee, raising almost $10,000 for those ruined by the disaster. Then, during and after World War I, she worked in France with the Red Cross organising female ambulance drivers, nurses, and food distributors, for which she was awarded the Legion of Honour.

There was also Elsie Bowerman who was among the first female barristers in England and served on the United Nations' Commission on the Status of Women. Another survivor was Edith Rosenbaum who became a war correspondent, reporting from the trenches in World War I.

Then there was Irene Harris who lost her theatre producer husband in the sinking, but took over his business in New York, becoming the first female producer on Broadway, backing or managing over 200 productions during her two-decade career.

One of the very youngest survivors, Eva Hart, became a professional singer, a magistrate and a political organiser, and during the Second World War, organised entertainment for the troops and distributed emergency supplies to people after The Blitz. She was awarded the MBE for ‘political and public services in London’.

All their feats were achieved in the shadow of terrible memories, perhaps even what these days we’d call PTSD: they would very probably have had flashbacks and nightmares, and a terror of water or travel by sea.

Eva Hart, for example, was plagued with nightmares and eventually confronted her fears by booking a ticket on a ship sailing to Singapore, where she locked herself in her cabin for four days. Theirs are stories of remarkable courage and resilience, of making the most of life after witnessing such a terrible tragedy.

In The Lost Passenger, on board the rescue ship Carpathia, Elinor has the kind of confrontation with herself that I imagine some of those women - and others whose stories we don’t know - must have had. ‘I sat there,’ she says,’ and I kept thinking of all those people begging for help in the darkness…We’d been given the chance to go on with our lives, when so many others had lost theirs.’

As a result, she makes the huge decision not to go back to her old life (you’ll need to read the book to find out why she wouldn’t want to - but trust me, she has good reason!).

Instead, she decides to disappear, listed among the dead, and take her young son to start a new life in New York, surviving on her wits and building a future for both of them. Her story is a figment of my imagination, but I like to think some of those other brave survivors would understand her choice and approve.

This feature was originally published March 3, 2025.

In 2013, she won a place on the Curtis Brown Creative novel writing course, and started work on her first novel, The Smallest Man. That Bonesetter Woman is her second novel. She lives in Brighton, with her husband and two Tonkinese cats.

The Lost Passenger

Simon & Schuster, 27 February, 2025

RRP: £18.99 | 416 pages | ISBN: 978-1398520684

“A brilliant, big-hearted book with a brave and complex heroine struggling to make a new life for herself and her son after the wreckage of the Titanic. A powerful and inspiring story about finding strength in the face of insurmountable odds” – Anna Mazzola

In the chaos of that terrible night, her secret went down with the Titanic. But secrets have a way of floating to the surface…

Trapped in an unhappy aristocratic marriage, Elinor Coombes sees only lonely days ahead of her. So a present from her father - tickets for the maiden voyage of a huge, luxurious new ship called the Titanic – offers a welcome escape from the cold, controlling atmosphere of her husband’s ancestral home, and some precious time with her little son, Teddy.

When the ship goes down, Elinor realises the disaster has given her a chance to take Teddy and start a new life – but only if they can disappear completely, listed as among the dead. Penniless and using another woman’s name, she has to learn to survive in a world that couldn’t be more different from her own, and keep their secret safe.

An uplifting story about grabbing your chances with both hands, and being brave enough to find out who you really are.

“A juicy story of Dickensian scope, packed with colour and characters that leap from the page. Underpinned with serious themes of class and misogyny, Quinn deftly leads you from domestic turmoil to heart-stopping adventure”

― Jenny Lecoat

“Frances Quinn is one of my favourite historical fiction novelists and this book may just be her best yet! The Lost Passenger is storytelling at its very finest. I cannot recommend this book highly enough!”

― Louise Fein

With thanks to Sarah Harwood.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store