The Eiffel Tower: The Beauty and the Terror (1888)

The Parisian skyline was changing in a strange and stirring way in July 1888 when Gustave Eiffel led a tour of his majestic new tower

For the first time Parisians began to appreciate the size of Gustave Eiffel's new tower in the summer of 1888. A year and a half after construction begun, upwards progress was now coming at impressive speed.

Eiffel's 'tower' was intended to be the centrepiece for the planned Paris Exhibition of 1889. With less than a year to go, in July 1888, it had reached a height of around 360 feet as the second stage was completed.

The most notable feature of the tower was its sheer size. 'My tower will be the tallest edifice ever erected by man', Eiffel had proclaimed. Another characteristic, though, was becoming more evident by the summer of 1888.

This was its colour. It had been decided, after much experimentation, to paint the tower a dusky red. The advantage of this was that, at sunset, the tower would assume a golden sheen.

That July the photographer Roger Viollet captured the workers' progress. The red stood out sharply, not just in the glow of sunset, but also in the haze of an overcast Parisian day.

Viollet photographed an intriguing scene at a poised moment. Although it was still unfinished, the tower played its first part of public life that July. On Bastille Day it was used as the platform for a lavish fireworks display.

'Cascades of blue, red, green and golden stars issued from the top of the Tower', wrote one observer, 'followed by torrents of flames, which in the dark night made the Tower look like an incandescent volcano'.

These fireworks came at a time when many were still making up their minds about the tower. Was it inspiring or was it ludicrous? Just one thing was certain.

No one on Earth had ever seen anything like it before.

As the year 1888 began, the Champ de Mars in Paris presented a strange sight. Strewn across it were gigantic lengths of iron shaft and the whole area teemed with noise and workmen. This was a small area of ground, but over the past year it had become the subject of debate the world over. Ever since the great concrete foundation slabs had been set in place the year before, the 'stupendous' construction had been rising steadily higher. Among many there was genuine excitement.

29 January 1888

The tower stands firmly planted, work on it is being rapidly pushed, and there is no doubt that, when completed, in due time, the work will redound to the credit of the energetic man whose name it bears.

But not everyone had quite so rosy a view. During the planning phase Eiffel had encountered derision from artists and writers and others complained that too much money was being spent on the project. What was it for? And at what human cost was it being built?

Gossip, repeated on both sides of the Atlantic held that two hundred people had already died during its construction and that it was structurally unsound. The stonework of the foundation was rumoured to have settled dangerously, that the props holding the heavy iron beams in place had given way, and that, in short, the whole tower was already listing over in preparation for some imminent catastrophe.

None of this was, in fact, true. But important lessons were being learned by those leading the project. The tower was such a novel thing - such an ambitious idea - that the public needed to be told with clarity and regularity about its progress and purpose.

Eiffel himself was asked to lead a private tour of the construction site for journalists in July 1888. The timing was auspicious. Shortly before the builders had reached the second platform and there were plans to use the tower as part of the Bastille Day celebrations.

The result. however, was unsettling.

7 July 1888

M. Eiffel, with an eye to the main chance, kindly invited the reporters of Paris for a tour of inspection.

They went, and were sumptuously entertained to begin with. Thereafter, the ingenious architect led the way up the vast spiral staircase of 180 feet, the reporters cautiously trooping after him. At the first landing place, several of the number became faint hearted, and stopped in the ascent; and at the top of the second flight they all refused to go an inch further.

The reason given was that they were giddy. This painful incident, says M. Eiffel, is explained by the fact that the pressmen had all diner before making the ascent. Probably the public will not put their own construction on that explanation. It will be rather awkward if the sightseers of Paris, before mounting the famous tower they have crowed over so exultingly, have to abstain from dinner; and still more so will it be if they have to make preparations akin to those undertaken before starting on a voyage.

What will be the remedy for tower sickness, we wonder? Will brandy and soda be the specific recommended? Will fat boiled pork prove effective as oil on troubled waters? Will each weary climber clinging to the rails with one hand, have with the other to hold to his wan lips a juicy lemon?

Or will the infallible remedy be the oft-tried, yet much mocked red herring? Who can tell? The terrors of sea-sickness are now threatened by a dangerous rival.

If, as it is rumoured, the Eiffel Tower engages at its lofty pinnacle in a kind of pendulum swing of several yards in extent, the experiences of those who reach the topmost platform will be even worse than those of the land-lubber in a choppy sea.

This experience caused a little consternation. Had Paris placed all its hopes on a structure that simply made people ill? There had been similar worries about the effect of speed on the human body, as railways carried humans across distance more quickly than ever before. Now Eiffel was asking people to climb upwards. Could they tolerate this?

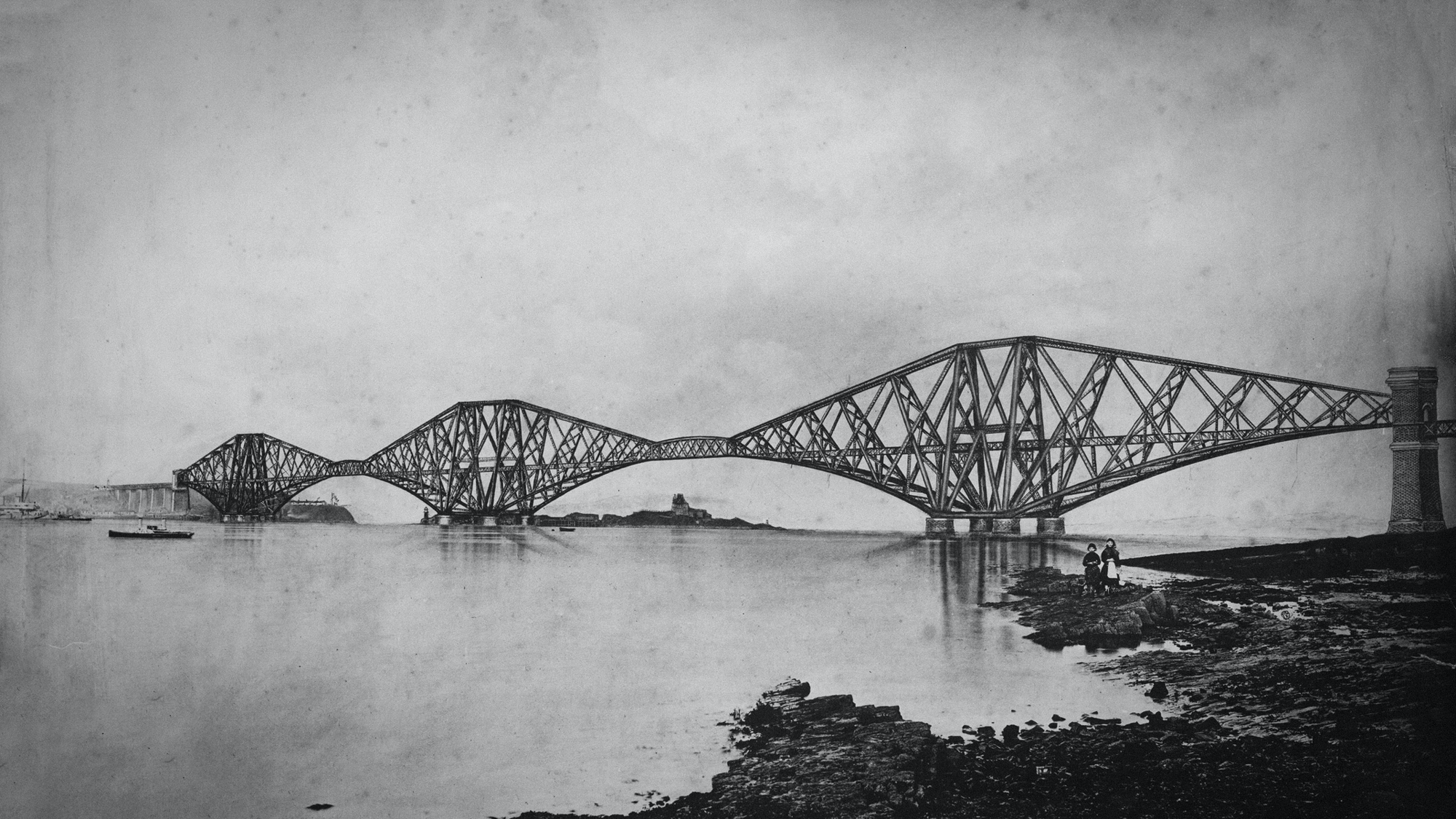

Only time would tell. What was known with more certainty was that the tower was a marvel of civil engineering. Over the past generations Great Britain had had Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his ships and tunnels and bridges. But even Brunel had not attempted something like this. And never had he worked in so prominent a public location.

Throughout the early part of 1888, Eiffel's tower (its name remained unsettled at this point in its life) was spoken of as the second wonder of the modern world. The first in the eyes of many was the iron bridge over the Firth of Forth in Scotland with its glorious succession of arches. Both of them showed the 'power of man over space'.

This idea - of progress and power - was one that European nations like France, Britain and Germany were attempting to project. And the Paris Exhibition of 1889 presented the French with a glorious opportunity for displaying what they could accomplish.

Everyone watched as the tower rose over the first half of 1888. 'M. Eiffel's 'Tower of Babel', commented one who visited the site in May, 'is rising steadily and the enormous mass of iron which the constructors have already piled up against the clouds is the amazement of everybody'.

12 May 1888

When you stand at the base of the gigantic monument and look up to the skies through a colossal spider’s web of red metal, the whole thing strikes you as being one of the most daring attempted since the Biblical days when the real Babel was planned.

Eiffel's tour for the journalists might not have gone well in July, but everyone agreed that the Bastille Day celebrations had been something else. At a quarter to ten at night, those in the centre of Paris had turned their eyes 'in delightful expectation' towards the half-built tower. People stood in the streets; many clambered out on to their rooftops, seeking the best view.

As they gazed as one towards the tower and the jets of colourful light that exploded over it, Parisians discovered for the first time in their history that they had a new focal point. The psychogeography of their ancient capital had shifted in a meaningful way.

While this raised hopes for the tower's future, the British remained predictably sniffy. A long dispatch was featured in the Times of London in the days after the fireworks, prompted by another of Eiffel's private tours:

6 August 1888

M. Eiffel, the engineer and constructor of the hideous tower which, if public taste does not sooner secure its condemnation, is destined for years to disfigure a whole quarter of Paris, entertained to-day the Parisian journalists at breakfas

His guests met on the first storey of the edifice, at a height of 60 metres. Doubtless they kept cool and collected, or otherwise the descend by a narrow winding staircase might have become a real danger.

The object of the breakfast naturally was to direct the attention of the press to the beauty of the conception, which consists in placing a tower 300 meters high in a hollow, and in dwarfing by its exaggerated dimensions the normal proportions of the other exhibition buildings ...

M. Eiffel is the author of [several] useful inventions, but nothing he has done has brought him such reputation as the hideous iron maypole which he is about to erect to outrage the good taste of the Parisians. Nothing favourable can be said of its beauty, its purpose, or its use to anyone but M. Eiffel and to the others interested in this undertaking, which the Republic has had the bad taste to subsidise.

It has spread the name of its constructor to the ends of the earth. It will continue to exasperate men of taste and sense, and to be an eyesore to all who live in or visit Paris when Gen. Boulanger, and even Sarah Bernhardt have been long forgotten.

I shall continue to say this until I meet some one who can give me a satisfactory explanation of the purpose of this metallic monstrosity. It certainly is not being constructed for the purpose of giving breakfasts upon it at a height of 200 metres.

It is not being built for astronomical observations. If it had been so designed it would have been placed, not in a hollow, but on a hill. It is not constructed to prove that an iron framework of 300 metres long can be made to form one solid fabric. It will not benefit the exhibition, for it does not help to show off the exhibits, and indeed it can benefit nobody but M. Eiffel himself.

Such sourness was perhaps to be expected, given the fierce nationalism of the age and the novelty of the tower. But it had little bearing on a project that continued to develop at pace throughout the autumn months of 1888.

By the end of the year the construction had reached beyond 600 feet. This, it was cheerfully pointed out, made the tower considerably taller than any other structure on the planet.

For centuries the Pyramids of Giza had held this position. Now their height of 513 feet was beginning to look quite modest, as were the steeples at Cologne, Antwerp or Strasbourg. In Britain, meanwhile, the tallest building remained Salisbury Cathedral, built in the thirteenth-century.

‘Its true proportions will be better realised’, remarked one impressed journalist, ‘by reflecting that it is three times as high as the Monument on Fish Street Hill, and more than four times as lofty as the pedestal from which Nelson’s effigy looks down upon Trafalgar Square’.

By the start of April 1889, a month before the opening of the Paris Exhibition, the tower was finished. 'M. Eiffel', wrote one correspondent, 'is decidedly the hero of the day and his name is on nearly everybody’s lips. 𖨠

3 April 1889

Although for the past twelvemonth his colossal Tower has been a bore to many, nevertheless general attention is now concentrated upon it, and crowds of Parisians of every grade went out to the Champ de Mars or the Trocadero during the afternoon in order to see the French tricolour floating from the cage-like summit of the Modern Babel.

On both banks of the river the eager crowds collected to gaze upon what was called originally a ‘Metallurgical Monstrosity; but is now termed a ‘Nineteenth Century wonder.