The Battle of Fredericksburg (Part 2) – Storming Marye's Heights

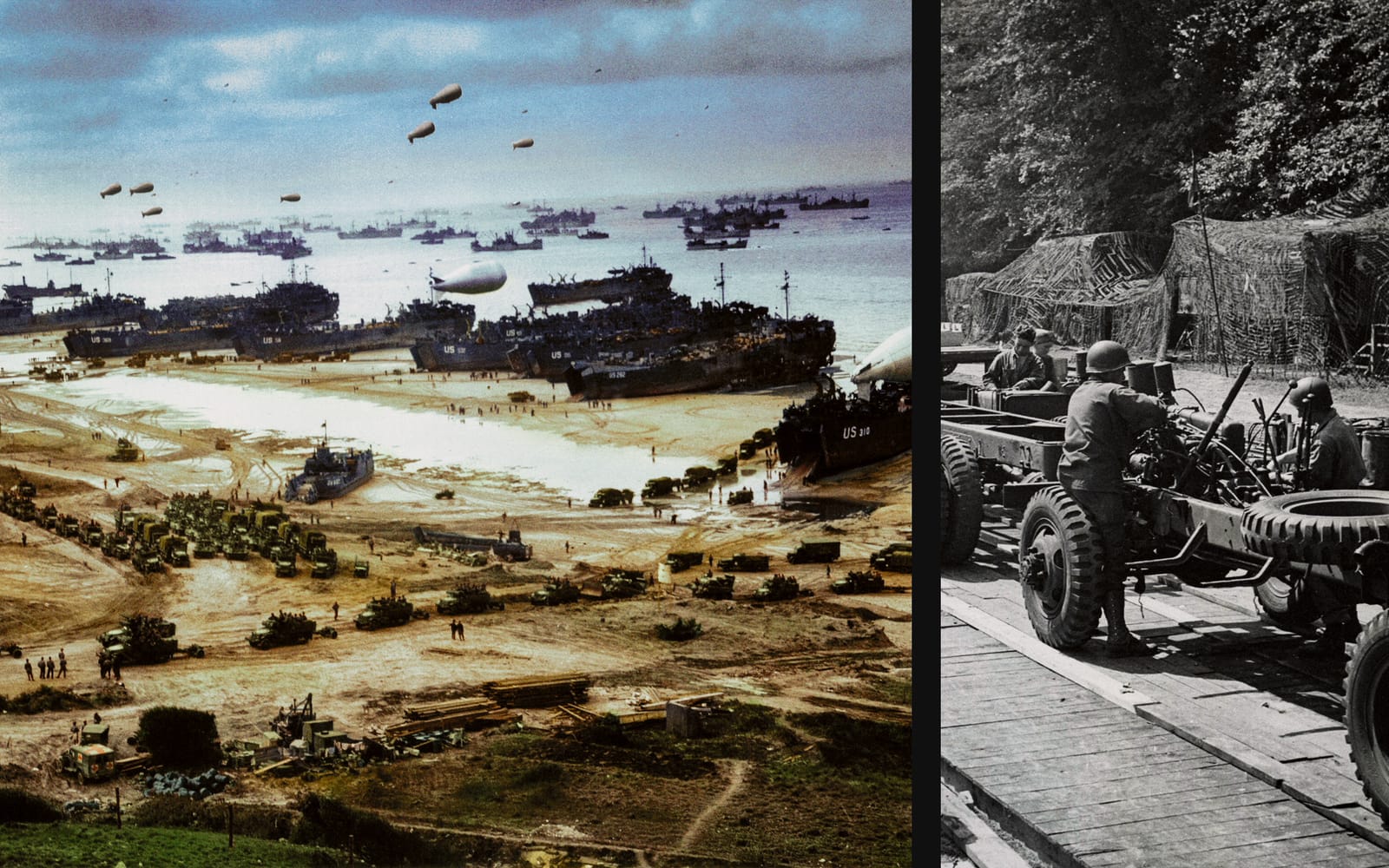

After the amphibious assault by the Union army two days prior, both armies, unknowing of the carnage to come, prepared for battle

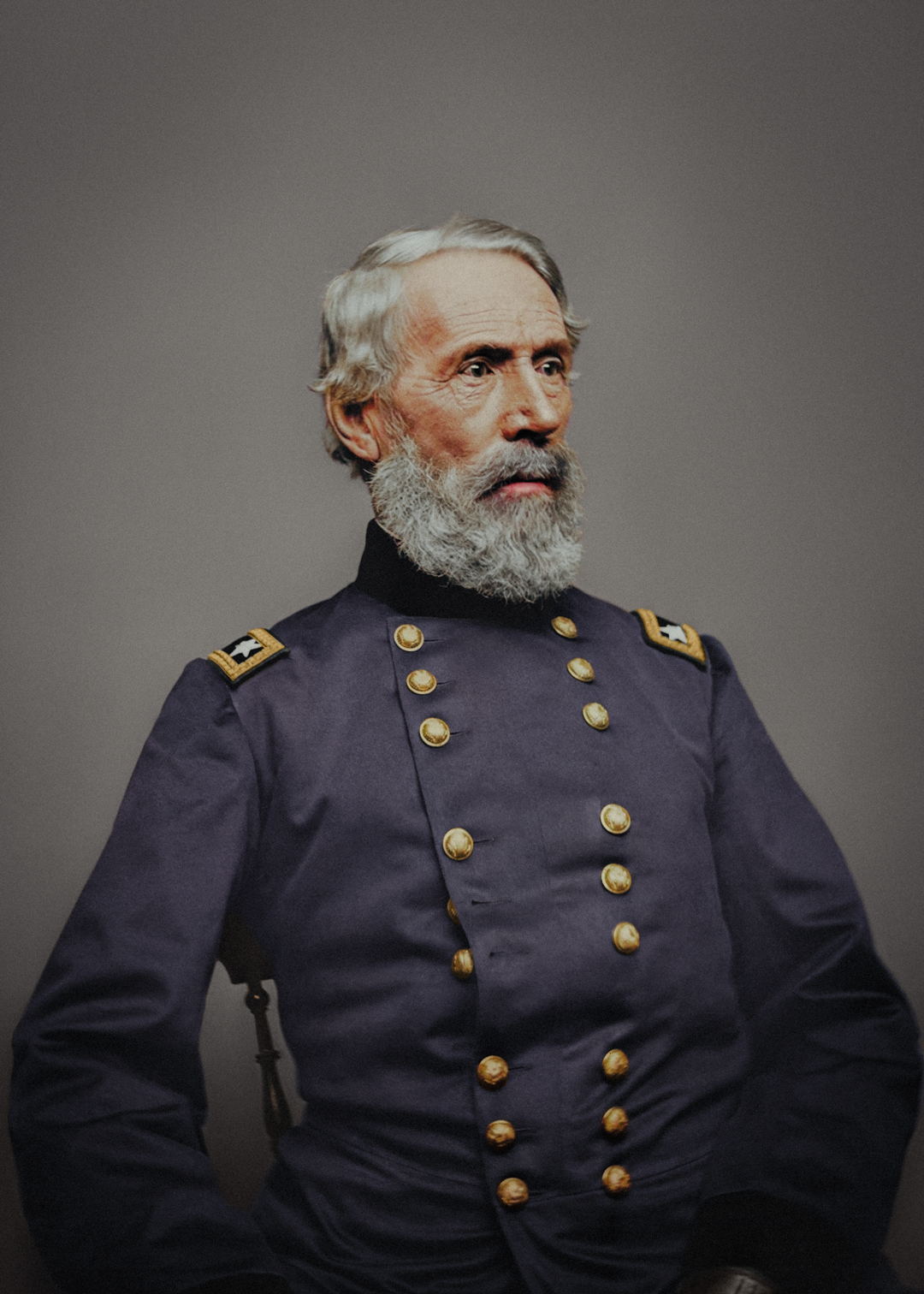

Union Major General Burnside's failed invasion of the city of Fredericksburg, between the 11th and 15th of December, 1862, heralded a turning point in the American Civil War. Unseen Histories presents illustrated eyewitness accounts alongside remastered contemporaneous pictures taken in the era.

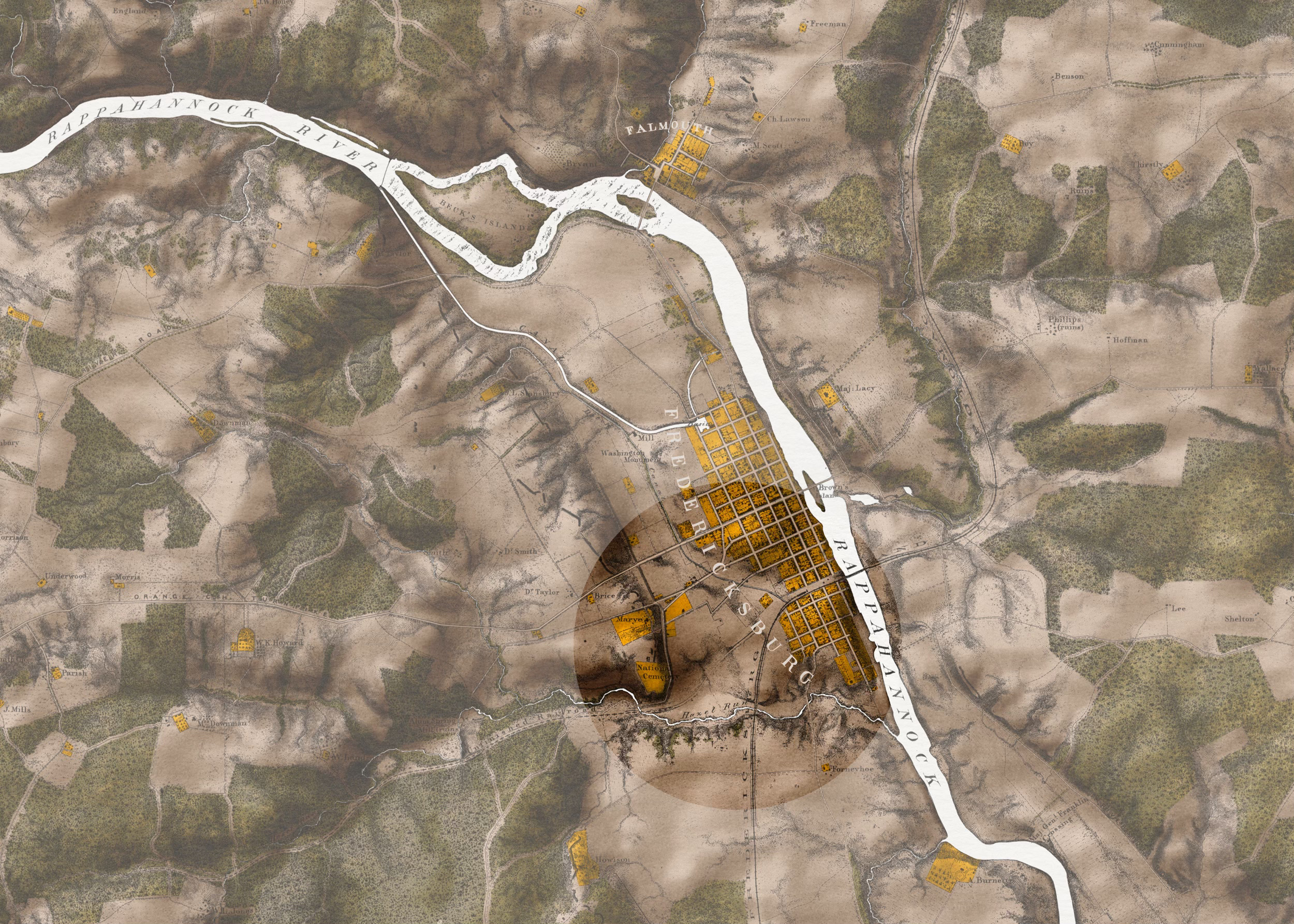

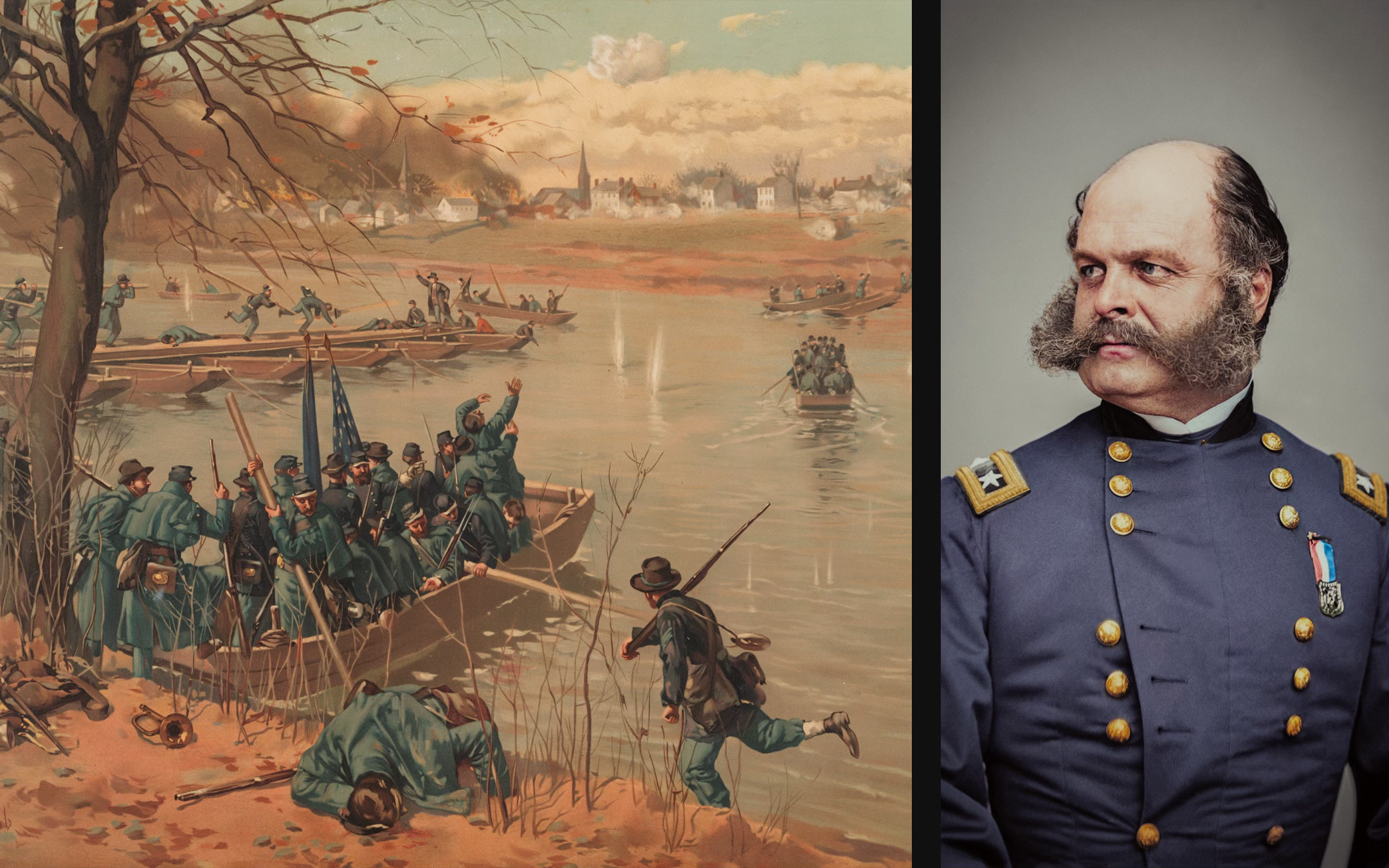

On the morning of December 13, 1862, the town of Fredericksburg, Virginia was shrouded in thick fog from the Rappahannock River. After the amphibious assault by Major General Burnside's Union army two days prior, both armies, unknowing of the carnage to come, prepared for battle.

Words by Jeremy Martin

Photographs Remastered and Colourised by Jordan Acosta

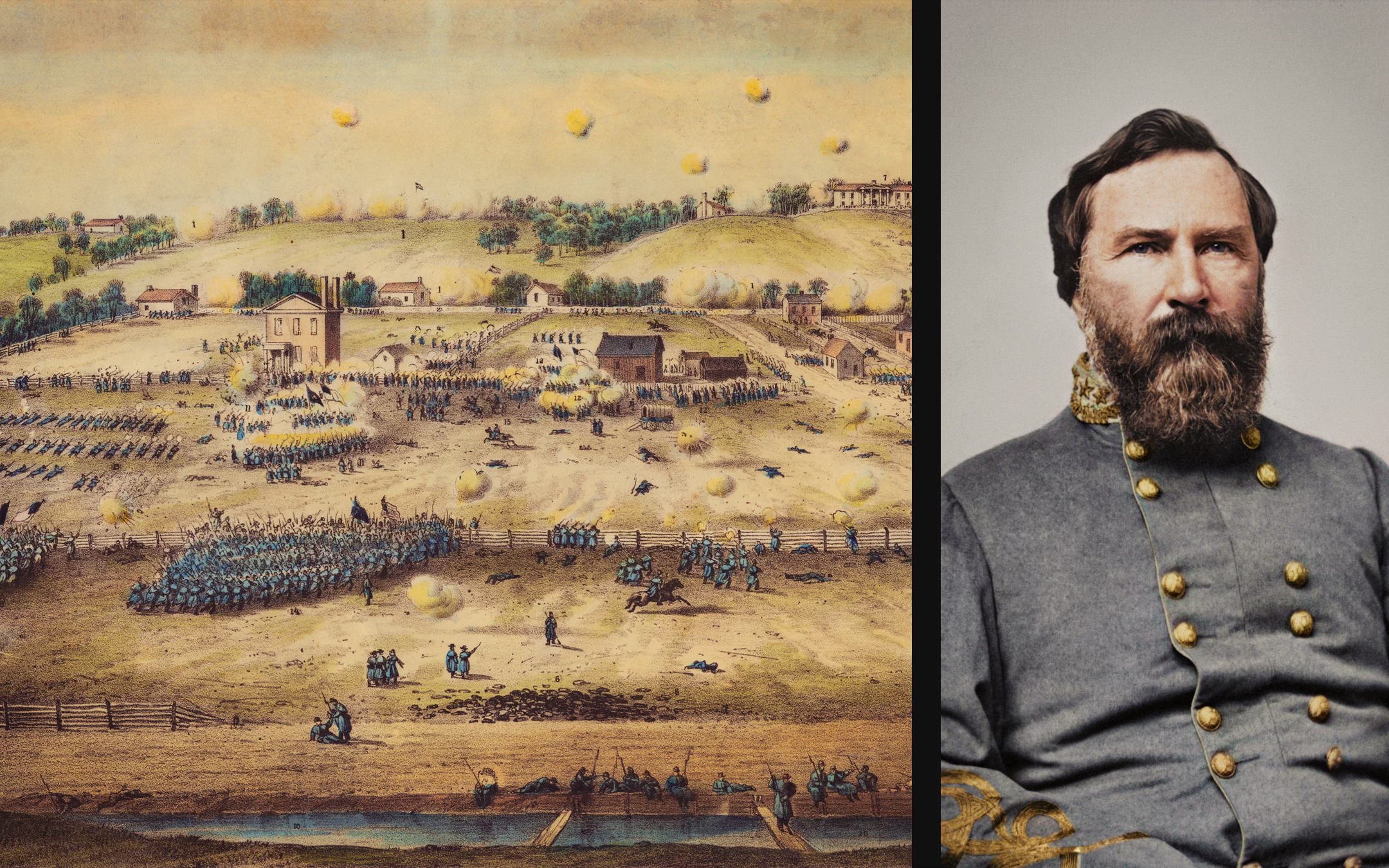

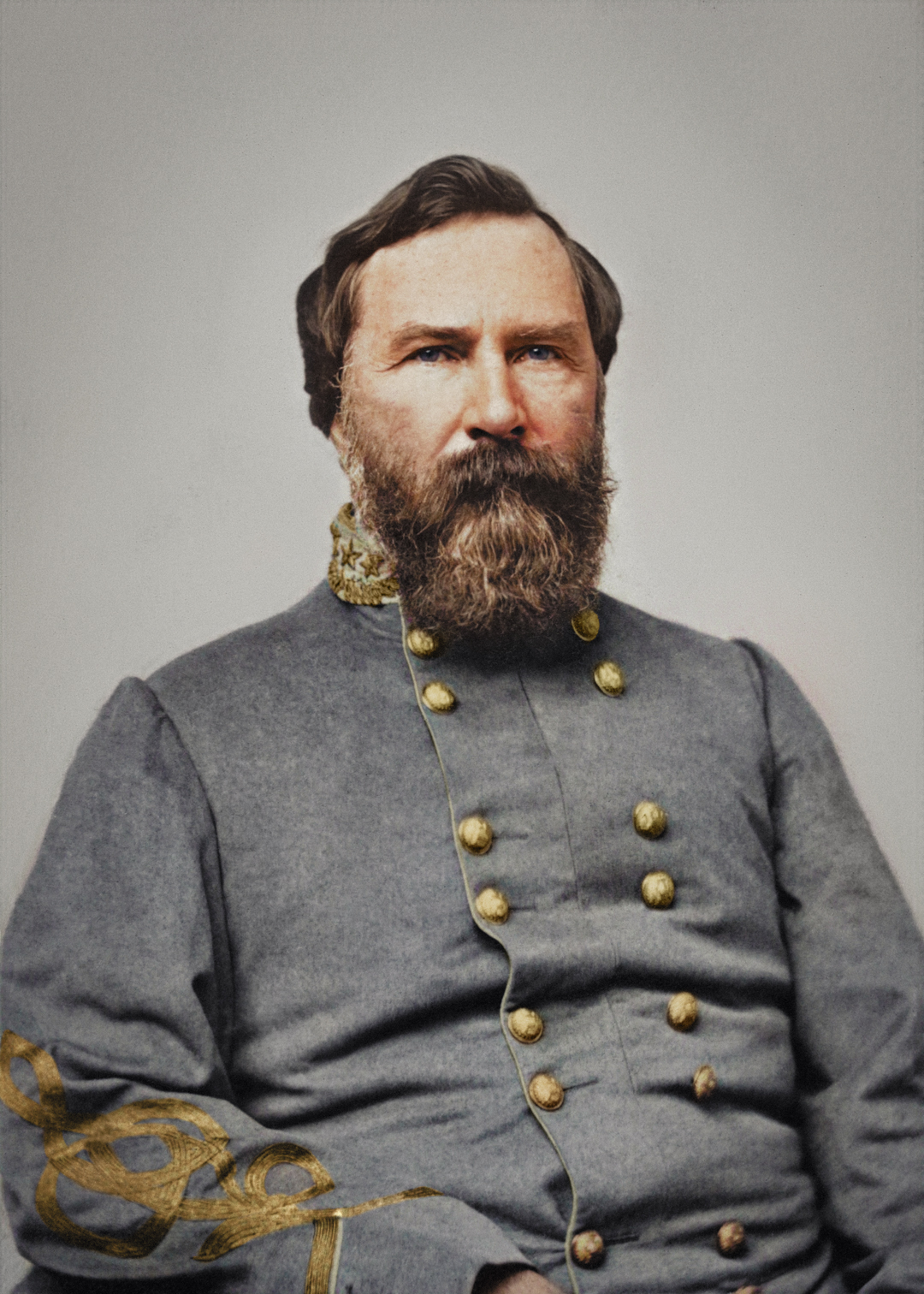

Jeremy Martin: The sounds coming from under the thick fog, to some, were, “like the distant hum of myriads of bees.”1 Burnside, having 123,000 Union soldiers at his disposal, decided to split his army in two, and attack Confederate Major General James Longstreet and Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s positions along two fronts.

Longstreet was stationed on Marye’s Heights along a thick stone wall. The Heights were heavily defended, with Confederates filling the stone wall three lines deep.

At approximately 10am, Union forces began moving west to assail Marye’s Heights. Cannons from Stafford Heights began to let loose, firing on Confederate positions.

The Tide Rises

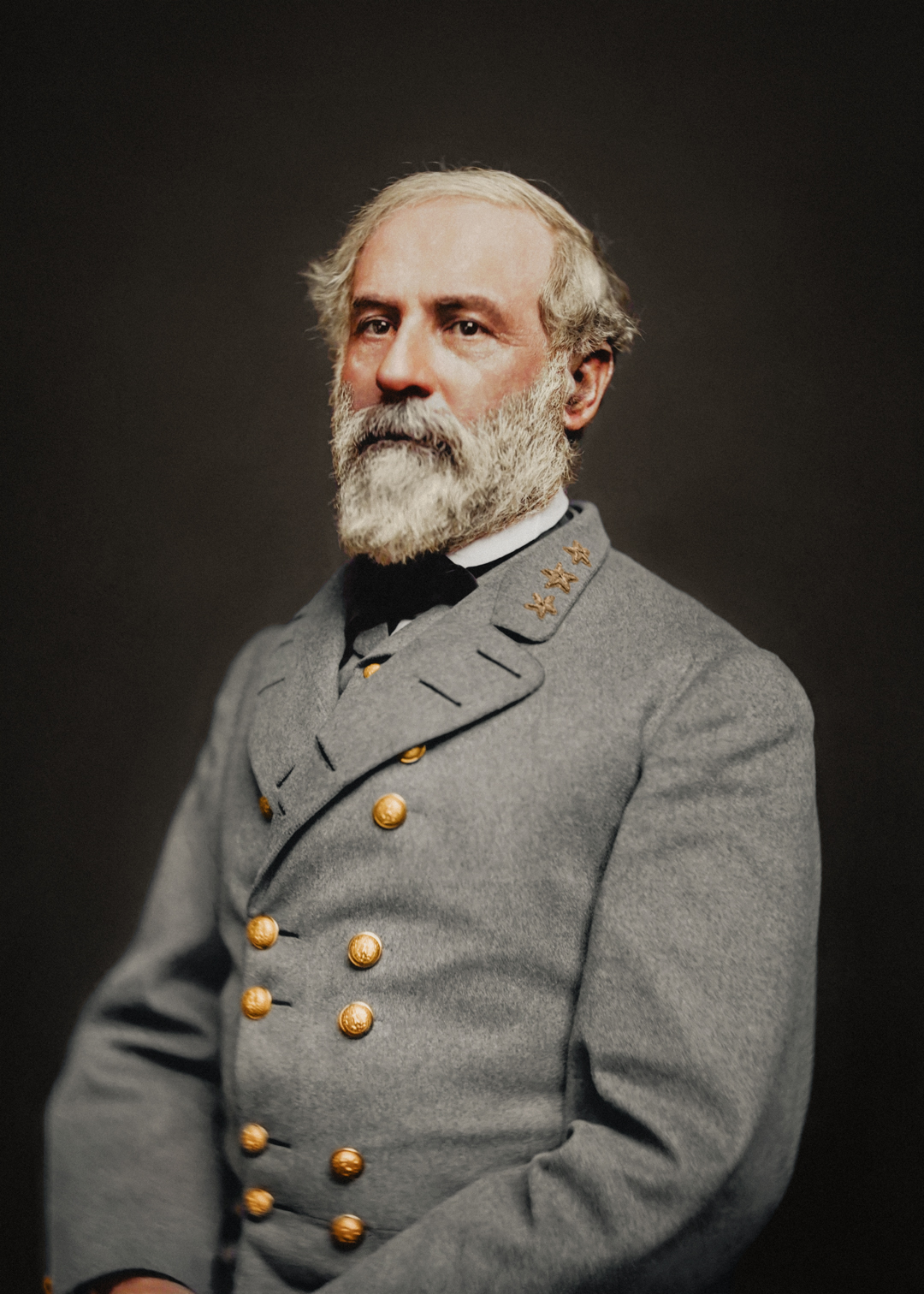

Robert E. Lee – commander of the Army of Northern Virginia – instructed Longstreet to fire the Confederate cannons onto the Federal positions. The booming of artillery from both sides of the small Virginia town shook the earth.

While the fog had lifted, a new fog began to fill the battlefield – the fog of war. After about an hour of bombardment from each side, at 11:30am, Union infantry began to make haste up towards Marye’s Heights. The mass push of Federals almost resembled a flood of water rushing towards the rebels that took cover behind the stone wall.

Union divisions led by Major General Edwin V. Sumner relentlessly charged Confederates positioned on the Heights. However, as the Union gained more ground, they came across a canal, and were forced to cross in single file, forced into a bottleneck. Quickly realizing that the position on Marye’s Heights was too heavily fortified, more Union divisions began to pour into the area.

Colonel Thomas Francis Meagher, the commander of the Union's Irish Brigade, catapulted his men into action. With sprigs of boxwood decorating their hats, the Irish brigade charged relentlessly, losing almost 600 men. In the initial assaults, thirty-two brigades charged up to Marye’s Heights, all to be beaten back by the impregnable position held at the stone wall. In total, approximately 6,000 Union soldiers were either killed, wounded, or missing. Such massive loss of life made the ground leading up to Marye’s Heights look like a sea of blue and red. Robert E. Lee himself commented, “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it.”

The following abridged recollections are from two soldiers that were present on opposite sides of the battle. The first, a Union soldier from the 24th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry Regiment witnessed multiple waves of attacks on Marye’s Heights. The second, a Confederate States Captain, witnessed the carnage from above them.

Ben

Private Benjamin Borton experienced some of the most brutal fighting at Fredericksburg. His regiment, the 24th New Jersey, was at the vanguard of the assault. The only regiments around Benjamin and his comrades were those to his left and right. Borton’s very human account illustrates his own disillusionment to the spirit of war, and comes to the realization that these men are all sons, brothers, and fathers. Surely, the horrors of Fredericksburg haunted him in his lifetime. Thoughts of survivor’s guilt, coupled with what modern health officials call post traumatic stress disorder likely plagued Benjamin.

The city was enveloped in a heavy fog, which did not lift, if my recollection is clear, until ten o'clock or later. As far as we could see in either direction stood a continuous line of soldiers in readiness to start to the field of action. Mounted officers and orderlies were continually passing back and forth along the lines, while some of the regimental officers and privates, tired of standing in the ranks, dropped out and sought a seat upon the curb or a near-by door step.

The most lively fellows mimicked the whizzing noise of an occasional round shot or shell in its arched flight high over the housetops, or cracked jokes with their comrades. Presently is heard the command, "Attention !" Every lounger springs to his place. We are ordered to prime. Every musket is raised and every man caps his piece. Our Colonel made some remarks, telling us to shoot low and try to wound a man in preference to killing him. Noticing a red colored scarf about my neck, he ordered me to take it off, saying it would make a good target for the enemy. The scarf disappeared. Suspense is intense.

Finally, the long-expected, much-dreaded command, "Forward!" is passed from officer to officer standing at the head of their Companies. With an ominous silence akin to a funeral procession. General Kimball began the perilous march down Caroline Street by leading French's First Brigade, with the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-eighth New Jersey in the center. Seventh Virginia [Union] on the right and the Fourteenth Indiana on the left.

Reaching what I will call Railroad Avenue, the column filed to the right and out that thorough- fare to begin the attack. I think I am telling the plain truth when I say that during that short march many of those men silently offered up to the Almighty their last prayer on earth. Our regiment was about to receive its first baptism of fire, and every one knew it.

My feelings in that trying moment cannot be described. Oh, I thought, why this shedding of blood? Why should brother take his brother's life? Under this impression, I instinctively cast a look upward to see if I could not behold a winged messenger of peace. But no; the sea of bristling bayonets moved on. Shells and solid shot from the enemy's heavy guns now came crashing through brick walls, and pounded in the street around about us. The first wounded man I saw was hurrying down the sidewalk with one hand pressed, against a wound in his breast, inquiring for a hospital.

Val

Confederate States Army Captain Valerius Cincinnatus Giles's account of Fredericksburg is one of awe. While Giles’ regiment, the 4th Texas, was not directly in the fighting, what he saw as a result of the fighting on Marye’s Heights haunted him. Acting almost as a bystander of the battle, Giles’ depiction of Union soldiers laying on the fields of Fredericksburg was some of the most concentrated and grotesque fighting that had taken place in the war up until that point.

From our position we had a splendid view of the battle. The heavy fighting was below Hamilton's crossing to our right and on Marye's and Willis' Hills on our left. My regiment never fired a gun and only lost one man. A young man named Worsham, of Company E, ventured down town during the bombardment and was killed by the explosion of a shell.

We saw Franklin's splendid division of Federal troops start on that forlorn hope against Marye's and Willis' Hills , four long, dark blue columns, with ‘Old Glory' proudly waving over every regiment, their bright guns flashing in the sunlight of that midwinter day. The first column moved steadily on, as if going on dress parade instead of to a sure death.

The Confederate batteries along the crest of the ridge were silent, but it was only that silence which precedes the storm. When the first column reached a point about six hundred yards from the lines, the batteries opened simultaneously as though fired by a flash of electricity. The roar of musketry joined the bellowing artillery and the whole earth trembled.

In a few moments the scene before us was enveloped in smoke, and we could see nothing but a seething, roaring crater of smoke and fire; 'splendid murder' reigned supreme there. “It was that character of murder that the world applauded at the time, but now, after the lapse of more than three decades, a few silver haired old mothers scattered all over this Union, in the twilight of the evening or stillness of the night, think of the noble boys who fell at Fredericksburg, long since forgotten by the busy world. Napoleon, Wellington and Grant were great, for 'one murder makes a villain, a million make a hero. Colonel John T. Crisp, of Missouri, in making a speech to his regiment eulogizing the memory of General A. Sidney Johnston, wound up by saying: 'It is glorious to die for one's country, but I would rather be John T. Crisp alive than General A. Sidney Johnston dead.

Six times the Federal infantry stormed that fatal Gibraltar; six times they were driven back, torn, bleeding and dying.

Kimball’s Charge

Union Brigadier General Nathan Kimball was at the vanguard of attack on December 13. Kimball’s outfit was nicknamed “The Gibraltar Brigade” for its valor and resolution in the face of overwhelming forces in the Bloody Lane at the Battle of Antietam. On the morning of December 13, however, Kimball and his Gibraltar Brigade would be put to the test once again. Under Major General William French’s Third Division, Kimball valiantly led the 1st Brigade into the fray, the first to face off against the entrenched rebels taking cover behind the stone wall.

Suffering harrowing loses, the Gibraltar Brigade was forced to retreat and allow for other divisions to try and shake the rebels loose from the position. Kimball himself was wounded in the thigh, and remained out of service to recover from his wound until the Spring of 1863. Many soldiers, however, like Benjamin, were forced to remain in the hell-storm, either wounded or trying to find a way back to safety.

Ben

At the edge of the town we passed General Kimball facing us, in his saddle, who addressed his men in these words, which I never forgot:

“Cheer up, my hearties! Cheer up! This is something we must all get used to. Remember, this brigade has never been whipped, and don't let it be whipped to-day.”

No wild hurrah went up in response. Every face wore an expression of seriousness and dread. A minute later we realized the awful danger before us, but General Kimball's men courageously faced it. A few steps further and we are out of the town, in the open fields, in full view of the enemy. To facilitate our progress in the charge, haversacks and blankets are now thrown away. The company commanders shout sharply to their men to keep the regiments in line as they advance to the attack.

Screeching like demons in the air, solid shot, shrapnel and shells from the batteries on the hills strike the ground in front of us, behind us, and cut gaps in the ranks. See there! A field officer has been struck by one of the missiles and a couple of men who have raised him to his feet are calling loudly for more help to get him off the field. As the line advances up the slope, men wounded and dead drop from the ranks.

It is not every man that can face danger like this. I saw a few so overcome by fear that they fell prostrate upon the ground as if dead. I have seen men drop upon their knees and pray loudly for deliverance, when courage and bravery, not supplication, was the duty of the moment.

Hark! There's one of my comrades, Johnny Brayerton, praying, too, perhaps for the first time in his life. It was a short one: "Oh, Lord, dear, good Lord!" he cried.

But Johnny at that trying moment was as brave as he was devout, and kept his place in the front rank. Not a gun was fired, if I remember correctly, until the brigade reached the crest of the hill, when, like a burst of thunder, the roar of musketry became almost deafening. It seemed to me every soldier, after firing his piece, had thrown himself flat upon the ground to avoid the enemy's bullets, and I did not see how I could possibly load and fire by lying down in that crouching column of men. To stand up boldly along that firing line — the dead line — was almost certain death, so I ran to a blacksmith shop some distance to my right, where, with a number of other soldiers who had taken refuge there, we banged away at the rebels; but they were so securely and safely entrenched behind a great stone wall, that I believe every man in the firing line felt that there was no hope of a victory. But we were there to fight, and continued shooting at our unseen foes.

The little frame building from which we were firing was by no means bullet-proof, yet we felt much safer there than standing out in full view of the enemy. Down goes one of our party, shot through the head.

I know not for what reason, but I stopped firing a few moments, and stood over the lifeless form of the unknown soldier with a sort of fascination, wondering who he could be; wondering what mother's boy had been added to the roll of the dead.

Just then Colonel Robertson joined us for a few minutes, and noticing the dead body of the man lying at our feet, asked who it was. Nobody knew. The Colonel then ordered a couple of men to place the body by the side of the shop out of the way of charging troops.

“There they come!” some one shouted, and looting back toward the city, we saw another long line of reinforcements charging up the slope. Lustily they were cheered as they advanced, and I noticed a wounded man sitting upon the ground waving his cap and cheering with the rest. Until nightfall, brigade after brigade charged across that field of death, to the dead-line, only to suffer disaster and defeat.

A large white dog is capering and leaping ahead of the column. My eyes follow another brigade advancing across the plain. They are veterans. The line keeps well dressed, but the men are bending as low as they can travel, and the color-bearers trailing their flags on the ground. Those heroic men are trying to avoid the Confederate bullets, but many in the ranks never took part in another fight…The cool conduct of their Colonel attracted the attention of a few, and some cried out: “That's the way for a Colonel to bring in his men.”

Some of the boys were jolly and laughing when they passed us, in close column, by the blacksmith shop, out of sight. See! Some of them are already returning — I mean those that are wounded — to secure shelter along with us in front of the building. Two stalwart fellows came around the corner, dragging their dying Colonel riddled with bullets. That regiment must have been literally cut to pieces.

General Kimball's brigade held its position at the firing-line until relieved, but even then the men could not safely retire. The only alternative was to lie at fall length upon the ground, skulk into or behind neighboring buildings, or, at much greater risk of being shot down, withdraw to the rear. While at the brick house, looking around about me upon the awful scene of carnage, a bullet grazed my head. I watched a brigade charge up the slope, close to our left, but the brave men, unable to withstand the withering fire, soon fell back in disorder, followed by soldiers who had been at the dead-line since the first attack by Kimball's men. With a number of others, in the mixed throng collected in front of the brick building, the writer withdrew from the field... I saw a shell explode, close to the heels of a large man fleeing for his life. He was blown clear from the ground, falling in a heap, frightfully mangled. A little further on, another unfortunate fellow was lying on the ground, in a violent death struggle. At the edge of the town, two men were helping off the field a badly-wounded comrade, who was cursing in a frenzy of anger and vowing vengeance upon the rebels. A couple of stretcher carriers were carrying to the hospital a man with both legs shot away. It was a sickening sight. Scenes such as I have described made a lasting impression upon my memory.

The Dying and the Dead

Around 3pm, Union intelligence reported that the Confederates were shifting within their lines, which led junior and senior staff to believe that the rebels were finally retreating. To investigate these reports, Union Brigadier General Andrew A. Humphreys of Major General Daniel Butterfield’s V Corps was sent to attack and further dislodge the rebels. In reality, however, Confederate Major Generals George E. Pickett and John B. Hood were sent from the south to reinforce Marye’s Heights.

As a last-ditch effort, Humphreys led his men up towards Marye’s Heights. As his men began to charge, wounded soldiers grabbed at soldier’s legs begging them not to attack unless they hoped to suffer the same fate. This caused Humphreys’ troops to become disorganized, and when the soldiers marched within fifty yards (forty-six metres) of Marye’s Heights, they were gunned down by a tight volley of rebel fire.

By 6pm, the fighting came to a conclusion. Unbeknownst to everyone, the bulk of the fighting was over. All that remained were the thousands of dead and wounded soldiers on the killing fields of Fredericksburg.

Ben

When darkness closed the conflict, the scattered and shattered regiments made their way back to the city, as the long ambulance train moved out on the field to take is the wounded. All next day — Sunday — men were inquiring for their Companies, and visiting the hospitals in search of missing comrades. Meeting Captain Hancock on the street, he conducted me to one of the hospitals to see our color-bearer. Corporal Kelley. Lying upon the floor of a large room, around which blood-stained soldiers laid as close as they could be crowded together, Kelley was dying.

Into churches, halls and dwellings — buildings of every sort — the wounded had been carried, where the army surgeons attended to their injuries and tried to alleviate their sufferings.

Soon after leaving the hospital I joined a remnant of my Company, quartered in a billiard saloon. As the day advanced, more of the missing came in, but some never returned. The morning after the battle, the Twenty-fourth Regiment mustered only thirty-six men.

Hundreds, who had become separated from their Companies, took shelter in cellars, basements, stables, sheds, — wherever they could find a roof to cover their chilled forms from the freezing air.

Val

The next morning, before good daylight, Comrade Deering and myself stole away from our line of battle and went down in the 'valley of death,' where the fighting the day before had been the hardest. There I witnessed a scene that haunts me still. I disobeyed orders to burden my memory with the most appalling sight I ever saw before or since. The wounded had been removed, but the dead were all there. They lay in heaps, crossed and piled and in every imaginable position, all cold, rigid and stiffly frozen. We never saw one-half the battlefield, but we saw enough, and I was glad when a little, dried-up Georgia captain very peremptorily ordered us back to our command, which we reached about sun-up.

The destruction of human life was dreadful, especially on the Federal side. As General D. H. Hill sat on his horse and looked sadly at the awful scene in front of the sunken road, he remarked that nothing in modern warfare ever surpassed it, unless it was the hollow road of Ohain at Waterloo.

The Angel of Marye’s Heights

Following the carnage at Marye’s Heights, Confederates laid in wait at the stone wall on Marye’s Heights. Overnight, Confederates heard the screams and cries of wounded Union soldiers who were freezing, dehydrated, and starving. One Confederate soldier, Richard Rowland Kirkland of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry, wanted to help wounded Union and Confederate soldiers who were on the fields of Marye’s Heights.

When dawn came, it was discovered that approximately 6,000-8,000 Union soldiers were laying in the field. Kirkland requested to his commander, Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw, if he could give his men water. Reluctantly, Kershaw accepted.

When Kirkland asked if he could wave a white handkerchief, Kershaw said that he could not. Kirkland reportedly replied, “All right sir, I’ll take my chances.”

Kirkland climbed over the stone wall and gave wounded Union soldiers drinks from the canteens that he collected and filled with water. Kirkland helped all soldiers who were begging for water and did not stop helping until all soldiers were cared for. Kirkland’s actions remained legend in Fredericksburg and Kirkland was aptly named the Angel of Marye’s Heights.

Kirkland, however, could not escape the jaws of death. On September 20, 1863, less than a year after his bravery at Fredericksburg, Kirkland was killed at the Battle of Chickamauga •

This Viewfinder feature was originally published December 13, 2021.

Further Reading

Jeremy Martin: The following books offer further information on the history of the Battle of Fredericksburg. Some books are on general Civil War history, but offer sections on the Battle of Fredericksburg. These books help further dissect and digest the battle further.

⇲ The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian by Shelby Foote (Vintage Books, November 1986)

⇲ Simply Murder: The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862 by Chris Mackowski & Kristopher D. White (Savas Beatie, 2013)

⇲ A Worse Place Than Hell: How the Civil War Battle of Fredericksburg Changed a Nation by John Matteson (W. W. Norton & Company, February 2021)

⇲ Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! (Civil War America) by George C. Rable (The University of North Carolina Press, November 2009)

Rags and hope; the recollections of Val C. Giles, four years with Hood's Brigade, Fourth Texas Infantry, 1861-1865 by Valerius Cincinnatus Giles (New York, Coward-McCann, 1961)

⇲ Reminiscences of the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment by John G. B. Adams (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1899)

⇲ On the parallels; or, Chapters of inner history; a story of the Rappahannock, by Benjamin Borton, (Woodstown, N.J.,Monitor-Register Print, 1903)

More

The Battle of Fredericksburg – Crossing the Rappahannock

Illustrated eyewitness accounts of the Union's amphibious assault of Fredericksburg on Thursday, December 11th, 1862

This description is from ⇲ The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian by Shelby Foote (Vintage Books, November 1986) ↩

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store