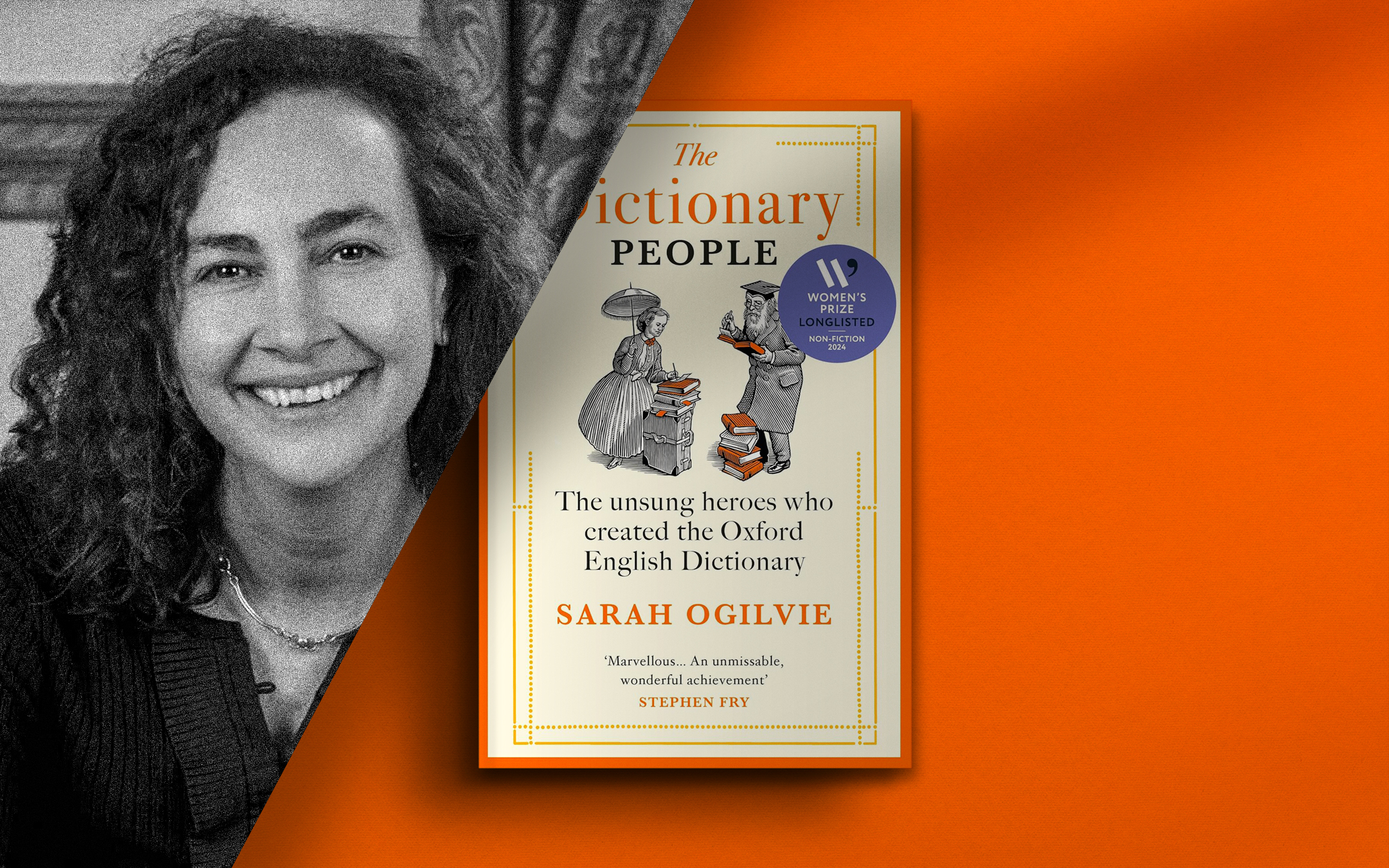

The Dictionary People with Sarah Ogilvie

Sarah Ogilvie on the personalities behind the pages

The Victorian Age was a time of colossal projects. Alongside the bridges and railways, though, we should remember the great enterprises of the mind.

The Oxford English Dictionary, begun in 1857, is an ideal example of one of these. As Sarah Ogilvie, author of The Dictionary People, explains, it took the combined efforts of thousands of contributors more than seven decades to complete.

In this interview she tells us more about 'the Wikipedia of the nineteenth century'.

Questions by Peter Moore

Unseen Histories

You worked at the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) yourself. Can you tell us a little about this experience?

Sarah Ogilvie

When I was working as a lexicographer at the OED, I specialised in words coming into English from outside Europe — these make up a surprisingly significant proportion of the English language! We often forget that words such as 'shampoo', 'barbecue', and 'chocolate' originally came into English from other languages.

Unseen Histories

A decade ago you made an extraordinary archival discovery that set you on the way to writing your new book, The Dictionary People: the unsung heroes who created the Oxford English Dictionary, can you tell us about that?

Sarah Ogilvie

This book has been quite a journey. The Oxford English Dictionary was a crowd-sourced project, the Wikipedia of the nineteenth century. And I always wondered who these people were. I think of them as the unsung heroes of the OED — without them reading their local books and sending in their local words, the Dictionary could never have been written.

A decade ago, I was in the archives of the OED and came across a small black book tied with cream ribbon containing the names and addresses of the people who helped create the Dictionary.

Unseen Histories

Can you tell us more about the author of this little black book?

Sarah Ogilvie

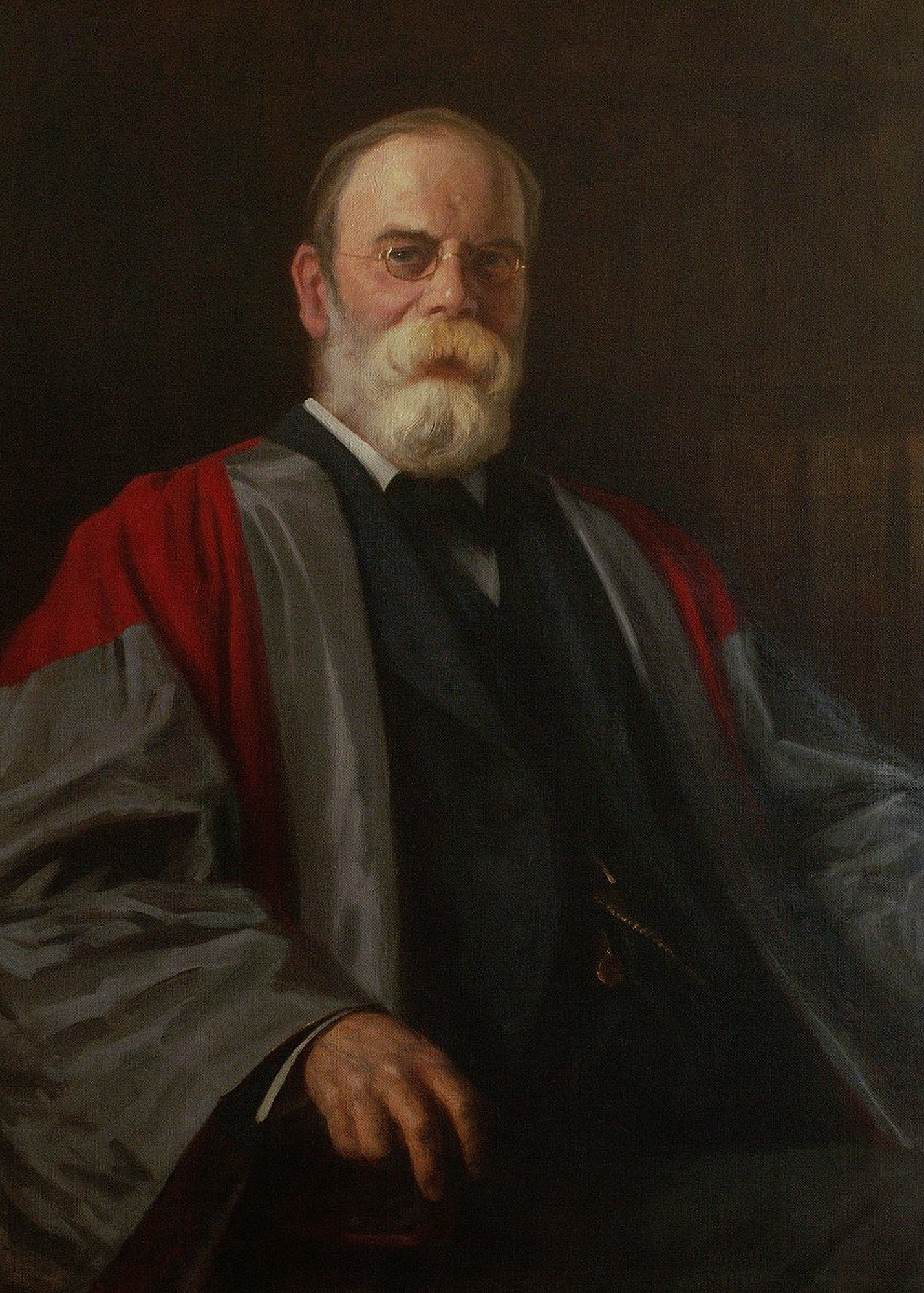

The little black book turned out to be the 150-year-old address book of James Murray, the longest-serving editor. He corresponded with all these people — 3000 of them! Royal Mail had to put a red pillar box outside his house in north Oxford to cope with all the post (it is still there). Murray started working on the Dictionary in 1879 and devoted his life to it. He died in 1915 while working on the letter 'T', not knowing if the Dictionary would ever be finished (it was, 13 years later).

Unseen Histories

How did Murray recruit his huge, global network of 3,000 volunteers?

Sarah Ogilvie

He put advertisements in newspapers and magazines and spread the word through clubs and societies.

Unseen Histories

These contributors are a hugely varied and colourful crew. Can you tell us about some of your favourites?

Sarah Ogilvie

There are many incredible people in the book from a pornography collector and three murderers to a cocaine addict and a vegetarian vicar! There were a lot more women than we thought. One young woman, Margaret Murray, sent in words from Calcutta and ended up being one of the first female Egyptologists. Her story is told in the chapter ‘A for Archaeologist’.

Another woman in Philadelphia, Anna Thorpe Wetherill, was an anti-slavery activist; she stars in chapter ‘W for Women’. Then there is Joseph Wright in chapter ‘O for Outsiders’, who is in a league of his own. He started out as a donkey boy, aged six, in a Yorkshire mine. He could not read until he was 15 years old but ended up a professor at Oxford — his story probably inspired me the most, I got a real sense of his gentleness and good humour, and his brilliance of course.

Unseen Histories

What did the contributors receive in return for their efforts?

Sarah Ogilvie

This was a big question for me while writing the book. What motivated these people to give so generously of their time and effort for no payment?

Sometimes they got a mention in the preface of a portion of the Dictionary as it was gradually published from 1884 to 1928. Sometimes they were thanked by James Murray in one of the speeches he gave to the London Philological Society. But most often their work was not explicitly credited, so I can only presume they did it because they believed in the aims of the project to document and describe every word in the English language. Many of them were autodidacts; they were generally not the scholarly elites. The project gave them access to an intellectual world otherwise denied to them.

Unseen Histories

The process of compilation took a very long time. Can you tell us about this time frame and whether the progress came at an even pace or in fits and starts?

Sarah Ogilvie

The OED began in 1857 and took 71 years to complete. It got off to a slow start, but James Murray was a master manager of the project so after he took over as chief editor in 1879, it progressed steadily.

Unseen Histories

We think of the Victorian Era as a time of expansion and ambition. Does the OED fit into this broader historical narrative or do you see it more as an idiosyncratic enterprise?

Sarah Ogilvie

The OED was prototypically Victorian in the scale of its scope and ambition.

Unseen Histories

You have structured The Dictionary People in an inventive way, moving through the alphabet in brisk chapters. Where did this playful idea come from?

Sarah Ogilvie

For a long time, I pondered how to structure the book. There were so many people, so many stories. How could I show the huge diversity of contributors while at the same time telling a single narrative and giving the reader an intimate sense of the lives of the dictionary people?

Then a solution came to me: just as Murray had broken his gargantuan task down into letters of the alphabet, I would use the alphabet to tell my story. So there are 26 chapters, one for each letter of the alphabet •

This interview was originally published September 27, 2023

As a technologist she has worked in Silicon Valley at Lab 126, Amazon's innovation lab, where she was part of the team that developed the Kindle. She originally studied computer science and mathematics before taking her doctorate in Linguistics at the University of Oxford, and then taught at Cambridge and Stanford.

The Dictionary People: The unsung heroes who created the Oxford English Dictionary

Chatto & Windus, 7 September, 2023

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-1784744939

“[An] astonishing book” – Sunday Times

What do three murderers, Karl Marx's daughter and a vegetarian vicar have in common?

They all helped create the Oxford English Dictionary.

The Oxford English Dictionary has long been associated with elite institutions and Victorian men. But the Dictionary didn't just belong to the experts; it relied on contributions from members of the public. By 1928, its 414,825 entries had been crowdsourced from a surprising and diverse group of people, from astronomers to murderers, naturists, pornographers, suffragists and queer couples.

Lexicographer Sarah Ogilvie dives deep into previously untapped archives to tell a people's history of the OED. Here, she reveals, for the first time, the full story of the making of one of the most famous books in the world - and celebrates the extraordinary efforts of the Dictionary People.

“I have not been able to put The Dictionary People down ... I completely love it”

– Joanna Lumley

“Enthralling and exuberant ... Here is a wonder-book for word-lovers”

– Jeanette Winterson

“Marvellous, witty and wholly original”

– Alan Rusbridger

With thanks to Jessie Spivey.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store