The Medieval Art of Graham Turner

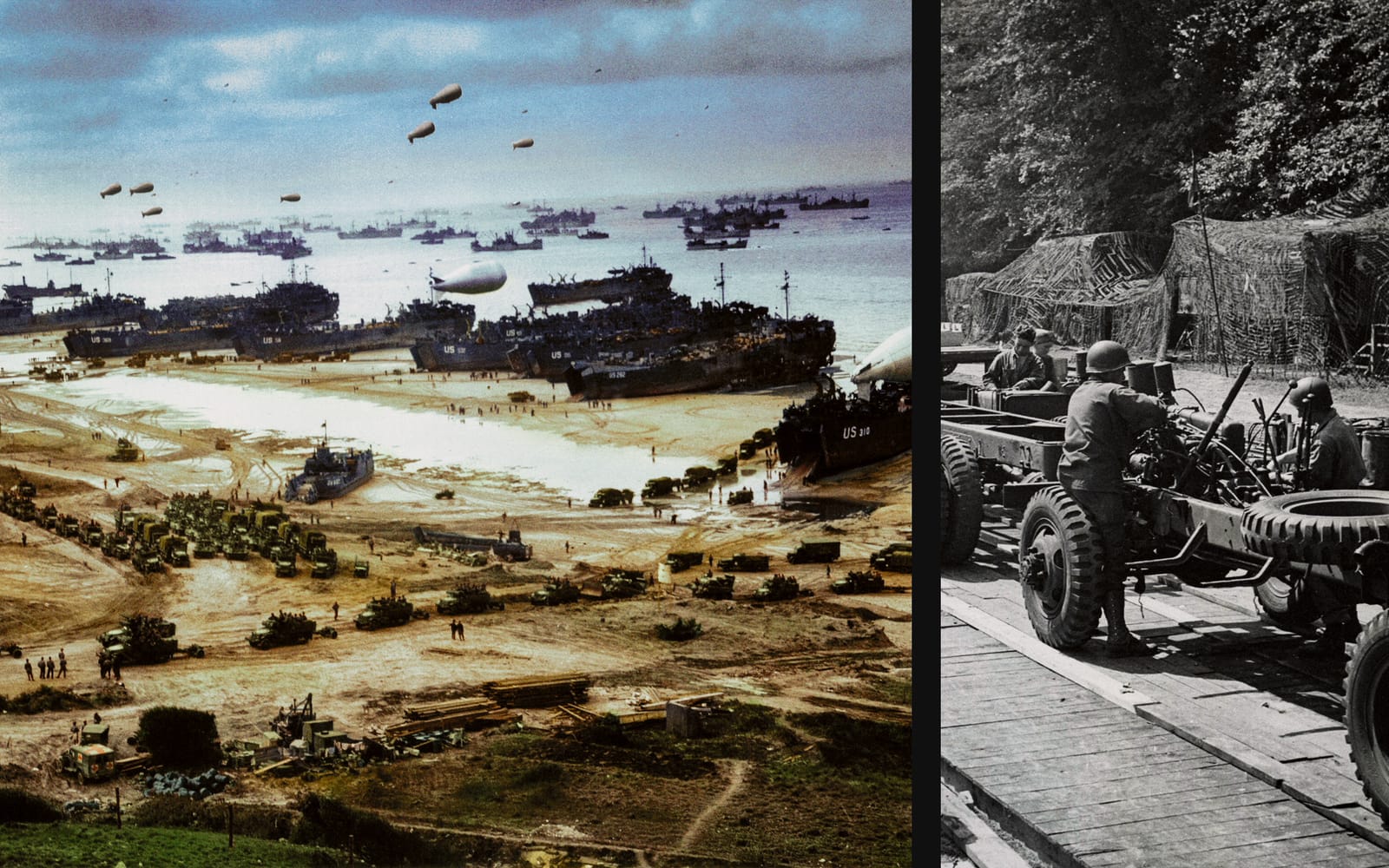

The artist Graham Turner casts an eye back to 1471 and one of the decisive moments of the Wars of the Roses: The Battle of Barnet

The artist Graham Turner traces his obsession with the Wars of the Roses back to 22 August 1995 when his first depiction of the Battle of Bosworth was unveiled at the battlefield's visitor centre.

Over the decades that have followed this occasion, Turner's work on the period has continued and deepened. 'History', he writes in the introduction to his new illustrated book on the conflict, 'becomes much more vivid and exciting when it involves times of trouble, plots, rebellion and war.'

All of these characteristics certainly belong to the Wars of the Roses. The term is a collective one for a grand series of dynastic conflicts that gripped England during the fifteenth century. The protagonists were broadly divided into the 'Yorkists' and 'Lancastrians' and the prize they sought was the English throne.

Words and Paintings by Graham Turner

The following extract is taken from Turner's newly published book, The Wars of the Roses: The Medieval Art of Graham Turner. Here you can see a series of Turner's highly-evocative and deeply-researched paintings that relate to one dramatic confrontation: the Battle of Barnet.

This battle took place in the fog (or 'greate myste') on Sunday 14 April 1471, a short distance to the north of London in Hertfordshire. The engagement was a ferocious one and it concluded with a decisive victory for the invading army of Edward IV, helping him to wrest the kingdom back from the Lancastrian King Henry VI

The Battle of Barnet is an event of great significance in English history. It involved many central figures of the time, particularly the mercurial Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, who led the Lancastrians and was killed in the engagement while trying to flee. Its immediate consequence was to usher in a final fourteen years of Yorkist rule before a new branch of Lancastrians, the Tudors, arrived.

The paintings shown below capture both the raw chaos and the formal elegance of a Medieval battle. They, along with the accompanying notes, also demonstrate Turner's commitment to extensive and diligent scholarly research.

When King Edward’s army reached Barnet, Warwick’s army was already in position, ‘undre an hedge-syde’. The king’s ‘afore-riders’ chased Warwick’s back to their positions and, as night fell, he formed his army up to face them.

It would transpire that he was much nearer Warwick’s lines than anyone realised, and not quite opposite ‘butt somewhate a-syden-hande’. Both miscalculations would have a considerable bearing on the outcome of the following day’s battle. While Warwick’s gunners fired throughout the night, the closeness of the two armies meant their shot passed harmlessly overhead, and Edward kept his soldiers ‘still, withowt any mannar langwage, or noyse,’ and ‘suffred no gonns to be shote on his syd’.

'‘And on Ester day in the mornynge, the xiiij. day of Apryl, ryght erly, eche of them came uppone othere; and ther was suche a grete myste, that nether of them myght see othere perfitely’'

– Warkworth’s Chronicle

A ‘greate myste’ greeted the tired soldiers as Easter Sunday dawned, with gun smoke from the night’s barrage hanging in the air to further hamper visibility. Despite that, Edward immediately ‘commytted his cawse and qwarell to Allmyghty God, avancyd bannars, dyd blowe up trumpets, and set upon them, firste with shotte,’ and then very soon ‘they joyned and came to hand-strokes’.

In the centre the fighting was fierce, but on Edward’s right, Gloucester’s division found itself with no opposition, the result of the previous night’s misalignment. As Gloucester swung his division round he found the enemy and attacked, engaging what was probably the flank of Warwick’s left, under the command of the Earl of Exeter.

Challenge in the Mist

Nineteen-year-old Richard, Duke of Gloucester, strains to see the enemy through the thick fog that envelops the battlefield at Barnet on 14 April 1471. He would later have several of his retainers remembered in prayers, ‘slayn in his service at the batalles of Bernett, Tukysbery or at any other feldes’.

Oil on canvas, 24” x 30” (61cm x 76cm), 2000.

‘for the Kynge… mannly, vigorowsly, and valiantly assayled them, in the midst and strongest of theyre battaile, where he, with great violence, bett and bare down afore hym all that stode in hys way’

– The Arrivall

On the other wing the opposite had happened, and here the earl of Oxford’s division outflanked and defeated the Yorkists of Lord Hastings, chasing them from the battlefield. It took some time for Oxford’s captains to regroup his men, some of whom were busy pillaging in Barnet, and return to the battlefield, but when they did it would have a decisive effect.

In the centre, apparently largely unaware of the ‘distrese’ on the flank ‘by cawse of [the] great myste that was, whiche wolde nat suffre no man to se but a litle from hym’, the fighting was intense. King Edward led from the front, where he ‘mannly, vigorowsly, and valliantly assayled them, in the mydst and strongest of theyre battaile, where he, with great violence, bett and bare down afore hym all that stode in hys way’.

The Battle of Barnet, 14 April 1471

Edward IV leads his army through the fog and into the thick of the action, his banners flying above him and Knights of the Body beside him. Opposing the king are soldiers wearing the red livery of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, Edward’s one-time great ally, and in the background can be made out the ‘Kingmaker’ himself, along with his brother, John Neville, Marquess Montagu.

Oil on canvas, 48” x 32” (122cm x 81cm), 2018.

As Oxford emerged from the mists to rejoin the battle, he should have found himself approaching the rear of the Yorkist lines. However, due to the misalignment, the battle lines had rotated and it was the flank of the division commanded by his ally, Montagu, that his men bore down upon.

Oxford’s men wore ‘ther lordes lyvery, bothe before and behynde, which was a sterre withe stremys, whiche [was] myche lyke Kynge Edwardes lyvery, the sunne with stremys’ [the sun in splendour], and in the thick fog the two badges were confused by Montagu’s soldiers, who thought they were being attacked by King Edward.

They fought back, and on realising that they were being attacked by their own side, Oxford’s men ‘cryed “treasoune! treasoune!” and fledde awaye from the felde’. With victory within his grasp, Warwick’s forces collapsed. Montagu was killed, and Warwick made his bid to escape. The horses had been sent to the rear and that’s where Warwick headed; ‘he lepte one horse-backe, and flede to a wode by the felde of Barnet’.

There, cornered, he was cut down and ‘despolede hyme nakede’.

Mistaken Identity

John Neville, Marquess Montagu, and men of his division spot the earl of Oxford’s troops returning through the fog to the battlefield. Mistaking their banners for those of their enemy King Edward would result in disaster as their army collapsed amidst cries of treason.

Gouache, 21.5” x 14.5” (55cm x 37cm), 2003.

The battle wasn’t particularly long, lasting either three hours or until 10am, according to two different sources. Alongside Montagu, the bodies of ‘many othar knyghts, squiers, noble men, and othar’ lay on the battlefield.

The chronicles often list the names of the notable casualties, but the majority of those killed are here simply acknowledged by the single word ‘othar’. Elsewhere these nameless casualties are referred to as ‘gode yemen, and many other meniall servaunts of the Kyngs’.

As with all the battles of the Wars of the Roses the numbers involved are extremely difficult to determine, with the accounts giving very different, often exaggerated, figures. At Barnet it has been suggested that King Edward fielded between 12,000 and 15,000 troops, Warwick slightly more, with 1,500 casualties being the more believable of the varying figures recorded by the chroniclers.

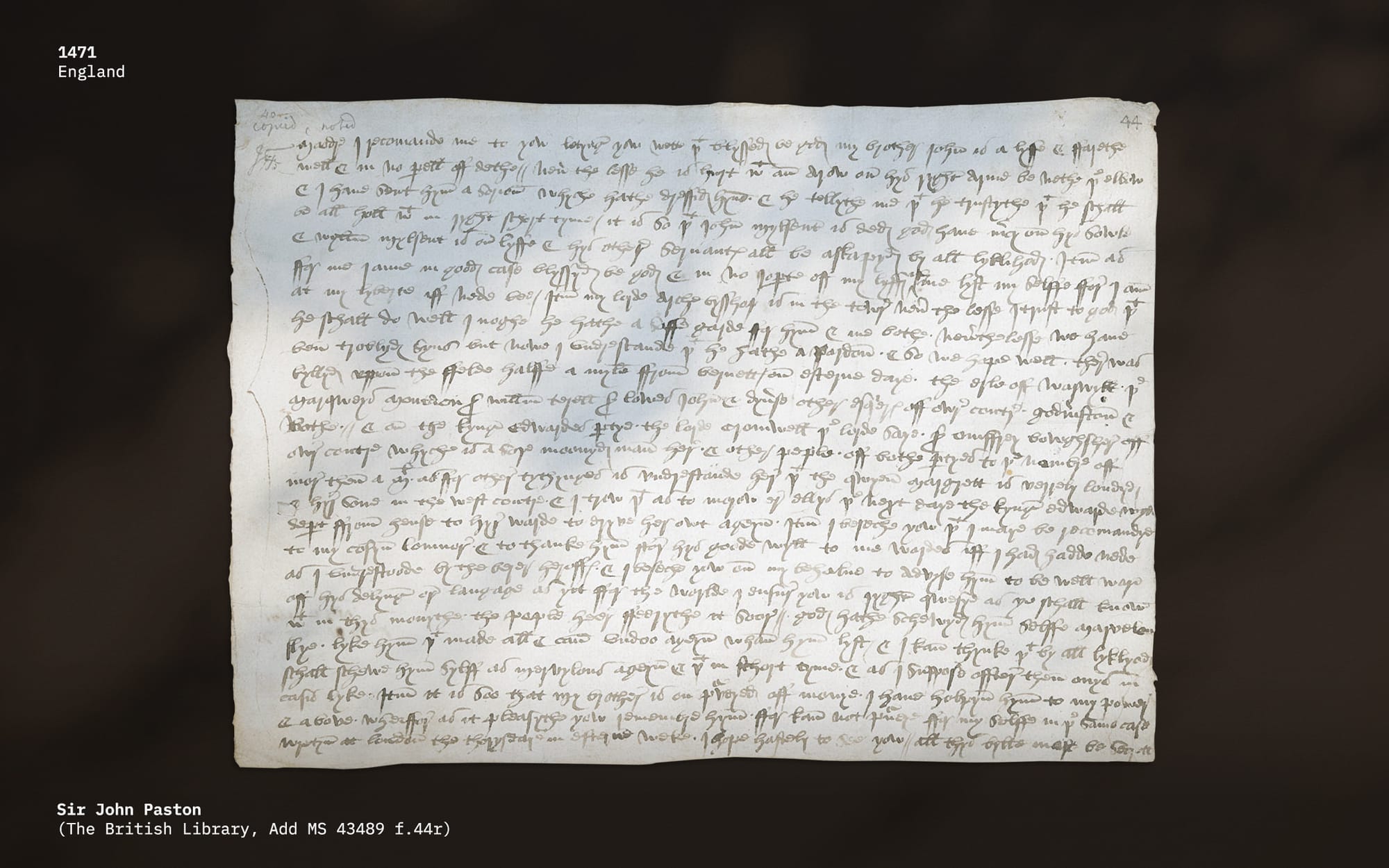

Sir John Paston, who was present, wrote ‘and other peple off bothe partyes to the nombre off mor then a m [thousand]’. On the Yorkist side the battle had claimed the lives of Sir Humphrey Bourchier, Lord Cromwell (son of the earl of Essex) and his cousin, another Sir Humphrey (son of Lord Berners), Sir William Fiennes, Lord Saye (whose father had been beheaded by the rebels in 1450 during Cade’s Rebellion), and Sir William Blount, son of Lord Mountjoy.

Edward IV at Barnet

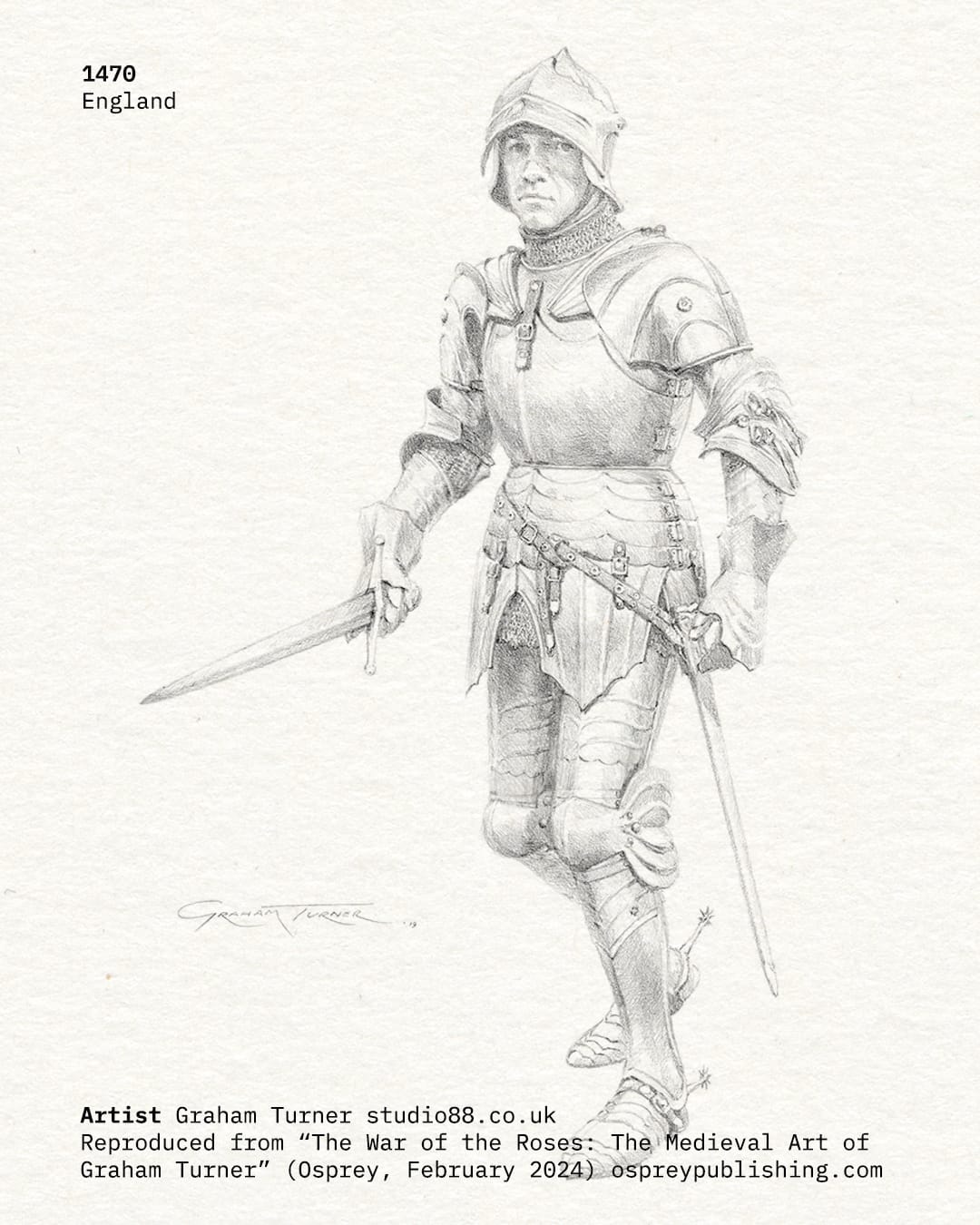

When Edward fled to the Continent in October 1470 he carried few possessions, so I resisted the temptation to equip him with an English armour and chose a style that could have been supplied in Flanders.

On his return to England in March 1471, he eased his progress by saying he had returned only to claim the duchy of York, so I have shown his helmet, an armet, decorated with a golden ball, pearls and feathers – as often depicted in contemporary manuscript illuminations – but then added the crown to symbolise his subsequent reclamation of the throne.

The crown is inspired by the surviving crown of Edward’s sister, Margaret, decorated with jewels set in enamelled white roses.

(Detail from the painting of the Battle of Barnet)

The duke of Gloucester’s first experience of battle had left him slightly wounded, as was Earl Rivers. Gloucester would later have several of his followers remembered in prayers ‘for the soules of Thomas Par, John Milewater, Christofre Wursley, Thomas Huddleston, John Harper and all other gentilmen and yomen servanders and lovers [friends and wellwishers] of the saide duke of Gloucetr, the wiche were slayn in his service at the battelles of Bernett, Tukysbery or at any other feldes’.

In the piles of dead and dying scattered across the battlefield, the duke of Exeter lay seriously wounded and ‘lafte for dead’. He was found by a servant late in the afternoon and treated by a doctor, before being smuggled into sanctuary at Westminster. Seized from there, he would spend the next four years in the Tower.

The earl of Oxford made good his escape, eventually reaching Scotland and from there getting to France, living to fight another day.

The victorious King Edward, after ‘he had a little refresshed hym and his hoste’, returned to London and rode straight to St Paul’s, where he was received by assorted ecclesiastical dignitaries, laid two badly torn banners at the altar ‘and rendered to almightie God, for his greate victory, moste hu[m]ble and hartie thankes’, before returning to his family at Westminster. It had been a busy day!

Henry VI, who had been taken to Barnet with the Yorkist army, was returned to the Tower, ‘ther to be kept’. A contemporary account of the returning army vividly illustrates the butchery of battle and the wounds sustained: ‘Those who went out with good horses and sound bodies brought home sorry nags and bandaged faces without noses etc. and wounded bodies, God have mercy on the miserable spectacle’.

The bodies of Warwick and Montagu were brought to St Paul’s, where they were laid on ‘the pavement, that every manne myghte see them’, to try to quell any ‘seditiows tales’ that they still lived. 31 They lay there for three or four days before they were taken for burial alongside their father, the earl of Salisbury, in the family tomb at Bisham Abbey.

After they had sought his backing in their dispute over Caister Castle, the two John Pastons had been called upon to fight for the earl of Oxford at Barnet.

They survived their undoubtedly traumatic experience, and on the Thursday after the battle Sir John wrote to their mother:

‘Moodre [mother], I recomande me to yow, letyng yow wette [know] that, blyssed be God, my brother John is a lyffe [alive] and farethe well, and in no perell off dethe. Never the lesse he is hurt with an arow on hys ryght arme, be nethe [beneath] the elbow; and I have sent hym a serjon [surgeon], whyche hathe dressid hym, and he tellythe me that he trustythe that he schall be all holl [whole, i.e. healed] with in ryght schort tyme.’

On 30 April, John III himself wrote to their mother, reassuring her that he was almost recovered:

‘I thank God I am hole of my syknesse, and trust to be clene hole of all my hurttys within a sevennyght at the ferthest’, but begging for funds because of the cost of his treatment; ‘I beseche you, and ye may spare eny money… and send me some in as hasty wyse as is possybyll’.

He signed the letter John of Gelston, his birthplace, and gave no address as he was yet to be pardoned; he would secure his pardon in February 1472, just after his brother, who wrote to their mother in January saying ‘I have my pardon… for comfort wheroffe I have been the marier thys Crystmesse’ •

This Viewfinder gallery was originally published March 19, 2024.

The Wars of the Roses: The Medieval Art of Graham Turner

Osprey, 15 February, 2024

RRP: £35 | 288 pages | ISBN: 978-1472847287

“If you only buy one book on the Wars of the Roses, make it this one, you won't be disappointed” – Battlefield

A highly illustrated history of the Wars of the Roses based on the medieval art of Graham Turner.

The period of civil strife in the second half of the 15th century now known as the Wars of the Roses was one of the most dramatic and tumultuous in English history.

Since first being inspired by a visit to Bosworth battlefield nearly 30 years ago, renowned historical artist Graham Turner has built a worldwide reputation for his depictions of this colourful and troubled era, his paintings and prints prized by historians and collectors for their attention to detail and dramatic and atmospheric compositions.

This new study contains a detailed history of the wars alongside a unique and comprehensive collection of over 120 of his paintings and drawings, many created especially for this book. It provides meticulously researched details of arms, armour, settings and countless other aspects of the period, while bringing to life the human stories behind the turbulent events.

“Beautifully illustrated and carefully researched. a unique and compelling book. A must have for anyone interested in this period”

― Anne Curry, Emeritus Professor of Medieval History and Chair of the Battlefields Trust

“This is one of the best books published on the Wars of the Roses in recent years. It will prove an invaluable resource for amateur and academic historians alike, as well as wargamers, reenactors and anyone with a passing interest in this fascinating period of English history”

― Toy Soldier Collector

All images are originally published in The Wars of the Roses: The Medieval Artwork of Graham Turner are used with permission by Osprey.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store