The Last French Emperor

Edward Shawcross on Napoleon III and the dynasty that wasn't

On 9 January 1873, in a quiet village in Kent, the former French emperor, Napoleon III, died. His funeral saw thousands of people descend on this quiet Kent village. British onlookers mingled with European aristocracy alongside French generals, admirals and politicians to watch the cortege of the last sovereign of France.

How a French emperor came to die in Camden Place, a British country house which is now a golf club, is an unlikely tale. But the story of how he became an emperor is even more remarkable.

Though he was born close to the imperial throne of France, much of his life was spent far from it. His uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte, was determined to found a dynasty, but had no children with his first wife, Josephine. She did, however, have a son and daughter from a previous marriage and the couple alighted on an innovative if unusual solution: her daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais, would marry Napoleon’s brother, Louis.

From a dynastic point of view this worked, producing two children that survived into adulthood: Napoléon-Louis and, in 1808, (the originally named) Louis-Napoléon, who would grow up to be Napoleon III. As a marriage, though, it was a disaster. Sophisticated and intelligent, Hortense despised the temperamental Louis. He swung between intense feelings of love, hatred and paranoid jealously, questioning whether he was the father of the younger son.

With Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, Bonaparte was no longer a surname that opened doors. Moreover, Louis ended the marriage, taking his preferred elder son to live with him in Italy, while Louis-Napoléon grew up in exile with his mother. Hortense found refuge in Switzerland. She purchased a chateau, turning it into a museum to Bonapartism and inculcating a religious reverence for the former emperor in her son.

Louis-Napoléon was not a driven student, except when it came to the cult of his uncle, but he was intelligent and did well enough at school. Raised on tales of his family’s greatness, however, he yearned to escape the boredom of rural Switzerland.

His older brother, who had come of age in Italy, provided the excitement. Napoléon-Louis was swept up by the intoxicating romanticism of liberal Italian nationalism. He took his impressionable younger brother along to smoked-filled taverns where secret societies of revolutionaries plotted to overthrow the old order – namely Austrian rule in the north and reactionary Papal control over Rome.

In 1831, the two brothers joined a revolt that aimed to unify Italy. It was a disaster. The forces of order routed the ramshackle rebellion and the two brothers went on the run. Napoléon-Louis fell ill in northern Italy, dying of measles in his younger brother’s arms.

Louis-Napoléon also fell ill, but his mother came to the rescue. Journeying overland, she found a villa for her ailing son to convalesce in; however, to her horror, the very Austrian troops that were hunting down insurgents requisitioned the building as their headquarters.

For days, Hortense stifled the coughs of her son lest they were overheard. When he was finally well enough to travel, Louis-Napoléon disguised himself as one of his mother’s servants while she travelled under a false British passport in the name of Mrs Hamilton as they made their escape.

Obsessed with his uncle’s legacy, Louis-Napoléon was far from being heir to it. That was the Duke de Reichstadt, Napoleon Bonaparte’s son through his second marriage to an Austrian archduchess. After defeat at Waterloo, Bonaparte abdicated in favour of his four-year-old son, Napoleon II. Few others recognised him as such, but he was the Bonapartist successor until he died of tuberculosis in 1832, aged 21.

From that moment, Louis-Napoléon became convinced that it was his destiny to restore his uncle’s empire. Apart from a small cadre of misfits, rejects and sycophants, most people laughed at this ambition, but Louis-Napoléon was unwavering. As the political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville noted, “I doubt whether [the Bourbon king] Charles X was ever more infatuated with his legitimism than [Louis-Napoléon] with his.”

Nonetheless, disappointed with the work of providence, Louis-Napoléon took matters in to his own hands and launched a coup d’état. The plan was to present himself before a loyal Bonapartist regiment at Strasbourg, which would march with him to Paris and proclaim him emperor.

Early in the morning on 29 October 1836, he approached the barracks. Urging him on, one of his supporters reassured him that all France was behind. This was true literally – Strasbourg is on the French-German border – but not figuratively. The regiment did not rally to him, let alone France, and Louis-Napoléon was arrested. The government of the day, more embarrassed than angry, simply insisted that the pretender go back into exile.

When he tried again in 1840, this time landing from the sea at Boulogne, the government was less forgiving. Failure is too grand a word for this farce, as once again a supposedly loyal regiment failed to rally. Seeing the futility of the situation, Louis-Napoléon tried to row back to the boat that had carried him from England, but capsized and had to be fished out from the waves by the soldiers who had declined to join his revolt. Soaking wet, he was arrested on the beach.

This time, Louis-Napoléon was locked up in the prison fortress of Ham in northern France. It was a fairly comfortable incarceration. He struck up a romance with a young laundress, offering her French grammar lessons, and she gave birth to two of his sons. Still, prison was no place for a man of destiny, and in 1846 he found another opportunity to practice his skill at disguise. The fortress was being repaired, and so Louis-Napoléon, dressed in the clothes of a workman, picked up a wooden plank, put it over his shoulder and walked out of the front gate before fleeing to London. And there it would have ended had it not been for the providential moment Louis-Napoléon had been waiting for: the 1848 revolution. In the face of popular protests in Paris, the French king abdicated and a republic was set up; elections for its president were to be held in December.

The Second Empire of France

Despite no experience of democratic politics, and no political party, Louis-Napoléon announced to a cousin “I’m going to Paris. A republic has been proclaimed. I must be its master.” To which his cousin responded, “You are dreaming, as usual”.

Louis-Napoléon seemed ill-suited to the task. For his opponents, he was a scandalous, 40-year-old failed adventurer with an absurd military moustache, large nose, and pointed goatee. At 5 foot 4 inches he was short for the time, walked with a comic shuffling gait, and had a famously lustreless gaze. And he was an appalling public speaker who spoke with a Swiss-German accent.

Worse yet, he had an English mistress, Harriet Howard. She was a failed actress turned wealthy kept woman who became Louis-Napoléon’s lover, and financial backer – a combination which proved too much even for French politics. In short, this was not the man the political elite had hoped would lead France in a glorious new republican dawn.

But he was the man they got, winning the election with a landslide 74 percent of the vote. In no small part this was down to brand recognition. The name Bonaparte still resonated throughout France, and enough time had passed to forget the horrors of his uncle’s regime leaving only nostalgia for the glory. Bonapartism was vague enough to appeal across the political spectrum, and Louis-Napoléon was skilled at appearing as all things to all men – and it was only men who voted.

The political class were horrified. Alexis de Tocqueville compared him to a “dwarf” who “on the summit of a great wave is able to scale a high cliff which a giant placed on dry ground would not be able to climb”. Victor Hugo famously called him Napoléon le pétit. The monarchist politician and thinker, Charles de Rémusat, simply went with “idiot”.

But this “idiot” outwitted all his opponents. The constitution prohibited re-election and the prince-president, as he was known, artfully sowed a narrative of the people versus the elites, making the national parliament and other democratic institutions look like the creatures of wealthy, vested interests. Famously taciturn – he spoke five languages and it was said he could be silent in all of them – he nonetheless proved a skilled manipulator of people. He built up a powerbase. To those he trusted he was witty, generous and farsighted. He soon had a loyal cadre of supporters in the army, and was able to win over church leaders.

He even secured a majority in parliament to revise the constitution to allow re-election, although not the three-quarters required by law to change it.

With his legal path to power blocked, third time lucky, he launched a successful coup d’état on 2 December 1851 to retain power. There was street fighting in Paris, and more determined resistance outside the capital – both were brutally repressed. A year later he proclaimed himself Napoleon III, Emperor of the French.

Karl Marx provided the epitaph for this Second Empire: “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Initially, though, it did not seem so farcical. Napoleon III created what today would be called an illiberal democracy and centred the regime around himself as a populist leader embodying the national will.

He used plebiscites to demonstrate this, reserving the right to appeal directly to the French people. Never stupid enough to put a question to the French people he might lose, he legitimised his rule – in his own eyes – with two votes. The first asking the French people whether they approved his continuation in power; the second if the empire should be re-established – over 7 million Frenchmen voted yes.

That the right could appeal to a mass electorate was a transformational moment in politics. Louis-Napoléon can claim to be the world’s first modern populist politician. As he supposedly said, “do not fear the people, they are more conservative than you”.

The first decade of his rule seemed a tremendous success. With the economy booming and railways expanding, Napoleon III’s regime transformed Paris. The project, overseen by the all-powerful prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, was enormously controversial and corrupt, but the wide boulevards, monumental stations and beautiful parks of today are a legacy of the Second Empire.

Politically, Bonapartism drew on many different traditions. The emperor hoped to create a government that was liberal and conservative, reconcile class conflict, and put economic and technological progress at the heart of government. Whilst in prison, he had written a utopian pamphlet called ‘The Extinction of Pauperism’. Critics quipped that he had only meant his own, but his well-intentioned if impractical principles never left him. In 1868, he sketched out a plan for a novel which gives an idea of his plans. In the book a Frenchman who had lived in the United States for decades returns home. He is astounded by the material progress, the railways, telegraphs, wide, clean streets of Paris and the people going to the Hotel de Ville to vote, rather than riot.

How much he achieved of this is an open question; however, as 1870 began his rule seemed stronger than ever. Unlike most dictators, he had liberalised over time. From 1860 onwards there was a greater role for parliament, a freer press and the right the strike, among other reforms. In January 1870, he put another plebiscite to the people: do you agree with these constitutional changes? Again, over 7 million voted yes, 82.7 percent of the turnout.

Of course, there were riots, protests and an increasingly popular republican opposition, yet few observers predicted the end of his reign. The British constitutional theorist Walter Bagehot described France as the “best finished democracy which the world has ever seen”.

It was not Napoleon III’s domestic policy, then, that led to his downfall, but his conduct of foreign affairs. In this he was (un)ably abetted by his wife, Eugénie. Harriet Howard had been handsomely, if reluctantly, paid off. Louis-Napoléon could just about keep an English courtesan as unofficial first lady of France, but, as the daughter of a Brighton boot-maker, she could never be empress. After a string of royal matches prove impossible – the reigning families of Europe unwilling to betroth even unloved daughters to an arriviste Bonaparte – Louis Napoléon decided on a forceful, headstrong Spanish aristocrat, Eugénie de Montijo, marrying her in 1853. His advisers hated the match; he insisted it was for love.

Love or not, he didn’t remain faithful for long. Eugénie produced an heir in 1856, but a difficult childbirth meant she did not want more children. Her husband had a string of scandalous mistresses, including the outrageously glamorous Virginia Oldoïni Rapallini, Countess of Castiglione; (allegedly) the wife of his cousin and foreign minister, Marie-Anne Walewska; and, most outré of all, Marguerite Bellanger, former chambermaid, one-time actor and circus performer (the emperor’s opponents used more derogatory terms for her profession).

One woman who the emperor had flirted with described a later rendezvous she had arranged with him in the early hours of the morning. The emperor appeared in her bedroom at 1.30am in billowing purple silk pyjamas. He clumsily approached her bed, stumbling over furniture in the near darkness. By the 2am the emperor had gone. “It had only taken half an hour to make me an empress,” she noted.

His enemies depicted him as a depraved and debauched lothario, picking out women from lines who he would later sleep with. In fact, there was little especially unusual about his behaviour for the mid-nineteenth century: in the years 1848-51, Louis-Napoléon’s most famous enemy – and France’s most celebrated poet – Victor Hugo, had slept with more women than he wrote poems.

The rumour was that as a form of penance for his affairs, Louis-Napoléon allowed Eugénie a free hand in politics, especially foreign policy. Certainly her influence was unhelpful, although the emperor was more than capable of blundering on his own. As his foreign minister said, “The emperor has immense desires and limited abilities”.

At first, Louis-Napoléon appeared to have restored France to glory with the Crimean War (1853-6). Although it was haphazardly entered into and incompetently prosecuted, it resulted in victory and the peace treaty was signed in Paris, giving credence to claim that the capital was the centre of the world. It was also fought in alliance with Britain, ending France’s isolation after the defeat of his uncle in 1815.

That was about as good as it got. Louis-Napoléon’s foreign policy was contradictory: he supported Italian unification but maintained a French garrison in Rome which prevented the city becoming the capital of the newly formed nation-state; he wanted international congresses to settle the great questions peaceably, but revelled in secret diplomacy that often resulted in war; and he wanted to end France’s isolation, but by the late 1860s was so distrusted that he ended up alone.

Someone who paid the price of these failings was Ferdinand Maximilian von Habsburg-Lothringen, younger brother of the Austrian emperor.

In 1862, Napoleon III had launched an outrageous attempt at regime change, trying to overthrow the legitimate president of the Mexican republic and replace him with French-backed monarchy headed by Maximilian. Faced with determined Mexican resistance, US pressure and Maximilian’s penchant for pomp and butterflies over practical administration, Napoleon III withdrew French troops, leaving his former friend to his fate.

Facing a court martial in Mexico, after the collapse of his regime, Maximilian vowed that if he ever got back to Europe he would enrol in the Prussian army to fight against the French. He never did return. The French artist Édouard Manet immortalised his death in a painting with a message that Maximilian would have welcomed: the member of the firing squad preparing the coup de grâce shares the features of Napoleon III. The implication was clear: the French emperor had blood on his hands.

Perhaps it would have been some comfort to Maximilian then that in 1870 the Franco-Prussian war that he had hoped for broke out. Determined to unite Germany, Otto von Bismarck manoeuvred Napoleon III into a war he knew the French were ill prepared to fight. Trapped by his sense of Bonaparte destiny – and the insistence of his wife – the French emperor took personal command of the army. He was in no state to do so. Seriously ill with numerous complaints including bladder stones that meant he was in excruciating agony, Napoleon III was in too much pain to ride out from Paris with his troops, instead taking the train. Unlike his uncle, the emperor was no military genius and he soon handed over command to his generals, but Eugénie, who was acting as regent, demanded he stay at the front rather than return to Paris.

The French generals were only a little more competent, and a series of defeats followed. Soon a French army was cut off and another sent to relieve it, with Napoleon III in its ranks, was surrounded at Sedan, a small town near the German border. As one French general put it with Gallic bluntness, the emperor’s army was “in a chamber pot, about to be shat upon.”

In the middle of this chamber pot was Napoleon III’s headquarters. At 5am on 1 September 1870 he heard the thunder of artillery. Battle had begun. Determined to show himself to his men, the emperor mounted his horse with towels stuffed into his underwear to ease the discomfort, and soak up the blood.

With cool resignation, and chain smoking as always, Napoleon III advanced into a blizzard of bullets and shells towards an exposed artillery battery. The weather was splendid, and below the emperor could see the massed ranks of enemy lines. The French army was in disarray, and its soldiers fleeing for the town.

A few paces away, a shell exploded in front of the emperor, covering him in a shower of dirt. Another blast knocked several aides’ horses to the ground, wounding the riders and leaving two of the mounts dead in the street. Despite the danger, the emperor twice had to go on foot, so painful was it for him to remain in the saddle. Finding it futile to go further, the emperor made his way through what remained of his terrified army back to his headquarters.

Horrified by the carnage, and convinced defeat was only a matter of time, the emperor ordered a white flag to be hoisted from the old citadel that dominated the town. He wrote to the King of Prussia, “not having been able to die amongst my troops, it only remains for me to surrender my sword into your hands”. The French capitulated unconditionally, and some 80,000 men were taken as prisoners of war, including the former emperor, who remained a captive for some months in Germany. Condemned as cowardice and incompetence at the time, it was a heroic decision against the advice of his generals that saved many lives. If he had shown such resolve two months earlier he might have avoided a war he knew the French army was not ready to fight.

Exile in England

In the capital, Eugénie was determined that her husband’s regime continue, but the people of Paris had other ideas: a republic was declared and a mob stormed the Tuileries. Eugénie narrowly escaped before fleeing incognito to England with the aid of an American dentist. She set up home at Camden Place, in Kent, with her son. In 1871, Louis-Napoléon, as he now was again, joined his family.

Even here, he didn’t stop plotting, dreaming of returning to France and power; but his health was failing. His doctors recommended an operation to remove his bladder stones at the beginning of 1873. The first two attempts were unsuccessful and a third was planned. In great pain, heavily medicated and often delirious, in a moment of semi-lucidity he turned to his doctor of some 40 years and asked, “were you at Sedan?” The doctor said yes. “We weren’t cowards there, were we?”

He never underwent the third operation. His condition rapidly deteriorated on the morning of 9 January and he passed away at 10.45am.

In France he wasn’t much mourned. Louis-Napoléon and his regime were convenient scapegoats for the humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War. Then French historians who reified the republican tradition buried the Second Empire as a bizarre aberration, while others rehashed the invective of some of the finest minds of the nineteenth century – Tocqueville, Hugo, Marx – as their own conclusions.

It is perhaps fitting then that today his remains are at St Michael's Abbey, Farnborough. An anglophile who spent three periods of exile in Britain, in many ways Louis-Napoleon was more readily accepted amongst the British than the French – he counted a prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, and a foreign secretary, James Howard Harris, 3rd Earl of Malmesbury, as friends. Queen Victoria and William Gladstone came to visit him in Chislehurst; Harriet Howard, some would argue, was his true love.

On the morning of 9 January, his son reached his father’s bedside too late. He had been summoned from Woolwich where he was a cadet in the British army. He too dreamed of power in France, but first wanted to win military honours. Insisting on serving in the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879, the great nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte and the son of the last emperor of the French died in British army uniform in modern-day South Africa. Eugénie survived them both, building the mausoleum for her husband and son where their remains still lie. She is buried with them too, dying in 1920, a relic of a long-forgotten empire •

This feature was originally published January 26, 2023.

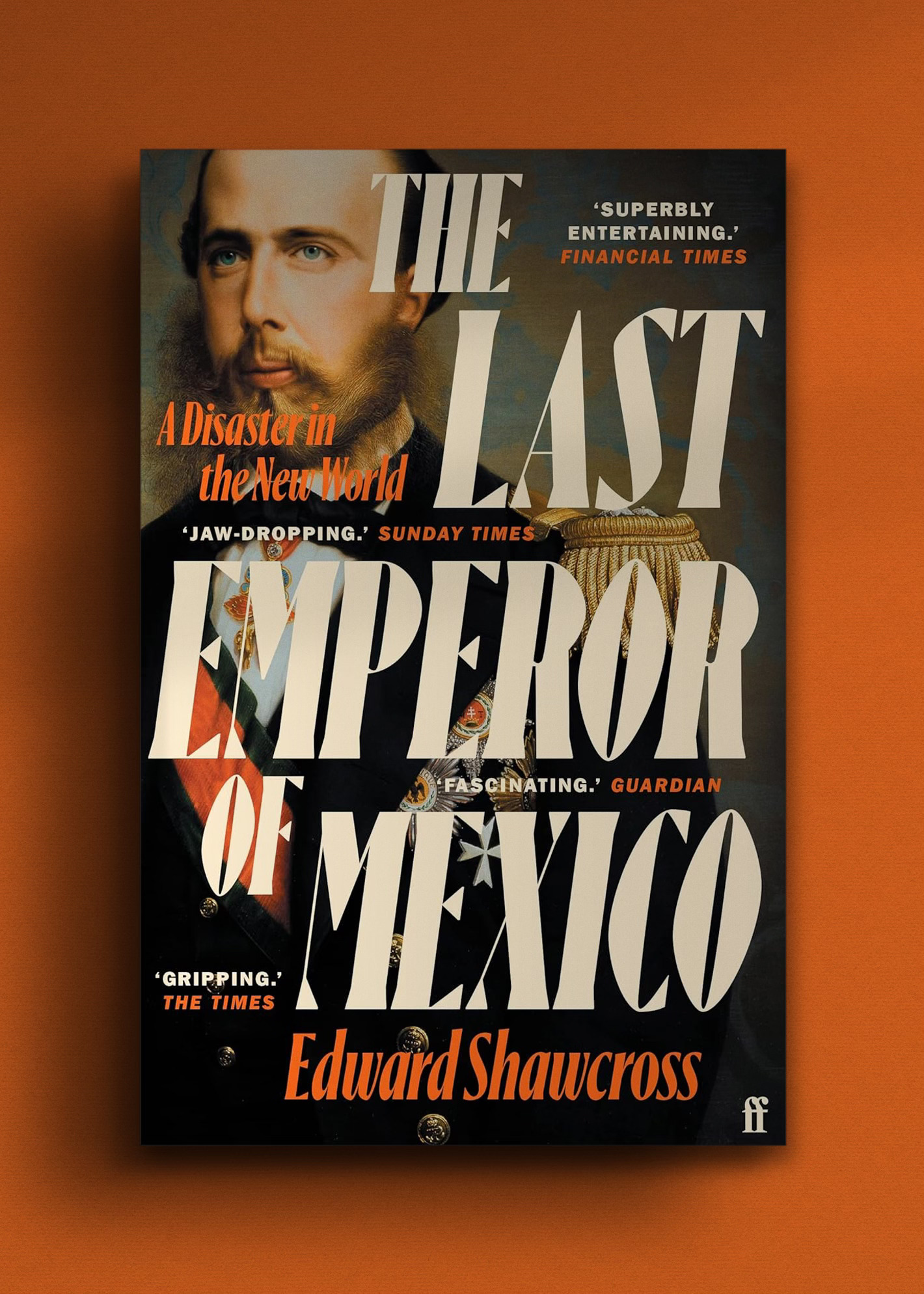

The Last Emperor of Mexico: A Disaster in the New World

Faber, 5 January, 2023

RRP: £12.99 | ISBN: 978-0571360581

“Superbly entertaining”– The Financial Times

In 1864, a young Austrian archduke by the name of Maximilian crossed the Atlantic to assume a faraway throne.

He had been lured into the voyage by a duplicitous Napoleon III. Keen to spread his own interests abroad, the French emperor had promised Maximilian a hero's welcome. Instead, he walked into a bloody guerrilla war. With a head full of impractical ideals - and a penchant for pomp and butterflies - the new 'emperor' was singularly ill-equipped for what lay in store.

This is the vivid history of this barely known, barely believable episode - a bloody tragedy of operatic proportions, the effects of which would be felt into the twentieth century and beyond.

“Jaw dropping” – The Sunday Times

More

Travels Through Time Podcast: The Last Emperor of Mexico with Edward Shawcross (1867)

In this episode of the hit podcast Travels Through Time, Edward Shawcross takes us back to meet Maximilian, the Last Emperor of Mexico in the nineteenth century to examine an event that Karl Marx called ‘One of the most monstrous enterprises in the annals of international history.’

With thanks to Arabella Watkiss. Author Photograph © Edward Stone.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store