The Kingdom of Fife

Louis D. Hall investigates the history of his homeland

Having recently published his account of a horseback journey across Europe, In Green, this summer the author Louis D. Hall set out to explore the history of a more familiar landscape.

Hall grew up in Fife, north of Edinburgh, an enchanting place of hills, estuaries and coasts. But until recently he had not investigated the kingdom's rich history.

Setting out on foot he discovered stories of adventurers and witches, saints and scholars.

It was when the field was gone, the wood had been dismantled and the land razed that I first began to panic; housing developments shooting up, farms selling out, roads widening, progress carving its concrete path. My home was changing beyond recognition.

To many, Fife is that thoroughfare beyond Edinburgh, the necessary route to Perthshire and the Highlands. A peninsula bordered by the Firth of Tay to the north, the North Sea to the east, and the Firth of the Forth to the south; it is notorious for the red oxide Forth Rail Bridge, and the newly erected Queensferry Crossing.

Further afield, Fife is known for St Andrews – the home of golf, the oldest university in Scotland, and its twelfth-century abbey – while locally, it is heralded by the ‘East Neuk’ coastline, a prime spot for weekend breaks and second homes.

Indeed, as King James IV once commented, Fife is a ‘beggar’s mantle fringed with gold.’ Beyond the surface, however, underneath the ever-spreading cement of new housing, Fife is a wellspring of history, some 512 square miles in size: a county, a kingdom and a home.

This summer I set out to discover a landscape rapidly transforming. With the certainty of my childhood being lost forever – the field, the wood, the village – it dawned on me how little I actually know of Fife’s story, its long, living history.

And so, travelling west to east, from Kincardine Bridge to St Andrews, I opened my eyes, looked ahead and sought the signs that might help illustrate the past, hoping I wasn’t too late. ‘Fareweel, Bonny Scotland, I'm awa' tae Fife!’

Culross

A coracle, a witch, an admiral and Macbeth; as I was quick to discover, my journey on foot became shaped by physical clues and old tales. Piecing them together has since been the challenge.

Less than five miles from Kincardine, there is a beautiful village called Culross. Built up from the sixteenth century onwards, identifiable by its white-harled houses, ochre-coloured palace and cobbled streets, I have known it primarily for the wonderful Red Lion Pub and the wide-reaching views of the River Forth. But there is far more than what initially meets the eye.

First to the coracle. At the west side of the village there’s a little ruin. Easy to miss, it juts out from the hill next to Low Causeway Road, opposite the football park: the humble remains of St Mungo’s Chapel.

It is from these ancient stones, ones I’ve passed many times, that Fife, Glasgow, and much of Scotland owes its genesis.

Culross was founded in the sixth century by Christian missionary Saint Serf. The story goes that, adrift on a coracle after being sentenced to death by her father, a Brittonic princess arrived onto the quiet shores of Culross, exhausted, pregnant and wrongly accused of infidelity - she was raped. Teneu, later to be canonised as a saint, was promptly welcomed by Serf and invited to live in the community.

In 518, Teneu gave birth to Kentigern, later nicknamed Mungo, meaning ‘dear one.’ Under the care and tuition of Serf, Mungo soon became a favourite student. Outgrowing his jealous peers, he left the monastery and sought out a friend of Serf’s who lived near Sterling, a holy man named Fergus. The pair became close and, on his deathbed, Fergus told Mungo his dying wish: to have his body placed upon a cart and pulled by two oxen. Wherever the oxen stopped, this was to be his burial place.

Mungo carried out Fergus’ wish and travelled with the oxen until they came to a halt, close to the waters of Molendinar Burn. Mungo named this area Glas Ghu (Glasgow), meaning ‘dear green place.’ It was here that Mungo would start the first Christian community, later to become the site of Glasgow Cathedral.

For Teneu, the waters of the Firth of the Forth embodied a life-giving path to a new home. Some 800 years later, a boy was born in Culross who came to see the blue expanse before him as a gateway to the world.

Thomas Cochrane

Beyond Saint Mungo’s chapel, the market square opens up into Culross proper. Here, opposite the palace, there is a tired looking Chilean flag next to the bust statue of Lord Cochrane. Born in 1775 to an inventor father who died impoverished, the young Thomas Cochrane went to sea to regain his family’s fortune. Leaving Britain in 1818, he was recruited by the Chilean Navy and took command in their war of independence against the Spanish Colonists.

Cochrane’s efforts became legendary. Not only did he play a vital role in the Chilean success, but he helped achieve Peru’s freedom in the process. Soon after, in 1823, he was invited to command the Brazilian Navy in their fight against the Portuguese. He promptly accepted. Cochrane's feared reputation and use of audacious tactics led to the Portuguese abandoning the fight. He went on to liberate other Iberian-held ports along the Brazilian coast, effectively securing the nation's independence.

Cochrane was buried in Westminster Abbey in 1860, with the Brazilian minister offering these words: ‘We place these flowers on Lord Cochrane's grave in the name of the Brazilian Navy, which he created, and of the Brazilian nation, to whose independence and unity he rendered incomparable services.’

The Fife Witch Trials

While the water of the Forth and the stars on a clear Fife night played stage to rescue and redemption, they also triggered one of Scotland’s greatest atrocities. Leaving the shoreline behind me, I walked up the hill and found the sleepy ruin of West Kirk. From here I could see the Ochill hills rising in the north (the borderline to neighbouring Perthshire) and the behemoth Grangemouth Refinery spanning the view to the south.

In 1675, however, events were directed in a more disquieting direction. It was alleged that in the grounds of the cemetery, right where I stood, four local women would regularly meet and seek out the devil. Such stories stood behind a chilling episode in Fife’s history when, between the sixteenth and eighteenth-centuries, an estimated 380 ‘witches’ were tortured and executed – most by burning.

Accelerated by his own disfiguring diseases and religious extremism, King James VI grew convinced that the devil’s secret agents were at work. As there was no law against confession by torture in Scotland, Fife played host to the cruellest of these deaths.

In 2020, the Fife Witches Trail was forged to remember some of those women who died, ‘Innocent victims of unenlightened times.’ In nearby Torryburn, an ex-mining village three miles further along the Coastal Path, the most notorious victim of Fife’s Witch Trials is commemorated: The Torryburn Witch.

Lillias Adie, a young woman accused of having sex with the devil on cloudless nights, was tortured until she confessed. She died while awaiting trial. Adie was buried in 1704 on the mudflats of Torryburn Beach under a sandstone slab, preventing the devil reanimating her for their nighttime meetings. The only known grave of a witch in Scotland, the slab was discovered in 2014.

Macbeth

I walked north. I passed through the eighteenth century weaving village of Cairneyhill and the ex-mining village of Crossford (with agricultural settlers dating back to the Bronze Age). But witches stayed on my mind – I thought of Macbeth.

First performed in 1606, the fear of witches in Scotland was not helped by ‘The Scottish Play’. While a work of fiction, there are historical elements to Shakespeare’s play that allude to Fife’s history. In 1034 King Malcolm II of Scotland died leaving his young grandson to become King Duncan I.

Macbeth, a feared warrior and charismatic leader, was appointed by the new king as Dux (war leader). This was a grave error of judgment, an appointment that would foretell Duncan’s death. Seeking the crown for himself, in 1040 Macbeth turned against his king at the Battle of Bothnagowan, and assumed the throne.

Macbeth’s seventeen-year reign was mostly peaceful. In 1054, however, he was faced with an English invasion led by a man named Siward (immortalised by Shakespeare’s Macduff) who had previously escaped his clutches.

Macbeth was killed in 1057 by forces loyal to the future Malcolm III, and was succeeded by his stepson Lulach. His dynasty only lasted another few months after Lulach was killed in battle against Malcolm, whose descendants then ruled Scotland until the late thirteenth century. Thus the Kingdom of Fife was born.

Margaret Atheling

Some seven miles later, leaving stones and stars behind, I reached the Royal Burgh of Dunfermline – the original capital of Scotland. There, opposite Carnegie Hall, I found one of the smallest clues to Fife and Scotland’s history: the shoulder bone of Margaret Atheling.

Canonised as a saint by Pope Innocent IV in 1250, Margaret was Malcolm III’s queen consort from 1070 until her death in 1093, just four days after her husband was killed. Known throughout Europe as the ‘Pearl of Scotland’, as a devout Catholic Margaret became recognised for her pious influence on her husband, focussing on the needs of the poor, establishing Dunfermline Abbey (still a working church today), and in celebrating pilgrimages to St Andrews.

Margaret created the original ‘Queen’s Ferry’ crossing, to allow pilgrims to make their journey to the relics of Andrew the Apostle, while also promoting trade. Today Queensferry Crossing Bridge, the bustling town of South Queensferry (featured in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped) and the cobbled village of North Queensferry, are testament to one of her lasting legacies.

She also had eight children, with four of them – Edmund, Edgar, Alexander, David – becoming kings of Scotland, and one of her two daughters, Matilda, marrying Henry I of England. Along with Scottish kings, queens and Robert the Bruce, Malcolm and Margaret are buried together in Dunfermline Abbey.

East Neuk

Walking back to Fife’s shore ‘fringed with gold’, the coastal path tells a story of grit, Picts, fishing and early beginnings. With the coal mining and limestone industries prolific in the west (from the thirteenth century to the 1980s), the path will take you east through Charlestown, Limekilns, cobbled North Queensferry, metalworking Inverkeithing (first set upon by the Roman governor Agricola between 78-87 CE) and, eventually, to the Neuk - home to the first settlers.

From Dalgety Bay to St Andrews, here begins a string of fishing communities all the way round the East Neuk, where the Kingdom of Fife meets the North Sea. While some of these communities are perhaps widely recognised (Kirkaldy, once the largest linoleum manufacturer in the world; Elie, a prime holiday destination; or Anstruther, for its world famous fish and chips), there are lesser known corners that shed light on Fife’s past.

The Pict caves of Wemyss village is one such hidden gem. This site contains the largest collection of Pict inscribed symbols in Britain, with the earliest of these thought to date back to the Bronze Age. The Picts left no written language or history - all we know of them is what we are told through their symbols, with only sixty in total scattered across Scotland, from Fife to Skye.

The Wemyss Caves are home to over half of them. Despite my mantra on this walk to look ahead with eyes wide open, it becomes far too easy to miss the signs in between: a figure of a six-oared boat, a horse, an eagle, early Christian crosses. Without realising, I was travelling to Fife’s beginnings.

Running out of path, I took stock on Fife Ness – a flat land on the east of the peninsula, protruding into the North Sea. With the retreat of the ice caps, evidence of some of the earliest human occupation of mainland Scotland is to be found here, around 8,000 BCE.

It seemed a fitting place to pause my journey. Up until very recently, Scotland’s history has been largely misunderstood, forgotten or considered unimportant. Over the last thirty years the tide has changed. The Victorian tartan and shortbread facade has been breached and a deep, perhaps bottomless well of facts and fiction have illuminated a hidden past.

In a small way, I too have caught a glimpse. After setting off from Kincardine one sunny morning, afraid of what was being lost, I discovered more than I could have imagined. From the bones of saints, to the unmarked graves of star-gazing witches; quixotic escapists, inventors, Picts, caves, kings, battlegrounds and industrialists – what lies beneath the surface are layers of existence, wrapped up in moss and earth.

Some of these lives are gone forever, others have been inscribed in stone for us to learn from and uncover. This journey spurred from panic and finished in fascination. Yet the threat to Fife’s history is ever increasing. St Margaret’s Cave is under a car park; the coastal path is suffering heavy erosion; historic churches are being sold as flats; quick-build housing developments are fast cementing the natural green spaces, swallowing up the unique identities of some of the eighteen Royal Burghs.

It cannot be denied that the past is at risk of being lost, built over or untaught into extinction. But Fife is not alone in this. The needs of an increasing population are widespread and modern education seems unwavering in its demythologising standpoint, unfazed by the lore and lives that have made us who we are. To Fifers, we must explore the past, to visitors, haste ye back •

This feature was originally published September 1, 2025.

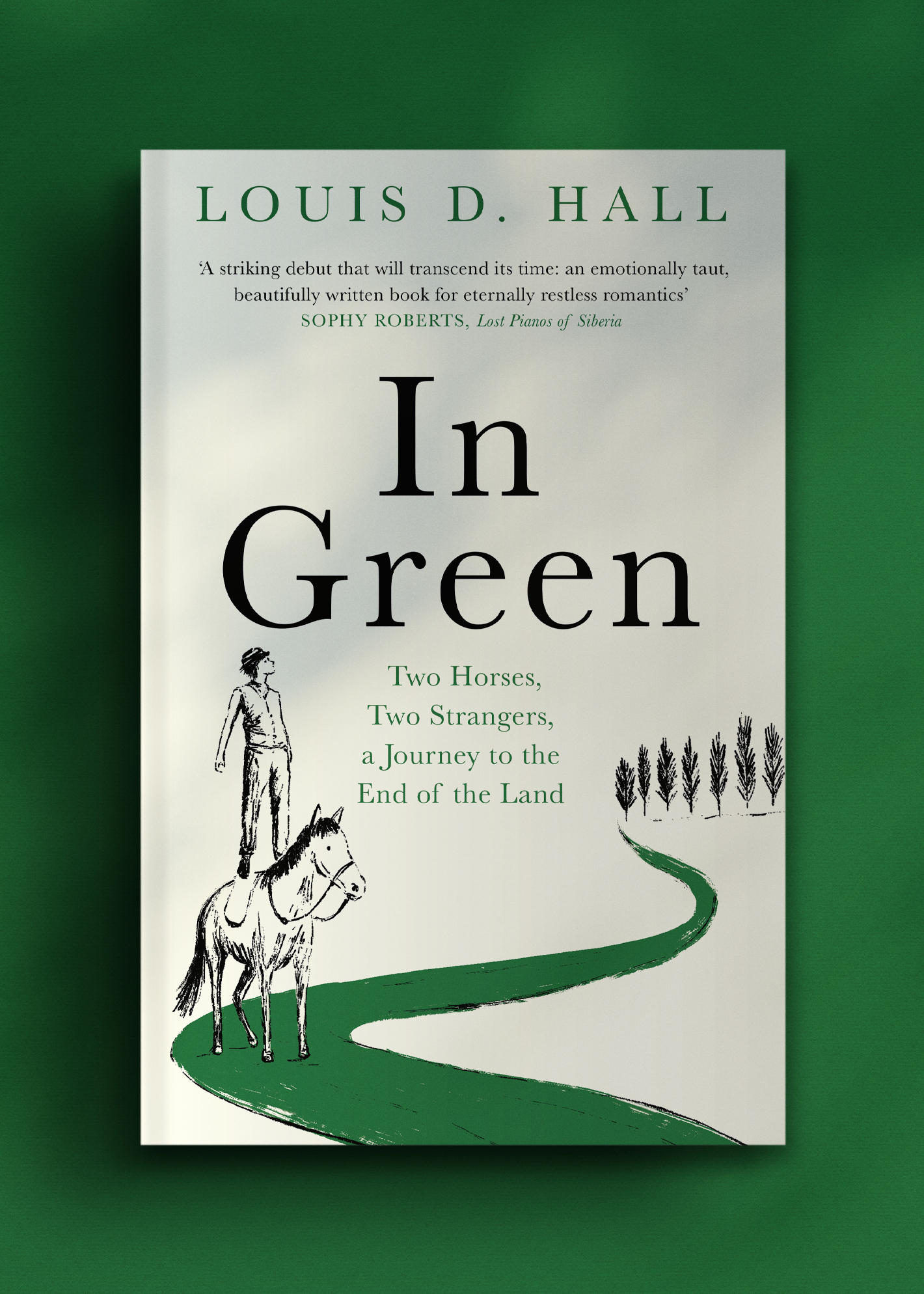

In Green: Two Horses, Two Strangers, a Journey to the End of the Land

Duckworth Books, 20 March, 2025

RRP: £18.99 | 304 pages | ISBN: 978-1914613838

An utterly enchanting debut – a new favourite book. I was riding side by side with the author, every step of the way” – Antonia Fraser

‘I need to ride now, to explore, to uncover more life; to reach strangers, to feel danger and to learn; to share this old, slow way, with man’s patient, most forgiving and most loyal friend – the horse.’

In his mid-twenties, restless in the routine of a city, Louis D. Hall found himself wondering how to create the life he wanted to lead. Inspired by Don Quixote, he decided to fulfil a childhood dream – to make an uncharted journey on horseback.

After finding his horse Sasha in Italy’s Apennine Mountains, the pair set off and headed west for Cape Finisterre, ‘the end of the land’, unprepared for most of the dangers – snow, storms, wolves – that faced them. He was even less prepared for the lessons that both Sasha and the young woman who joins them part way taught him about life's potential and its complexities.

A glorious piece of rich, romantic travel writing that takes the reader along old paths, into ancient villages, sharing rural homes and stables of farmers and shepherds in the Ligurian Alps, Pyrenees, Basque country and Galician coast, from a brilliant new talent.

“A classic adventure narrative in the vein of Patrick Leigh Fermor and Robert Louis Stevenson: this is a life-changing, continental trek on foot and on horseback that captures the clarity, freedom and desperate joys of long distance travel and the closeness and intimacy of the herd. Romantic in so many senses of the word – a love story, a wilderness quest, a kaleidoscope of European culture and language”

― Cal Flynn

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store