The 1812 Constitution of Cádiz

Helen Crisp and Jules Stewart take us back to a revolutionary moment in European history

As the nineteenth-century began, there was much talk of 'the rights of man'.

Revolutions in the American Colonies and later, more fiercely, in France, had been fuelled by questions about the nature of power and political representation.

A significant episode in this story took place in 1812 in the ancient port city Cádiz, Andalucia. It was here, explains Helen Crisp and Jules Stewart, that Europe's 'first liberal constitution' was written.

Cádiz, a sparkling gem on Spain’s Atlantic coast, claims the title of Europe’s oldest continuously-inhabited city, tracing its origins back 3,500 years to the arrival of the Phoenicians.

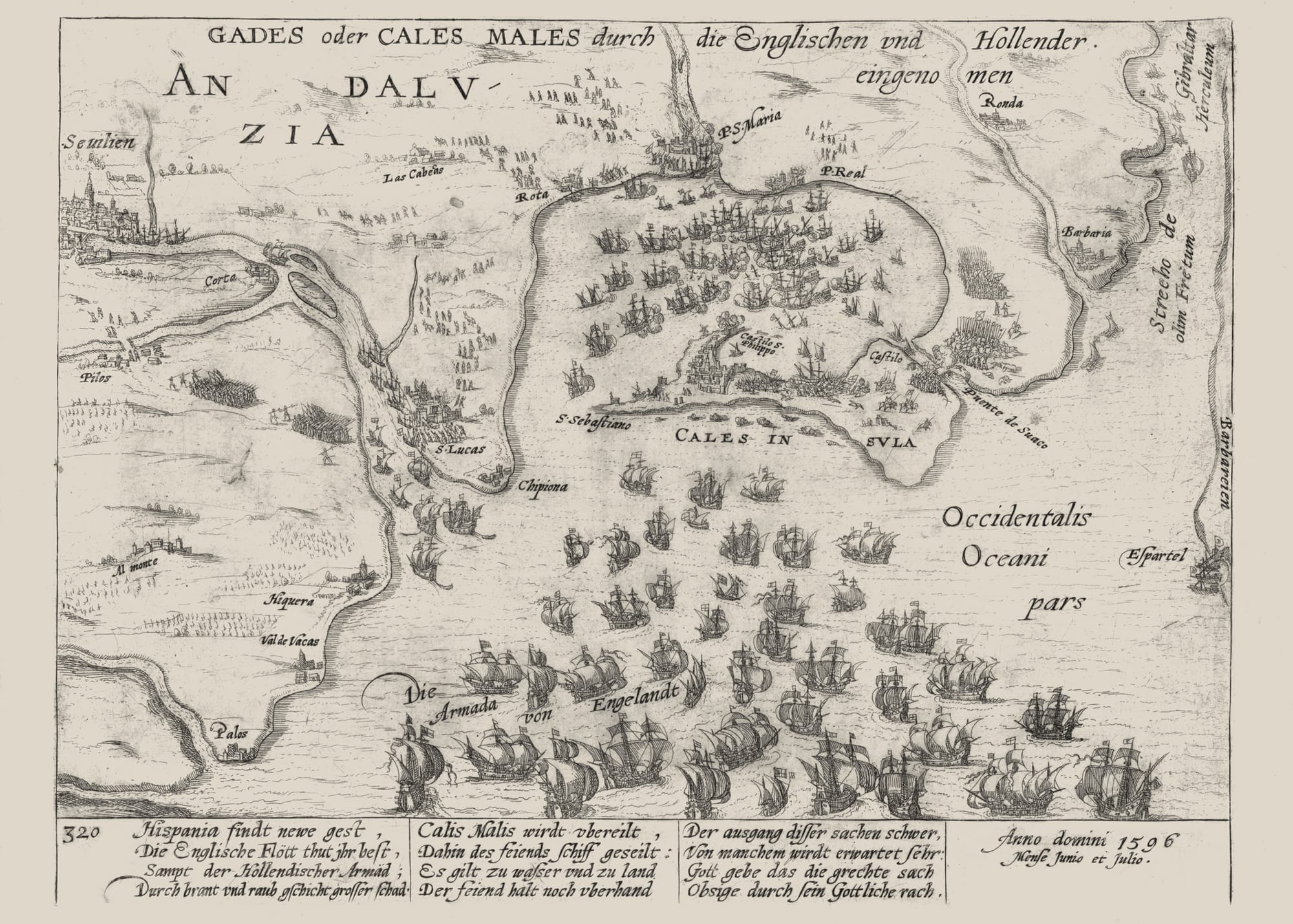

From that time onward, Cádiz has the distinction of being Spain’s most embattled city, having suffered sieges, bombardments and invasions by foreign armies, from Roman times through to the nineteenth-century.

While under siege during the Peninsular War, surrounded by the French on its land sides but kept open to shipping by the British and their allies, Cádiz earned its most illustrious place in history, as the birthplace of Europe’s first liberal constitution.

By March of 1808, two months before the start of the Peninsular War, Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops had crossed the Pyrenees and taken Madrid, deposing King Ferdinand VII who went into exile in France. In May, Napoleon installed his brother Joseph as King of Spain and the emperor set out on a war to bring the rest of the country under French occupation.

While Joseph sat on the throne, the Madrid parliament, known then as it is today as the Cortes, was dissolved, leaving the country without a national administration. One by one, Burgos, Pamplona and other centres of resistance fell to the French troops.

After the surrender of Seville early in 1811, it was decided to move the Cortes to Cádiz, the city that tenaciously held out against Napoleon’s onslaught. Cádiz was in Napoleon’s sights as a key naval base and trading port that was the principal centre of Spanish Empire trade with the American colonies.

While Cádiz was defended by 2,000 Spanish troops, the city welcomed the deputies of the Cortes from across Spain and from the Spanish possessions in Latin America.

As the siege progressed the defending force was reinforced by another 10,000 Spanish partisans as well as British and Portuguese troops. The parliament assembled in the Church of San Felipe Neri, a seventeenth-century Baroque oratory in the centre of the city that was under continual bombardment by the French as the deputies held their debates.

The church underwent a major renovation to adapt it to the role it was to play in the social reformation of Spain. Chief naval engineer Antonio Prat, who designed the city’s defences after the Battle of Trafalgar, was called in to oversee the work.

Semi-circular rows of seats and benches were fitted for the deputies and to the right of the altar canopy, Prat built a seating area for the diplomatic corps. Seats on the other side were installed for stenographers and members of the press, while the upper galleries were reserved for the general public.

The issue of Spain’s simmering colonial crisis, reflected in independence movements that had flared up in several countries, was addressed in the Constitution’s first article, which emphatically stated, ‘The Spanish nation is the joint enterprise of Spaniards of both hemispheres.’

The tenets of a justice system based on equality for all was to be extended to citizens of the colonies as well as peninsular Spain. Enshrined in this article was the doctrine of Habeas Corpus and the banning of arbitrary detention, as well as the prohibition of torture under interrogation.

Cádiz was now the de facto capital of Spain and it was in San Felipe Neri that the deputies drafted the 384 articles that made up the Constitution of 1812. It was promulgated on 19 March, St Joseph’s Feast Day and became popularly known as La Pepa, as Pepe is the Spanish diminutive of José, (Joseph) and as the term constitucióntakes the feminine article la, hence the name La Pepa.

The gathering of progressive politicians, intellectuals, religious leaders and military commanders unfurled the banner of freedom of the press and universal suffrage (for males), along with a radical programme of social and economic reform based on egalitarian principles.

The fundamental principle underlying the Constitution was the concept of national sovereignty. The objective was to limit the despotic powers of the monarchy that had opened the gates to the Napoleonic invasion.

At the same time, most of the deputies aimed to strike down the civil abuses and repression that were the norm of the day. This doctrine was inspired and taken forward by a handful of free-thinkers who supported a liberal, reformist way of life for their country.

Agustín Argüelles was a lawyer and commanding orator who played a key role in drafting the Constitution. He was, like many of his fellow delegates, a sworn enemy of press censorship, the slave trade and the Inquisition. A towering statue of Argüelles stands in the Madrid neighbourhood that bears his name.

In Cádiz, Argüelles fought vigorously for a far-reaching and unambiguous reform of Spain’s antiquated and reactionary social structure. His progressive views were later to earn him a spell in prison in Spain’s Moroccan enclave of Ceuta.

Argüelles was later transferred to Mallorca, where he spent five years behind bars. On his release, Argüelles continued to fight for liberal change and, to avoid another prison term, he fled to England where he was employed as chief librarian to the Whig politician Lord Holland.

Alongside this charismatic crusader for reform stood the radical priest Diego Muñoz-Torrero, a passionate advocate of separation of church and state powers.

Muñoz-Torrero was an extraordinary member of Spain’s orthodox clergy, in that he wholeheartedly espoused the most forward-looking causes under debate in the Cortes. He rose to become the Rector of the University of Salamanca, the most august academic title in Spain.

He proclaimed his fervent views as a supporter of freedom of the press in an address to the assembly. ‘We would be betraying the aspirations of our people and providing arms to the governing forces we have begun to overcome if we failed to declare freedom of the press. Censorship is the last bastion of the tyrannical rule that has instilled fear in us for centuries.’

As such, Cádiz became the springboard for Spain’s first system of separation of powers in the country’s history. Of the 384 articles of the Constitution, 250 dealt with this issue.

The state was organised into separate and independent legislative, executive and judiciary branches. The Cortes, with its single chamber of deputies, stood as the nation’s legislature. Each Spanish colony was invited to send one representative to the Cortes. Egalitarian principles prevailed throughout the constitutional process, to the point that Decree XXXI stated categorically that 'criollos', 'mestizos' and 'native Indians' were given the same status as Spanish citizens if they wished to join government bodies, the Church or serve in the military.

Cádiz is enormously proud of this moment in its history, the façade of San Felipe Neri is adorned with plaques celebrating its role in housing the deputies who drafted the ground-breaking Constitution and the building next door is the Museum of the Cortes of Cádiz.

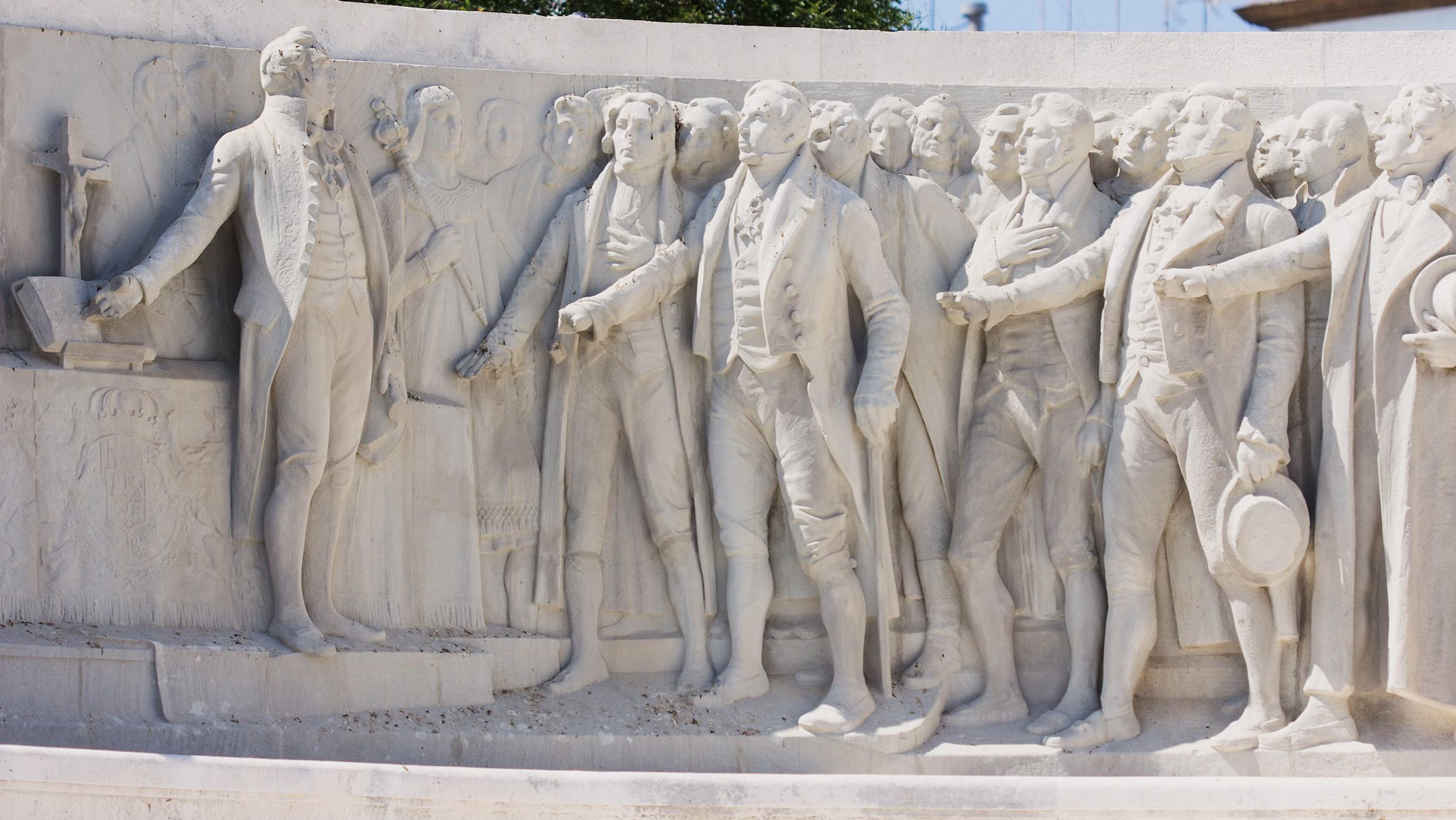

As the centenary of the Constitution came into view a competition was held to design a monument for 1812, to commemorate the Cádiz parliament, the Constitution and the siege.

This huge edifice now stands in the Plaza de España, designed by the architect Modesto López Otero and the sculptor Aniceto Mariñas. The monument is adorned with emblematic figures representing the Constitution, War, Peace and Agriculture, with figures of the deputies swearing their loyalty to the Constitution, while an empty chair emphasises the absence of the monarch.

The Constitution of 1812 represented a historical landmark in the advance of European political enlightenment.

The Duke of Wellington, on a visit to Cádiz to meet with the Cortes, expressed high praise for this charter. In a letter to the Chancellor Lord Bathurst, he wrote: ‘I wish that some of our reformers would go to Cádiz and see the benefits of a sovereign popular assembly and of a written constitution.’

The Constitution sought to limit the power of the monarchy, however, it was summarily revoked by Ferdinand VII when he returned to the throne after the defeat of the French •

This feature was originally published October 24, 2024.

Cádiz: The Story of Europe's Oldest City

Hurst, 28 November, 2024

RRP: £25 | 324 pages | ISBN: 978-1911723615

This is the tale of Western Europe’s oldest continuously inhabited city, a 3,000-year history of war and seafaring, culture and commerce, liberalism and resistance.

Helen Crisp and Jules Stewart offer a vibrant account of Cádiz past and present, from its ancient founding myths to its reinvention as a trendy tourist destination. They illuminate Cádiz’s experiences under Roman and Moorish rule; explore its centuries of maritime warfare, from Francis Drake to the Battle of Trafalgar; and probe its role in Spain’s ‘Golden Age’ of empire, when it dominated trade with the New World.

As Spain’s de facto capital during the Peninsular War, Cádiz also produced Europe’s first liberal constitution in 1812. And in 1936, it was the port of entry for Franco’s troops, mustered to overthrow the Republic.

Cádiz has excited the passions of travellers for centuries. Lord Byron was enchanted by the ladies of the city, whom he described as ‘form’d for all the witching arts of love’. Benjamin Disraeli fell in love with Cádiz in 1830, seeing ‘Figaro in every street and Rosita in every balcony’. This beautifully illustrated book, the first to tell the full story of this intriguing and extraordinary city, brings its past to life.

“Cádiz is one of Spain’s most beautiful and seductive cities, as rich in history as it is in gastronomy and flamenco music. It is also one of the less overwhelmed by tourism. Whether it will remain so after this elegantly written and enticingly knowledgeable history is a matter for some trepidation”

― Sir Paul Preston, author of Perfidious Albion: Britain and the Spanish Civil War

“Helen Crisp and Jules Stewart capture the essence of this unique and ancient settlement, with just the right mix of facts, myths and insight. A joy to read, it moves through 3,000 years of history with elegance and pace. An engaging and thoroughly enjoyable book”

― Jason Webster, author of Duende and The Book of Duende

With thanks to Jess Winstanley.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store