The Summer of 69 (Part 2 of 2)

The Moon landings gave the summer of 1969 its defining story. But elsewhere in the world many other events of consequence were playing out

The summer of 1969 brought the most thrilling journey in the history of humankind. That July the astronauts of the Apollo 11 mission realised President John F. Kennedy's ambition of landing on the Moon and returning safely to Earth.

In this photographic essay, we follow the story through the anxious weeks of preparation, towards the landings and onto the crowning moment of triumph, on 24 July, when the returning astronauts splashed down safely in the Pacific.

The Moon landings gave the summer of 1969 its defining story. But elsewhere in the world many other events of consequence were playing out.

Looking back at these stories, fifty-five years later, we can glimpse a vivid moment in human history when culture, politics and science were all charged with a powerful, restless energy.

Words by Peter Moore

With curated and remastered images from the public archives by Jordan Acosta

37-38/91

16 July 1969 – Early morning sunshine

As the astronauts ate Lew Hartzell's breakfast of eggs, toast, juice and coffee, a great mass of people began to assemble within sight of launchpad 39A at Cape Canaveral in Florida.

Over the past few months Apollo launches had become an almost familiar sight, with one every three months or so. But although the scene looked curiously like the others that had gone before, and people knew what to expect, the mood was changed. 'This time it is different', wrote one journalist. 'For this, at last is the big one — the run to the Moon itself.'

In the first sunlit hours of 16 July 1969 a million people were estimated to have assembled at Cape Kennedy. Another 500,000,000 more were reportedly watching their television sets.

'The desire [was] to see for themselves, to be in on the event that should put 1969 into the history books for all time.'

39/91

16 July 1969 – Pad A. Launch Complex 39

For Collins, carrying his oxygen container to the launch pad felt rather like hauling a suitcase. After the transfer van and elevator ride up the rocket, he was struck by a vivid thought:

‘This elevator ride, this first vertical nudge, has marked the beginning of Apollo 11, for we cannot touch the Earth any longer. I am treated to one more view, however, one last bit of schizophrenia as I stand on a narrow walkway 320 feet up, ready to board Columbia.

On my left is an unimpeded view of the beach below, unmarred by human totems; on my right the most colossal pile of machinery ever assembled.

If I cover my right eye, I see the Florida of Ponce de Leon, and beyond it the sea which is mother to us all. I am the original man. If I cover my left eye, I see civilization and technology and the United States of America and a frightening array of wires and metal.’

40/91

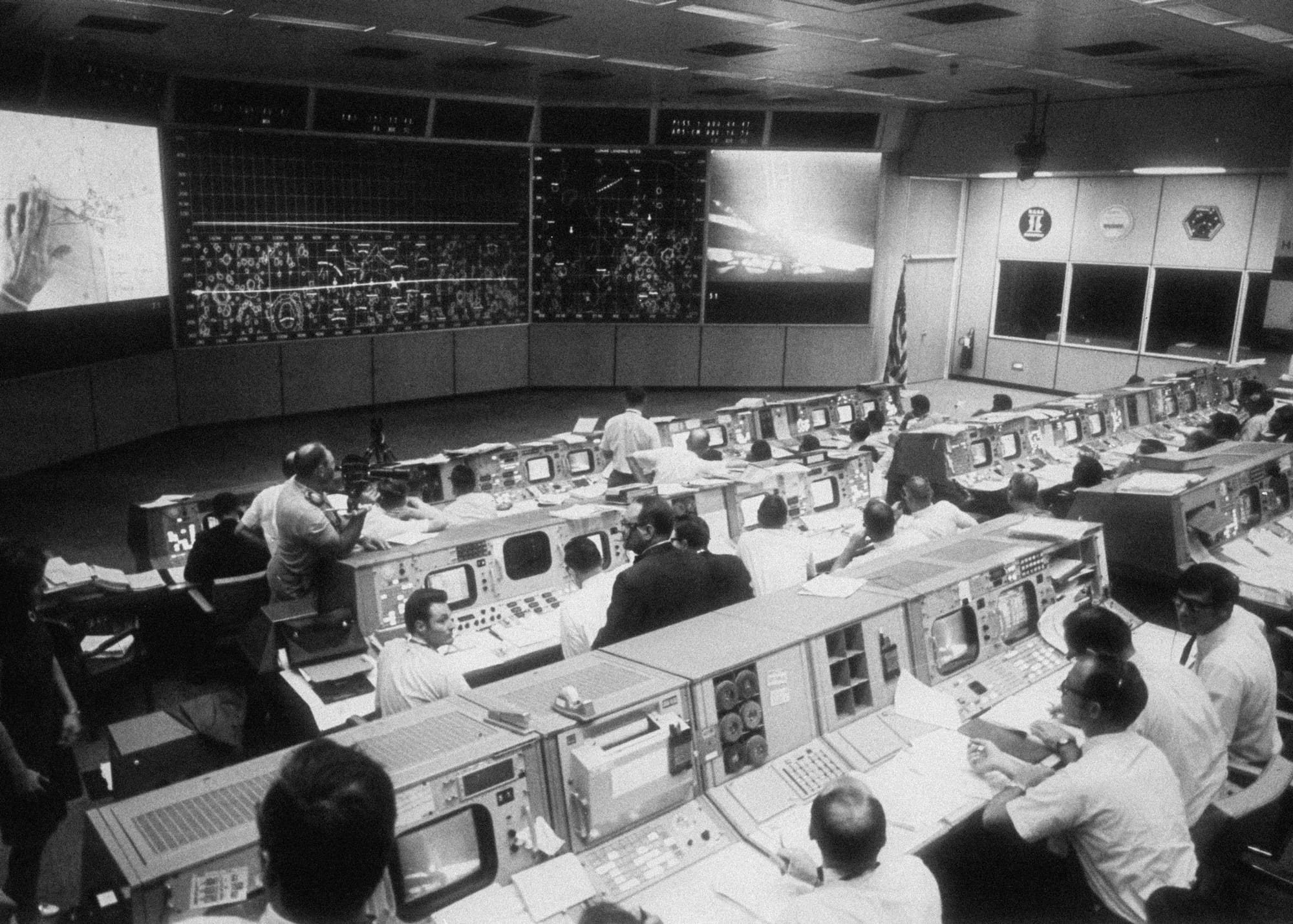

16 July 1969 – Inside the Control Center

With the audience so huge and the ambition so bold, the pressure inside the control room reached its maximum pitch.

Over the past decade the US government had spent something in the region of £10,000,000,000 to reach this point, in the hope of realising Kennedy's ambition. Any small factor, any piece of bad luck, could result in both catastrophe and embarrassment on an unprecedented scale.

The consequent sense of tension and concentration is embedded in this photograph. Everyone in the room knew how hazardous a moment launch was, with mammoth engines, combustible fuels, searing temperatures and destructive wind blasts.

It would take eleven minutes for Apollo 11 to reach the stability of orbit.

Despite the risks a Greek insurance company had agreed to cover the astronauts against loss. 'But they won't pay out', one paper playfully remarked, 'if the men are kidnapped in Space. Or if they like the Moon so much that they refuse to return'.

41/91

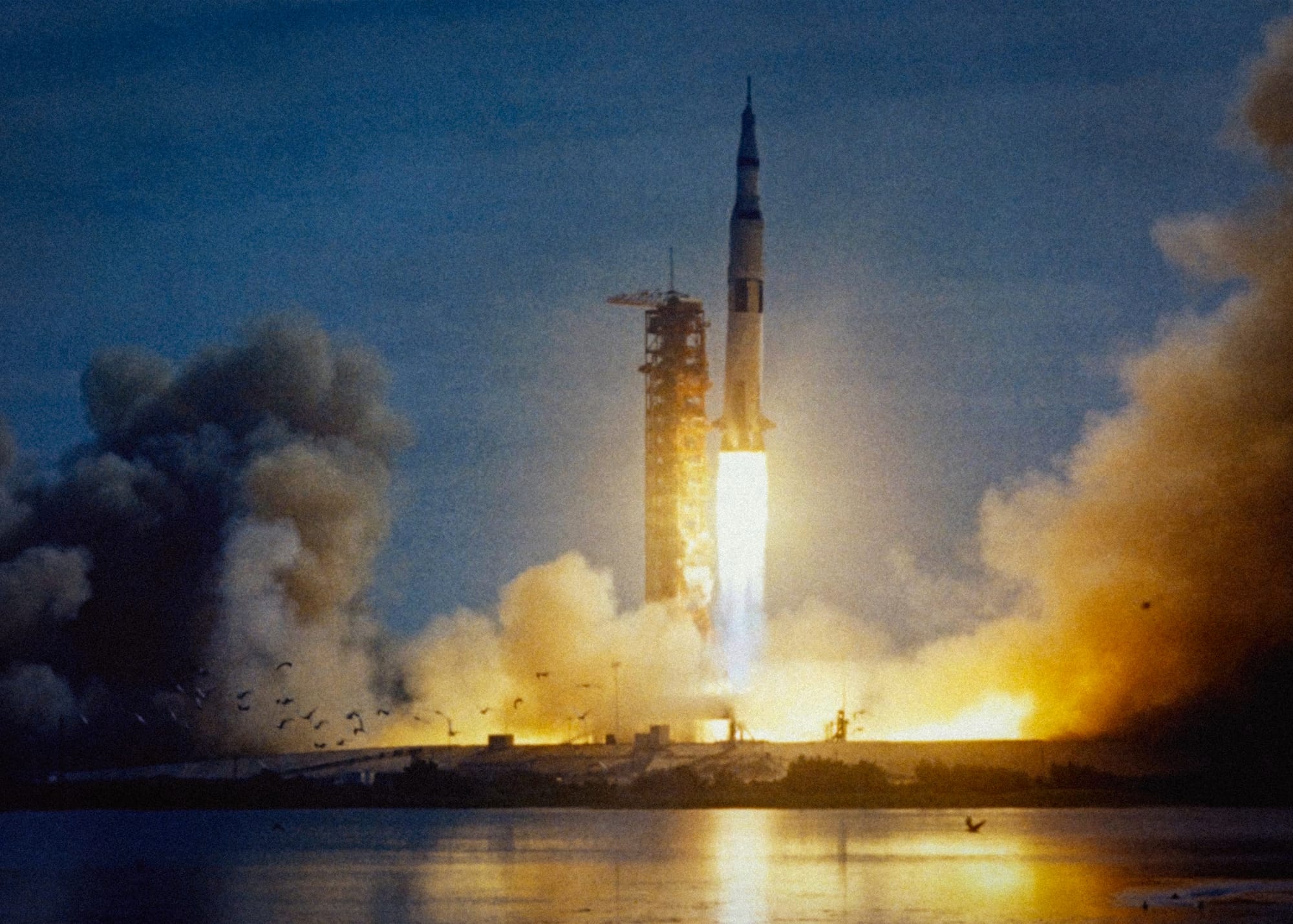

16 July 1969 – 'Shake, rattle and roll'

For the launch Aldrin sat in the centre of the three seats, with Armstrong on his left and Collins to his right. Each of them knew that during the first 150 seconds of flight four and a half million pounds of fuel would be burnt, propelling them to a speed of 9,000 feet per second.

‘Here I am, a white man', wrote Collins, 'age thirty-eight, height 5 feet 11 inches, weight 165 pounds, salary $17,000 per annum, resident of a Texas suburb, with black spots on my roses, state of mind unsettled, about to be shot off to the Moon. Yes, to the Moon.’

42-43/91

16 July 1969 – Streaking far out into space

As the 'teeming bird life of the flat Florida coastlands was scattered in fright', the Saturn V rocket vanished into the sky. For all those left on the ground, there was a sense of wonder at the coolness of the astronauts.

'There was scant small-talk to excite an enthralled world. The tough, self-assured pioneers confined themselves to drawing laconic radio responses like ‘Roger’ and ‘Thank you'', wrote one journalist.

'Even their heartbeats were proof of their extraordinary calm. Doctors monitoring their pulse rates by radio reported that they rose only slightly at blast off.'

Armstrong's – 110 beats per minute

Collins's – 99 beats per minute

Aldrin's – 88 beats per minute

44-45/91

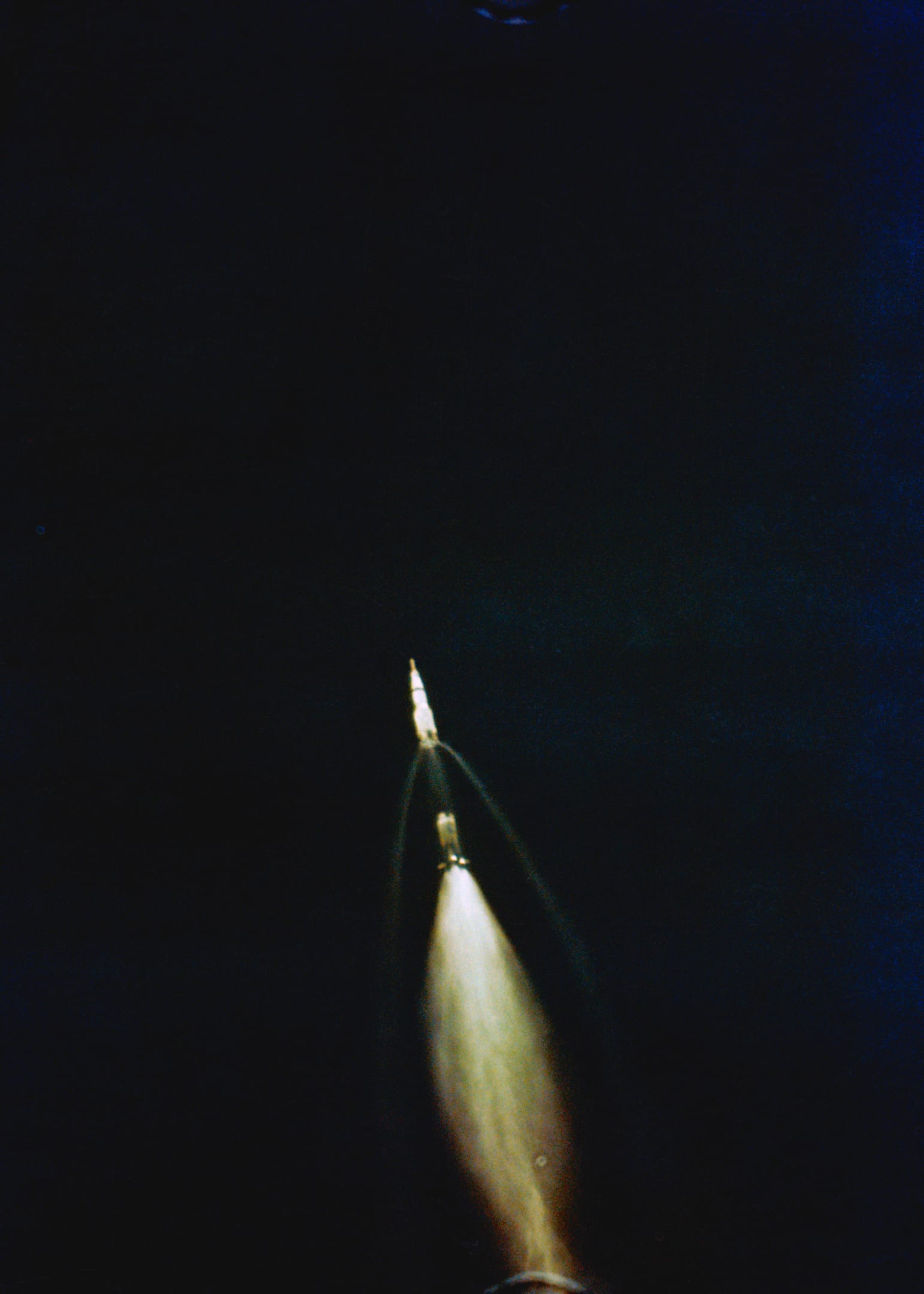

16 July 1969 – Into Orbit

As Apollo 11 arced into the stratosphere, a 70mm tracking camera, mounted on an aircraft, captured this final view of the rocket (left).

Just eleven minutes after launch, it had left Earth's atmosphere and was in orbit at speeds of around 17,500 miles-per-hour.

46/91

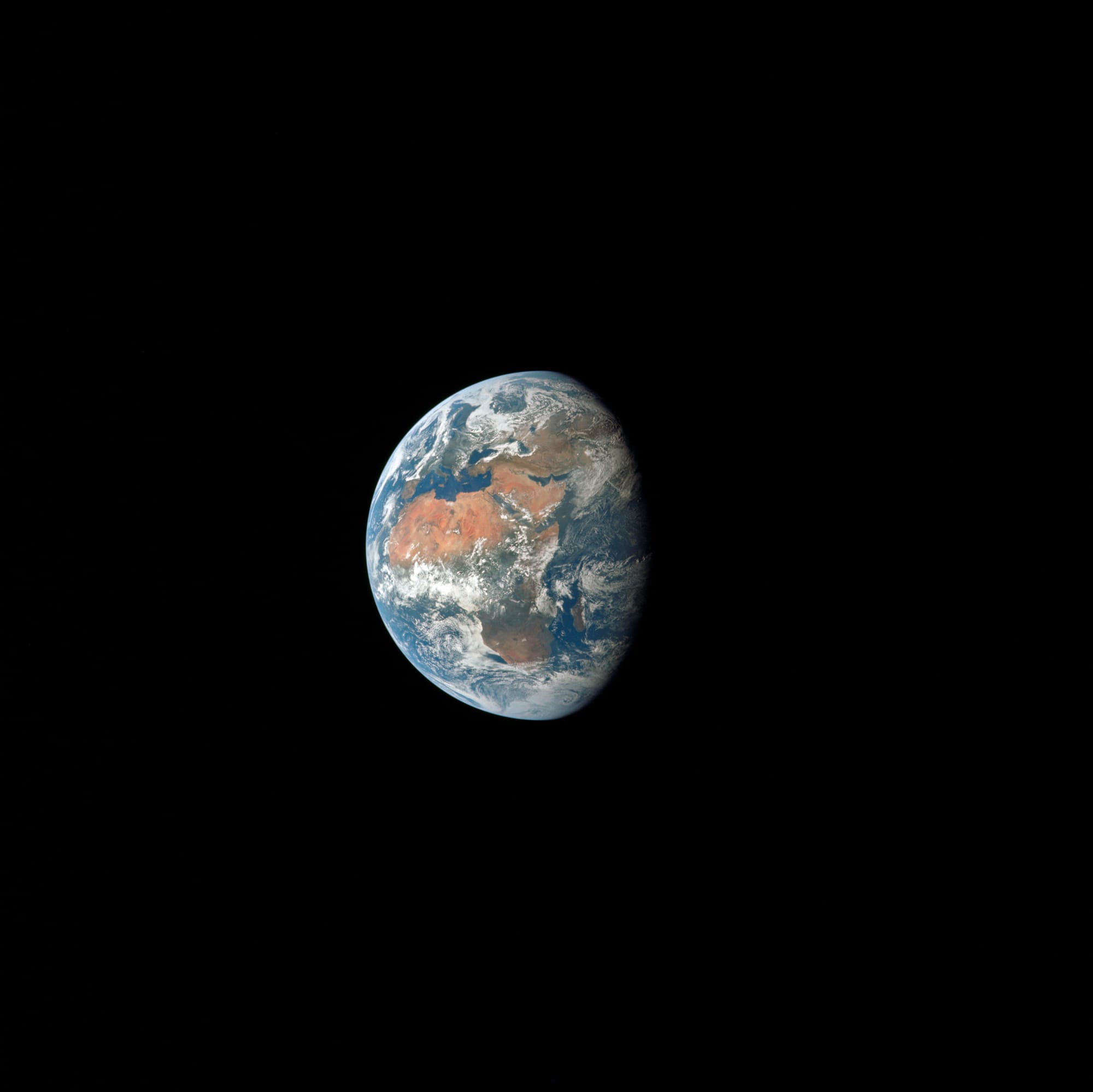

17 July 1969 – Blue Planet

The night before the launch, Collins had read over a poem that his wife had sent him. It was titled, To a Husband Who Must Seek the Stars.

On 17 July Collins was among the stars. But rather than looking towards them, he found himself frequently glancing back at the planet that he was leaving behind. This spectacular photograph, taken during the journey to the Moon, shows parts of Africa and Europe.

The astronauts were struck by the vivid nature of the colours Earth emitted. The blues of the oceans, greens of the forests and whites of the clouds contrasted strongly with the blackness of space.

Unseen Histories Archive / NASA

47-48/91

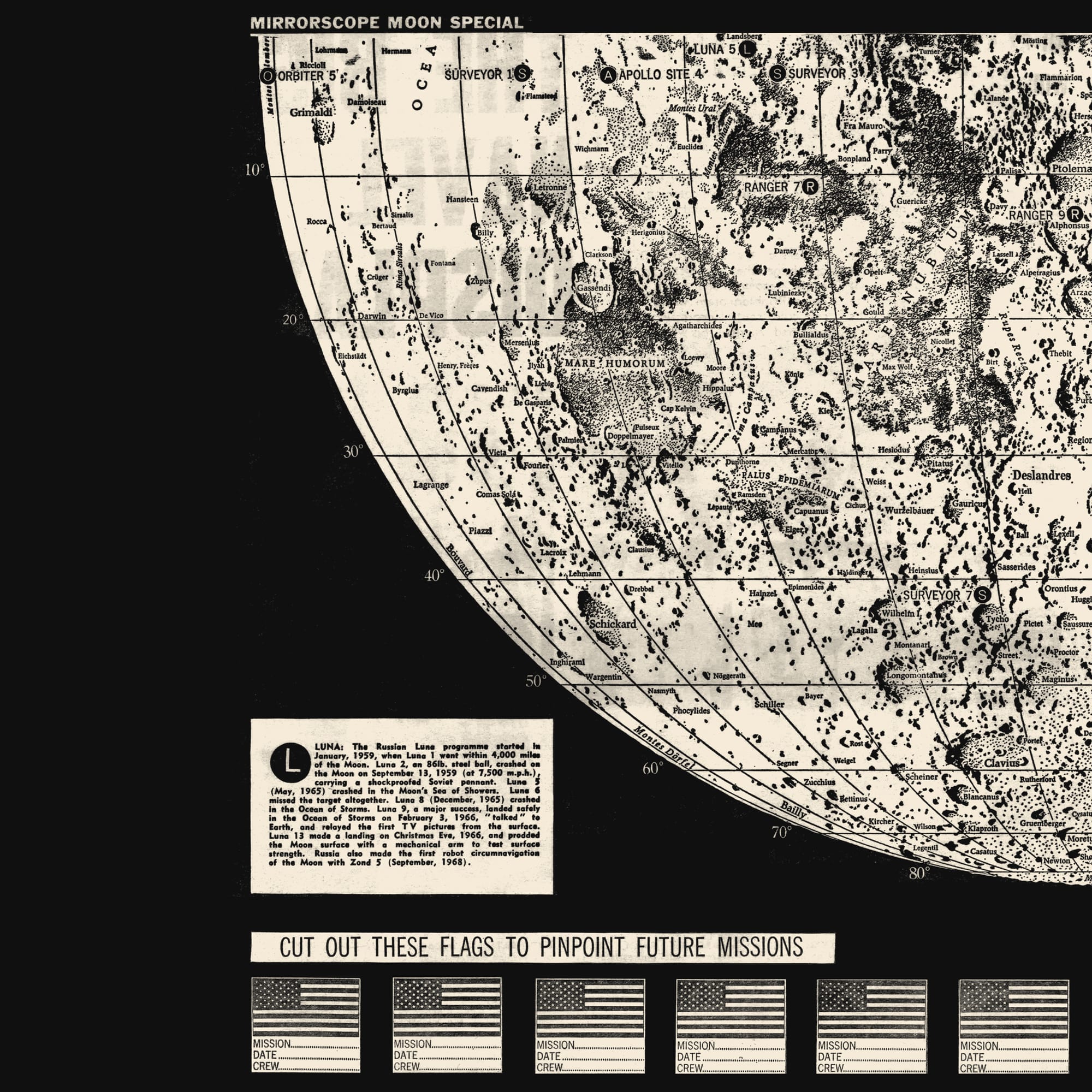

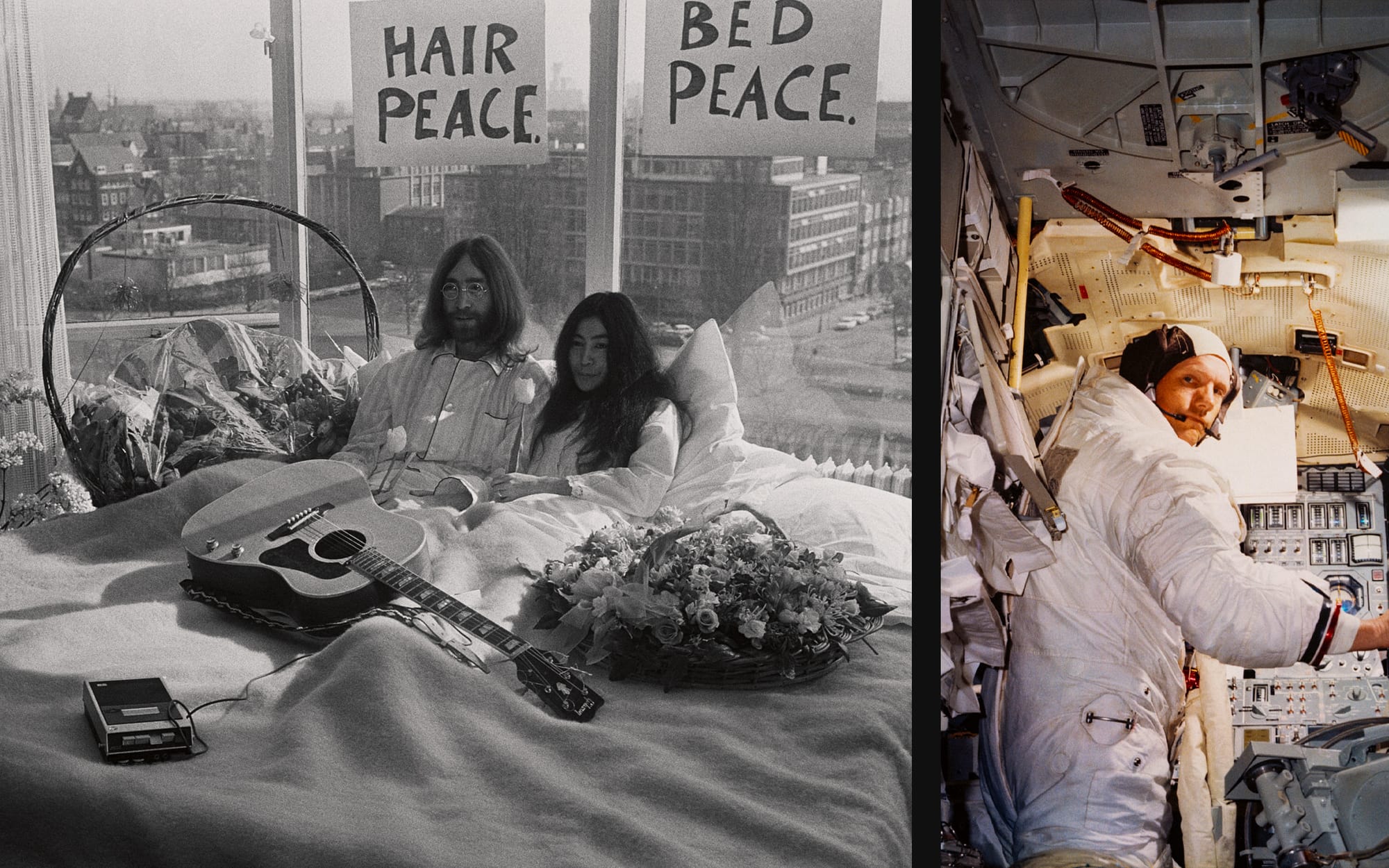

19 July 1969 – Space Fever

As the astronauts looked back at Planet Earth, millions of people spent the days following 16 July gazing up at the night sky. The Apollo mission had catalysed a new interest in science and astronomy. The diagram on the left is typical of the pieces that ran in newspapers throughout this week.

Hoping to catch hold of a commercial opportunity, in the UK Penguin Books announced on 19 July that their author Peter Ryan – 'closely associated with the BBC Apollo team' – was well advanced with a manuscript entitled Invasion of the Moon: the Story of Apollo 11.

Replete with four colour photographs of Neil Armstrong standing on the Moon (something which was yet to happen) and 16 pages of black and white images, the book was set to be published on 10 August, 'the first book available on the Apollo 11 flight'.

49-50/91

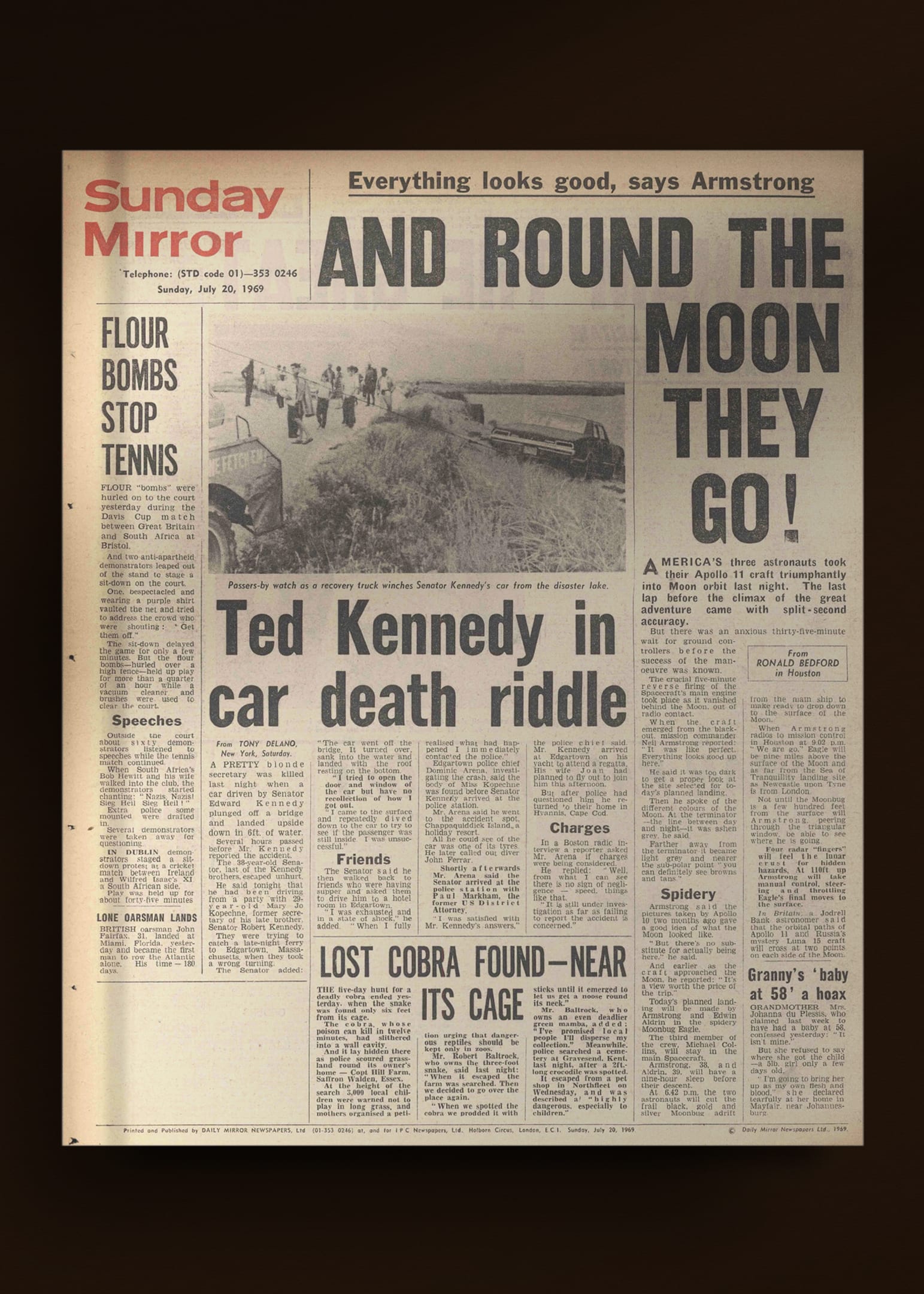

19 July 1969 – Ted Kennedy in car death ride

While attention was mainly consumed by Apollo 11's progress, one other major story did break during the rocket's journey to the Moon.

This was a bleak report concerning another of the Kennedy brothers. Senator Edward Kennedy (above), the sole surviving son of Joe Kennedy had been involved in a strange, tragic incident near Edgartown in Massachusetts.

Articles told how Kennedy's car had swerved off a road and plunged into water. His passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne (29), a former secretary of his late brother Robert, had been drowned.

51/91

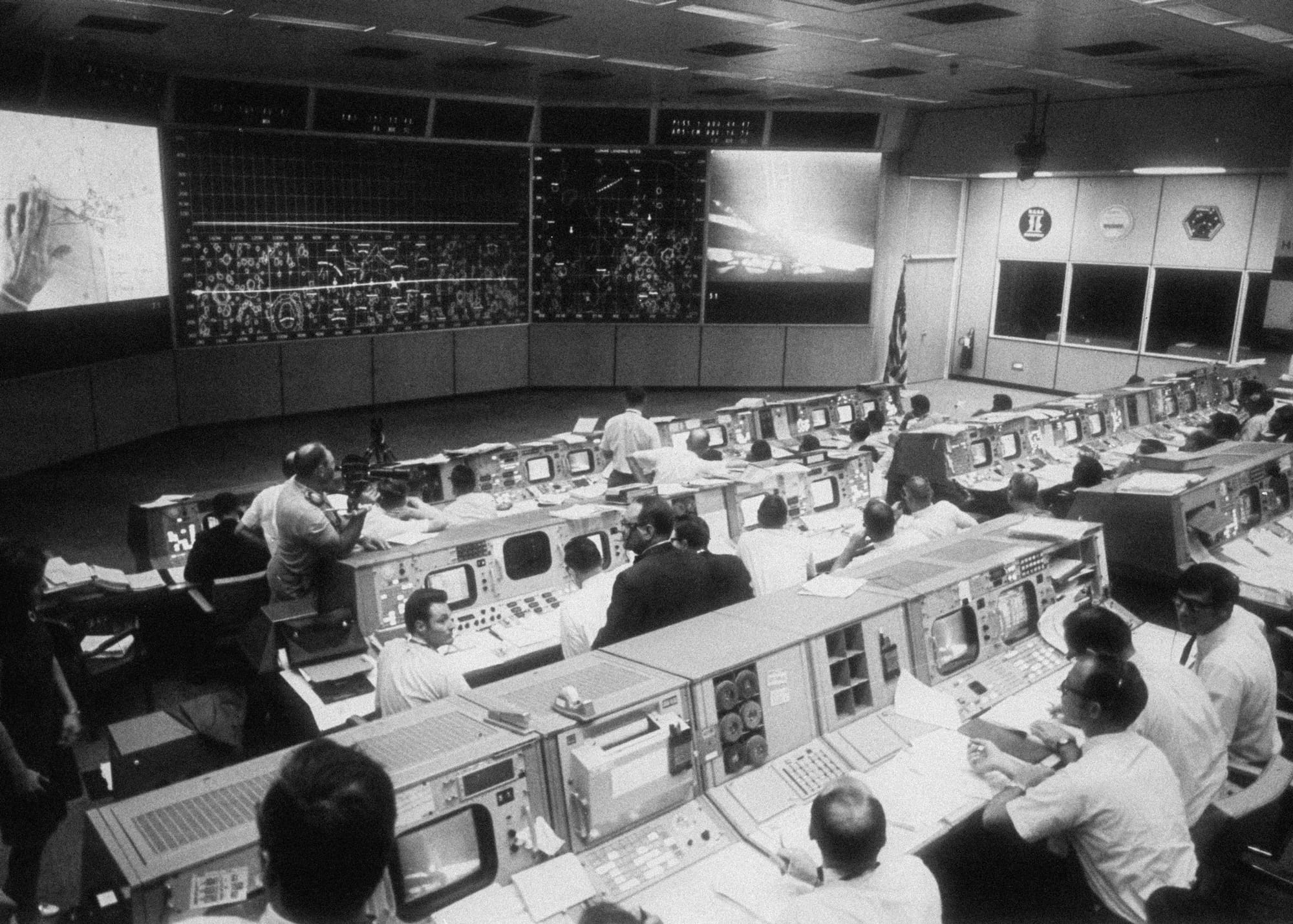

20 July 1969 – Inside Mission Control

A evocative vignette is told about Eugene Kranz on the day of the Moon landings. There is no tape recording of this episode, but it is said that Kranz sealed off the control room from all prying eyes and ears. Then he addressed those around him.

The story is related in Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox's book, Race to the Moon:

'Hey gang, we're really gonna go and land on the moon today. This is no bullshit, we're going to go land on the moon. We're about to do something that no one has ever done.

Be aware that there's a lot of stuff that we don't know about the environment that we're ready to walk into, but be aware that I trust you implicitly. But also I'm aware that we're all human. So somewhere along the line, if we have a problem, be aware that I'm here to take the heat for you. I know that we're working in an area of the unknown that has high risk.

But we don't even think of tying this game, we think only to win, and I know you guys, if you've even got a few seconds to work your problem, we're gonna win. So let's go have at it, gang, and I'm gonna be taggin' up to you just like we did in the training runs, and forget all the people out there. What we're about to do now, it's just like we do it in training. And after we finish this sonofagun, we're gonna go out and have a beer and we'll say, 'Dammit, we really did something.'

52/91

July 1969 – Dr. Robert R. Gilruth keeps up with progress

Another of those at Mission Control on 20 July was Robert Gilruth, the Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), who had overseen the beginning stages of the Apollo program.

53/91

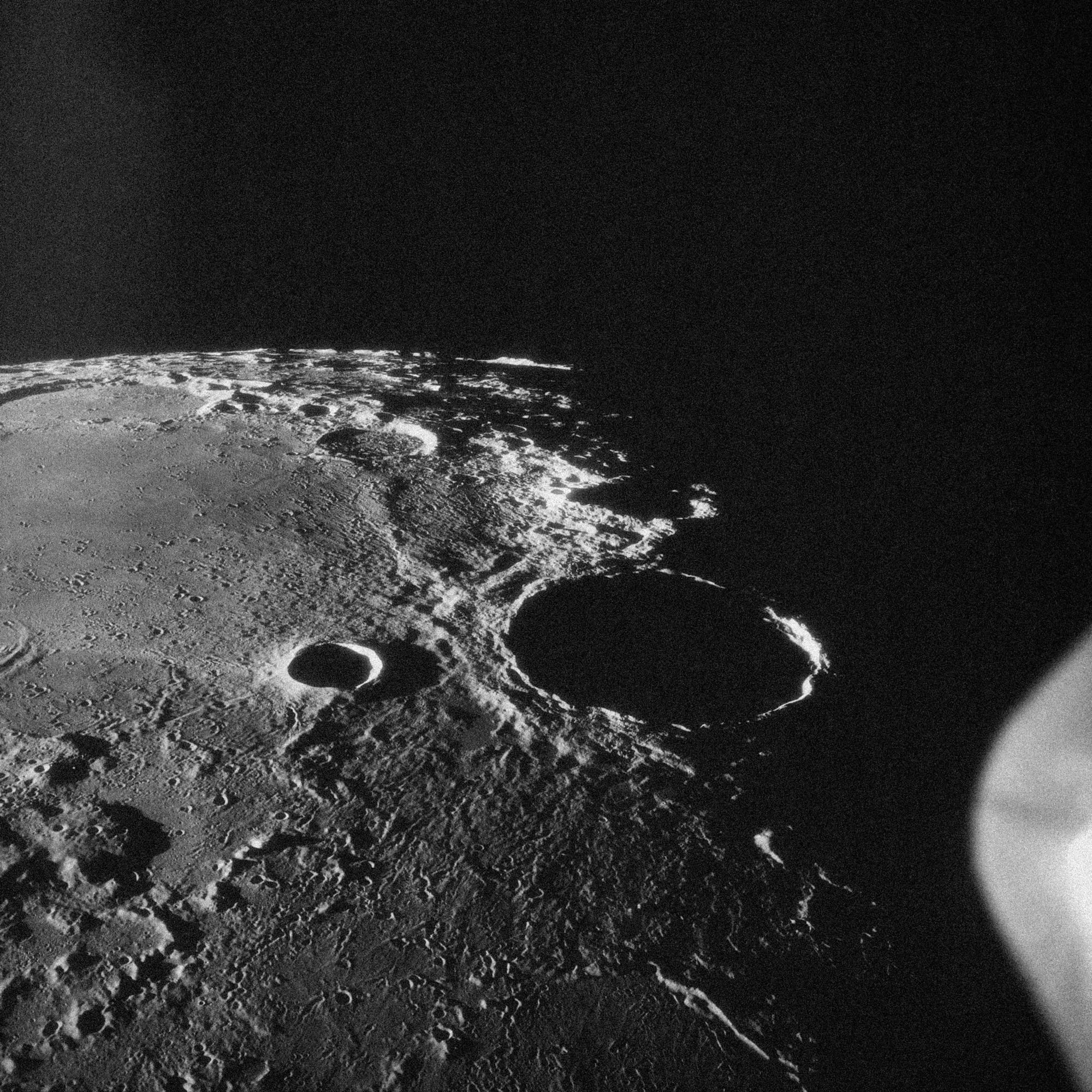

20 July 1969 – A view of the crater Theophilus located at the northwest edge of the Sea of Nectar on the lunar nearside

Onboard Apollo 11, Collins was left to marvel at the ingenuity that had brought the three of them to the Moon with such precision. They had travelled nearly a quarter of a million miles from Earth and arrived with pinpoint accuracy at the Moon, which, on top of everything else, was a 'moving target'.

There was now the separate question of the Moon's colour to consider. The previous missions had generated some discussion about its true colour. To Apollo 8 it was a simple black, white and grey. For those on Apollo 10 there was a more subtle palette of browns and light tans.

Apollo 11 'discovered a bit of truth on either side of the argument' with the more intricate shades appearing at different moment of the lunar day. Gazing down at noon, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins saw 'a cheery rose colour, darkening towards brown on its way to black night'.

54/91

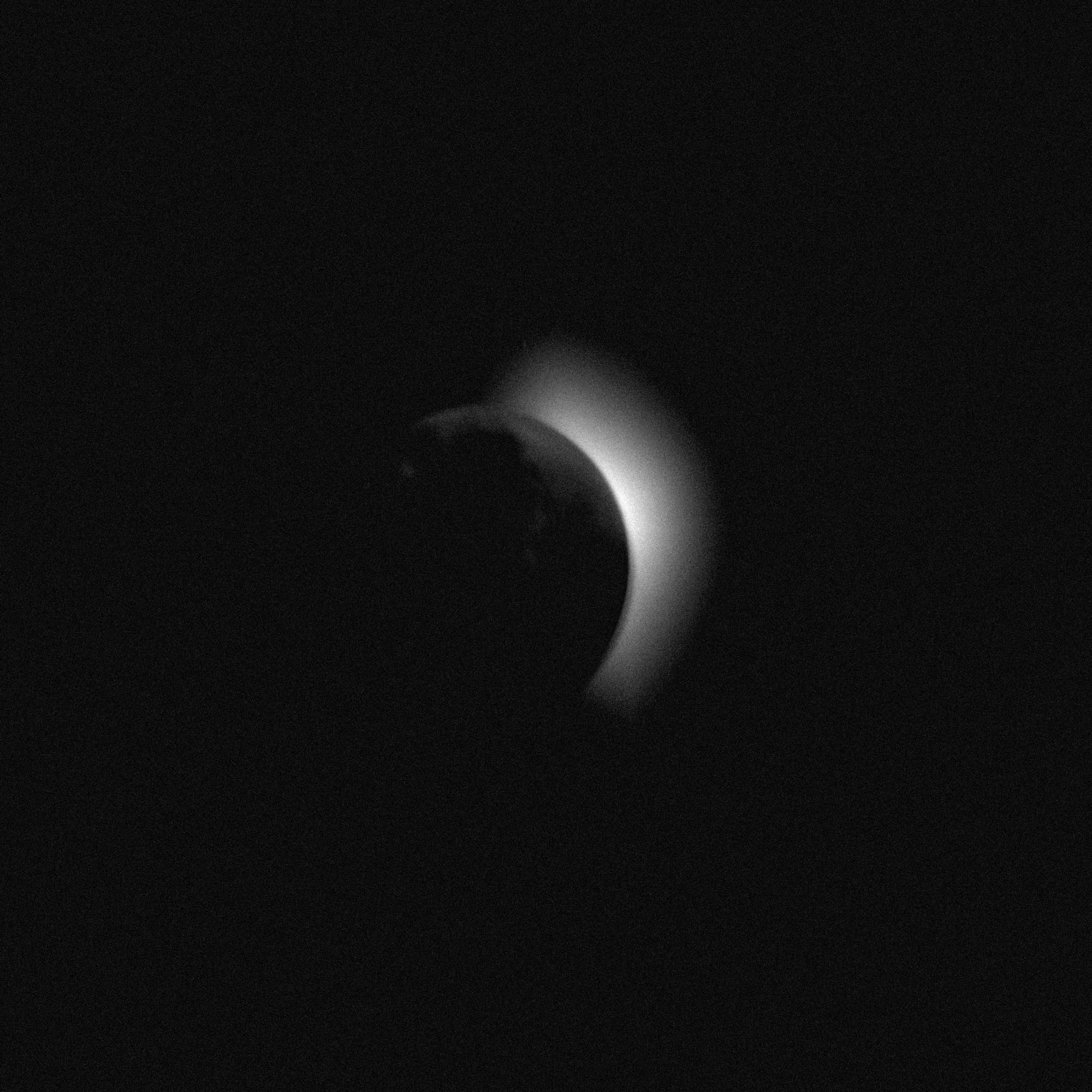

20 July 1969 – Earthrise

Once in lunar orbit, the astronauts were confronted with an entirely new sight. The Earth would vanish and reappear as they progressed on their circular course. Always the most welcome and exciting moment was when the Earth hove back into view again.

'It pokes its little blue bonnet up over the craggy rum and then, not having been shot at, surges up over the horizon with a rush of unexpected colour and motion'.

55/91

20 July 1969 – The far side of the Moon

Another important part of Apollo 11's empirical observations was studying the appearance of the mysterious far side of the Moon. This photograph shows this little known area, 'in the vicinity of creator number 308', and it reveals a harsh, pock-marked landscape — one that has suffered the bombardment of millions of years of meteorite strikes.

56-57/91

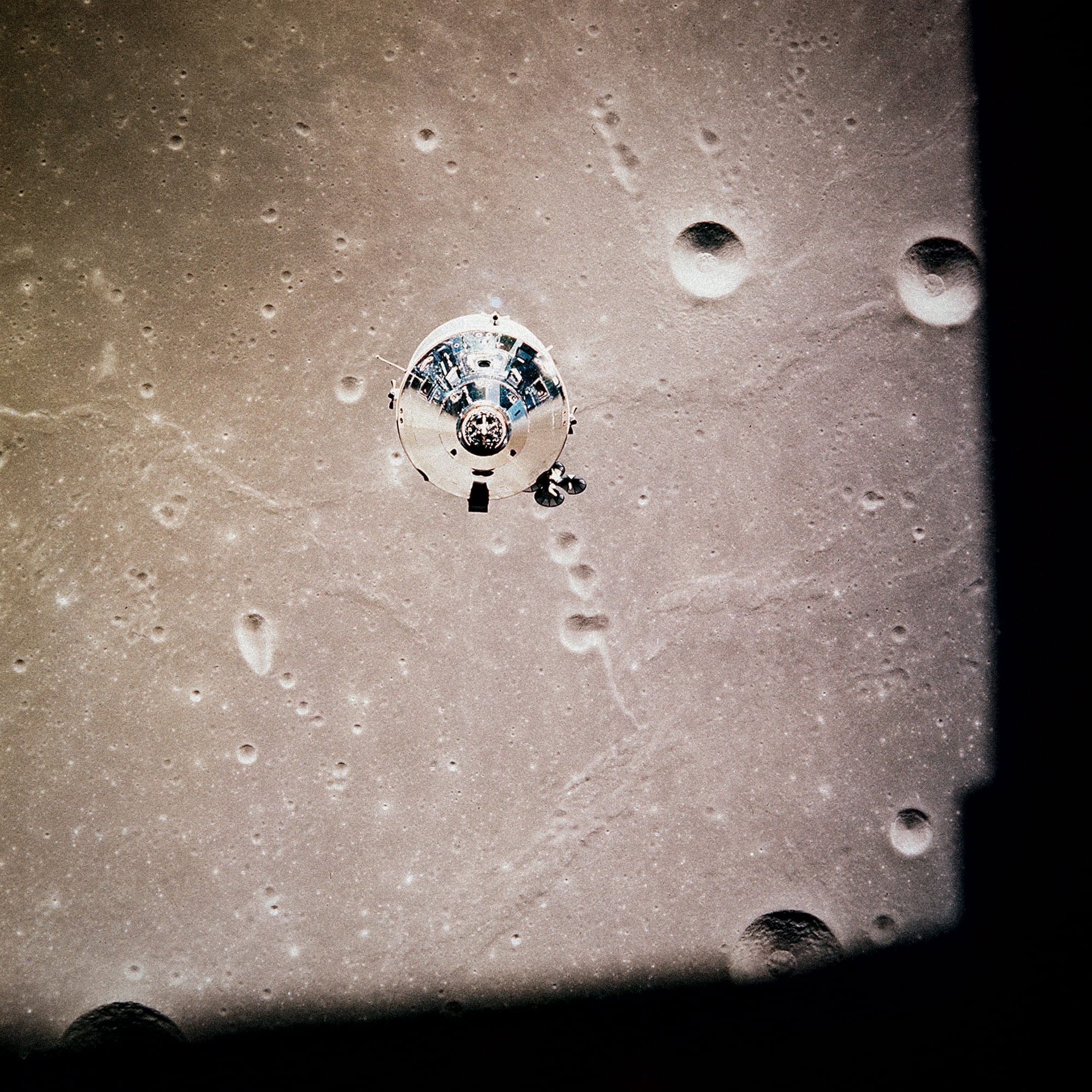

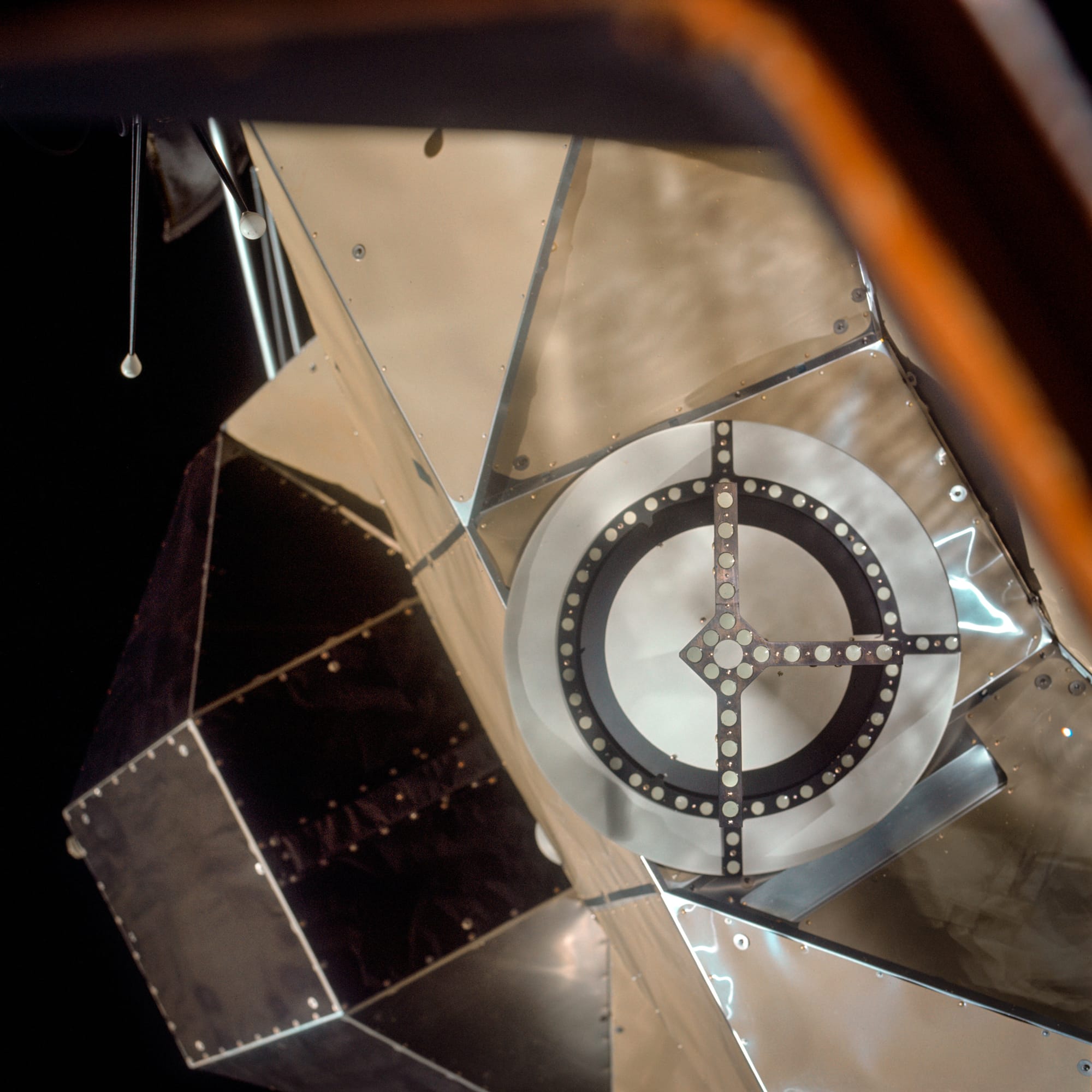

20 July 1969 – Descent

Once settled in lunar orbit, the crew were guided through a series of manoeuvres by Mission Control. Importantly the engines needed to be fired to reduce speed. This procedure took place behind the Moon while the astronauts were out of radio contact.

'A great stillness descended on the Houston mission control during the 45 minutes the spacecraft was on the other side', it was reported. But each part of the sequence was performed successfully.

The photographs above show the final preparatory phase when the command and service module has detached from the lunar module and the descent is poised to begin.

58/91

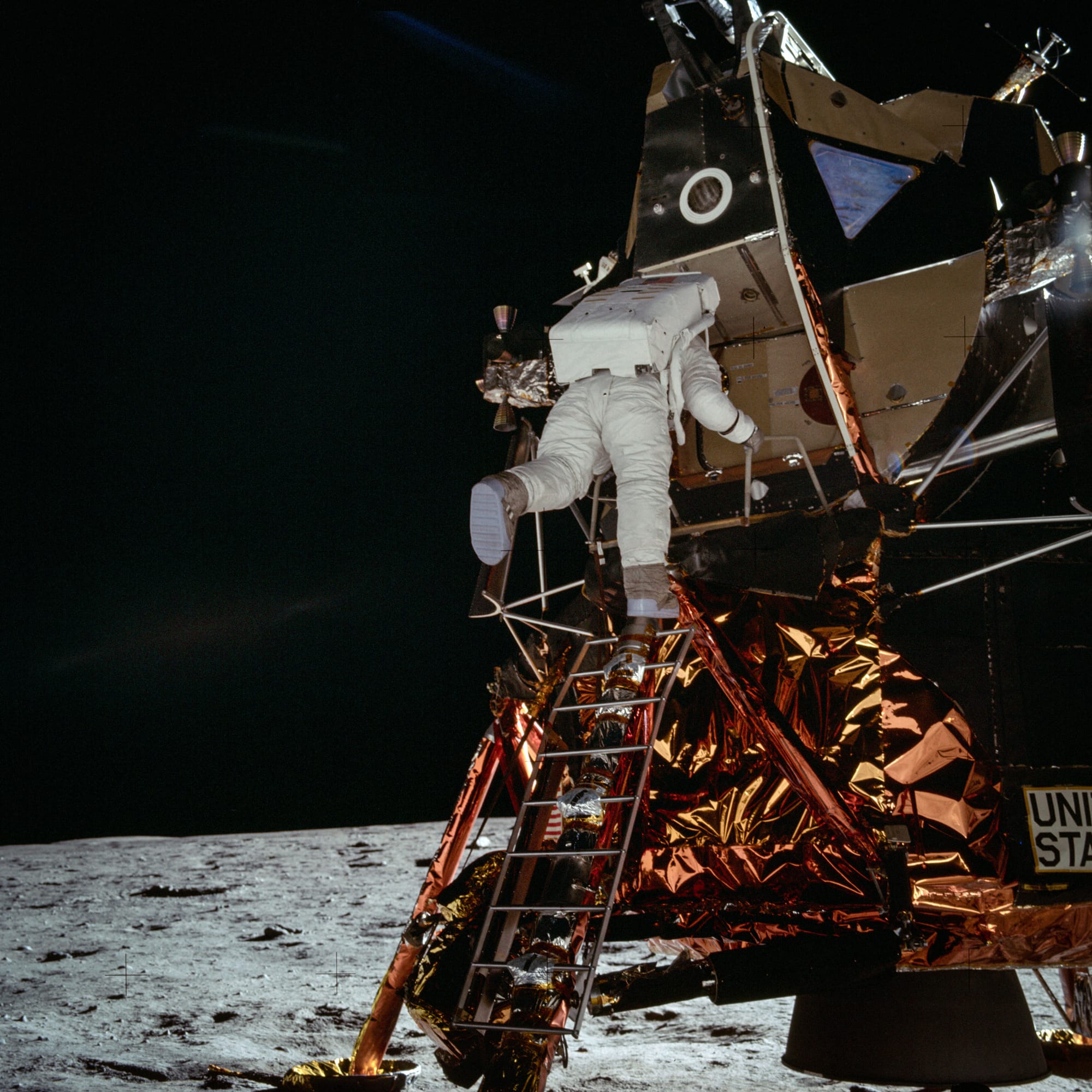

20:17 hrs, 20 July 1969 – 'One small step for man'

Neil Armstrong brought the lunar module, which had been given the name 'Eagle', down to the surface of the Moon with about thirty seconds of fuel left in the tank.

There followed one of the most watched and memorable scenes in human history, as Armstrong gingerly worked his way down the rungs of the ladder, describing his surroundings and sensations as he went.

At 20:17 GMT, Armstrong hopped off onto the Moon's surface. 'That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind'.

59/91

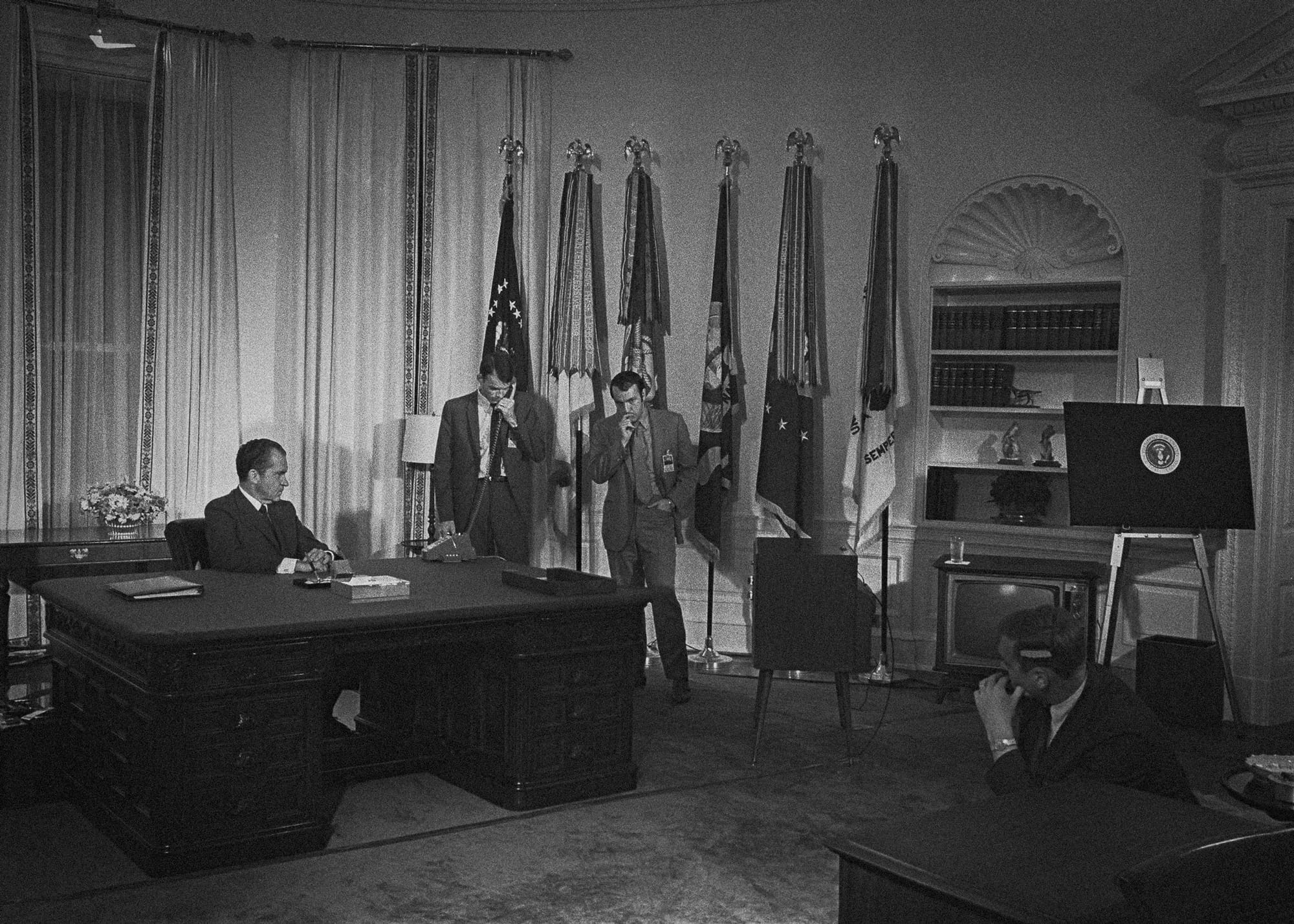

20 July 1969 – The White House watches

In another first, Armstrong was told that the President of the United States would like to say a few words to him, as he explored the Moon. After a few moments of quiet, a voice could be heard:

'Neil and Buzz, I am talking to you by telephone from the Oval Office at the White House, and this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made … Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world. As you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquillity, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquillity to Earth.’

NASA / NASA / Wiki Commons / NASA

60-66/91

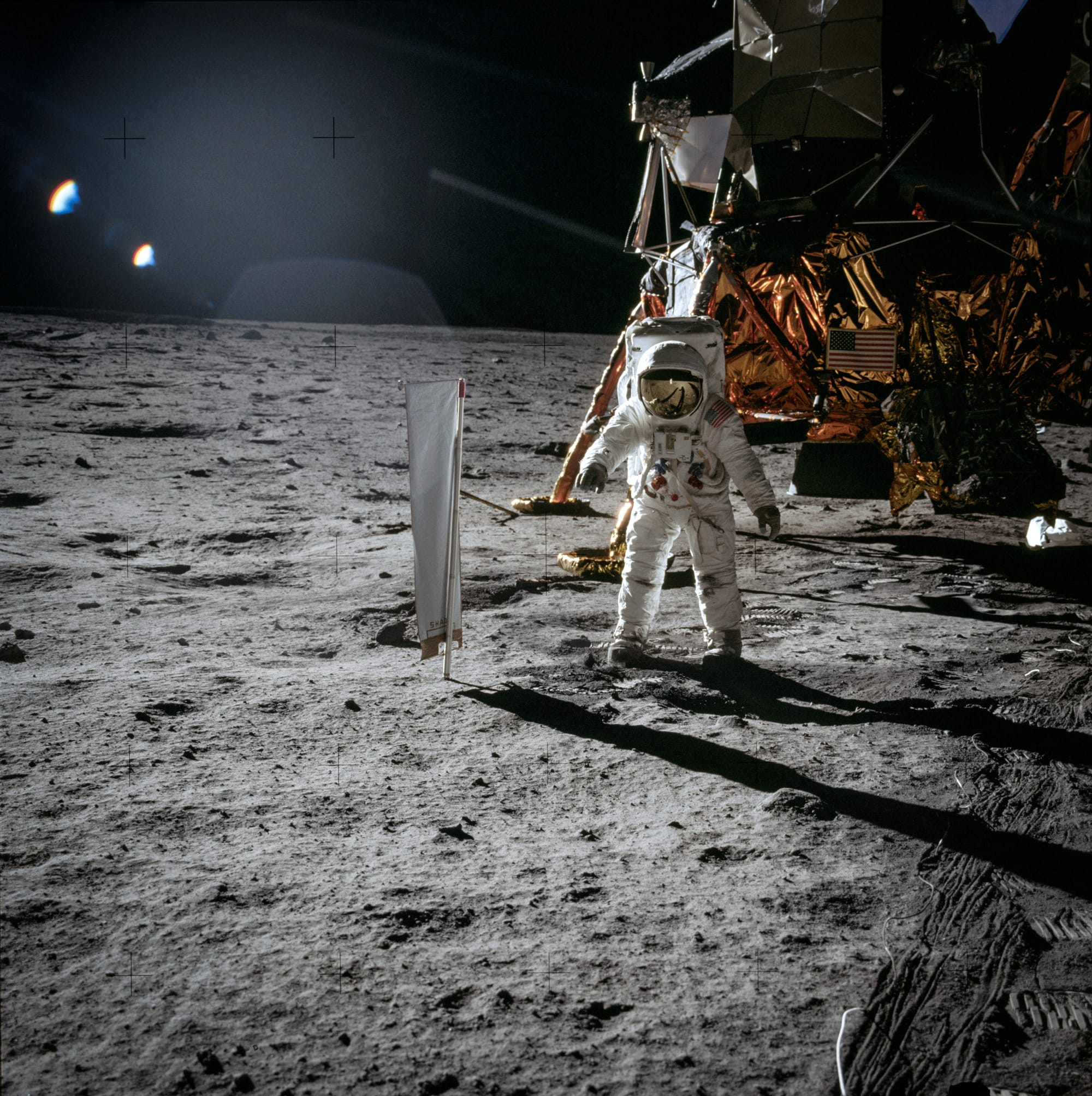

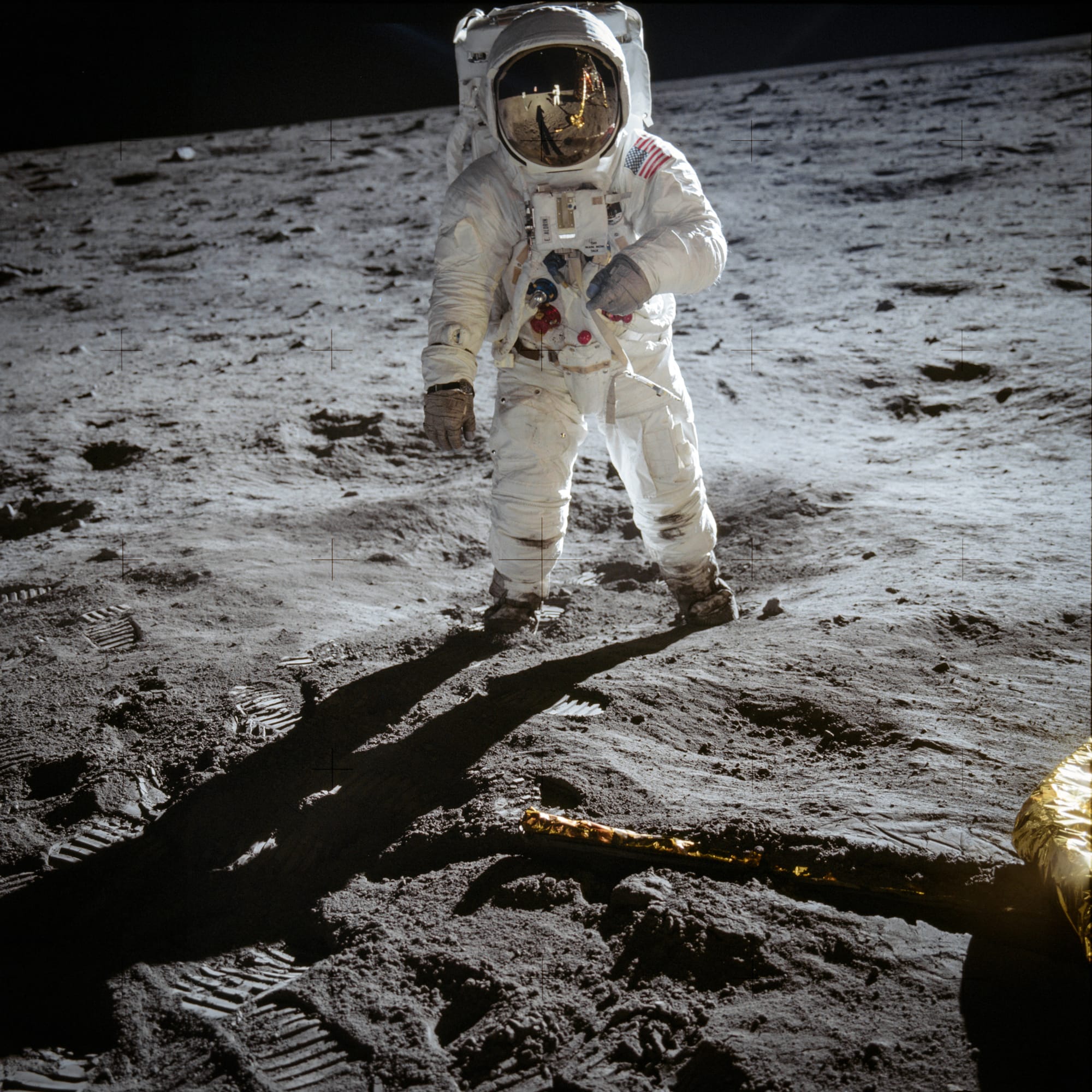

20 July 1969 – On the Moon

Text of the plaque left on the Moon's surface:

Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.

67/91

20 July 1969 – Scientists study data from the moon

Here we can see Dr Garry Latham, who worked with the Lamont Geological Observatory, studying tracings from a seismometer in real time.

Science was an essential part of the Apollo 11 mission. Several distinct experiments had been devised for the two astronauts to carry out.

The first was designed to measure 'moonquakes'; the second involved laser beams that were to be sent to the lunar surface from Earth. The third was formulated to enable the composition of gases in the solar wind to be studied in new detail.

68-69/91

20 July 1969 – Returning to the Lunar Module

These photographs of Armstrong and Aldrin are among the best known from the Apollo 11 mission. Armstrong's face in particular conveys a sense of giddy excitement as he comes to terms with what has just happened.

Indeed, Armstrong had little chance of fully comprehending his situation. Millions had watched him and Aldrin bouncing about on the Moon over the past two hours. In that time he had transformed into one of the most famous individuals alive.

A sample of Armstrong's sudden and colossal fame comes from Liverpool that day, where a 33 year-old lady called Olive Lee gave birth to a 8lbs 11oz baby boy. To mark the moment she selected the most fashionable of all name: Neil Armstrong Lee.

70-73/91

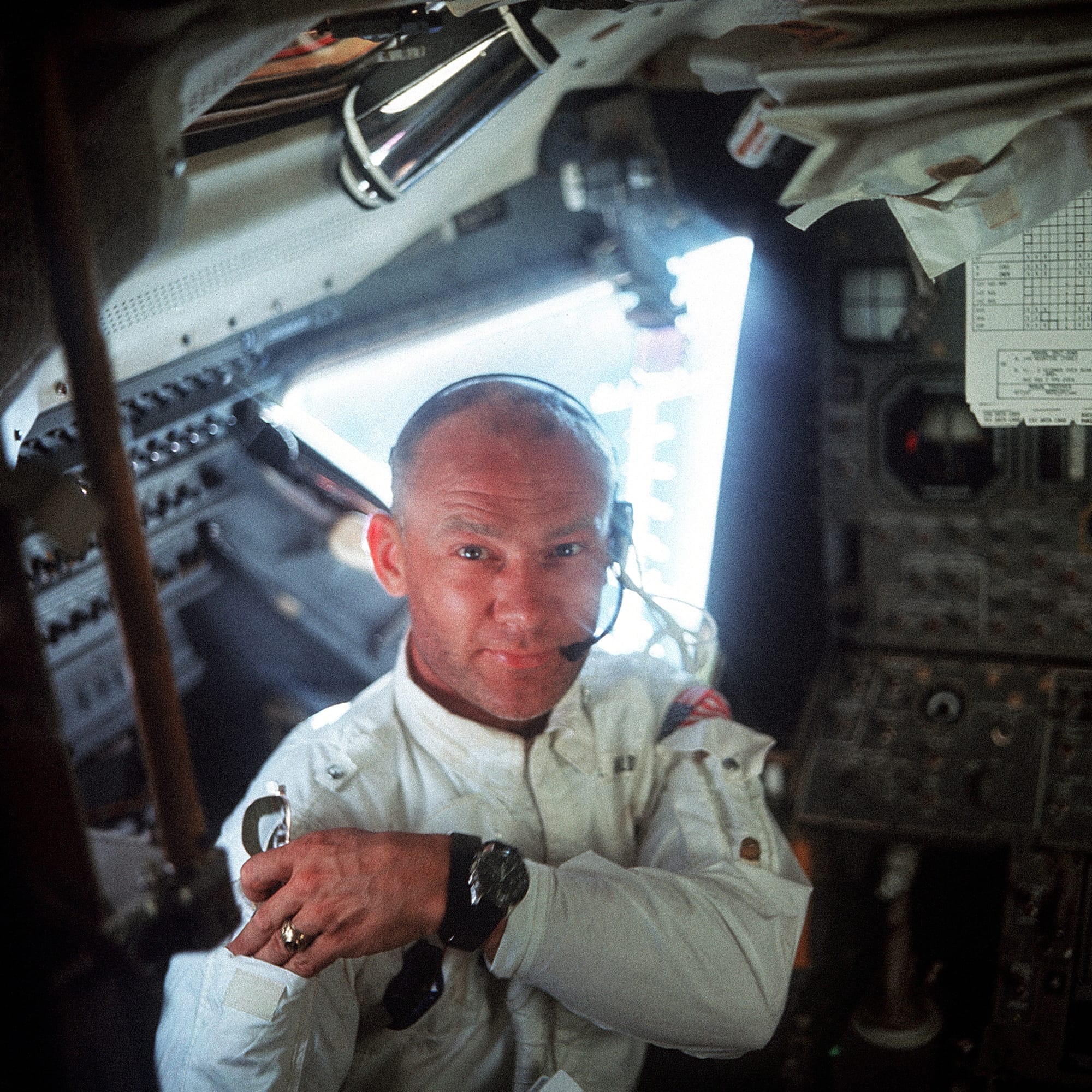

20 July 1969 – Returning to the Command Module

All the time Armstrong and Aldrin were on the Moon, Michael Collins remained far above them in lunar orbit.

For all the extraordinary nature of the landings, Collins's situation was, if anything, even more bizarre. He found himself truly in a situation that no other human in history had experienced.

'I am alone now, truly alone', he wrote as the command module passed around the far side of the Moon, 'and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two over the other side of the Moon, and one plus God only known what on this side.'

'I feel this powerfully — not as fear or loneliness — but as awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation. I like the feeling. Outside my window I can see stars — and that is all.'

74-75/91

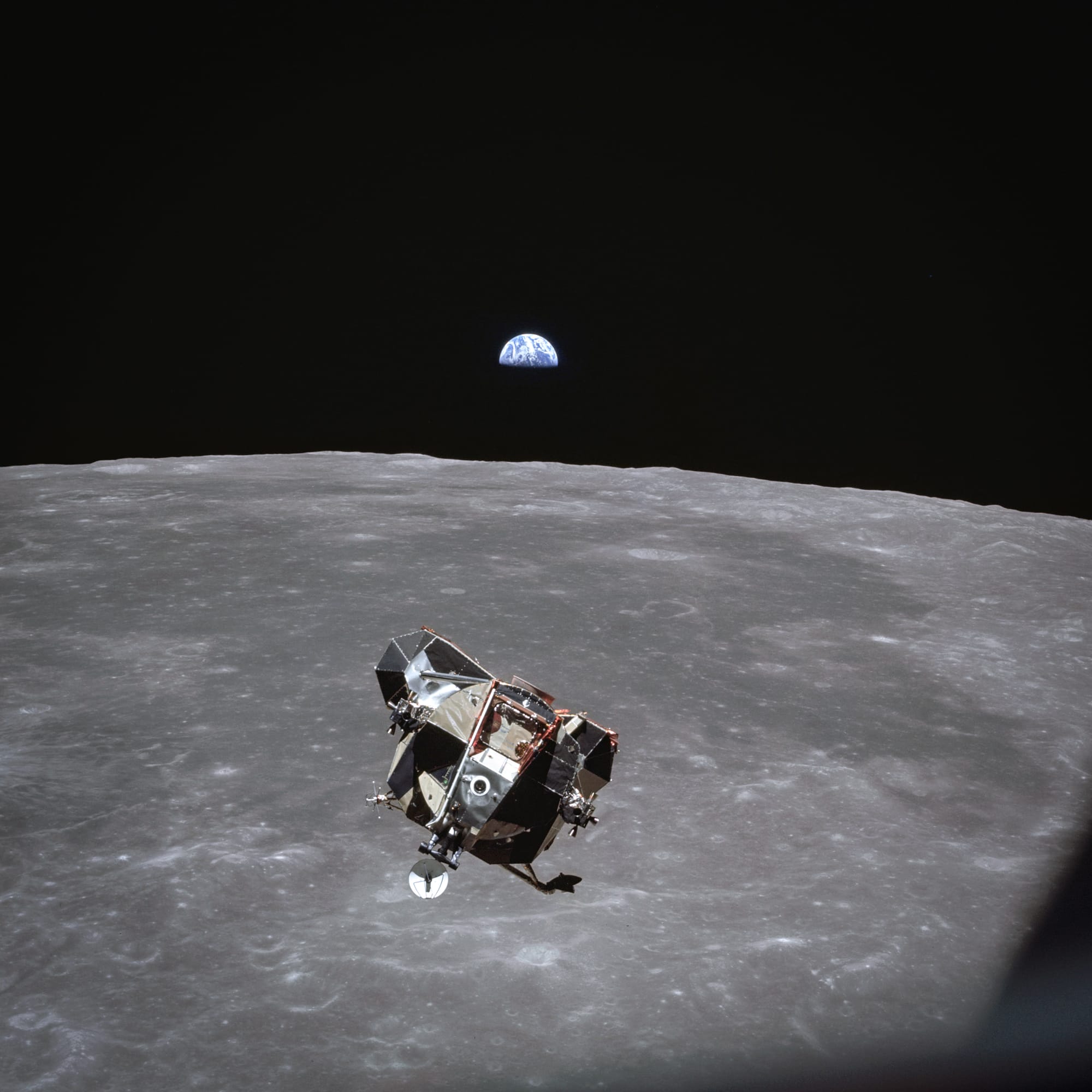

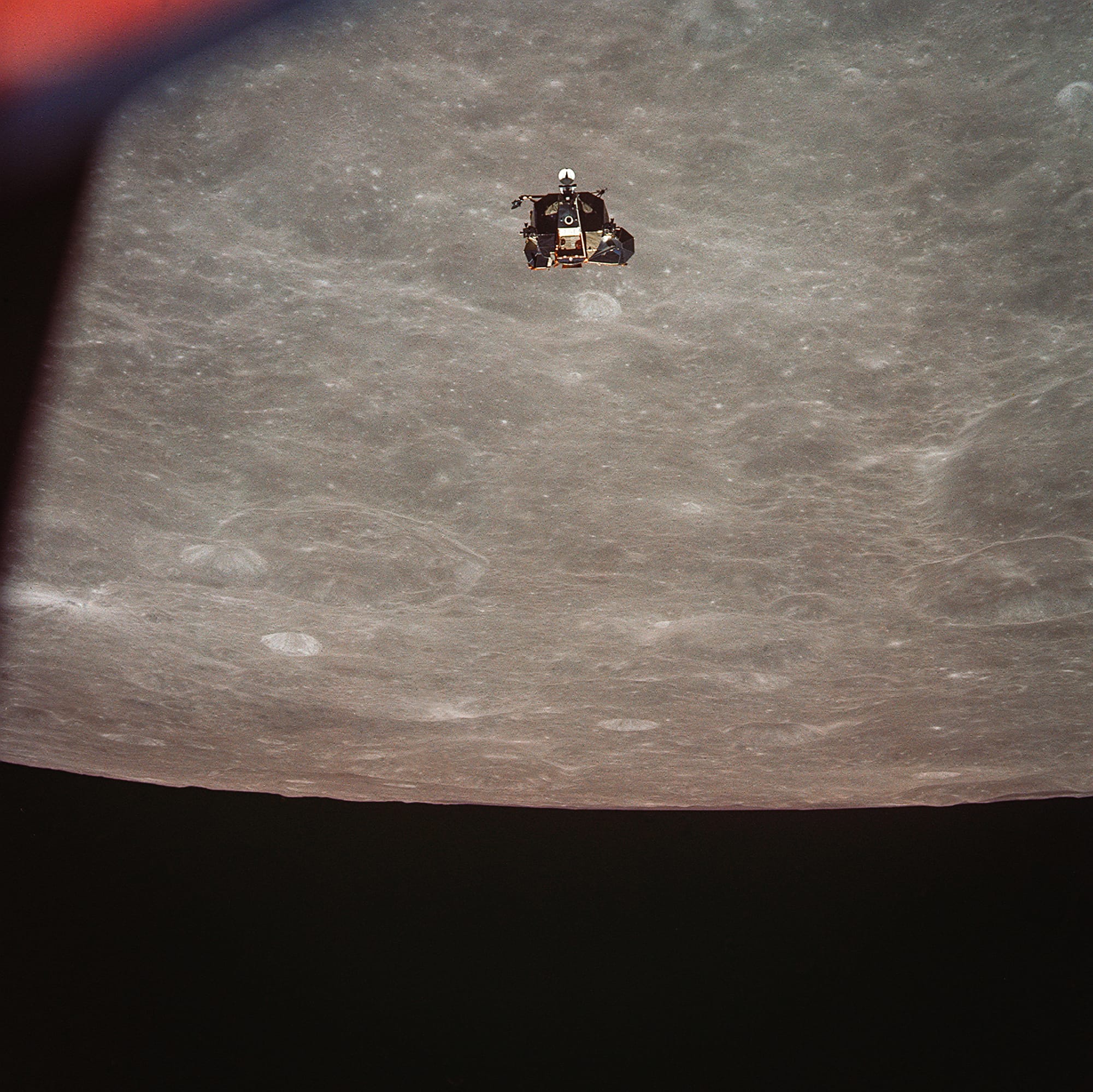

20 July 1969 – The Apollo 11 Lunar Module ascends

Collins's solitude was eventually broken by the return of the lunar module. The sight of Neil and Buzz returning, Collins later stated, was 'the best sight of my life'.

Collins's 'secret terror' for many months, had 'been leaving them on the Moon and returning to Earth alone'.

76-78/91

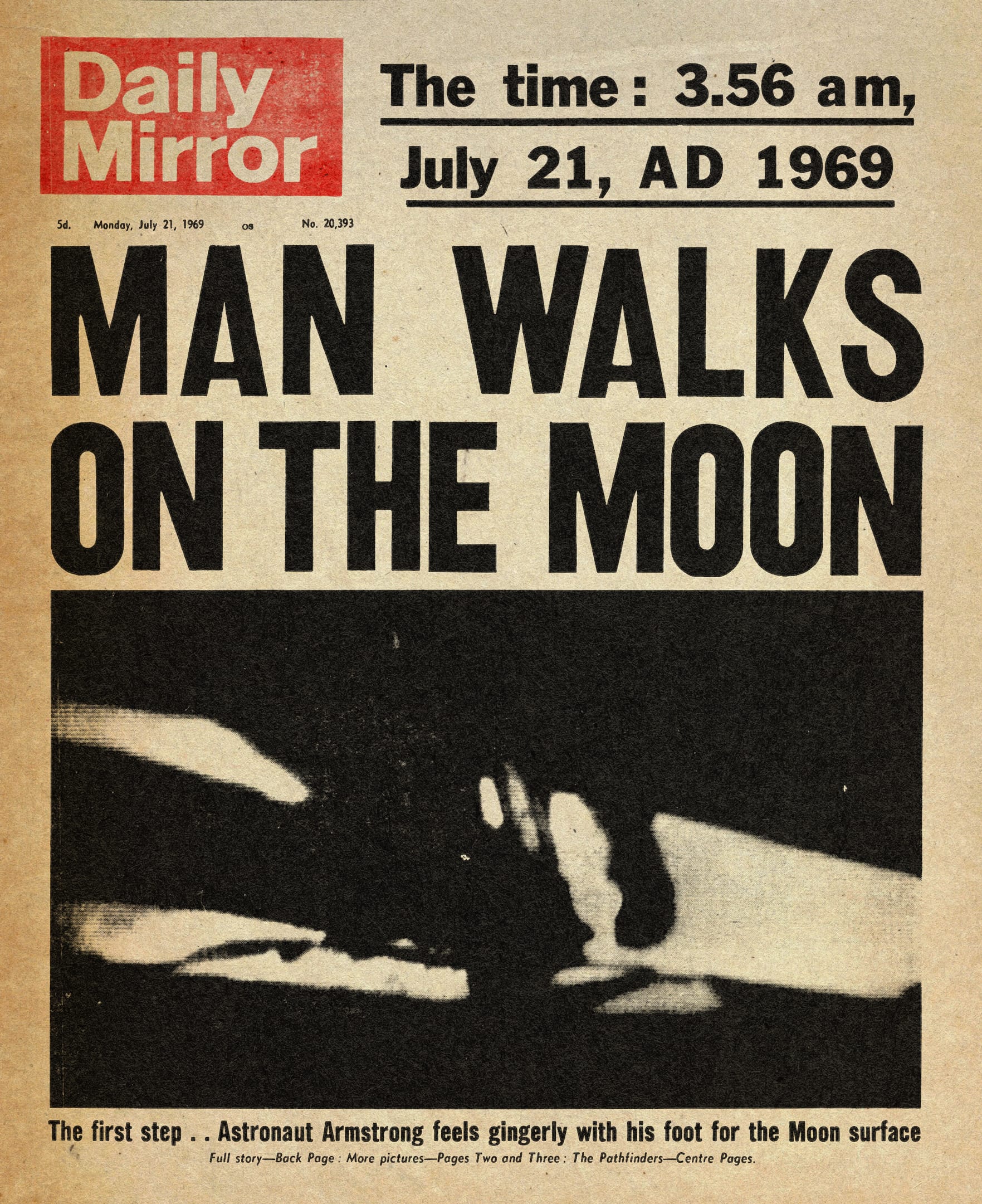

21 July 1969 – Headline news

News of Apollo 11's success led news bulletins across the world. It was a truly global story that crossed age boundaries as well as geographical ones.

In one poignant article about poverty in England, a reporter ended his piece with an anecdote about a book the family had been reading. 'When I was there', the journaist wrote, 'Richard who is the eldest asked his father, what was the reason for going to the Moon?

Mr Dow thought and smiled. ‘Can’t really say son,’ he said. ‘Guess they’ll tell us that when they get back.’

79/91

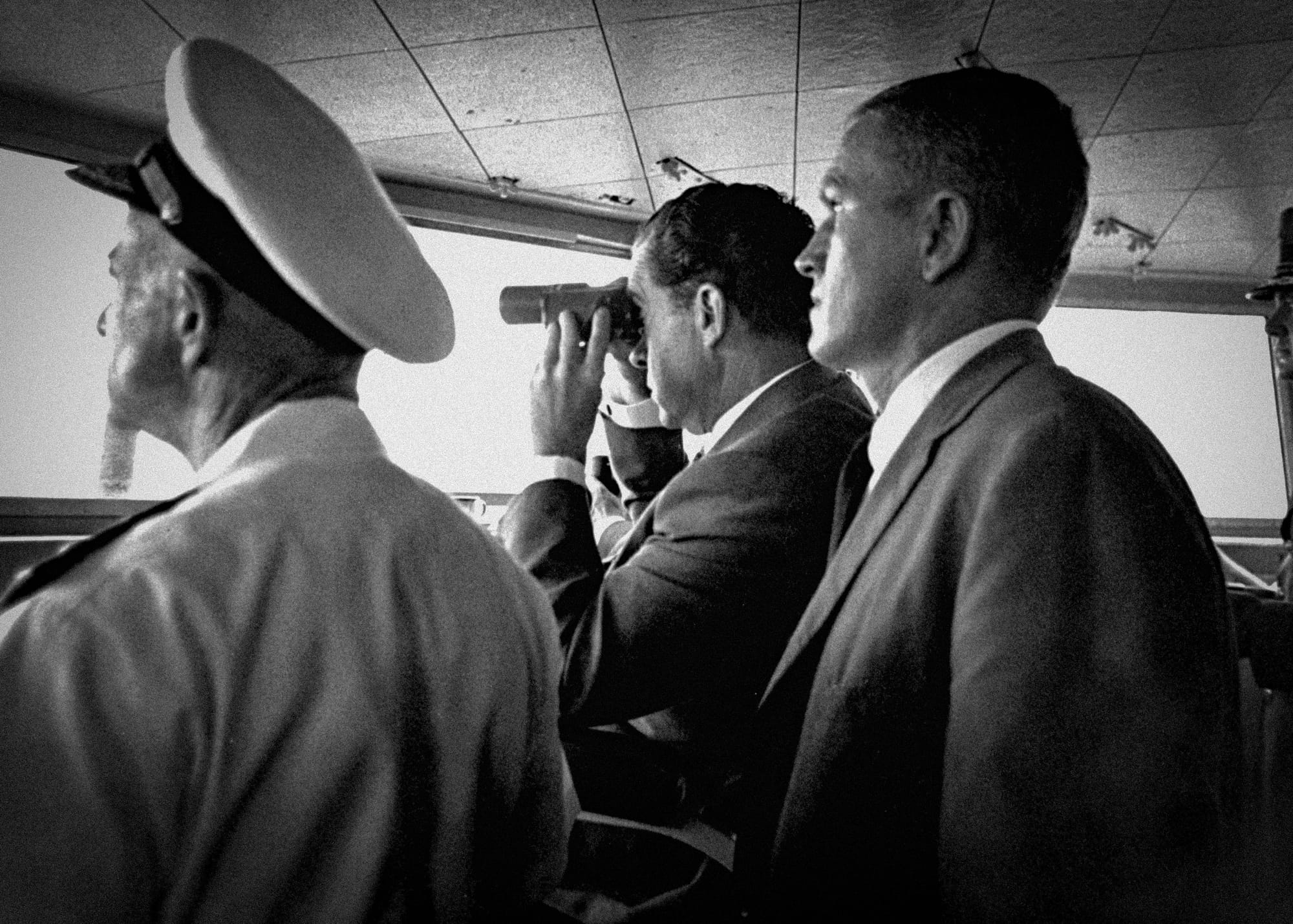

24 July 1969 – President Nixon on the USS Hornet

Richard Nixon, who was still in the first months of his presidency, took huge interest in the Apollo landings and ensured that he remained an active part of the story in the days after his phone call to the Moon.

Here he is pictured on USS Hornet, eagerly scanning the horizon for signs of the returning crew. Standing beside him is the astronaut Frank Borman, the commander of Apollo 8.

80-83/91

24 July 1969 – Splashdown

In the early morning of Thursday 24 July, 1969, the small remaining part of Apollo 11 spashed down in the mid-Pacific Ocean. Onboard, safe and healthy, were all three of the astronauts.

At Mission Control the tension broke as the craft hit the water. Soon the room was filled with people smoking cigars, waving miniature flags, shaking hands and wearing broad smiles.

In a perfectly choreographed moment, the large screen, on which all the televised action had played out throughout the course of the mission, darkened. Then Kennedy's words appeared:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.

– John F. Kennedy to Congress, May 1961

84-85/91

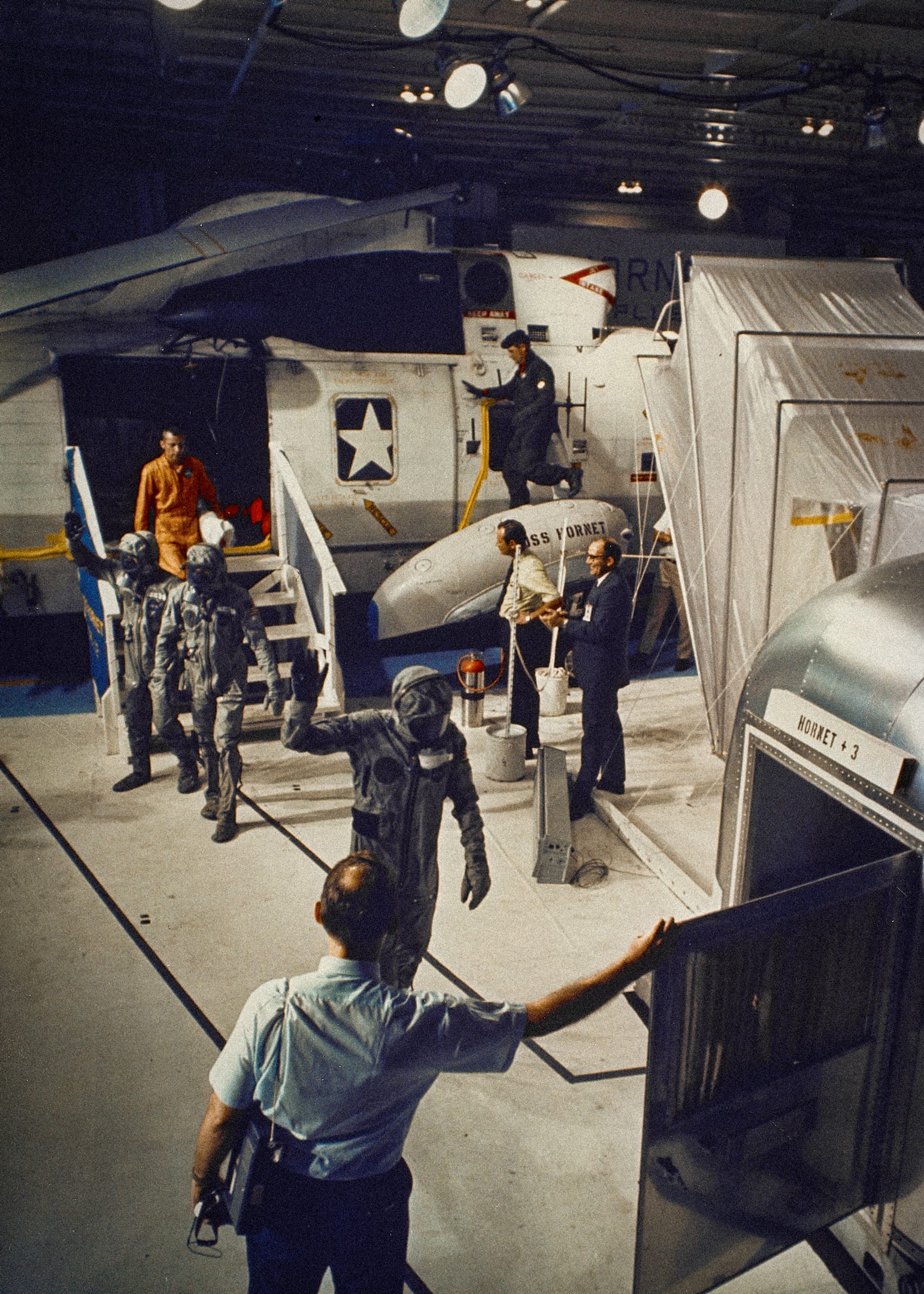

24 July 1969 – Into Quarantine

Having been collected from the Pacific Ocean, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins began their journey back to quarantine. Having been exposed to an unknown environment, a cautious approach was adopted in case they had returned to Earth carrying any lunar bugs.

This photograph captures something of this, but it also shows the three men very much in the roles of returning heroes.

They wave proudly to those watching on. There is a sense of poise and ease that is not apparent in many of the shots taken prior to the launch. An official dutifully holds open the door of a transportation vehicle as the three celebrities approach.

86/91

24 July 1969 – Dr von Braun and his son in Alabama

Also among the heroes on Apollo 11's after return was Werner von Braun. Many years had passed now since von Braun had arrived in Huntsville, Alabama, and to many of the locals he had been accepted in the years since as an eccentric European who worked on strange, powerful machines.

The regard in which he was held locally combined, in July 1969, with the enormous enthusiasm generated by coverage of the luar landings. Here von Braun can be seen as the focal point of a patriotic parade.

This marked a very peculiar culmination for his quite unique career.

87/91

24 July 1969 – Nixon meeting the astronauts

Having heard from President Nixon by telephone, the inevitable meeting followed once the astronauts were safely in their quarantine unit. Collins recalled his memory of the president, 'looking very fit and relaxed' standing just outside their window.

It was another disorienting moment for Collins, who described the woozy moment in the present tense:

'In a jovial mood he jokes a bit with us, nothing that Einstein’s theory of relativity decress that we have aged a bit less than our fellow earthlings during the days we have been spending in space, and that he has invited our wives – and us – to dinner. He wants to know if we got seasick, and Neil reassures him we did not, speaking over a hand-held microphone as the three of us crouch awkwardly at our low window. Then the President says, ‘This is the greatest week in the history of the world since the Creation ….’ and I lose track of the rest of his speech.

88/91

7 August 1969 – Freedom

Several weeks would pass before the returning astronauts were allowed out of their mobile quarantine facility. This moment captures a moment of reconnection when Neil Armstrong is welcomed by friends after his release. Behind Armstong you can see the domed head of Robert Gilruth.

Twenty others who had handled the Moon rocks were compelled to spend time in quarantine along with the astronauts.

As time passed, however, it became clear that there was absolutely no biological threat to Earth. With the release of these people, the final phase of the active part of the Apollo 11 mission drew to a close.

89/91

9 August 1969 – Sharon Tate's murder

If the Apollo 11 mission was a culmination of a promise made to the American people by President Kennedy eight years before, August brought more evidence that the carefree, aspirational culture of the past was giving way to something else.

Many have pinpointed the death of 60s innocence, or 'the knell of the counterculture' to the horrific series of murders that struck Los Angeles at about the time that the Apollo astronauts were leaving quarantine.

The most prominent of these was the killing of Sharon Tate, a Hollywood actress who was attacked and killed in her own home by members of the Manson Family.

90/91

9 August 1969 – A ticker tape parade in New York city

As the west coast absorbed the shock of these murders, across the country in New York a great parade was being planned. 'Moon Men Given Thunderous Welcome By Happy Americans', ran the headline to one article:

'Showered with tickertape and confetti so thick it was like a snowstorm in August, Apollo 11 astonauts Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E Aldrin and Michael Collins followed the route of America’s heroes through New York City’s financial district and up through Broadway.

Bands played, spectators — packed as tightly on the narrow sidewalk as subway riders at rush hour — yelled, cheered and surged through police barricades. Police had to struggle to keep the throng from engulfing the three men.

‘It’s wonderful. It’s exciting. The best part of all is being here' Armstrong said as he walked up the steps of City Hall for the official welcome to New York by a beaming mayor, Mr John V. Lindsay.'

91/91

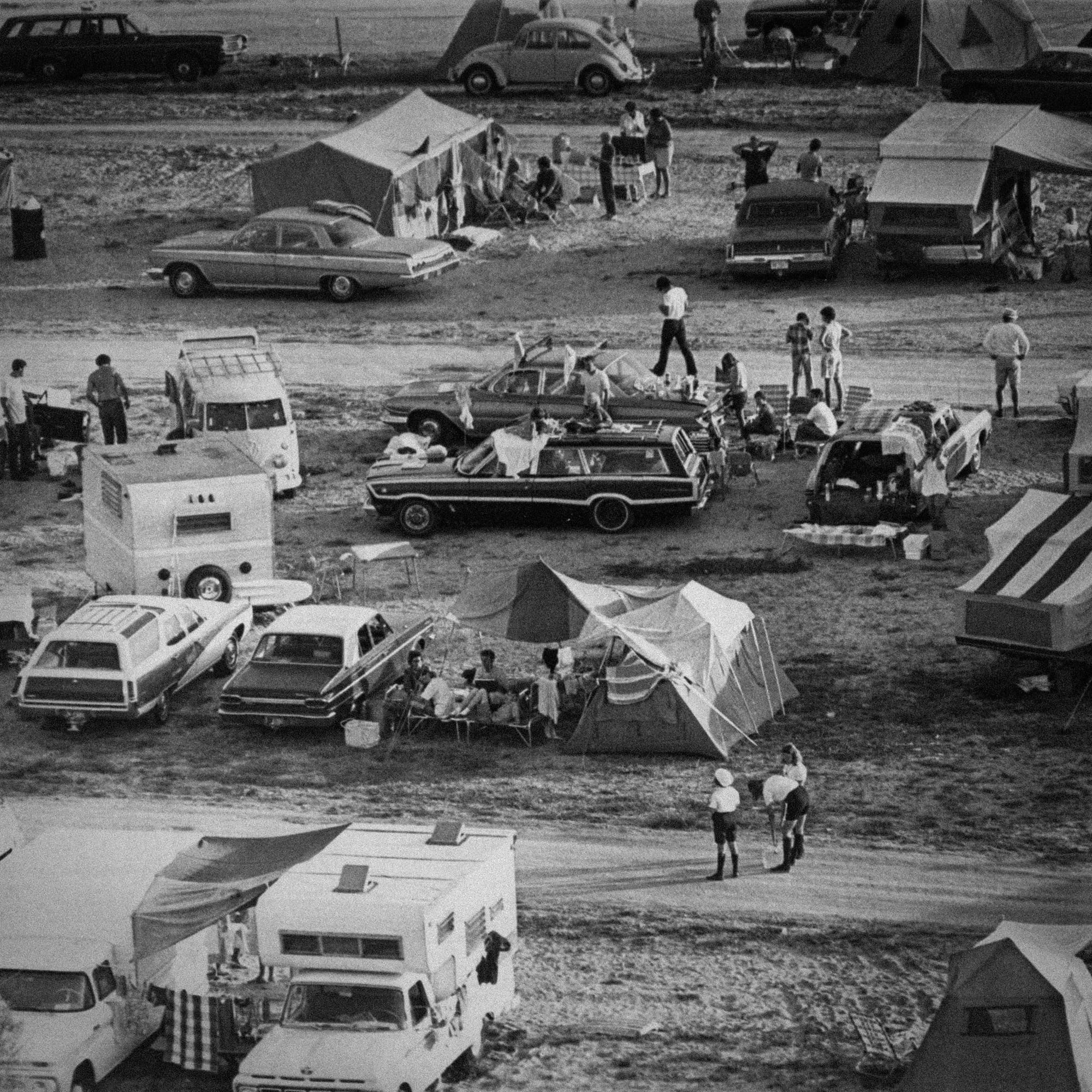

15 August 1969 – Woodstock Festival

It was in another part of the state of New York, however, that the summer's final grand story was to play out. In the rain-soaked countryside near Bethel, as many as 300,000 young people congregated for the mammoth 'Woodstock Music and Art Fair'.

This number, which was more than 100,000 in excess of what had been anticipated, watched performers like Joan Baez, Jimi Hendrix, The Jefferson Airplane, Ravi Shankar and The Who. Reports from the event, however, centred particularly on the lack of sanitation and food provided by the organisers.

Heavy rain, it was reported, poured down for hours on end, turning the 600 acre farm into a giant, seething mud bath. This in itself was only a continuation of rains that had dampened much of the high summer.

Interviewed during the parade in New York City several days earlier, Neil Armstrong had cheerily denied that the rains had anything to do with their trip around the Moon.

Extra medical help was called for from New York and three people were reported dead. One was run over by a tractor, another died from a heroin overdoe and a third from a burst appendix.

Colourful and chaotic, Woodstock was about a far from the precision engineering and bright, clean, geometrically precise Apollo mission as it was possible to be.

It provided a telling ending for an historic summer that was full of joy and angst, achievement and catastrophe, love and menace. The dreams of one president had been fulfilled but as a new decade drew nearer, there was still uncertainty about the future.

All that could be said for sure was that one age had passed. Another decade was about to begin •

This Viewfinder feature was originally published July 16, 2024.

More

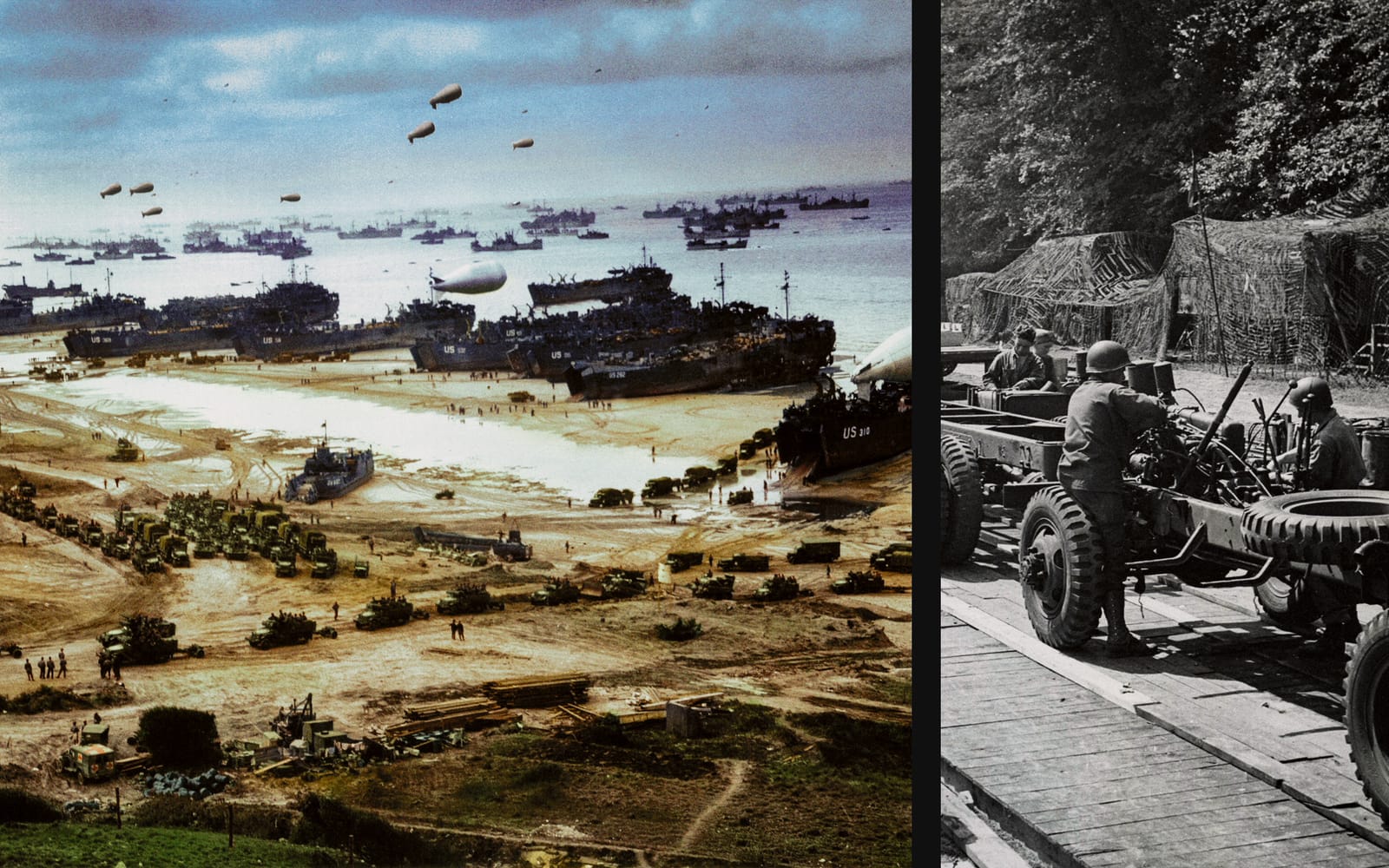

The Summer of 69 (Part 1 of 2)

The Moon landings gave the summer of 1969 its defining story. But elsewhere in the world many other events of consequence were playing out

References

This essay has been compiled from many sources. Chief among them are Michael Collins's memoir, Carrying the Fire, Charles Murray and Catherine Cox's Race to the Moon and the contemporary newspapers.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store