The Men Who Sold Honours

Stephen Bates looks back at a very British form of political corruption

In his new book, The Man Who Sold Honours, Stephen Bates charts the singular story of John Maundy Gregory.

In the early twentieth century Gregory was a confidant of kings, a suspect in a mysterious 'death riddle' and a political operative who made a fortune selling honours to wealthy individuals.

But while his story was unique, in many ways he only refined a form of political corruption that was generations old. Before Gregory many others had sold honours for money too, as Bates explains.

Rulers have rewarded followers, or at least bought their loyalty, for hundreds of years. It has not been unknown for kings to create titles specifically to raise money. James I did so in 1611 with the foundation of a new formulation of baronet, its status midway between a knighthood and a peerage, to help fund the cost of the plantation of Ulster.

The Stuarts, perennially short of money, created rafts of new peerages, openly sold at £10,000 a time. Then, in the 1780s, the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger created 141 new peers, with the consent of King George III, to create a Tory majority in the upper house.

But it is only in the last century or so that the practice of selling honours to raise cash for party political purposes or to bolster support in the House of Lords has come to be regarded as truly scandalous. Modern 'Cash for Honours' allegations make for sure-fire headlines.

The catalyst for this change is partly the Industrial Revolution, which saw for the first time political power and influence move from the landed aristocracy towards men whose wealth came from commerce and manufacturing.

As the franchise expanded, political parties needed to raise money to pay for campaigning: their candidates were not necessarily men of means, able to fund their own elections. Liberal and Tory organisers realised there were hitherto untapped resources from the business and banking classes, men who were willing to contribute money, to buy influence and to be rewarded with the prestige of a title.

Fundraising therefore became a major focus of party organisers. In 1880, for instance, the Liberals’ election fund stood at £30,000. Four Parliamentary reforms later, by 1906, the fund topped £120,000.

It was a fertile field, Sir Robert Peel, prime minister in the 1840s and a second baronet himself, was alive to the lure of an honour. 'I wonder people do not begin to feel the distinction of an unadorned name', he once told an aspirant loftily.

Peel grew fastidious about the sale of honours throughout his career a pratice that continued to gain momentum during the course of the nineteenth century. This was a time when men no longer needed landed estates to become peers. Sir Arthur Guiness became one in 1880. The poet Lord Tennyson followed in 1883 and Algernon Borthwick, owner of the Morning Post, became the first newspaper baron in 1895.

Queen Victoria generally acquiesced in this but she did object to ennobling Lionel de Rothschild in 1869.

Was it because he was Jewish? Apparently less because of that than because he was a banker: she apparently objected that he had made his money 'from a species of gambling far removed from the legitimate trading which she delights to honour.'

Lionel's son Nathan was eventually raised to the peerage 16 years later: the first Jew to sit in the upper chamber.

Even that pillar of rectitude William Gladstone lobbied the Queen for peerages to boost the Liberal presence in the Lords. About a quarter of all the letters he wrote to her during his lengthy periods as Prime Minister concerned the awarding of honours; and, much as she loathed him, she generally acquiesced.

By the early twentieth century the sale of honours was in full swing, though it was done rather secretively, almost shame-faced. It was privately normalised and publicly (and hypocritically) denied. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the future Liberal prime minister told the House of Commons in 1900:

'We in this country have happily been free for two or three generations from any imputation of mercenary or corrupt motives on the part of our public men, a thing that can be said of few other countries.'

– Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Both parties by then were employing so-called honours touts to raise funds by soliciting potential 'honorands'. Just how many of these touts there were is hard to gauge since politicians and party officials were also tapping-up likely clients, either by letter or in person.

What changed the scale of the practice was the ascent of David Lloyd George to power. He was the first prime minister who could be said to be from a truly working class background. He had grown up far from the centre of power in a small village in the north of Wales and he had very little respect for the institution of the House of Lords.

This was especially after the Conservative peers attempted systematically to block the progressive people’s budget of 1909 which introduced the first old age pensions.

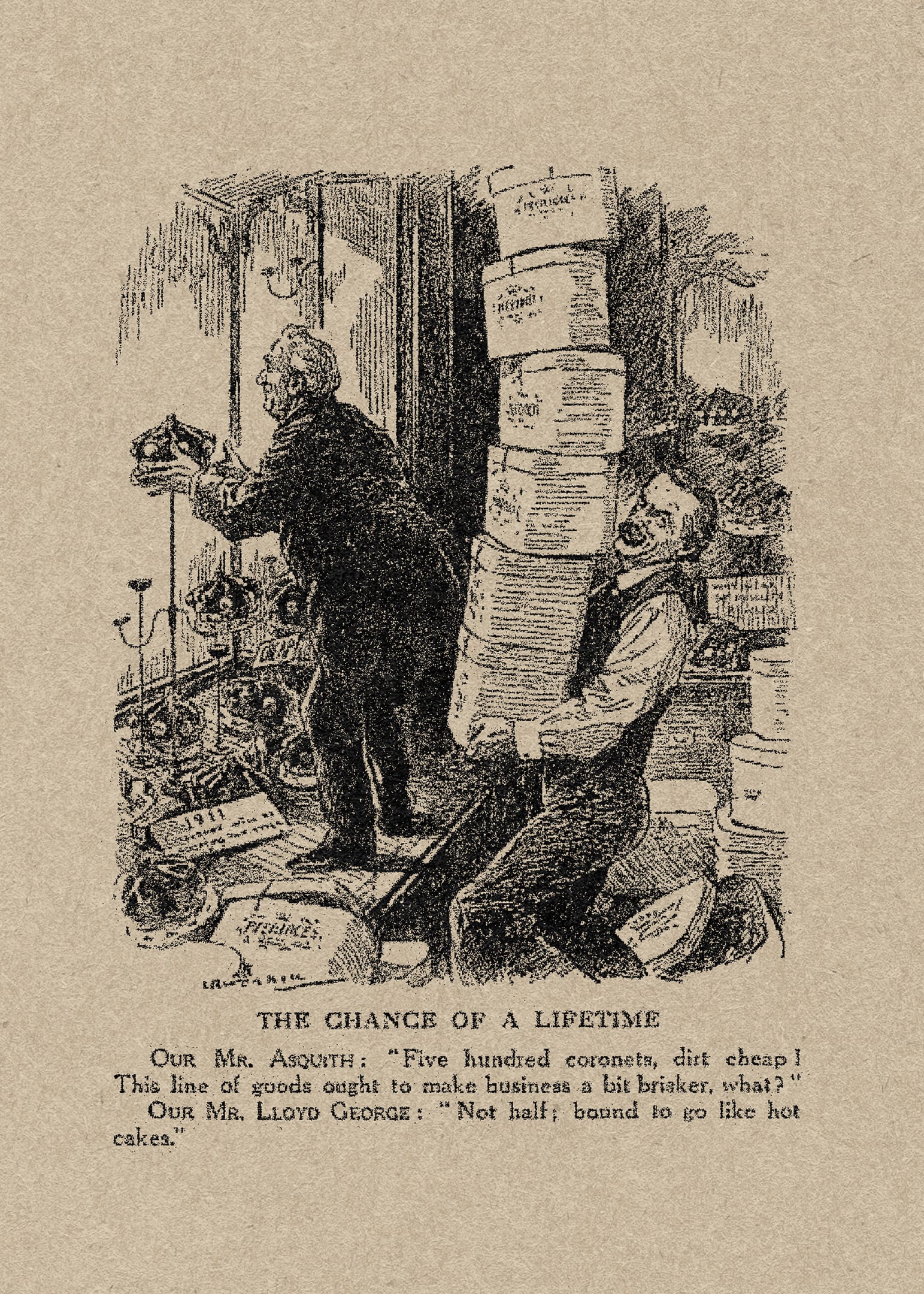

As Chancellor of the Exchequer and a brilliant orator, Lloyd George led the charge against the Upper House, which was composed, he said mockingly, of '500 ordinary men chosen accidentally from among the unemployed.' They didn’t think much of him either.

By December 1916 however he himself was reliant on Tories to sustain the wartime coalition government, after he supplanted Herbert Asquith in an internal coup.

The move split the Liberal Party with many of its MPs continuing to side with the former prime minister. Lloyd George and the majority Tory coalition that he led, however, won the so-called 'coupon election' held immediately after the end of the war.

It gained this name because Liberal candidates who supported him were authorised with a letter to stand as official coalition candidates.

The coalition continued into the first years of peace but Lloyd George and his coterie of supporters realised that to sustain his electoral power he needed to raise funds: he did not have access to as many wealthy donors as the Tories.

The prime minister himself, often out of the country attending the Versailles Peace Conference or other international events, was not too concerned about how the money was obtained and did not bother with the details, which were left largely to his chief whip Captain Freddie Guest.

As such, Lloyd George saw very little wrong with cash for honours. Years later he told a Tory MP:

'You and I know perfectly well it is a far cleaner method of filling the party chest …Here a man gives £40,000 to the party and gets a baronetcy. If he comes and says you must do this or that, we can tell him to go to the devil. The worst of it is you cannot defend it in public, but it keeps politics far cleaner than any other method of raising funds.'

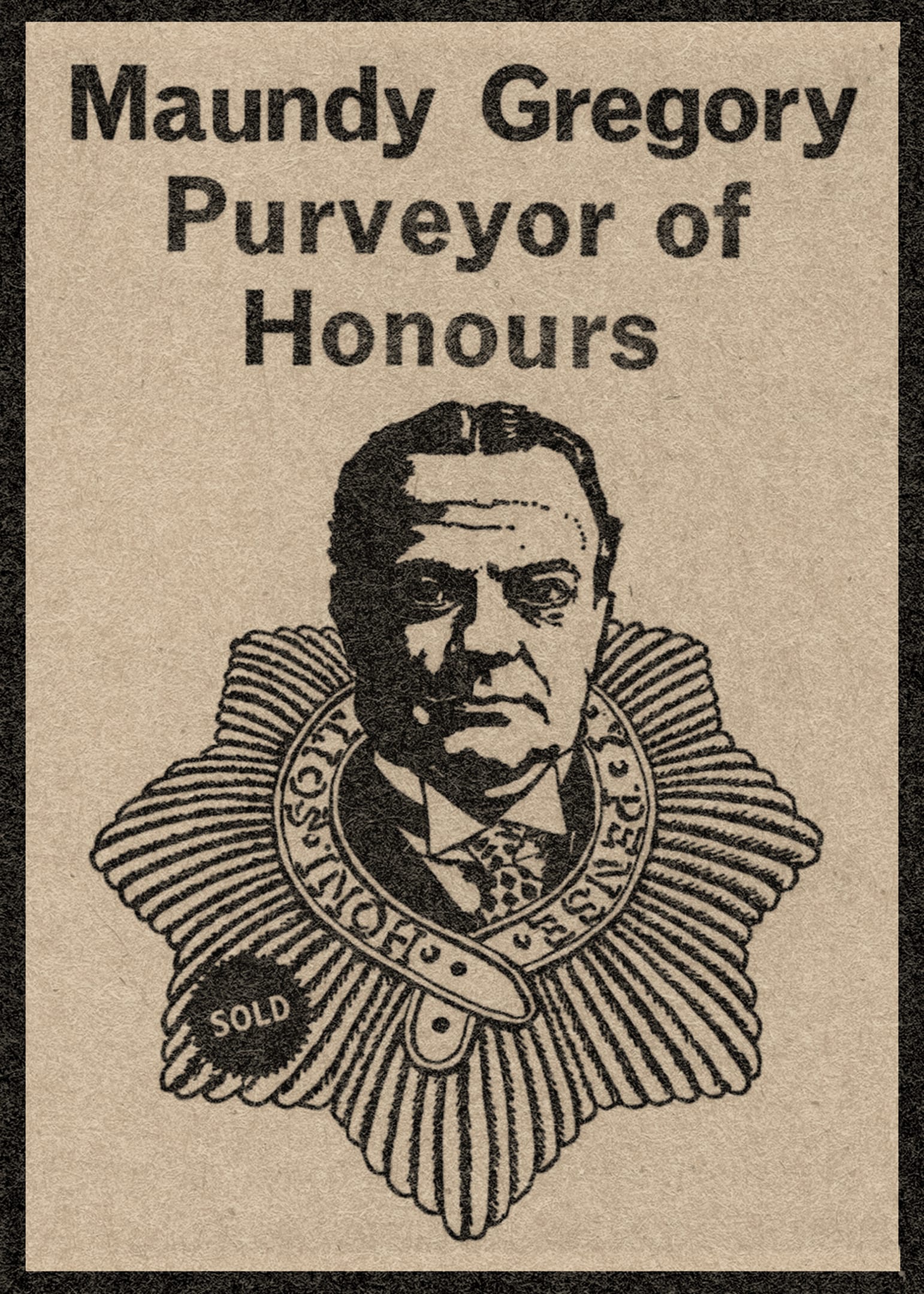

Enter, at this point, Arthur John Peter Maundy Gregory as the king of the Honours Touts. He was employed by Guest to raise money. On the surface he was a strange choice. Gregory was a chancer who had had a series of vaguely shady careers: a failed actor and impresario, a theatre manager, a magazine editor specialising in persuading people to pay for puff pieces about themselves in its pages and, during the war, a would-be spy and police informer.

It was his contacts and his ability to smooth talk potential clients that made him so effective. He set up openly in an office on Whitehall, opposite Downing Street, and for several years raked in a handsome living in commissions: £30,000 a year, it was said.

He was successful until the coalition government inevitably fell – the Tories did not trust Lloyd George and they were also suspicious of Gregory’s fund raising, stealing money from donors they thought should be theirs – 'Freddy is nobbling our men!' complained the Tory party chairman.

The Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act was passed in 1925 but in its century-long existence Maundy Gregory has been the only person ever prosecuted under it.

Gregory went to prison for seven weeks and was fined £50. When the sentence was up, a taxi met him at the gates of Wormwood Scrubs and whisked him off to the ferry to exile in Paris, where he was paid a monthly pension to keep his mouth shut about who had bought their honours.

The full story of Maundy Gregory and his bizarre career, rise, downfall and sticky end, is told in my new book: The Man who sold Honours, published this month by Icon Books •

This feature was originally published November 24, 2025.

A regular broadcaster, he has also written for The Spectator, New Statesman, Time, Literary Review, Tablet and BBC History Magazine, Le Monde and Berliner Zeitung. He is married with three adult children and lives in Kent.

The Man Who Sold Honours: The First Modern Cash for Honours Scandal

Icon Books, 20 November 2025

RRP: £18.99 | ISBN: 978-1837730278

In The Man Who Sold Honours, Stephen Bates lifts the lid on the truth about this long-forgotten character who remains the only person ever to be prosecuted under the sale of honours act of 1925. A powerful preview of the scandals to come in Britain in recent years, this is the story of the original honours tout - a riches-to-rags tale of greed, corruption and murder in the interwar years.

Paying for a peerage – an illegal practice – feels like a very modern form of corruption, one that both the Labour and Conservative parties have been accused of indulging in at times during the early twenty-first century. Except, of course, it was happening almost a century ago.

Meet Maundy Gregory, actor, journalist, publishing proprietor, conman, embezzler, MI5 spy – and the man you went to see if you had the money to pay for a peerage in the post-First World War years.

Cutting a dash across high society of the 1920s – he was in attendance at the wedding of the future George VI – the immaculately oiled and overdressed Gregory would happily pocket thousands for playing Mr Fixit for wannabe knights and lords, and swell the coffers of Lloyd George's Liberal Party to millions of pounds.

Business was brisk, and business was brazen. Visitors to his lavish office on Parliament Street, with a direct line to 'Number 10', would be wined and dined and, after paying up, leave satisfied that they would be next on the list for a knighthood or barony. Nothing could be guaranteed, of course, and it was a strictly no refunds business.

But Gregory was also suspected of being something else, to add to his impressive list of accomplishments: a murderer. As the political winds changed, the debts mounted up and the walls closed in around him, he somehow managed to inherit his mistress's not inconsiderable savings when she scribbled a new will on the back of a menu and was suddenly taken ill...

“Unfailingly perceptive on context as well as character, this highly readable portrait of one of the most notorious fixers of modern British political history is likely to be definitive”

– David Kynaston

With thanks to Elle-Jay Christodoulou.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store