The Maginot Line

Kevin Passmore examines one of the great defensive fortifications in modern history

Today the Maginot Line is remembered as an expensive failure. Built in the 1930s to safeguard France from German expansion, it was rendered useless in the space of just a few weeks as Hitler's forces blitzed their way to the north of it.

Kevin Passmore is the author of a new study, The Maginot Line, that examines its singular history. This excerpt from the book frames the reality for soldiers serving in one of its forts during the Nazi invasion of May 1940.

With an introduction by Kevin Passmore

The Maginot Line was one of the greatest engineering feats of its age, comparable in ambition, scope and social and political impact to contemporaneous megaprojects such as the Hoover Dam, the Moscow Metro and the German Autobahn.

The technical military aspects of the fortifications have been extensively researched, and some individual huge underground forts have been restored as tourist attractions and sites of commemoration and reconciliation. Yet nine decades later, the Maginot Line is a by-word for expensive-yet-useless defence against obvious danger. It figures in histories of the 1940 campaign as the antithesis of the German Blitzkrieg and as an afterword in a story that ended at Dunkirk – despite the fortifications becoming the site of the second greatest encirclement battle, after Kyiv in 1941, of the Second World War.

The Maginot Line: A New History casts some new light on the part played by the fortifications in the 1940 debacle without putting them on trial. It suggests that the fatal advance of Allied armies into Belgium, was not a product of what one historian calls a ‘Maginot mentality’, but the result of long-running conflict about doctrine and strategy – the Belgian operation owed much to a rejection of defensiveness, but was hamstrung by the weight of the Maginot Line in French military structures.

The primary purpose of the book, however, is to bring into view worthwhile stories that at most were tangentially relevant to the defeat in Belgium, if at all: the lives of the millions of labourers, often foreign, who built it, of the officers who regarded fortification service as second rank, of conscripts who endeavoured to evade harsh discipline, and of the mostly German-speaking population of Alsace-Lorraine where the fortifications were mostly built.

– Kevin Passmore

For references please consult the finished book.

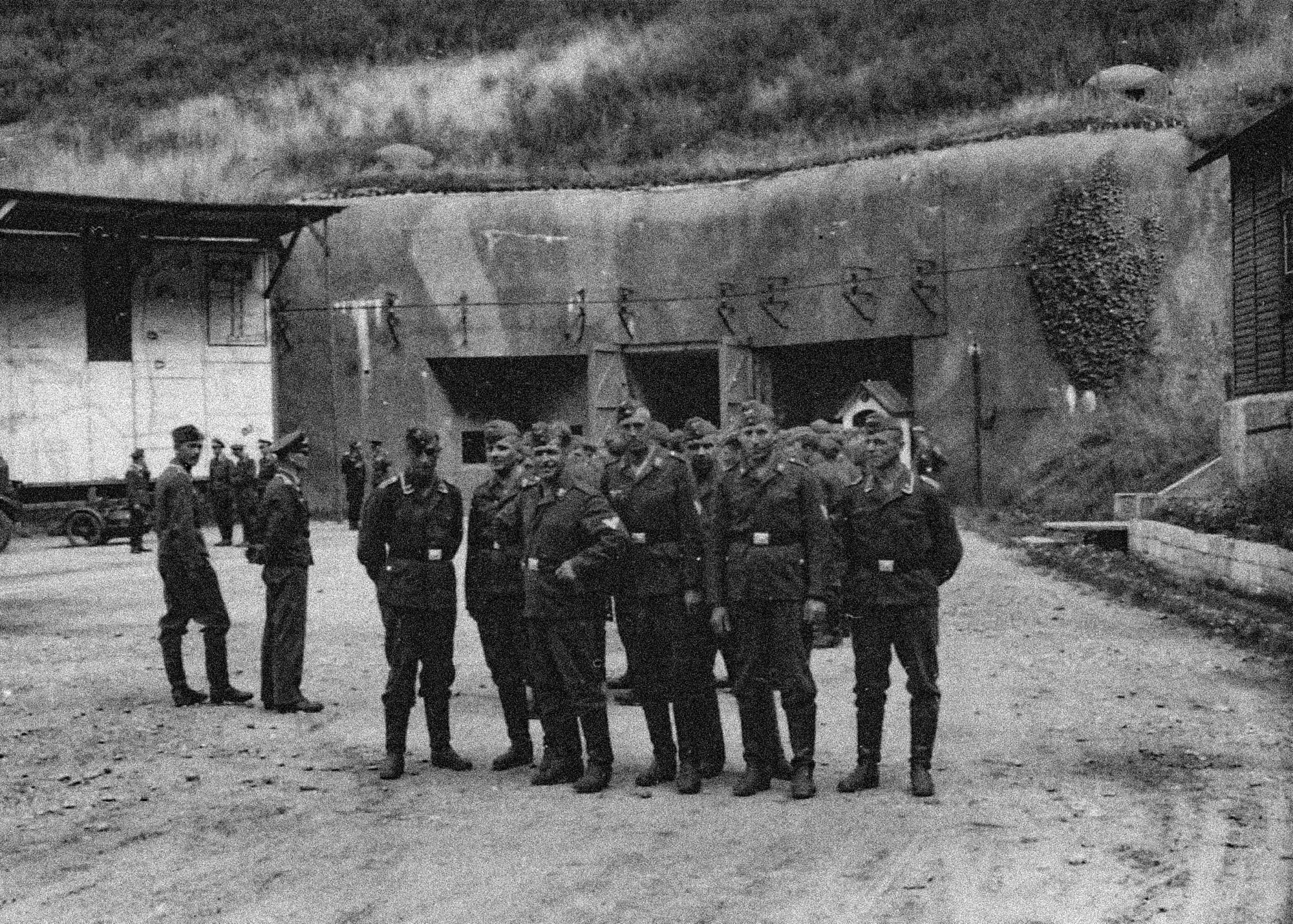

At dawn on 10 May 1940, Adjutant-chef Robert Lavergne, commander of the enormous Hackenberg fort’s Bloc 24, saw some five hundred aircraft flying into the interior. Later, he heard the sound of combat at the Maginot Line advance posts a few kilometres forward on the Franco-German border and of growling motors in the distance northwest towards Luxembourg. There, unknown to him, the flank guard of a huge Panzer force was pushing back French cavalry.

Lavergne, who had recently observed the combat systems of the aircraft-carrier Béarn, initiated the well-honed alert procedure. Observation cloches were manned, airlocks closed, gas alarms and turrets tested and light machine guns set up to defend underground communication galleries against infiltrators. By the 13th, the sector had quietened. Over the following weeks, the men had little to do besides test their weapons and await the electric trains bringing their rations – doubtless cold.

Life underground was challenging. A few months previously, parliamentary inspectors had found a well-organised crew with good morale ‘in this artificial atmosphere, difficult despite all the improvements’. They urged the purchase of ozonisers to neutralise ‘smells of all origins’ – they meant the kitchens and latrines.2 Over the eight months of the phoney war, damp, cold and artificial light produced a mental condition that the men labelled ‘bétonite’ – ‘concretitis’.

Hackenberg was the largest artillery fort, gros ouvrage, on the Maginot Line. Sited between the Moselle and Nied river valleys, it covered the most direct route from Germany to Paris. Laws of 14 January 1930 and 6 July 1934 funded nineteen such forts plus thirty-two infantry forts, petits ouvrages, and numerous interval casemates and shelters. They defended the border from Longuyon opposite Luxembourg to the Rhine at Lauterbourg.

The Rhine itself was covered by machine-gun casemates. The 1930 law also funded forts in the mountain passes and coastal plain on the Italian border, while the 1934 programme fortified a few key points in the north.

Individual forts such as Hackenberg were just one part of a huge military complex, consisting of special barracks for troops, garden cities for officers, military roads, narrow-gauge railways, electrical and telephone cables, command posts, planned flooding, thousands of miles of barbed wire and antitank rails and supply chains reaching across the French empire and the world.

During the war, nearly half of France’s two million front-line soldiers served on the Maginot Line at any given time and all the best divisions served tours there.

Hackenberg alone cost over 170 million francs to build – 135 million euros in 2024 prices – not including armament. Unusually, it consisted of two half-forts joined by an escarpment. In other respects, Hackenberg differed from other gros ouvrages only in the size of its crew – around one thousand men – and in the number of its individual fighting blocs, of which there were seventeen.

They were numbered up to twenty-four, however, for seven blocs never got beyond the drawing board. Four blocs were armed with rapid-fire 75mm guns with a range of up to twelve kilometres; two more housed 135mm indirect-fire howitzers. The other blocs were armed with combinations of antitank guns, mortars and light machine guns in cloches, machine guns in turrets and artillery casemates firing to the flanks.

Men and supplies all entered the Hackenberg through the misleadingly named munitions entrance, for its personnel entrance was actually an emergency entrance. Narrow-gauge railways led directly from a valley, through the munitions entrance down a slope under the hill, ninety-six metres underground at the deepest point.

Near the entrance were an infirmary, power plant, magazines, kitchens, officers’ mess and sleeping quarters. The main gallery then forked towards the two half-forts and then to the base of each combat bloc, several hundred metres forward. Shafts with elevators and steps led up to the turrets and casemates of the combat blocs at the surface.

Like almost all Maginot Line forts and Rhine casemates, Hackenberg was positioned in Alsace-Lorraine, which had returned to France in 1918 after forty-seven years of annexation to Germany. The local inhabitants were overwhelmingly first-language speakers of various German dialects and had multiple linguistic, economic and cultural ties to those across the border. Many of the soldiers serving in specially trained fortress artillery and infantry regiments were recruited from this population.

On 10 May 1940, further north on the Belgian border, the 106 soldiers manning petit ouvrage La Ferté, the last fort on the Maginot Line, also heard guns and aircraft. The alert shattered their dreams of relief from the crushing boredom of their ‘troglodyte life’ below ground, as one soldier put it.

The next day, the authorities ordered the inhabitants of neighbouring villages to evacuate. The sad spectacle prompted thirty-three-year-old Lieutenant Maurice Bourguignon, La Ferté’s commander, to remind his wife that as natives of the region, they too had fled the Germans in 1914. One soldier, who had seen his own family pass by, persuaded the military postmaster – a mobilised priest – to escort him to his farm in nearby Auflance, from where he returned with a shoulder of ham.

La Ferté was sited between the villages of Villy and La Ferté-sur-Chiers on a hill dominating the River Chiers, a tributary of the Meuse, the military importance of which all aspirant officers learned in their topography lessons.

Verdun, the scene of the battle of the Great War, was fifty kilometres upstream on the Meuse. La Ferté was part of fortified sector Montmédy (SF-Montmédy), an extension to the Maginot Line funded by the 1934 fortification law. These ‘new fronts’ were less powerful than the old, and La Ferté was their weakest link, armed only with antitank and machine guns. Its galleries were narrow and its rooms were too cramped for the crew.

On 12 May, Bourguignon, ‘courteous as ever’, allowed a local priest to say mass in one of the fort’s fighting blocks, for open-air services were now too dangerous. The priest reminded the congregation of its duty to defend the Ardennes people’s lives and property and asked them whether they were ‘ready in this just war that is now beginning to meet God’.

The next day, gunfire was audible towards Sedan, thirty minutes northwest. That was puzzling. The high command did not consider the area to be vulnerable, for it was covered by thick forest and the River Meuse. Its fortifications were intended merely to delay the enemy long enough to bring up reinforcements. Bourguignon told the priest not to return because the Germans were coming. The young lieutenant did not know that French plans were already unravelling. Arguably, within another day, the Battle of France was lost.

On 10 May, German forces, for whom the high command had ordered 35 million methamphetamine pills, had crossed the Luxembourg, Belgian and Dutch frontiers. Commander-in-Chief General Maurice Gamelin sent the best allied forces to meet what he thought was the main enemy effort in central Belgium and the Netherlands – the Dyle–Breda operation.

As Dutch resistance faded, the Germans broke the Belgian centre on the first day and quickly advanced towards the Allies. Although the Allies held the Panzers on the Belgian Plains, it counted for little, for they had entered a trap.

The main German thrust came further south through the Ardennes Forest. On 13 May, infantry crossed the Meuse at three points – Dinant in Belgium and Monthermé and Sedan in France. Panzer divisions then headed west and northwest to the Channel, thus encircling Allied forces in Belgium.

Prime Minister Paul Reynaud’s replacement of Gamelin with General Maxime Weygand (Gamelin’s predecessor as head of the army) did not change Allied fortunes. The armies trapped in Belgium fell back to Dunkirk, from where 338,000 troops were evacuated.

The Battle of Dunkirk over, the Germans assaulted French lines on the Rivers Somme and Aisne. They quickly broke through and fanned out over the country.

Now the Maginot Line too was encircled. On 10 June, Italy declared war on France. A week later, Marshal Philippe Pétain, hero of the Great War, formed a new government and sued for peace •

This excerpt was originally published September 8, 2025.

The Maginot Line: A New History

Yale, 28 August, 2025

RRP: £30 | ISBN: 978-0300277043

An authoritative and original history of the Maginot Line that reshapes our understanding of interwar France and the events of 1940.

The Maginot Line was a marvel of 1930s engineering. The huge forts, up to eighty meters underground, contained hospitals, modern kitchens, telephone exchanges, and even electric trains. Kilometres of underground galleries led to casements hidden in the terrain, and turrets that rose from the ground to fire upon the enemy. The fortifications were invulnerable to the heaviest artillery and to chemical warfare.

Despite this extensive preparation, France fell to Germany in a little under six weeks. Eight decades on, the Maginot Line is still remembered as an expensively misguided response to obvious danger.

In this groundbreaking account, Kevin Passmore reevaluates the Maginot Line. He traces the controversies surrounding construction, the lives of the men who manned the forts, the impact on German-speaking inhabitants of the frontier, and the fight against espionage from within. Far from a backward step, the Maginot Line was an ambitious project of modernisation―one that was let down by strategic error and growing dissatisfaction with fortification.

“By treating the Maginot Line as a subject for proper historical study rather than as a courtroom for trying the case of French 'decadence, ' Passmore shows its actual importance. This book is a superb blend of military, institutional, political, cultural, and social history”

— Leonard V. Smith, author of French Colonialism from the Ancien Régime to the Present

With thanks to Katherine Powell.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store