The Summer of 69 (Part 1 of 2)

The Moon landings gave the summer of 1969 its defining story. But elsewhere in the world many other events of consequence were playing out

The summer of 1969 brought the most thrilling journey in the history of humankind. That July the astronauts of the Apollo 11 mission realised President John F. Kennedy's ambition of landing on the Moon and returning safely to Earth.

In this photographic essay, we follow the story through the anxious weeks of preparation, towards the landings and onto the crowning moment of triumph, on 24 July, when the returning astronauts splashed down safely in the Pacific.

The Moon landings gave the summer of 1969 its defining story. But elsewhere in the world many other events of consequence were playing out.

Looking back at these stories, fifty-five years later, we can glimpse a vivid moment in human history when culture, politics and science were all charged with a powerful, restless energy.

Words by Peter Moore

With curated and remastered images from the public archives by Jordan Acosta

1/91

30 March 1969 – Faces of the real men in the moon

This official mission photograph was taken at the end of March. Over the preceding months the names 'Neil Armstrong', 'Edwin Aldrin' and 'Michael Collins' had started to appear in newspapers with increasing regularity. This photograph marked an important moment in the three men's transformation from private citizens to public figures.

By January it was being reported that Armstrong (left), a civilian employee of NASA was to be the flight commander and, if all went well, the one who would first step on the Moon. Air Force Colonel Edwin Aldrin (right), who was affectionately known as 'Buzz', was to pilot the lunar landing craft while Michael Collins (centre) was to remain in lunar orbit in Apollo 11.

Collins was to rendezvous with Armstrong and Aldrin once their landing tasks were completed and the three were to return together to Earth.

2/91

2 March 1969 – Concorde aloft

Throughout the 1960s the acceleration of the US space program had seen America outpace the old European powers in terms of technological innovation. When it came to commercial aircraft design, however, Britain and France still claimed a lead over the United States of as much as six years.

The proof of this claim was the joint, Anglo-French Concorde project. On a blustery, foggy day at Toulouse Airport in France, the supersonic airliner, 'with its drooping nose', made its maiden flight.

In an important precursor to what would happen later in the year, millions watched Concorde's take-off live on television. The aeroplane was under the control of test pilot Andre Turcat and it performed perfectly. 'It soared', ran one report, 'into the cold winter sky, looking for all the world like a giant bird of prey'.

For those whose imaginations were caught by Concorde's maiden flight, there was to be a follow up the next day. On 3 March Apollo 9 launched from Florida. A ten day mission, it carried three astronauts all the way to the Moon.

Later described as 'demanding, dangerous, crucial to the success of the program, [it was] also perhaps the most anonymous of the Apollo missions'. '

Everything', one NASA official wrote of Apollo 9, 'worked like a dream’.

3/91

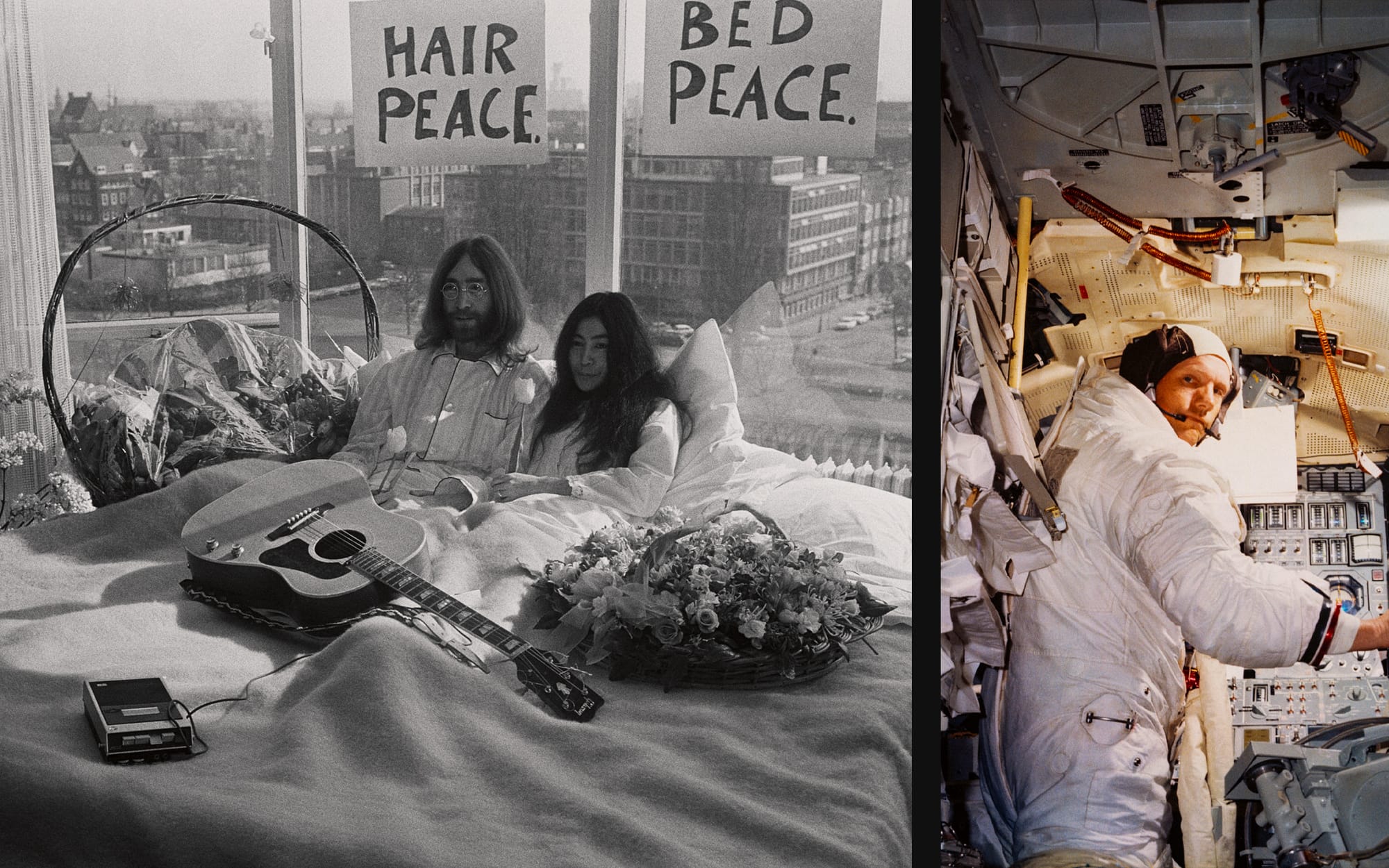

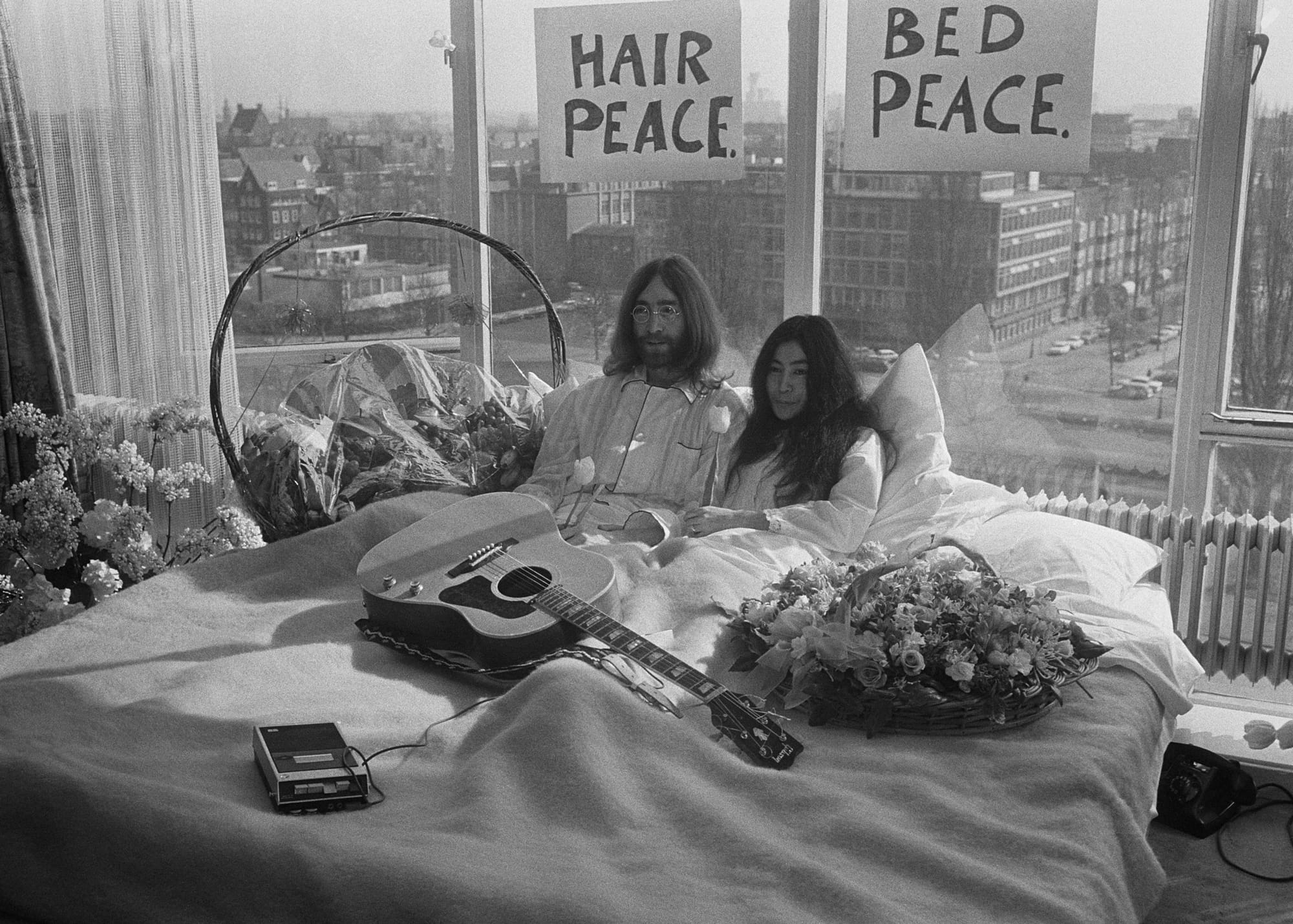

25 March 1969 – The 'Bed-bound "Happening"'

With the Get Back sessions over and the roof top concert performed, John Lennon left the fractious atmosphere of the Beatles behind. On 20 March he married Yoko Ono at a registry office in Gibraltar. The next week the newly wed couple invited the world's press to join them at a 'Bed In' at their honeymoon suite in Amsterdam.

The Daily Mirror sent their reporter Donald Zec across the Channel to report on the event. 'I know people will ask what am I doing with this Japanese screwball', Lennon told Zec, whose report was published on 31 March.

'This daft, hairy and faintly ugh inducing charade ends today', Zec wrote, 'And it may not have escaped your notice that tomorrow is April Fools Day.'

(⇲ Wiki Commons) / (⇲ NASA)

4-5/91

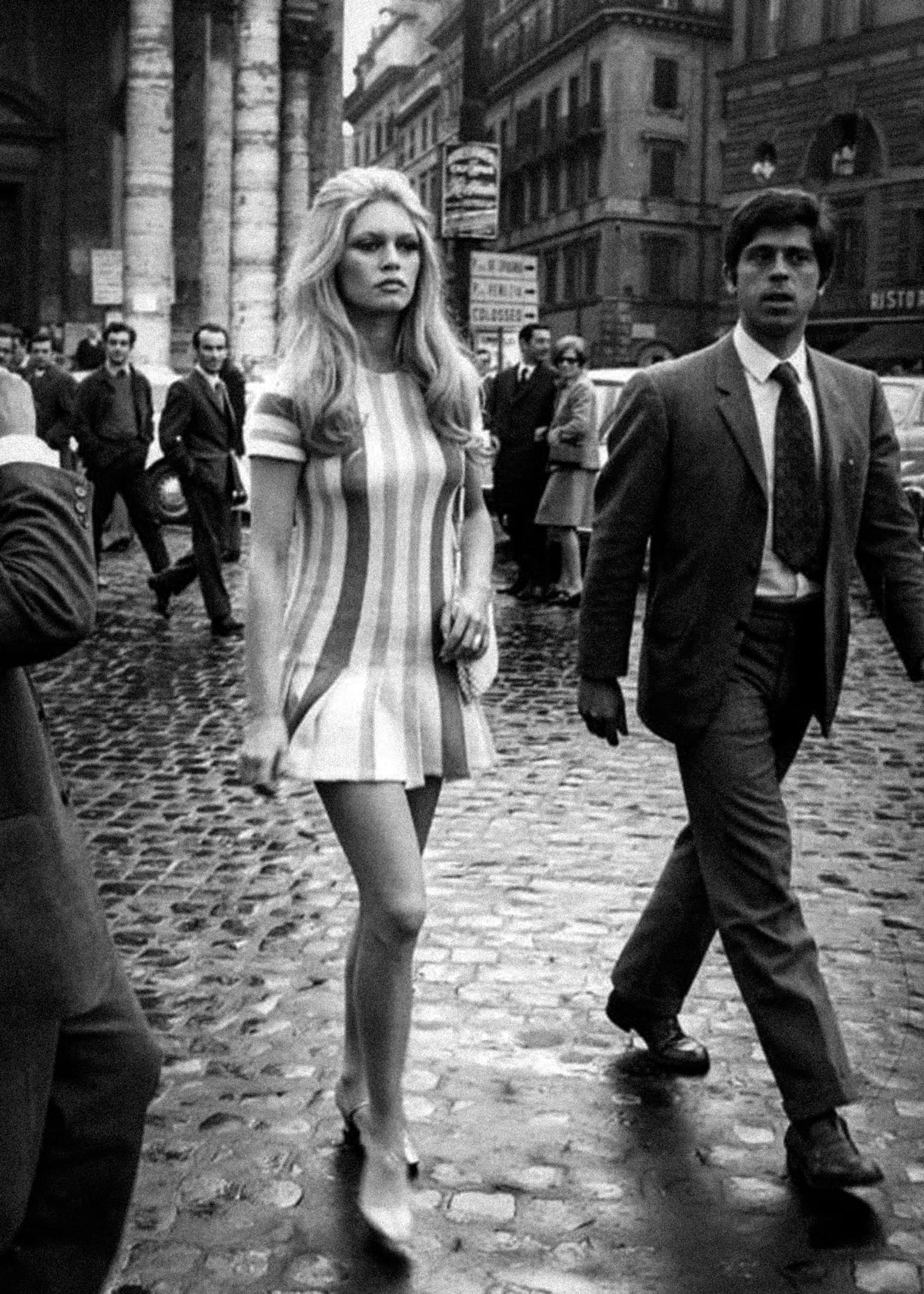

April 1969 – Brigitte Bardot

Brigitte Bardot, the French actress, was another dominating cultural figure of the decade that was drawing to a close. But as with Lennon, the press were treating her with much less reverence by 1969.

Her latest film Shalako provided critics with more evidence that Bardot's relevance was waning. At a time when culture was increasingly obsessed with technology and the future, Shalako was a Western that gazed back to the 1880s.

Co-starring Sean Connery, who was fighting against his typecasting as 'James Bond', most agreed that Shalako did not 'add up to very much'.

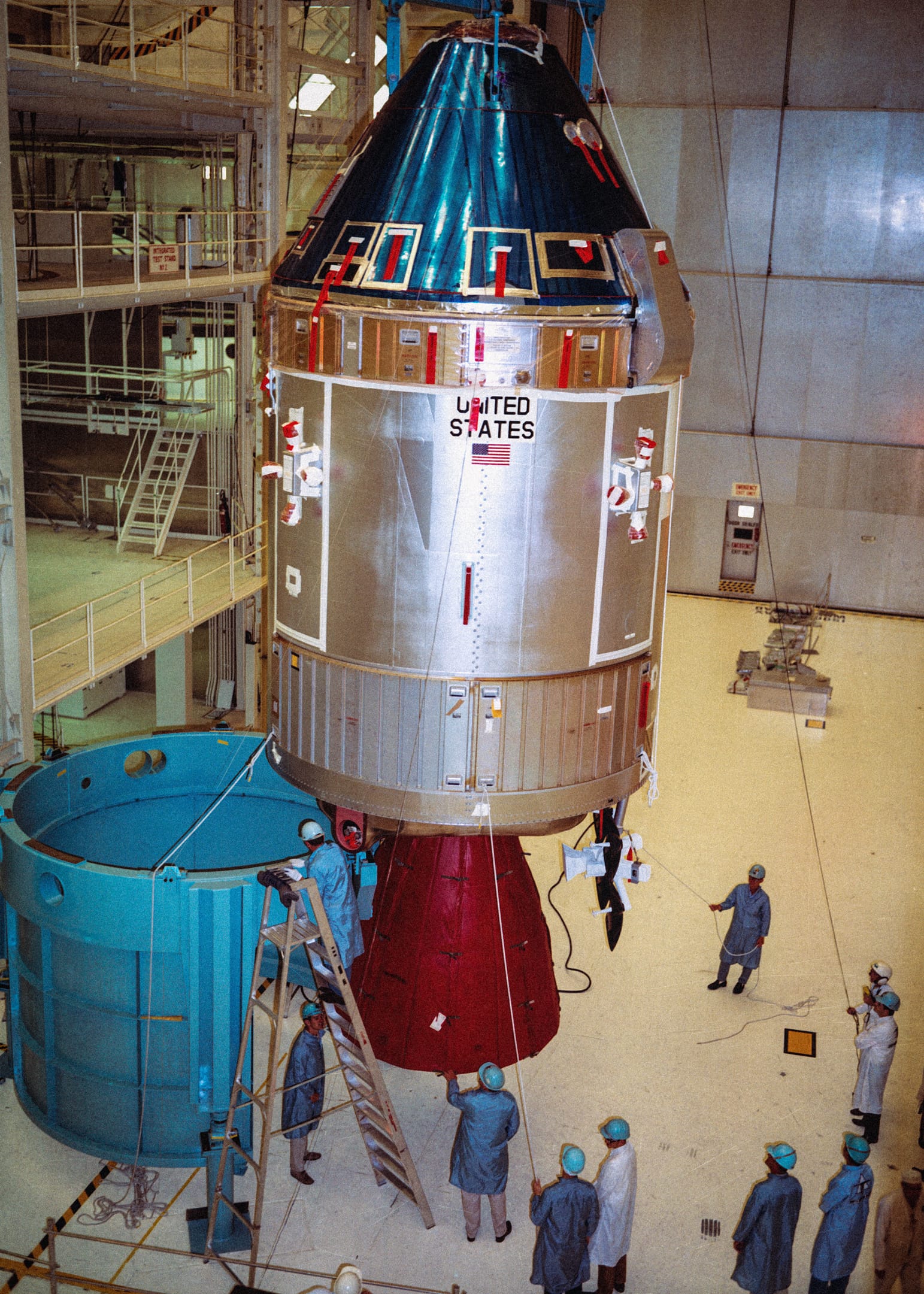

Meanwhile, at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida (right), work on the Command and Service Module (CSM) was complete.

6/91

15 April 1969 – EC-121 shoot-down Incident

After the terrifying confrontations of the early 1960s, the Cold War had settled into a more stable phase by 1969. Nonetheless, the Americans and Russians kept a wary eye on each other. A system of spy satellites was constantly encircling the globe, gathering images from either side of the Iron Curtain and listening in to secret military conversations.

This surveillance network, however, was patchy. Its holes were plugged by spy planes like the EC 121 pictured above. On 15 April this craft was shot down over the Sea of Japan by the North Koreans. The missile strike resulted in the death of 31 Americans, causing a major diplomatic incident.

7/91

Spring 1969 – Vietnam

This gloomy photograph captures a scene that had become increasingly familiar to Americans throughout the 1960s. It showed American soldiers, many of them extremely young, deployed on a forbidding, faraway landscape. Something of the futility of the situation and of the determination of the soldiers is captured in this shot.

By the early spring of 1969 the numbers of dead had reached alarming levels. 7,000 North Vietnamese and Vietcong were estimated to have been killed during the first week of their latest offensive. In the same short period 370 Americans also died.

(⇲ Library of Congress) / (⇲ Library of Congress)

8-10/91

April 1969 – Anti war protests

Meanwhile another series of mass rallies were held in cities across the United States. Around 50,000 protestors gathered in Central Park, New York City, over the Easter weekend. Many of them wore black armbands, inscribed with the number 33,000 — the total number of American fatalities in the conflict so far.

Although anti-war protests had often taken place in US cities over the previous years, those of Easter 1969 were the first since the Nixon administration had entered the White House in January.

(⇲ Wiki Commons) / (⇲ Wiki Commons)

11-12/91

April 1969 – The Kennedy brothers

Long before he became the 37th president, Richard Nixon had served as Senator for California. As such he had particular reason to be looking back towards his home state in mid-April, as Sirhan B. Sirhan, who assassinated Robert F. Kennedy, was convicted of first-degree murder.

The twenty five year-old's case attracted huge publicity and after his conviction minds turned to the nature of his punishment. Sirhan's father, in Jordan, was quoted by the newspapers swearing 'revenge on American politicians if his son [was] executed'.

But a seven-man, five-woman jury decided that death was an appropriate penalty for political assassination. 'Sirhan in open-necked blue shirt and light grey trousers chewed gum as he listened calmly to the verdict', reported one newspaper.

As the legacy of one Kennedy was dealt with, at NASA the promise of another was weighing heavily. In May 1961 President John Kennedy had, in a surge of ambition, delivered an extraordinary address to Congress:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth. No single space project in this period will be more exciting, or more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

Pictured to the right of Sirhan is Robert Gilruth. As Director of MSC (the Manned Spacecraft Center), the responsibility for turning Kennedy's aspiration into reality fell most of all to him.

On hearing Kennedy's speech in 1961, Gilruth described himself as 'aghast'.

13/91

April 1965 – Eugene F. Kranz during the Gemini-Titan 4 mission

Along with its astronauts, each Apollo mission was assigned distinct managerial personnel who would direct events from a control room. By April those on the 'G Mission' or Apollo 11 had been confirmed. Cliff Charlesworth was picked as the lead flight director. He, in turn, chose Eugene Kranz (pictured) as th director for the lunar descent phase of the mission.

Kranz came with a brilliant reputation. 'Gene was the guy you wanted on the headset when there was trouble', Charlesworth stated. 'When the term 'flight controller' is used, the first personal I think of is Kranz'.

14/91

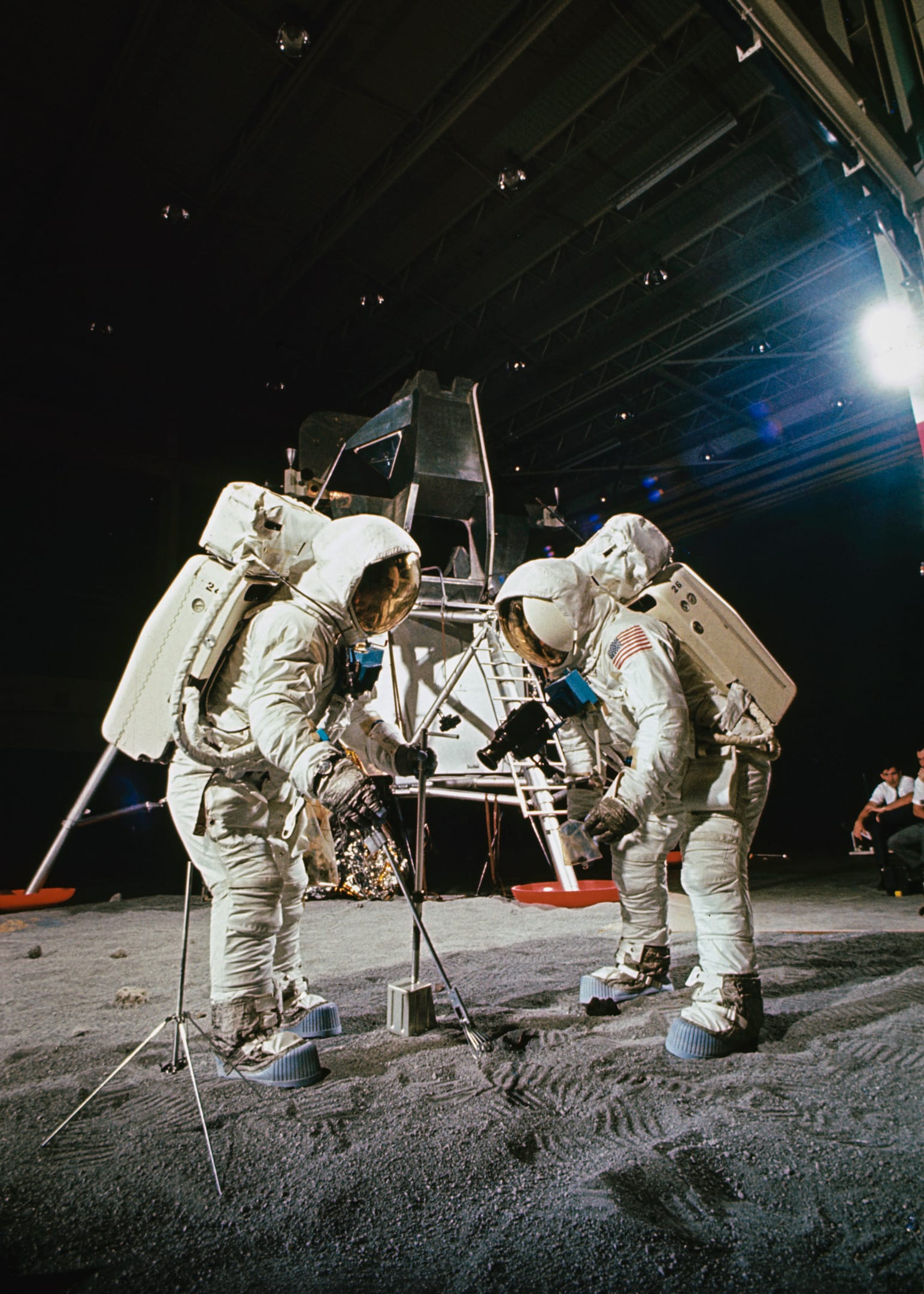

22 April 1969 – Two members of the Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission participate in a simulation of deploying and using lunar tools

By April the success of Apollo 9 had charged the space program with new energy. Coming into focus as the spring wore on were two crucial missions. '10', set for launch in May, would see the lunar module flown to within 50,000 ft of the Moon's surface. It would be an almost complete dress rehearsal for the actual landings, which were timetabled for July.

With the prospect of a Moon landing increasing, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were left to concentrate on their training exercises. This photograph shows them participating in a simulation during which they were required to use a range of specially developed tools. Armstrong is pictured on the right, Aldrin to the left.

(⇲ NASA) / (⇲ Wiki Commons)

15/91

May 1969 – Symbols of space

While a great deal of emphasis rested on the practical business of engineering and simulation, outside NASA people were also thinking about commemoration. If Apollo 11 should reach the Moon, what should be left there? On whose behalf should the astronauts act? The United States of America's or all humankind?

These questions remained open in the spring of 1969 but, in the meanwhile, some artefacts were already being prepared. Above to the left you can see a photograph of a six-inch golden olive branch. This message of peaceful exploration was to be one of the central themes of the mission.

In the Soviet Union a more traditional form of commemoration was being observed. To mark the arrival of their Venera 5 probe on the surface of Venus, a special stamp was issued.

For all the olive branch and postage stamp seemed benign objects, they were in fact highly politically charged ones. In May both of the Cold War superpowers kept a watchful eye on the other. In Britain some speculated that more was to be learnt from the Soviet mission than from the Apollo one.

'Many mysteries about the cloud-shrouded planet [Venus] may be answered', speculated one journalist.

16/91

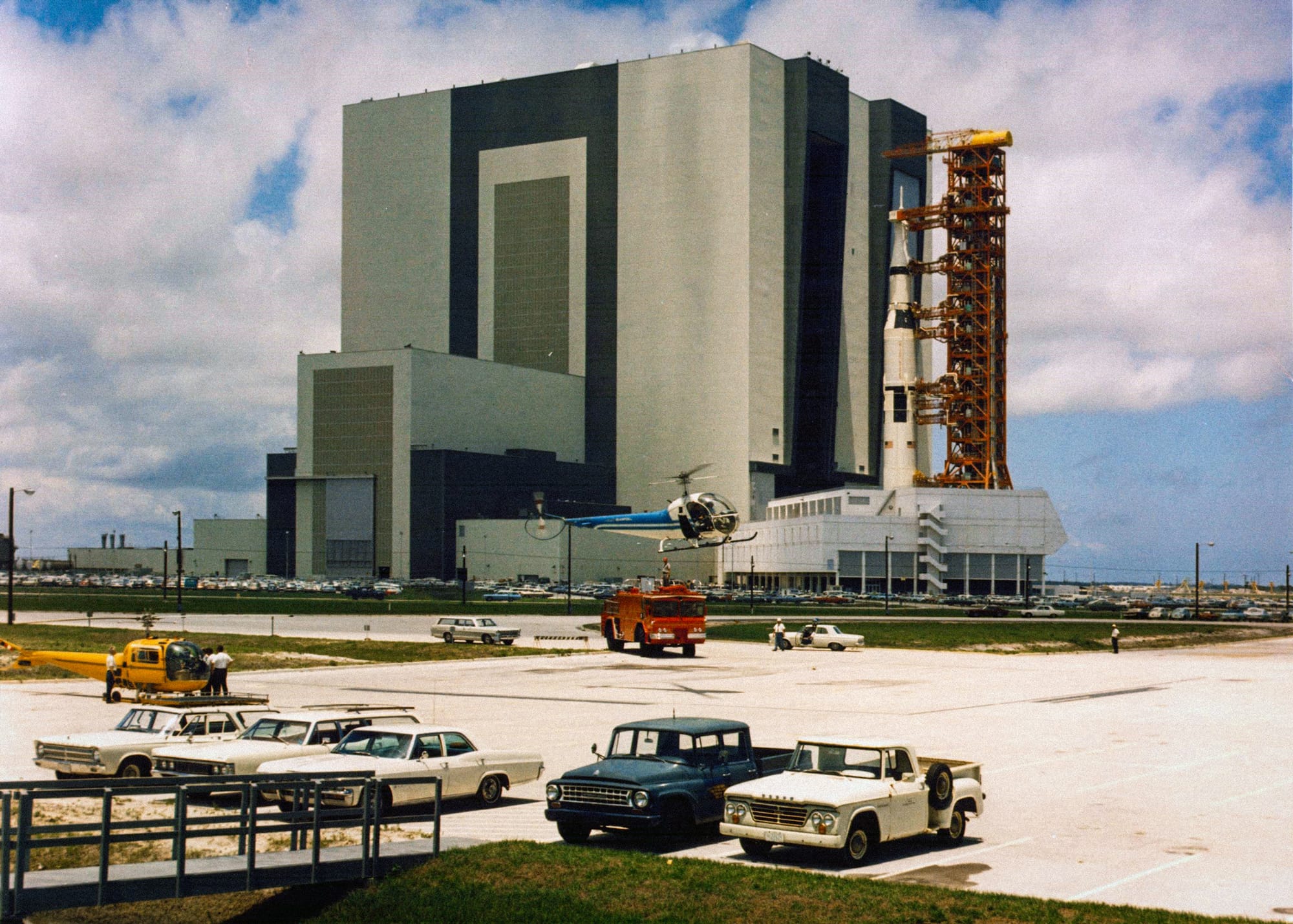

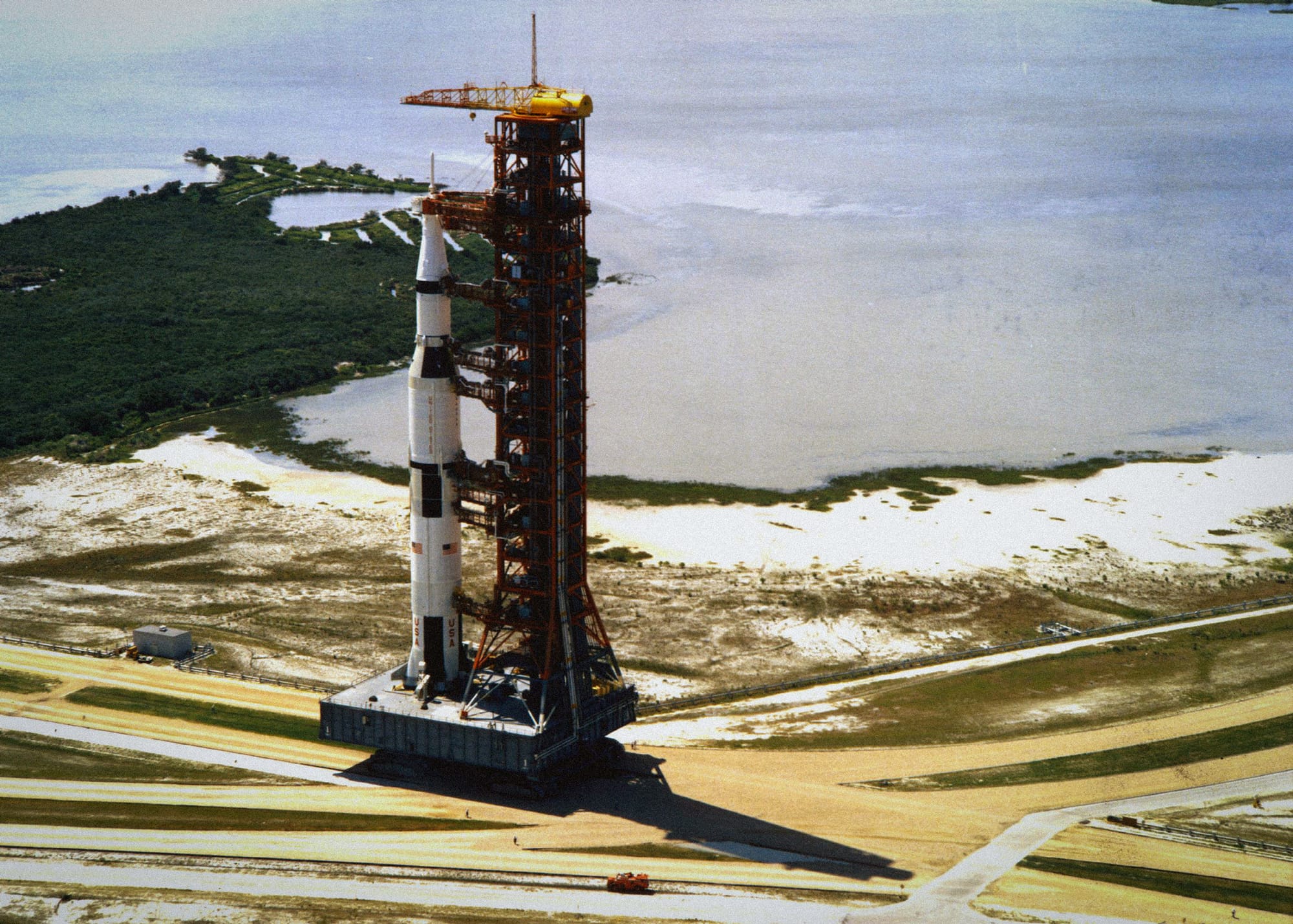

20 May 1969 – The Apollo 11 Saturn V Space Vehicle and Mobile Launcher

On 18 May Apollo 10 launched from the Kennedy Space Center. The mission, in the words of Michael Collins, 'would be as full a dress rehearsal as possible but not the real McCoy'. A few days later television viewers were being promised live footage of Apollo 10's approach 'to within nine miles of the Moon's surface'. The shots should, one broadcaster said, be 'breathtaking'.

While this drama was playing out in space, preparations were already beginning for the launch of Apollo 11. The Saturn V rocket can be seen above, emerging from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) in Florida.

17/91

20 May 1969 – Crawling towards the launchpad

The Saturn V rocket's journey to the launch pad would take a full seven hours. In this photograph the 363 ft rocket can be seen progressing at below one-mile-per-hour on its huge transporter.

(⇲ NASA) / (⇲ Wiki Commons)

18-19/91

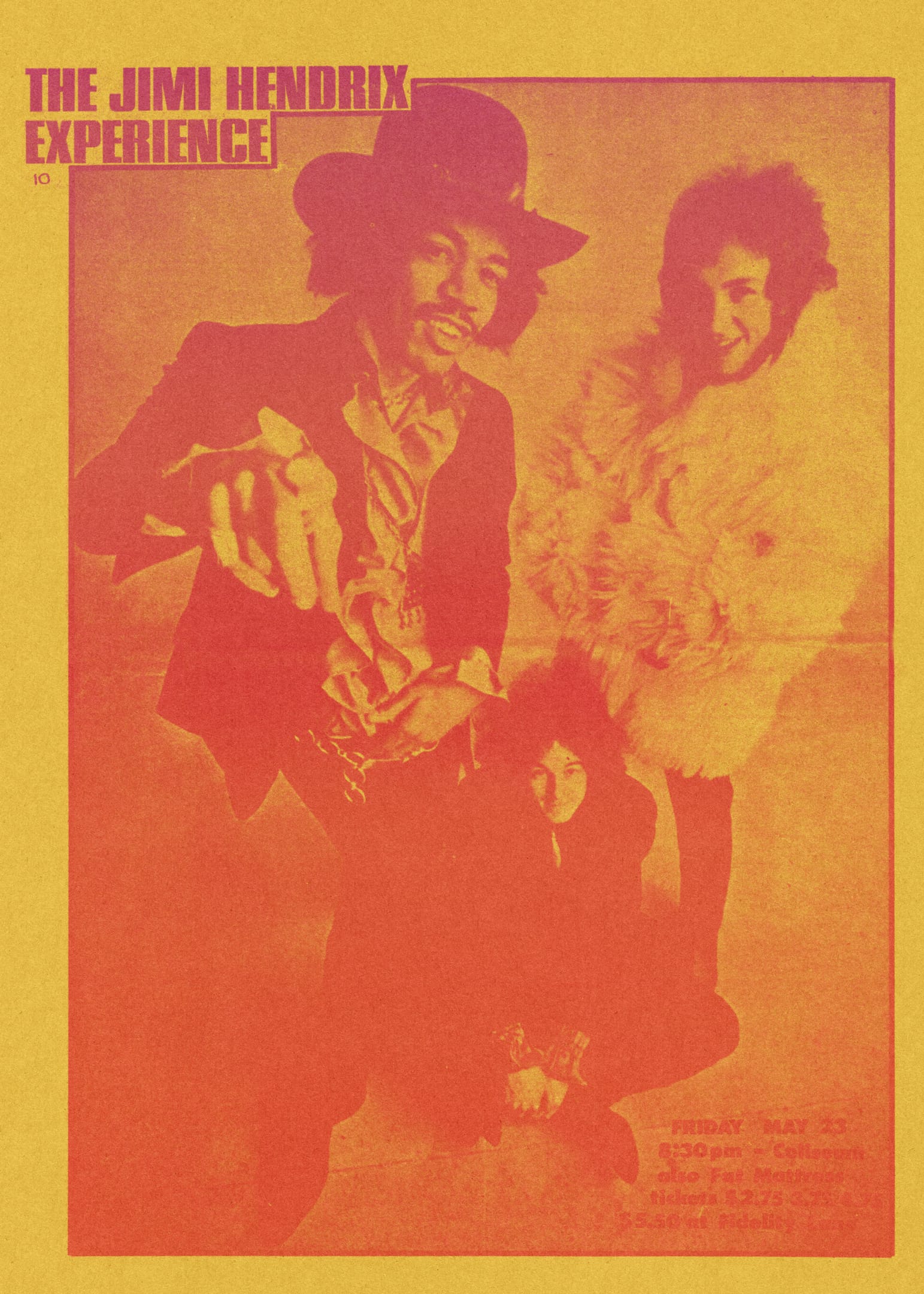

May 1969 – Culture & Counterculture

The 1960s, like no decade ever before, had seen the rise of distinctive group identities. No longer was it Elvis or Buddy Holly; it was the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Stones.

These two images play on this characteristic. To the right is a billboard promoting a concert by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, which took place on 23 May in Seattle. To the left is another group, although of a very different type. Buzz, Neil and Michael: the crew of Apollo 11. This photograph was taken on 24 May.

'The weeks seemed to fly by in the spring of 1969', wrote Michael Collins.

20/91

2 June 1969 – 'Michael Caine is back to form again'

Along with Apollo 11 and Concorde, one of the vehicles most powerfully associated with the 1960s is the humble mini. And at the start of June 1969, the car had its very own moment in the sunshine.

The film 'The Italian Job' was billed as a 'spoof comedy crime thriller', which tapped into a period craze (set by James Bond) for bizarre car chases. Caine, the protagonist, played a small time crook who planned a $4 million heist by 'engineering an elaborate traffic jam in Turin'.

As the Italian traffic ground to a standstill, so the minis leapt into life. Summing up, the Daily Mirror decided that 'Caine, Benny Hill, Irene Handl, Maggie Blye as Caine's cool chick, and particularly the urbane [Noel] Coward with his nonchalant authority stand out in a long, lively cast.'

21/91

3 June 1969 – Melbourne-Evans collision

As the precision simulations carried on in Houston and Florida, a training exercise in the South China Sea demonstrated just how perilous modern technology could be.

In the dead of night, the destroyer USS Frank E. Evans (pictured) became entangled with the Australian aircraft carrier Melbourne. The collision left seventy four on the destroyer dead.

Reacting to the tragedy, many dwelt on the unlucky series of accidents that had been connected to the Melbourne. Built by the British in Barrow-in-Furness in the last years of World War Two, it had lurched from one crisis to another over the past two decades.

The events of 3 June added credence to the verdict that it was a jinxed ship.

22-23/91

Summer 1969 – The fashion of the times

With such intense television coverage, space technology was primed to have a powerful and lasting effect on fashion. Here (left) in a photograph taken on 16 June, we can see a spill over from astronaut equipment to street fashion.

There would be much more of this to come over the years ahead, as the broader effect of the Apollo missions manifested itself in film and music. In the meantime, in the summer of 1969, the beaches of Florida filled up with sunseekers. It was from these beaches that so many would witness Apollo 11's launch in July.

For many this was a liberating time, although for some more conservative minds there was cause for anxiety. That summer Pope Paul would publicly deplore the 'nude look on summer holiday beaches'.

'He spoke', reported one newspaper, 'of swimsuit fashion and other holiday "excesses" at his usual Sunday mid-day blessing of pilgrims'.

24-25/91

Late June 1969 – Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins simulating tasks

Meanwhile the endless hours of practice continued for the astronauts. Here you can see Armstrong and Collins in their spacesuits, simulating the procedures that they would soon be performing in space.

An exciting moment arrived for the pair on 17 June when, after a nine hour formal meeting of NASA senior management, the launch date of 16 July was confirmed. After so many months they now knew with certainty that, within a month, they would be on the way to the Moon.

26/91

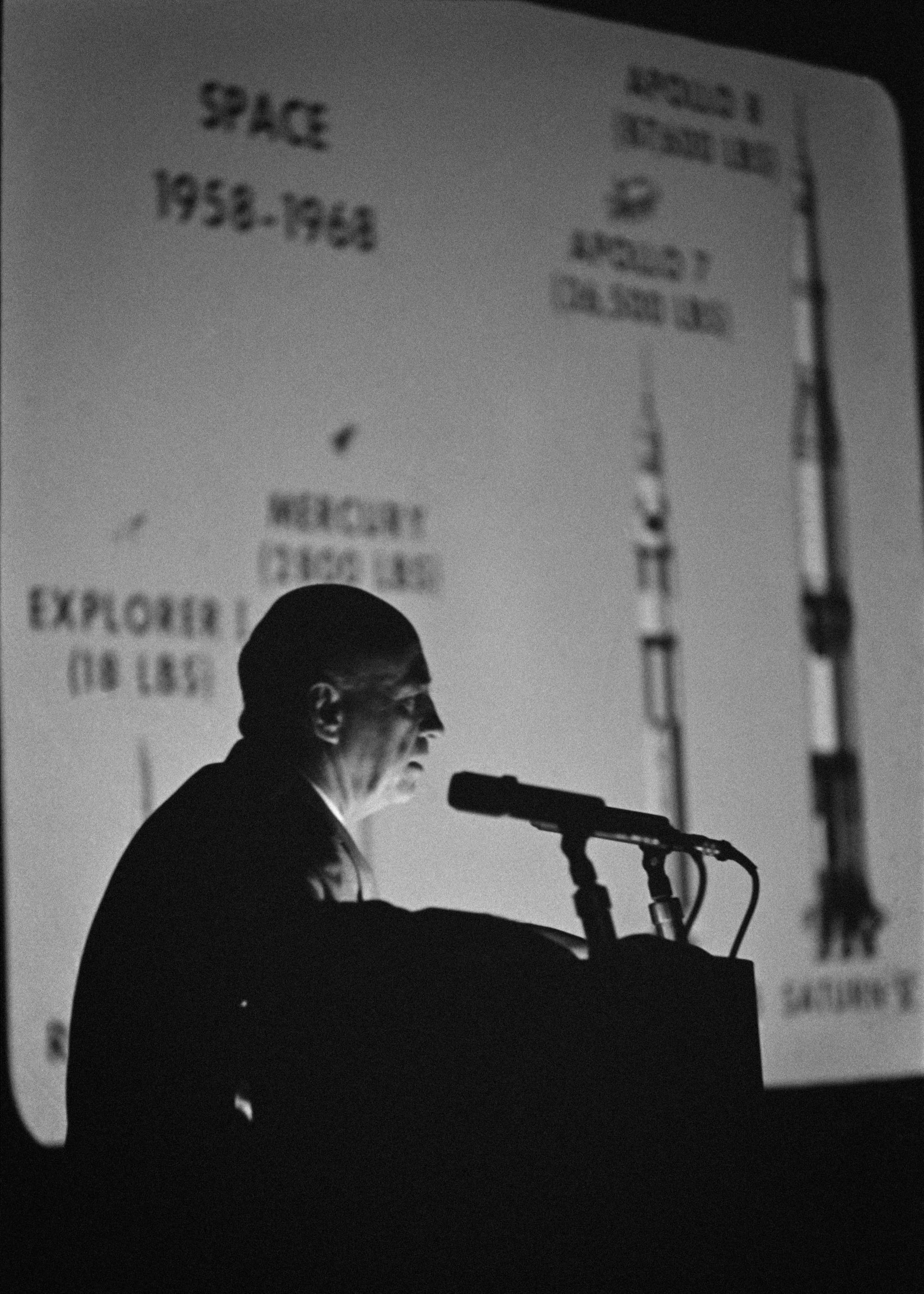

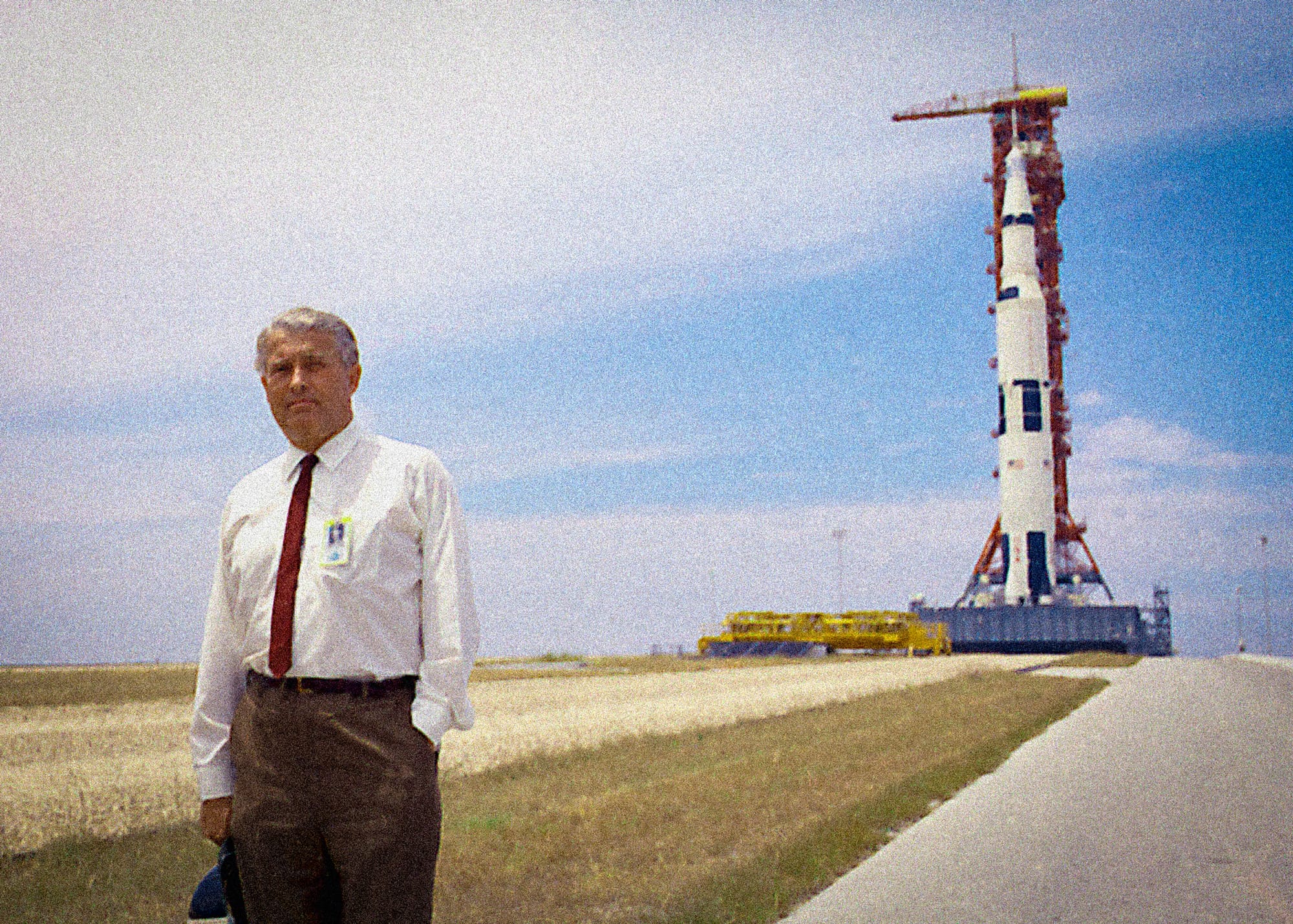

1 July 1969 – Dr Wernher von Braun in front of the Saturn V rocket

Wernher von Braun is a key but complex figure in the Apollo story. A former Nazi party member who worked on guided missiles for the Germans throughout the Second World War, he was centrally involved in the development of the V-2 rocket.

After his surrender to the US army in 1945, von Braun and his team of engineers was brought across the Atlantic. They moved from White Sands, Mexico, to Huntsville, Alabama, where they were able to continue their research. In 1960 von Braun was employed by the newly-formed NASA at the Marshall Space Flight Center where he worked on the development of the Saturn rocket.

Von Braun would later be described as 'the only non-astronaut in the space program who became a household name'. He was 'movie-star handsome, with an expansive smile and European charm'. Among some, however, the taint of his Nazi past still lingered.

This photograph of von Braun in front of the Saturn V rocket at the start of July 1969 links the Apollo story with a deeper, more disturbing history.

27/91

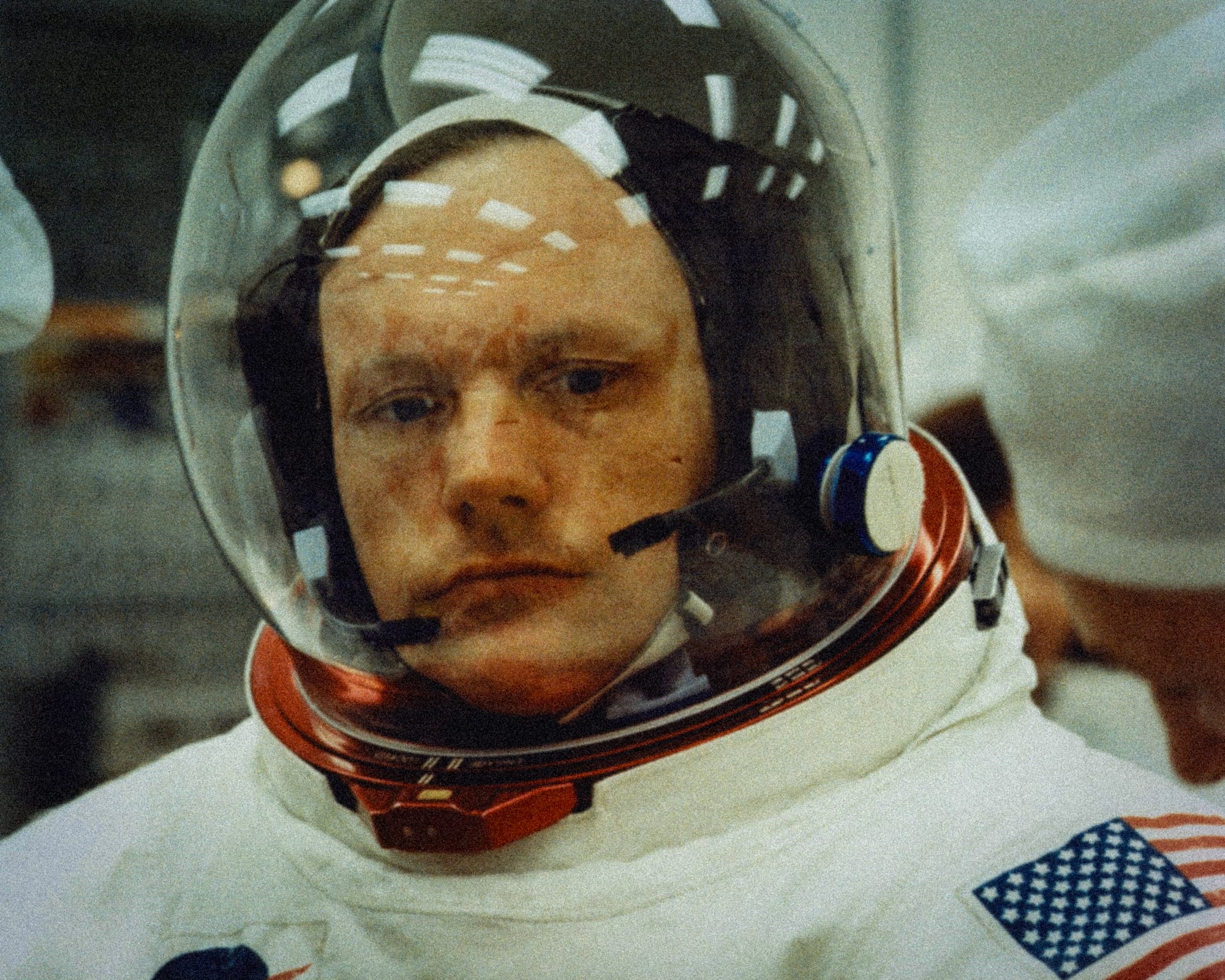

1 July 1969 – Neil Armstrong testing his spacesuit

The early weeks of July were crammed full of tests. Newspapers relayed the daily state of affairs at Florida as technicians swarmed over the Saturn rocket, ensuring that every bolt was tight and all components functioned correctly.

Meanwhile Armstrong, Collins and Aldrin worked ten hours a day, six days a week on their personal preparations for the launch. One essential task was to ensure that they felt comfortable in their space suits. Like everything in the Apollo Program, these had been made specially made, with parts of them produced by seamstresses at the Playtex sewing floor in Delaware.

Armstrong, pictured above, can be forgiven the look of apprehension. On 5 July the astronauts would come to the end of their training phase. Shortly after they would be transferred to the Cape in readiness for the launch.

28/91

7 July 1969 – Stars and Stripes

While the focus remained on the astronauts, the beginning of July was an exhausting time for hundreds of others too.

This photograph shows the NASA engineer Jack Kinzler (right) preparing the US flag kit for Apollo 11. As well as the flag, Kinzler was also responsible for preparing a plaque that would be left on the Moon.

Collins would later state that the signature the plaque bore was not his, but one produced by some machine in Houston.

29-30/91

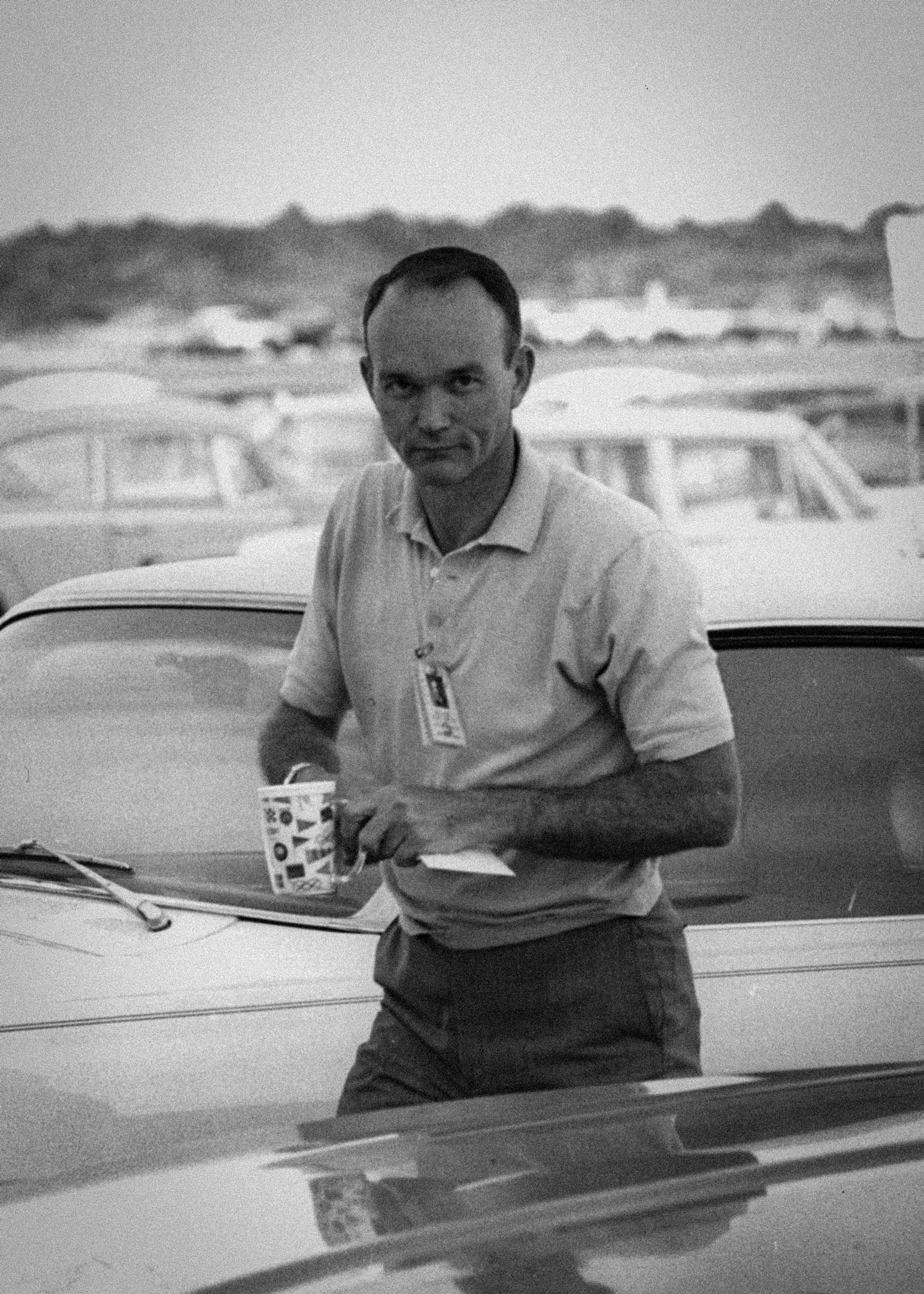

9 July 1969 – Turning up to work

A week before launch Collins was captured by photographers in two very different contexts. The first showed him as a regular guy, turning up to work with his coffee. The second framed the unique nature of his profession: forced back in his chair in his full space kit.

Throughout this bewildering time, Collins drew strength from his training and the institutional emphasis on process. In the six months between January and July he calculated that he had spent more than four hundred hours in the simulator.

Collins was sure that this experience would serve him well. 'With all that complicated gear up there for eight days,' he reasoned, 'something had to break'.

31/91

9 July 1969 – Practice in the Lunar Module

All three of the astronauts had very different responsibilities on the mission. While Collins would remain in lunar orbit, the task of piloting the lunar module fell to Armstrong.

In this photograph Armstrong can be seen approaching a helicopter, which he used to simulate landing on the Moon.

32/91

9 July 1969 – More drills

For the astronauts, the checklists and run-throughs seemed endless. All of them, though, understood how important they were. As Collins later wrote:

Consider someone who has never ridden in a car before. Without actually letting him drive, prepare him for a trip across Los Angeles, from Downey down the Long Beach Freeway, then up the San Diego Freeway to the airport.

Along the way, let him have a high speed blowout, change the tire, and proceed. Explain to him the rules of the road, the operation of the machinery, the physical condition of the clutch, brake, and gas, the feel of the wheel. Condition him to red lights, flashing ambers, the glare of oncoming brights.

Trust him to make that trip the first time, by himself, without dinging a fender. Far-fetched perhaps, but that is how we did it on Apollo.

33/91

11 July 1969 – A silicon disc

Along with the flag, the plaque and the olive branch, a one-and-a-half-inch silicon disc was stowed into the astronaut's luggage. It contained miniature messages from seventy-three heads of state as a concession to multilateralism.

At one point during preparations the management at NASA discussed the possibility of transporting a flag for every UN member nation. A design was even conceived that looked a little like a fold-open Christmas tree that would display all the various flags in a 'colourful cone'.

When members of the US Congress reacted with horror to news of this, the idea was quietly dropped.

34/91

14 July 1969 – Cooks at the astronaut quarters of the NASA Kennedy Space Center (KSC) preparing food for the astronauts

In the last few days before the launch, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins were moved into the crew quarters. Once inside very few people could reach them and they were left in peace to contemplate the days ahead.

One of those who came into close contact with the astronauts during this time was Lew Hartzell, the cook. Hartzell was a colourful character who had spent many years as a cook on tugboats and yachts. His work had brought him into contact with several celebrity characters and Collins remembered that he 'recounted good stories' of them 'falling overboard and other excitements'.

35/91

15 July 1969 – Last supper

The evening before the launch the astronauts sat down for a final terrestrial dinner. Relations between the trio had always been cordial and Armstrong's broad smile gives a hint of conviviality.

Collins had detected a hint of jealousy in Aldrin though. His 'basic beef' he would later state, 'was that Neil was going to be the first to set foot on the Moon'. Way back in the early spring, when the flight plans were being worked through, there had been some check lists that had Aldrin making the initial descent down the ladder. Armstrong had ignored these and 'exercised his commander's prerogative to crawl out first'.

'Buzz’s attitude took a noticeable turn in the direction of gloom and introspection shortly thereafter', Collins noticed.

'Once he tentatively approached me about the injustice of the situation but I quickly turned him off. I had enough problems without getting into the middle of that one.'

36/91

15 July 1969 – The three quiet Americans cut the small talk

The final press conference had a curious atmosphere. Great excitement was building about the launch and what might follow afterwards, but the astronauts did not give any headline answers to the questions. 'Totally banal, both questions and answers', was one verdict.

By this time all three had received their final medical checks and had entered the final phase of preparations for launch •

This Viewfinder feature was originally published July 16, 2024.

More

The Summer of 69 (Part 2 of 2)

The Moon landings gave the summer of 1969 its defining story. But elsewhere in the world many other events of consequence were playing out

References

This essay has been compiled from many sources. Chief among them are Michael Collins's memoir, Carrying the Fire, Charles Murray and Catherine Cox's Race to the Moon and the contemporary newspapers.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store