My Lost Friend

Shafik Meghji evaluates the history and cultural legacy of Rapa Nui's moai

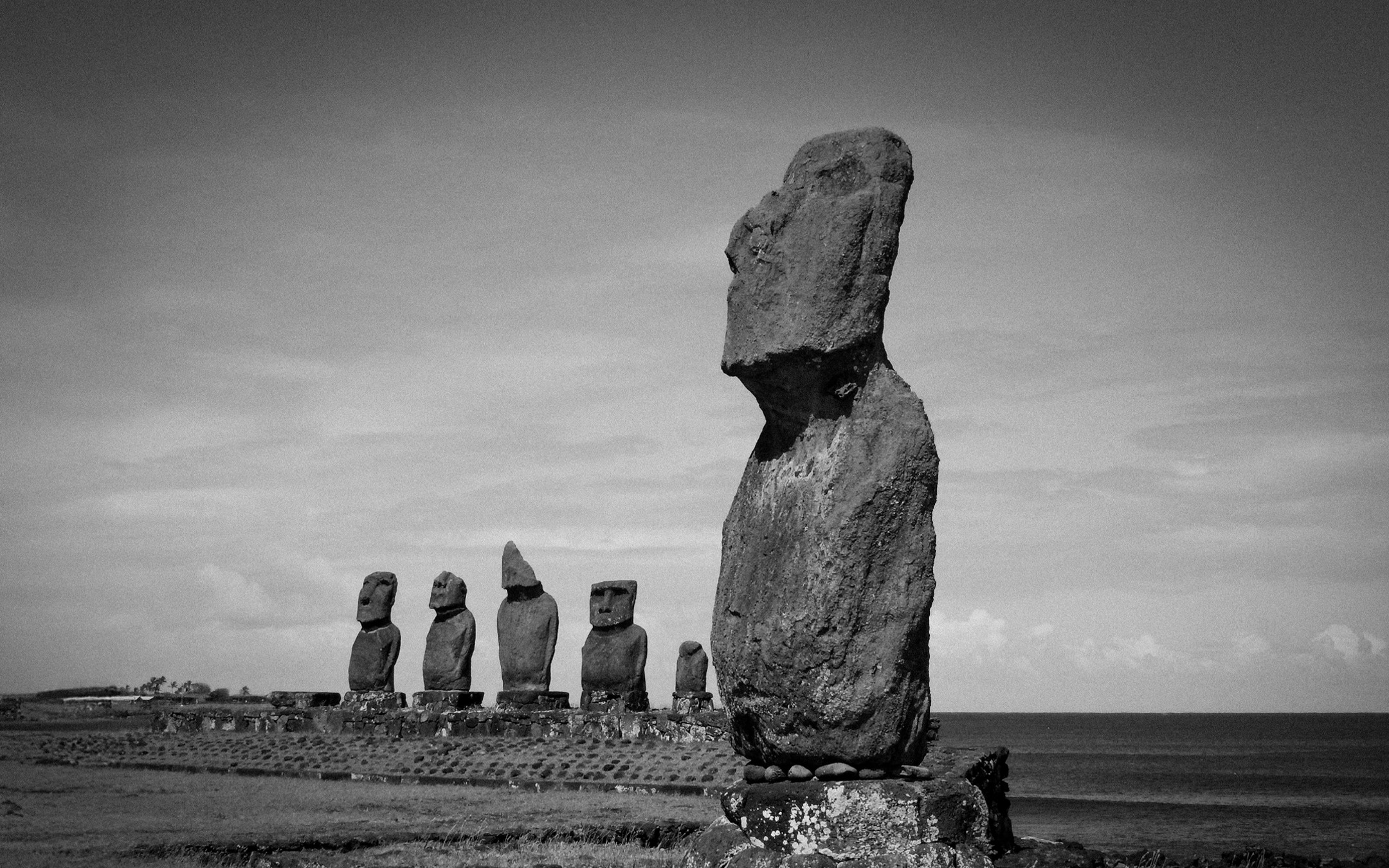

Upon one of the most remote islands on the planet stand some of the most compelling and enigmatic of all monumental statues. These are the 'moai' of Rapa Nui, a place long known in the West as Easter Island.

Shafik Meghji, the author of a new book on South American history, Small Earthquakes, takes us on a visit to Rapa Nui. In so doing he finds the origin of a 'lost friend', one he first encountered far away in London.

The Te Ara O Te Ao trail ascends across a rippling grassland to the crater rim of an extinct volcano before arcing towards the ruins of a village called Orongo. Rows of low, oval-shaped basalt structures line the site. With sheer cliffs in front and the seemingly endless Pacific beyond, Orongo feels like it sits on the edge of the world.

For around 150 years, young men walked the trail during the Tangata Manu, or Birdman, contest. From Orongo, they scaled 1,000-foot cliffs, swam through treacherous waters and waited patiently on a rocky islet for the first sooty tern egg of the season. The patron of whoever claimed this prize became the Tangata Manu, Rapa Nui’s spiritual leader for the next year.

The contest lasted until 1867, when missionaries put an end to it. Displays at the visitor centre emphasised Orongo could also disappear, as erosion makes parts of it unstable. Despite the history, scenery and sense of remoteness, I was most struck by an absence, an empty space in a large building that once held Hoa Hakananai’a, one of Rapa Nui’s iconic moai.

More than eight feet tall and decorated with Tangata Manu symbols, the statue is held at the British Museum. He was the first moai I saw in the flesh, an experience that helped to fire a life-long love of South America before I was old enough to question why the statue was there in the first place.

In the Rapanui language, I later learned, Hoa Hakananai’a means ‘lost, hidden or stolen friend’.

A triangular speck of land in the middle of the Pacific, Rapa Nui is the world’s remotest inhabited island. Its nearest inhabited neighbour is Pitcairn, around 1,200 miles to the west.

The Chilean mainland, in turn, lies more than 2,200 miles to the east. Home to some 7,750 people, half of whom are Rapanui, the island was settled in 800-1200 CE by Polynesian navigators who voyaged across thousands of miles of uncharted ocean. In splendid isolation, they embarked on a bout of statue carving – an expression of ancestor worship – for half a millennium or more.

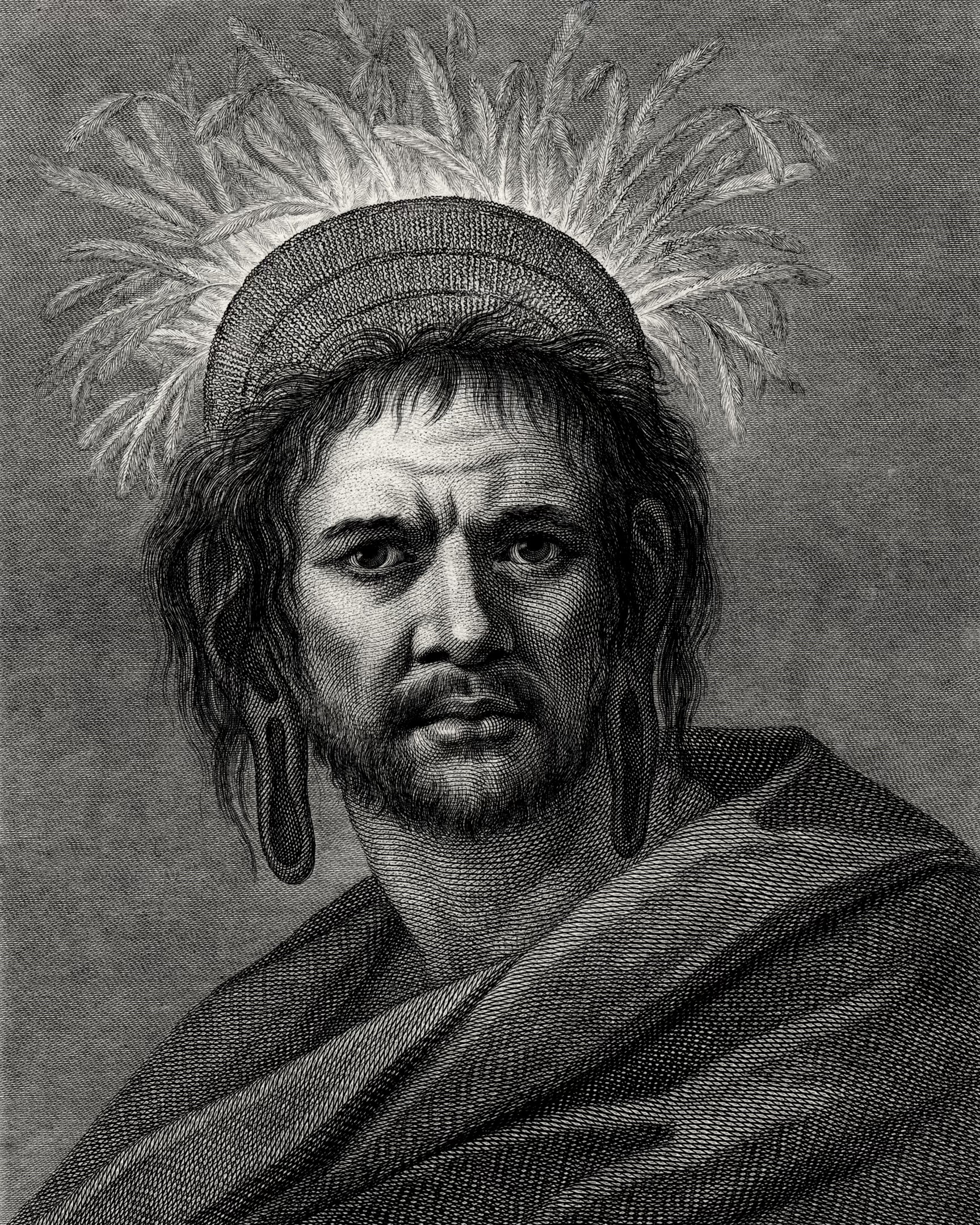

English pirate Edward Davis, captain of the Bachelor’s Delight, may have been the first European to spot Rapa Nui in 1687. But the first confirmed contact came 35 years later, when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen sighted the island on Easter Sunday, 1722 – hence Easter Island.

It was half a century before the next European visitors. In 1770, an expedition led by Felipe González de Ahedo ‘claimed’ the island for the Spanish crown. Four years later, James Cook arrived on the Resolution, but was so ill he only briefly set foot on the island. His crew explored the coastline, exchanged goods and reported the Rapanui appeared short of supplies, suggesting there may have been recent unrest.

The 18th century was undoubtedly a period of rupture. Conflicts – probably driven by a combination of European contact, power struggles, scarcity of food and other resources, and a loss of faith in the power of the moai – brought statue carving to an end, and every moai was toppled. In response, the Rapanui developed a new way to restore order: the Birdman contest.

For many beyond its shores, Rapa Nui is synonymous with ecocide, a contentious theory long been challenged by the Rapanui and widely contradicted by scientific research. The story of the Rapanui is one of resilience against almost insurmountable odds – not only to reach the island in the first place but to withstand devastation, exploitation and disease.

During the mid-1800s, around 1,500 islanders were kidnapped in Peruvian slaving raids and forced to mine guano, an immensely valuable fertiliser, whose trade was dominated by British firm Antony Gibbs & Sons.

The population was further devastated by smallpox and tuberculosis epidemics. Meanwhile, Christian missionaries curtailed their culture, including the Birdman contest.

On a recent visit, I stayed in a guesthouse hidden down a warren of lanes outside Hanga Roa. Rapa Nui’s miniature capital is an attractive, tranquil town, but once resembled a ghetto. In the late 1860s, rapacious ranchers arrived and ran the island as a personal fiefdom. They included Alexander Ari‘ipaea Salmon, scion of a powerful British–Jewish–Tahitian dynasty.

In 1888, Chile annexed Rapa Nui – nudged along by British diplomats – and attempted to settle families on the island. When that plan failed, it leased the island to Chilean businessman Enrique Merlet. He instructed his foreman to build a 10-foot stone wall around much of present-day Hanga Roa, from which the Rapanui required a permit to leave. It essentially turned the village into a concentration camp.

This 19th-century turmoil decimated Rapanui society. Political and social structures were shattered, and the population plunged by around 95 per cent. The 1877 census recorded just 111 Indigenous islanders.

For an insight into the next phase of Rapa Nui’s history, I met guide and author James Grant-Peterkin, who lived on the island for two decades until 2023, serving as the British honorary consul.

Over coffee, he explained Merlet’s lease was acquired by Williamson, Balfour & Co, a Scottish-founded Chile-based company with interests in nitrate and wool, in 1903. Its concession, the bluntly titled Easter Island Exploitation Company, turned the island into ‘a giant sheep ranch, bringing the animals over from Chile and the manager, administrator, vets and so on from Britain’.

At one stage, there were 70,000 sheep corralled by Scottish-style stone walls built from moai ceremonial platforms. The repression of the Rapanui continued, provoking a series of uprisings. A first-hand account was provided by British archaeologist and anthropologist Katherine Routledge, who spent 16 months carrying out research on the island.

Her visit was eventful, to say the least. Shortly after arriving in 1914, she witnessed a ‘curious development… which turned the history of the next five weeks into a Gilbertian opera’. Led by an elderly woman named Angata, a group of islanders declared ‘war’ on the company, raised a flag marking their new ‘republic’ and seized livestock. The uprising was only thwarted by the arrival of the Chilean Navy.

Soon afterwards, Rapa Nui became the site of geopolitical conflict. On 12 October, a German fleet commanded by Admiral Maximilian von Spee arrived. Routledge’s party did not know the First World War had broken out, and von Spee kept the news to himself. He had earmarked the island as a covert rendezvous spot.

Initially, relations were cordial but the bonhomie ended when a crewman let news of the conflict slip. The squadron had stayed longer than the 24 hours permitted in a neutral port, prompting Routledge to write an angry letter in protest.

Mysteriously, the Chilean representative on Rapa Nui – the schoolmaster – managed to persuade von Spee to depart.

During the chaotic 1930s, Chile considered selling Rapa Nui, with Britain mooted as a potential buyer. Ultimately, Williamson, Balfour & Co’s lease was extended but the wool industry was declining. Meanwhile, the Rapanui remained in appalling conditions. Many risked their lives in small boats on the perilous Pacific rather than stay on the island. Others staged protests and strikes.

In 1953, Williamson, Balfour & Co’s reign came to an end. Chile assumed control but a civil rights movement was growing among the islanders. In 1965, the Rapanui elected their own mayor, and the following year won full Chilean citizenship and the right to vote in national elections.

Williamson, Balfour & Co’s impact can still be felt today, as its sheep did lasting damage to the local environment. Beyond a few Rapanui families with British surnames, the ‘only physical remnants of that time are a few rotting outhouses’, said Grant-Peterkin.

Yet the British presence lives on in the Rapanui language, he added. Under Williamson, Balfour & Co, islanders came up with names for the new items they encountered. As all Rapanui words end in a vowel, hammer became ‘hamara’, blanket ‘prankete’, onion ‘oniana’, beer ‘pia’ and book ‘puka’.

Back in London, I visited Hoa Hakananai’a in the British Museum’s ‘Living and Dying’ gallery. He was taken from Orongo in 1868 by Commodore Richard Powell, captain of HMS Topaze, before being gifted to Queen Victoria, who passed him on to the British Museum.

There are moai in museums worldwide, while around 900 remain on Rapa Nui. But Hoa Hakananai’a is particularly significant. He is one of only a handful sculpted from basalt – most are made from softer lapilli tuff – and his unique petroglyphs provide an insight into the Birdman religion.

There are growing calls for his return. A British Museum statement ‘recognises the significance’ of the moai to the Rapanui. But there are no plans for repatriation . This inaction prompted a grassroots Chilean campaign to bombard the museum’s social media accounts in 2024 with the message ‘return the moai’.

The situation was summed up by Anakena Manutomatoma, who serves on Rapa Nui’s development commission. He told the BBC: ‘The British taking the moai from our island is like me going into your house and taking your grandfather to display in my living room.’ •

This feature was originally published July 25, 2025.

Small Earthquakes: A Journey Through Lost British History in South America

C Hurst & Co, 31 July, 2025

RRP: £25 | 304 pages | ISBN: 978-1805264033

Small Earthquakes uncovers the fascinating story of Britain's forgotten connections with South America, from the Atacama Desert to Tierra del Fuego, Easter Island to South Georgia.

Blending travel writing, history and reportage, award-winning journalist and author Shafik Meghji tells a tale of footballers and pirates, nitrate kings and wool barons, polar explorers and cowboys, missionaries and radical MPs. From a ghost town in one of the world's driest deserts to a far-flung ranch in the sub-polar tundra; rusting whaling stations in the South Atlantic to an isolated railway built by convicts; the southernmost city on the planet to a crumbling port known as the 'Jewel of the Pacific', he brings to life the past, present and future of this remarkable continent.

He sheds light on Britain's impact on Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, from sparking wars, forging national identities and redrawing borders to its tangled role in their colonisation and decolonisation. But it also reveals how these countries, in turn, have shaped Britain in profound and unexpected ways, from Fray Bentos to the Falklands.

Drawing on more than fifteen years of living, working and travelling in South America, Meghji offers a sweeping account of an overlooked--but enduringly relevant--shared history.

“The passion and poignancy of his prose is captured in his description … Combining the immediacy of a travel memoir with the depth of a scholarly history lesson, Small Earthquakes illuminates how Britain helped shape these nations.”

― BBC Travel, ‘Six Upcoming Summer Travel Books’

“A fascinating—and often shocking—book full of hidden histories and unlikely characters: guano barons, gaucho lairds, imperial ghosts and human zoos. Shafik Meghji must be one of the most exciting travel writers working today.”

― Cal Flyn, author of Islands of Abandonment

With thanks to Hurst Publishers.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store