The Battle of Fredericksburg (Part 1) – Crossing the Rappahannock

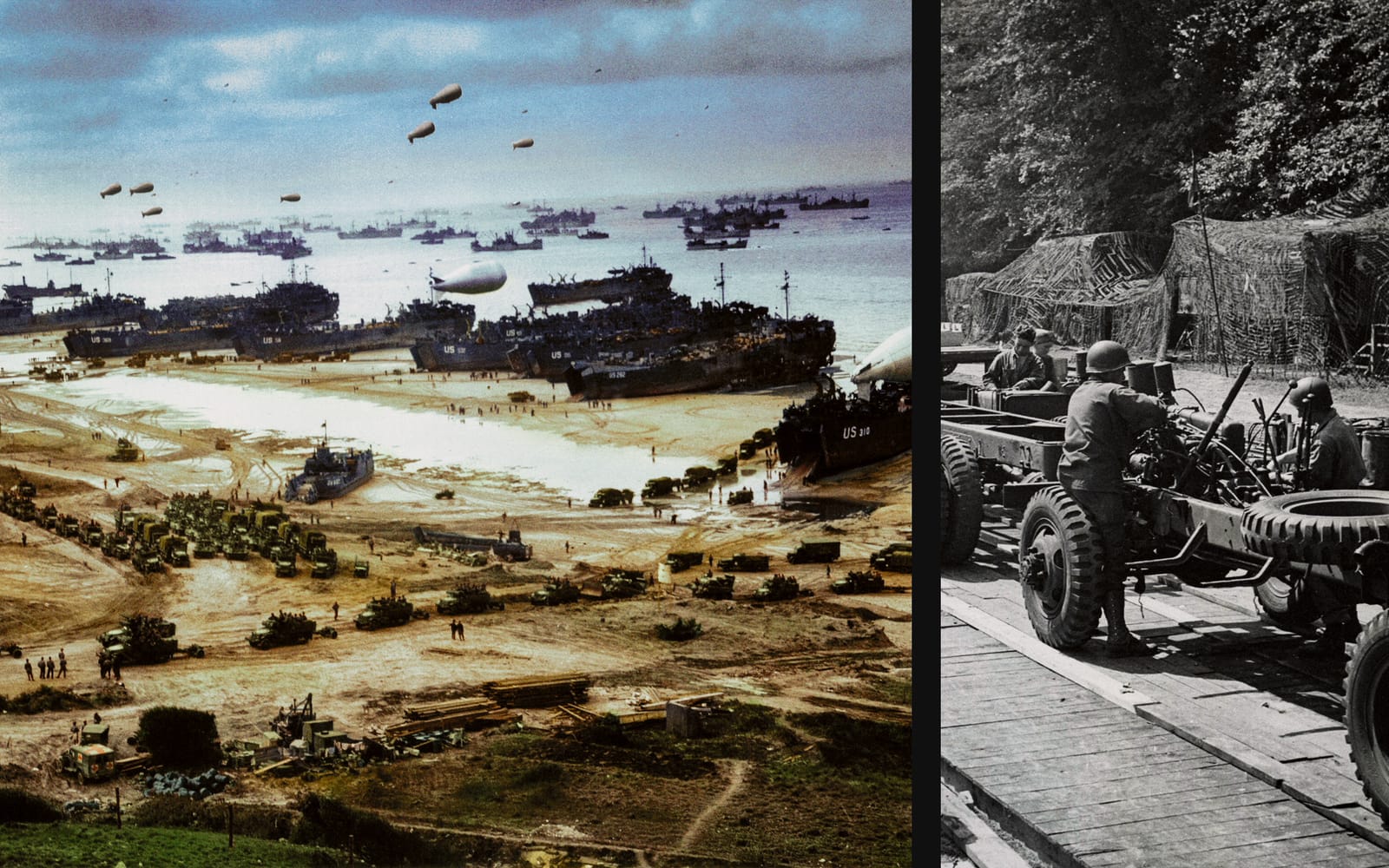

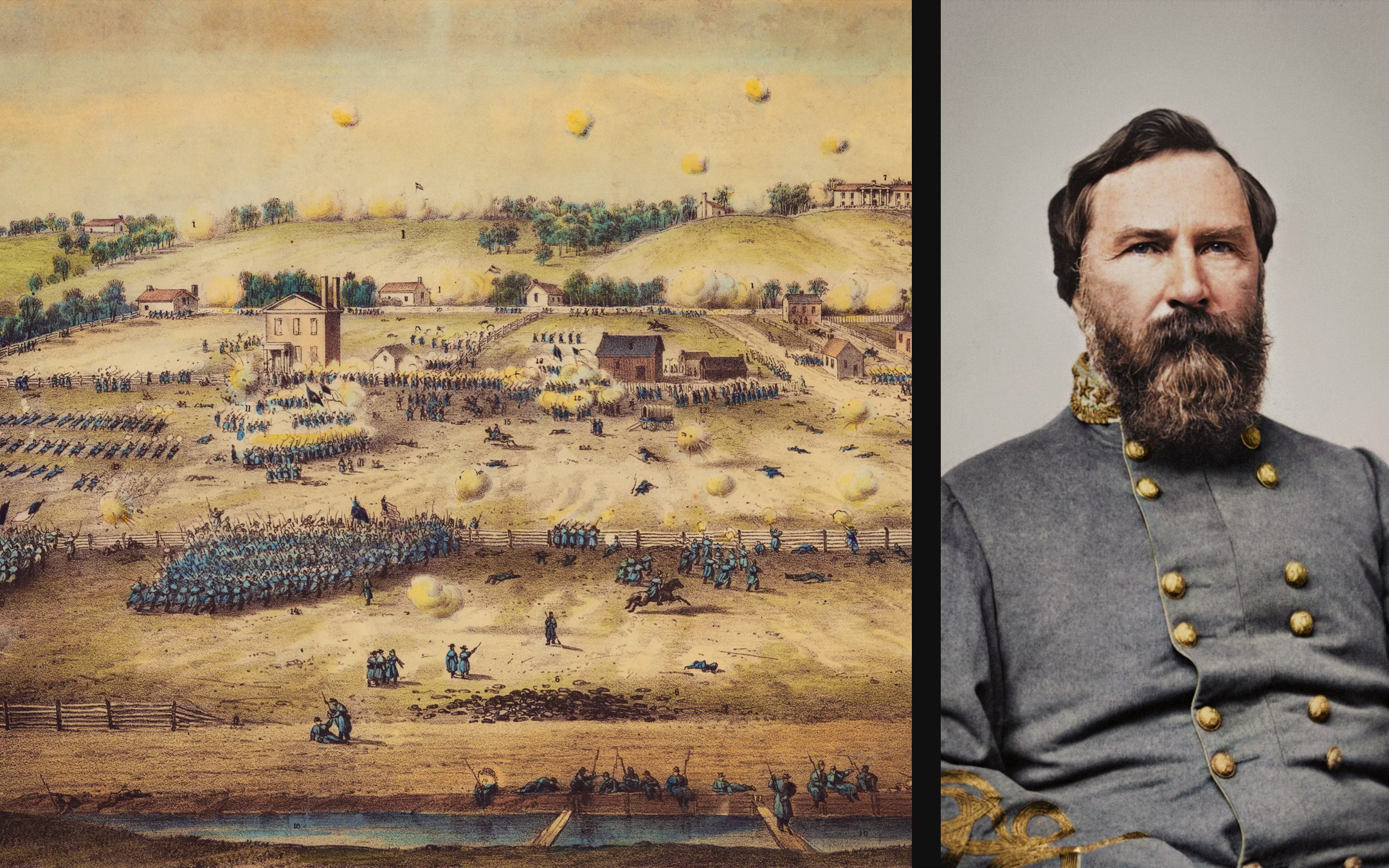

Illustrated eyewitness accounts of the Union's amphibious assault of Fredericksburg on Thursday, December 11th, 1862

Union Major General Burnside's failed invasion of the city of Fredericksburg, between the 11th and 15th of December, 1862, heralded a turning point in the American Civil War. Unseen Histories presents illustrated eyewitness accounts alongside remastered contemporaneous pictures taken in the era.

After the pyrrhic victory at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Union morale slowly began to build. President Abraham Lincoln, having issued the Emancipation Proclamation just mere days following the Battle of Antietam, needed the Union Army to further take the fight to the rebels in Virginia.

Words by Jeremy Martin

Photographs Remastered and Colourised by Jordan Acosta

Jeremy Martin: Following the issue of the Emancipation Proclamation1, Lincoln replaced Major General George B. McClellan2 with Ambrose E. Burnside. Burnside, a West Point graduate of 1847 – who hesitantly accepted the position on November 9, 1862, in Warrenton, Virginia, after finding out his long-time rival Joseph Hooker would be offered the position if he did not accept.

Following McClellan’s bitter exit, Major General Burnside reluctantly took control of the Army of the Potomac, pressured by Lincoln to take quick and aggressive action to capture Richmond.

The Race to Richmond

Burnside decided to press on to Richmond through the mid-way Virginia town of Fredericksburg. Fredericksburg held a great deal of cultural significance to the Confederates, who often attempted to connect the Revolutionary War to their rebellion. Fredericksburg was George Washington’s childhood hometown, as well as the residence of Revolutionary War heroes such as John Paul Jones and James Monroe. However, on that fateful December week, Fredericksburg’s significance would forever be changed from its Revolutionary past, to a much more violent, bloody, and divisive history.

The following excerpts are from the diaries and recollections of people that experienced Fredericksburg from entirely different perspectives up to – and including – Saturday December 11, 1862, supplemented by drawings and photographs taken on the day or in the same period.

The first perspective is recounted by a Union soldier, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Fredericksburg. Also noted are the recollections of both a Confederate States Army captain and soldier, experiencing the horrors of the front line against a tireless force. The final stories are related by an unnamed civilian, who experienced that battle unfold quite literally on her front porch.

John

Union Army soldier John G. B. Adams was a Second Lieutenant serving in Company I of the 19th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry during the Battle of Fredericksburg.

We continued the march through the valley to Warrenton, where General McClellan was relieved of the command of the army and General Burnside succeeded him. Nearly all the men were sad at the loss of McClellan. He was our first love, and the men were loyal and devoted to him. I did not share in this sorrow. My faith had become shaken when we retreated from before Richmond, and when he allowed Lee's army to get away from Antietam I was disgusted, and glad to see a change. Sad as the army felt at the loss of McClellan, they were loyal to the cause for which they had enlisted, and followed their new commander as faithfully as they had the old.

We arrived at Falmouth about the middle of November, and went into camp two miles from the town; here we spent our second Thanksgiving. No dance for the officers this year. We had a dinner of hard tack[3] and salt pork, and should have passed a miserable day had not the commissary arrived with a supply of “Polandwater,” and the officers were given a canteen each. The men had the pleasure of hearing our sweet voices in songs of praise from the “home of the fallen,” as our tent was called.

William

Confederate States Army soldier William B. Howard enlisted in the Seventh Regiment N.C, leaving Kinston, North Carolina in early May, participating in eight battles across Northern Virginia during the summer of 1862.

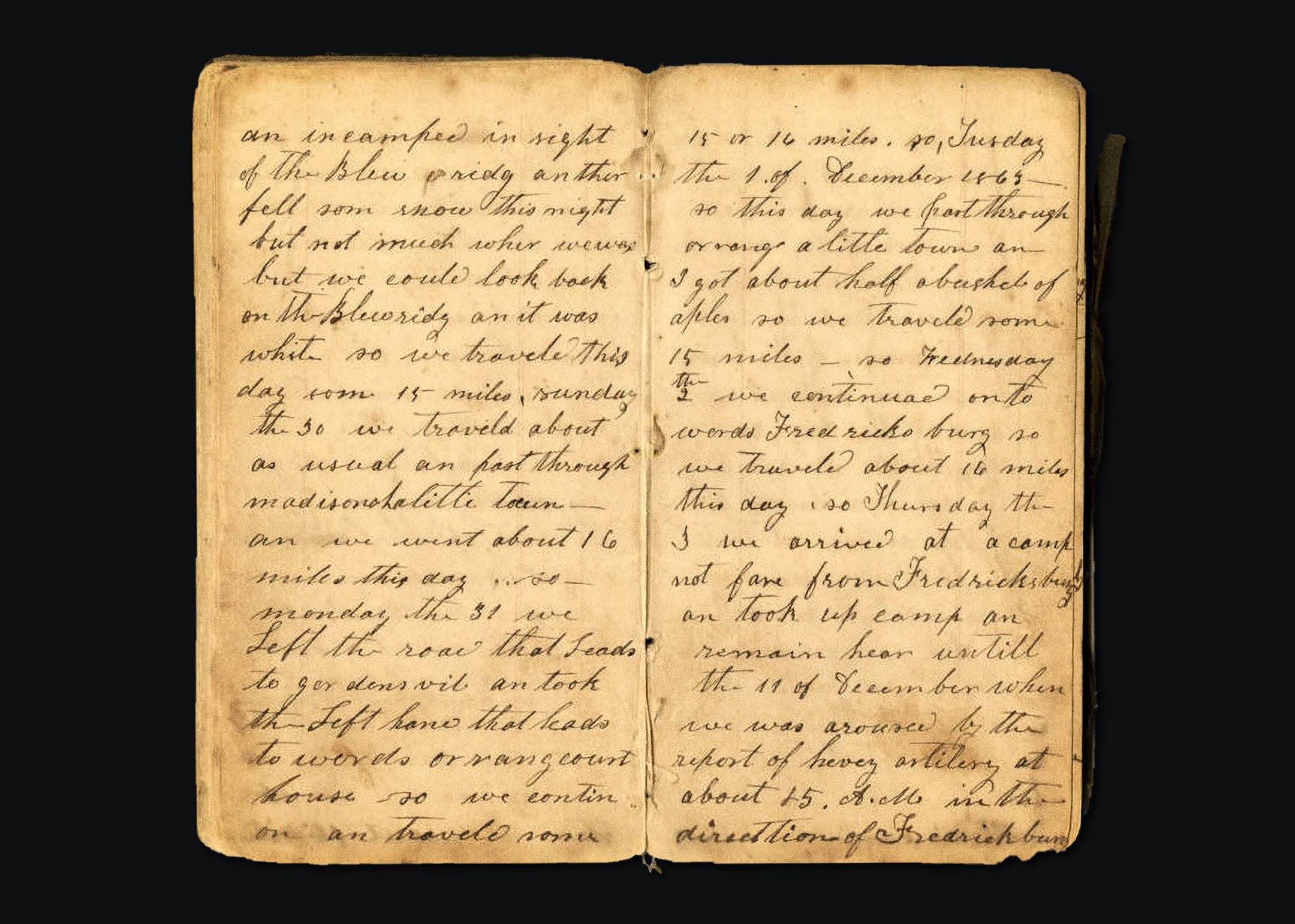

NB: Commas and full stops have been for clarity, whilst preserving Howard's written vernacular.

[W]e rose very erly an marched off an streech the foot of the bleuridge an commenced winding around an back an round anround untill I got nearly at the top, when I stopt an looked back and could see our Long lines of infinity winding around side the mountain, an our Long Train of artilery in front an Long train of wagons an ambulances in the rare it was abutyful sight to Look back on, an more espeseley to look on the butiful valey behine an several butyful towns too.

[T]his was a grand sight to one that never saw such her the hills stood above us most as high as the eye could see, an great rocks hangin out lik they had as soon fall as to stay when they was, so we traveld on very hard all day an came to the foot of the bleuridge about sundown, an camped on the side of the hills an it was about as Cole a wether as ever I felt.

[W]e travel about 18 miles this day Saturday the 29 [November] an incamped in sight of bleu ridge, an ther fell som snow this night but not much wher we was but could look back on the Bleuridg an it was white so we travled this day some 15 miles. Sunday the 30 we traveld about as usual an past through madisonchalitte town, an we went about 16 miles this day, so monday the 31 we left the road that leads to gordonsvil, an took the left lane that leads to words organg court house so we contin on an traveld some 15 or 16 miles.

Amphibious Assault

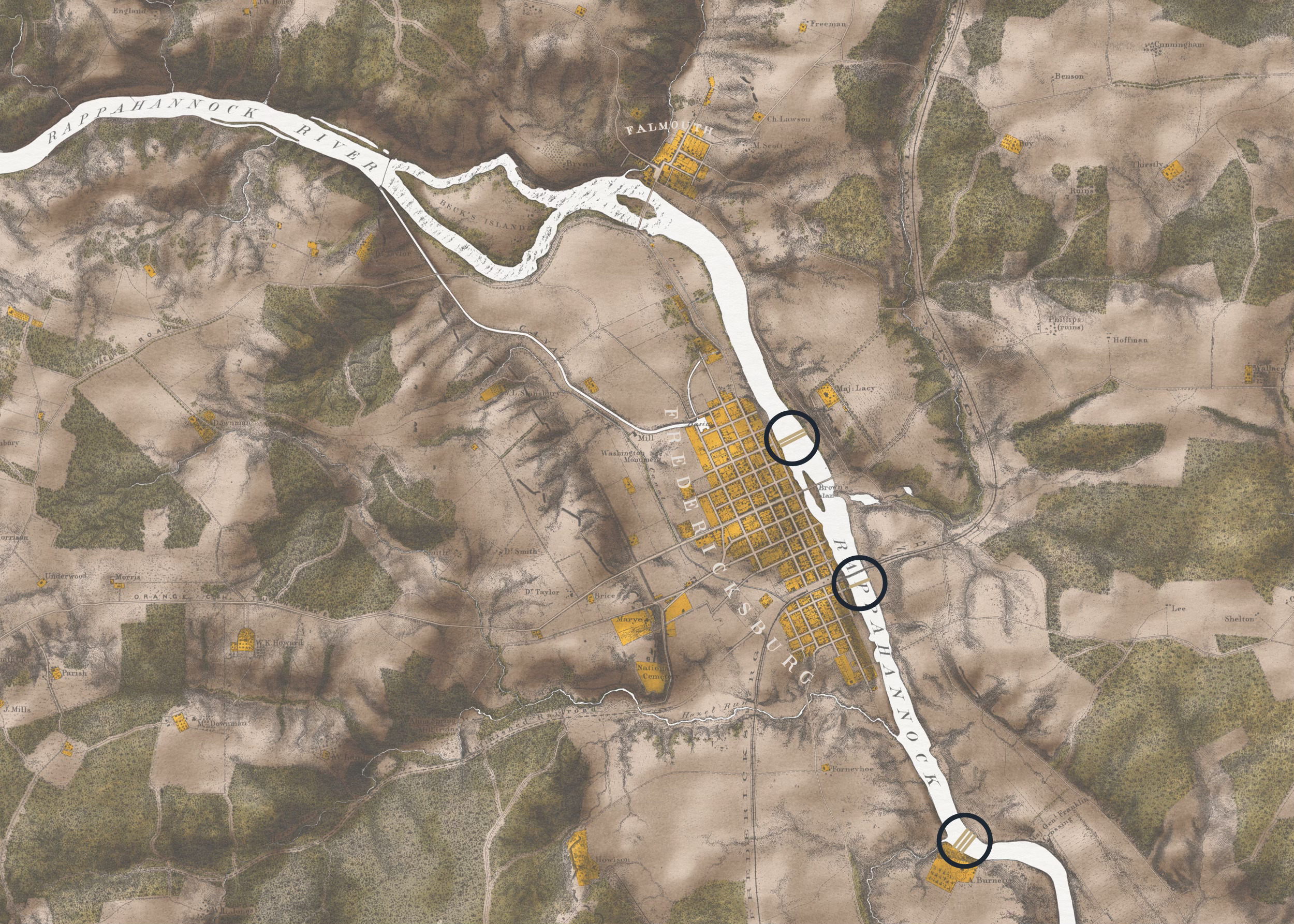

Burnside originally wanted to cross the Rappahannock River at Skinker’s Neck, just south of Fredericksburg. Burnside caught the attention of Confederate forces led by D.H. Hill and Jubal Early, and instead decided to cross the Rappahannock River at the town itself. However, supply lines and logistical networks were slow-moving. When arriving at Fredericksburg on November 17, supplies to cross the bridge did not begin to arrive until eight days later on November 25, eliminating any element of surprise that Burnside may have had eight days prior.

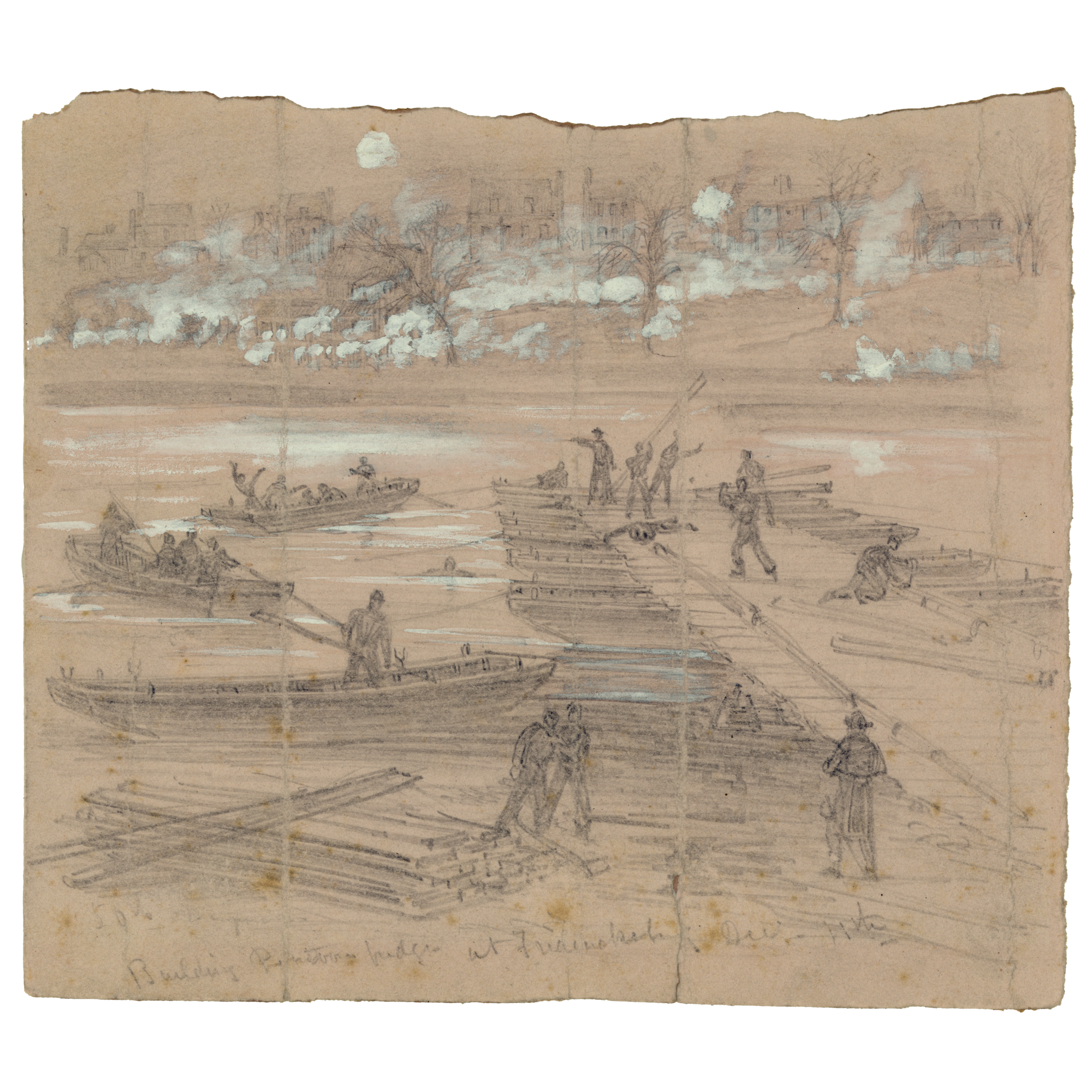

On December 11, at 15:00, Union soldiers began to cross the Rappahannock River. As the United States’ first amphibious assault in its history, the crossing was a brutal and tumultuous task. Not only were soldiers faced with freezing temperatures, but Confederate sharpshooters, led under former Congressman and Mississippian William Barksdale, also shot at the incoming Union soldiers.

John

We remained undisturbed until the morning of December 11, when we were ordered to the banks of the Rappahannock River, opposite Fredericksburg. Here we found a pontoon bridge partially laid, and the engineers doing their best to complete it. Our batteries were posted on the hills in rear of our line, and were vigorously shelling the city, but the rebel sharpshooters were posted in cellars and rifle pits on the other side, and would pick off the engineers as fast as they showed themselves at work.

At last volunteers were called for by Colonel Hall, commanding the brigade, and the 19th Massachusetts and 7th Michigan volunteered. We took the pontoon boats from the wagons, carried them to the river, and as soon as they touched the water filled them with men. Two or three boats started at the same time, and the sharpshooters opened a terrible fire. Men fell in the water and in the boats. Lieutenant-Colonel Baxter of the 7th Michigan was shot when half-way across. Henry E. Palmer of Company C was shot in the foot as he was stepping into the boat, yet we pressed on, and at last landed on the other side.

As soon as the boats touched the shore we formed by companies, and, without waiting for regimental formation, charged up the street. On reaching the main street we found that the fire came from houses in front and rear. Company B lost ten men out of thirty in less than five minutes. Other companies suffered nearly the same. We were forced to fall back to the river, deploy as skirmishers, and reached the main street through the yards and houses.

As we fell back we left one of our men wounded in the street; his name was Redding, of Company D, and when we again reached the street we found him dead,– the rebels having bayoneted him in seven places.

The regiment was commanded by Capt. H. G. O. Weymouth, Colonel Devereaux being very sick in camp. Captain Weymouth went from right to left of the line, giving instructions and urging the men forward. My squad was composed of men from companies I and A.

We had reached a gate, and were doing our best to cross the street. I had lost three men when Captain Weymouth came up. “Can't you go forward, Lieutenant Adams?” he said. My reply was, “It is mighty hot, captain.” He said, “I guess you can,” and started to go through the gate, when as much as a barrel of bullets came at him. He turned and said, “It is quite warm, lieutenant; go up through the house.” We then entered the back door and passed upstairs to the front. Gilman Nichols of Company A was in advance. He found the door locked and burst it open with the butt of his musket. The moment it opened he fell dead, shot from a house on the other side of the street. Several others were wounded, but we held the house until dark, firing at a head whenever we saw one on the other side.

Val

Confederate States Army Captain Valerius Cincinnatus Giles enlisted in the 4th Texas Infantry Regiment, Company B, known as the "Tom Green Rifles" from Travis County, TX, commanded by John Bell Hood under Robertson's Division at Marye's Heights under James Longstreet.

The old town of Fredericksburg nestled in the lower valley along the south bank of the River. The range of hills on the north side, known as Stafford Heights, bristled with artillery which gleamed and glittered in the bright December sun.

My brigade was stationed on the foot-hills about a mile and a half from the river, opposite the town. Fifty houses were on fire in half an hour after the terrible bombardment began.

Old men, women and children came pouring out of that stricken town, seeking safety back of our lines. Women were carrying babies and leading little children, many of them crying and all frightened. The pale, eager faces of those fleeing refugees appealed to the heart of every soldier there, but we could do nothing for them except make way for them to pass to the rear. With all this stream of homeless, heart-broken people passing us, there was something now and then that made the soldier laugh, although his heart was overflowing with pity at the sad sight before him. I saw one boy leading a dog, a common cur at that, and carrying a monkey on his shoulder. The dog sat back on the rope and the monkey kept pulling the boy's cap off and throwing it on the ground. The little fellow was mad all over. A little tot of a girl was hugging up a rag doll as big as she was. Some were carrying cats, and I noticed one little girl with a parrot.

Now the enemy began to come, and it looked like the whole world was coming. They filed up the river, down the river, and all over the town and lower valley. The sunlight gleamed and sparkled on muskets, cannon and the trappings on the artillery horses as the long line of blue kept pressing on. An interested comrade standing near me jokingly called out: ‘Say, Captain, where shall we get dirt enough to bury all those men?’

Unknown Woman

On Thursday, December 11th, we were awakened by two cannon. At 15 o'clock we arose and dressed. About six the firing began in earnest. We packed our trunks amid it all, made a fire in the cellar, and thither repaired. We had not been there an hour when a shell went through our attic room, breaking bedsteads, etc. One shot went through the parlor; five in all through the house. As they passed, the crash they made seemed to threaten instant death to all; it sounded as though the house were tumbling in, and would bury us in its ruins. We knew the danger, but our trust was in God, and we were calm. Aunt Clara (the colored woman who lives opposite) was with us.

Darkness came on, and the cannonading ceased, B. went to the gate and returned with the news that there was fire in different parts of the town, and that a company of our men were at the corner bring on the pontoon bridge. Though the bombardment had ceased, the musketry sounded to my ears yet more awful, for I knew they were fighting in the streets. My ears are suddenly shocked by a shout of demoniacal glee – "Here are the rebels! here are the d — d rebels! fire, boys! fire! " Two dreadful cries rend the air — our gallant Capt. Cook is killed at our corner. To hear the fiendish cry of the enemy unnerved me more than the explosion of the thousands of that burst around us.

Whomever this may have been, this woman witnessed one of the most brutal battles of the Civil War. While there were some civilians in the town of Fredericksburg during the battle, many citizens of Fredericksburg fled the town in search of safety from the incoming Union forces. Many enslaved peoples escaped from their plantations and joined the Union lines across the Rappahannock River seeking emancipation. In lieu of the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved peoples in the Confederacy were now freed under the jurisdiction of the United States. Thus began the process of emancipating enslaved peoples throughout the Confederacy. Fredericksburg was one of the first large-scale engagements where enslaved peoples were able to self-emancipate and escape into Union lines.

The First Night

The Union soldiers crossed the Rappahannock River, and pushed Barksdale’s Mississippi sharpshooters out of the town. By nightfall, starving Union soldiers ransacked rebels' homes and businesses to find food, supplies, and other spoils of war.

John

As night came on we advanced across the street and the rebels retired. We posted our pickets and went into the houses for rest and observation. The house my company now owned was formerly occupied by a namesake of mine, a music teacher. I left the men down stairs while I retired. The room I selected was the chamber belonging to a young lady. Her garments were in the press, and the little finery she possessed was scattered about the room. Fearing she might return I did not undress, but went to bed with my boots on. I was soon lost in peaceful slumber, when a sergeant came and said I was wanted below. Going to the kitchen I found the boys had a banquet spread for me. There was roast duck, biscuit, all kinds of preserves, spread upon a table set with the best china. We were company, and the best was none too good for us. After supper we went up stairs, and the men were assigned, or assigned themselves, to rooms.

Unknown Woman

All being now quiet for a time, we lie down, but not to sleep; for, bark! they are breaking into houses like so many demons. With terrible force they throw themselves against our doors, back and front, but an officer (Yankee, though he was.) saved us. We hear them break into your house, but dare not utter a word, lest they slay us. Oh! who can tell the horrors of that night? They order my father out, declare that he has wine in his cellar, & c. He assures them he has only his unoffending wife and eight children there.

Thus passes the night, the fire still raging. About 8 o'clock the flames burst forth in our vicinity, and we expect every moment to find our own roof on fire. In the midst of the excitement a soldier rushed in with his bayonet, which he pointed at my father's breast and ordered him to follow him. My father asked why? but the manner in which he repeated the order convinced him that he must follow or die. This occurred in the back porch; I was at that time in the front porch watching the sparks and expecting our house every moment to take fire. They carried father to headquarters, and, after accusing him of firing on them from his house, he was related the officer before whom he was arraigned fending a lie in the face of the accuser, and innocence in that of the accused. While he was gone, soldiers came to me at the front door, and to mother behind, and assured us that the house was on fire; but such was not the case. The trick did not succeed, nor did the story afford them the opportunity they sought to rob the house.

The Calm Before the Storm

On the morning of December 12, what was left of Burnside’s army crossed the Rappahannock River. It appeared almost as if the water from the banks of the Rappahannock River was overpouring into Fredericksburg. Union soldiers continued to loot and pillage the town as they crossed the pontoon bridges that were constructed. December 12 was a day of silence and preparation for the day to come.

Without knowing it, the two armies were preparing for some of the heaviest fighting that they had seen since Antietam. As darkness filled the skies over Fredericksburg, both armies were on edge, anticipating the horrors that awaited them on Saturday, the 13th of December, 1862 •

This Viewfinder feature was originally published December 11, 2021.

Further Reading

Jeremy Martin: The following books offer further information on the history of the Battle of Fredericksburg. Some books are on general Civil War history, but offer sections on the Battle of Fredericksburg. These books help further dissect and digest the battle further.

⇲ The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian by Shelby Foote (Vintage Books, November 1986)

⇲ Simply Murder: The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862 by Chris Mackowski & Kristopher D. White (Savas Beatie, 2013)

⇲ A Worse Place Than Hell: How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation by John Matteson (W. W. Norton & Company, February 2021)

⇲ Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! (Civil War America) by George C. Rable (The University of North Carolina Press, November 2009)

Rags and hope; the recollections of Val C. Giles, four years with Hood's Brigade, Fourth Texas Infantry, 1861-1865 by Valerius Cincinnatus Giles (New York, Coward-McCann, 1961)

⇲ Reminiscences of the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment by John G. B. Adams (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1899)

Richmond Times. ⇲ Horrors of a bombardment, The Daily Dispatch: January 2, 1863

More

The Battle of Fredericksburg – Storming Marye's Heights

After the amphibious assault by the Union army two days prior, both armies, unknowing of the carnage to come, prepared for battle

The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by US President Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, changing the legal status of millions of African Americans from enslaved to free. It read, "That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom."; ↩

McClellan explained, “In parting from you I cannot express the love and gratitude I bear to you. As an army you have grown up under my care. In you I have never found doubt or coldness. The battles you have fought under my command will proudly live in our nation’s history. The glory you have achieved, our mutual perils and fatigues, the graves of our comrades fallen in battle and by disease, the broken forms of those whom wounds and sickness have disabled–the strongest associations which can exist among men–unite us still by an indissoluble tie. We shall ever be comrades in supporting the Constitution of our country and the nationality of its people.” All throughout the captured southern town, Union soldiers wept and begged for him to stay. After all, McClellan was known as The Young Napoleon, and was careful about sending soldiers into the fray of combat to prevent unnecessary deaths; ↩

Hard tack, or hardtack, is a biscuit (or cracker) made by combining, flour and water (and occasionally salt), commonly used as a staple ration for the military prior to the 20th century. During the American Civil War, it was often softened in a soldier's morning coffee, or moistened to turn into mush which was then flavoured and cooked; ↩

A bushel is a measurement used traditionally in agriculture, the equivalent to 2150 cubic inches, 8 US dry gallons, or 36 litres; ↩

Molasses is a thick, dark liquid made from refining sugarcane or sugar beets into sugar, commonly used to sweeten food ↩

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store