The Symbol of the Open Road Was Born at Sea

Tim Queeney explains the nautical origins of the steering wheel

There are between one and two billion cars on the world's roads today. Central to the control of all of them is the steering wheel, a device that symbolises freedom and the open road.

But as Tim Queeney, the author of the book Rope, explains here, the steering wheel evolved well away from any highway. It first appeared in the Enlightenment as a way to steer vessels at sea.

There are few things more iconic than the automobile steering wheel. From flashy chrome wheels of bulging 1950s American sedans to today’s padded techno wheels tricked out with buttons and switches, the steering wheel has been central in the process of getting from here to there.

The idea of a wheel for steering doesn’t originate with cars, however. It was the British Royal Navy in the early eighteenth-century that first devised wheel steering for its ships. And rope was the essential element in making the wheel the premier method for setting direction.

The steering wheel is so much a part of automobile culture that it’s hard to think of it any other way. From rocker Neil Young writing about a wheel in an old Lincoln sedan in his book Special Deluxe, A Memoir of Life and Cars, 'The steering wheel was beautiful, sculpted in a wonderful aged ivory color with a nice chrome ring and a beautiful Lincoln emblem in the center on a black background. The car was a piece of art.' to Dutch band Golden Earing singing '…driving all night my hands wet on the wheel.' in their 1973 hit Radar Love.

In the Age of Sail, sailors were equally taken by the steering wheel. Witness the wooden ship’s wheels adorning the walls of harbor pubs and the references in nautical poems like the oft-quoted Sea-Fever by John Masefield '… and all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by; and the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking.'

Why did sailors identify with the wheel? To understand that we need to look at the two devices that were used to steer a ship before the wheel was invented: the tiller and the whipstaff.

The adoption of the centerline rudder, which replaced side-mounted steering oars, gave rise to the use of the tiller. This was a long piece of wood attached to the top of the rudder. The tiller extended into the ship to give the helmsman mechanical advantage in turning the rudder.

To steer, the helmsman pushed on the tiller and that moved the rudder in the opposite direction. For example, to turn to the left (known as port in maritime parlance) the tiller is pushed to the right (starboard). This moves the rudder to the left and the ship turns to the left or port.

To turn to starboard the helmsman moves the tiller to port. Small sailboats are still steered using a tiller and when you learn to sail it soon becomes second nature that to turn to starboard you move the tiller to port and to turn to port you move the tiller to starboard.

As sailing ships grew ever larger in the late medieval and renaissance eras, helmsmen pushing a tiller around became increasingly difficult due to the higher forces involved. Larger ships also meant that the part of the ship where the tiller was located was built ever higher so the helmsman was surrounded by ship structure and couldn’t see the sails or the sea.

This led to the development of the whipstaff, a long pole that was attached to the end of the tiller and then passed up through the deck to the level above. A special fitting called a rowle was employed where the whipstaff passed through the deck. When he pushed on the whipstaff, the helmsman was also be pushing on the end of the tiller on the deck below him. This would move it side to side, with the rowle acting as the fulcrum point.

The whipstaff was an improvement, but ships continued to get larger and even the whipstaff deck became encased by ship structure. This meant that the helmsman usually only had a few small windows with which to see the sails. And from his position inside the hull he couldn’t view the sea surface at all.

As a result the helmsman had to rely on a fellow crewmember or a ship’s officer on deck to give him direction on steering. They would have to shout their instructions down to him as he worked the whipstaff from side to side. For the helmsman then, it was a challenging job as he was almost completely cut off from a view of the outside.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries some clever naval designers began to think about this steering issue. They rightly noted the use of rope all over a sailing ship for controlling the yardarms and the sails. And many of these control lines used pulleys (pulleys are called blocks in nautical terminology — why do sailors have a different name for everything? That’s a subject for another article!).

These blocks increase the mechanical advantage for the sailors hauling on the ropes. So, designers began to think: 'What’s a way we can use mechanical advantage and rope to do a better job steering?'

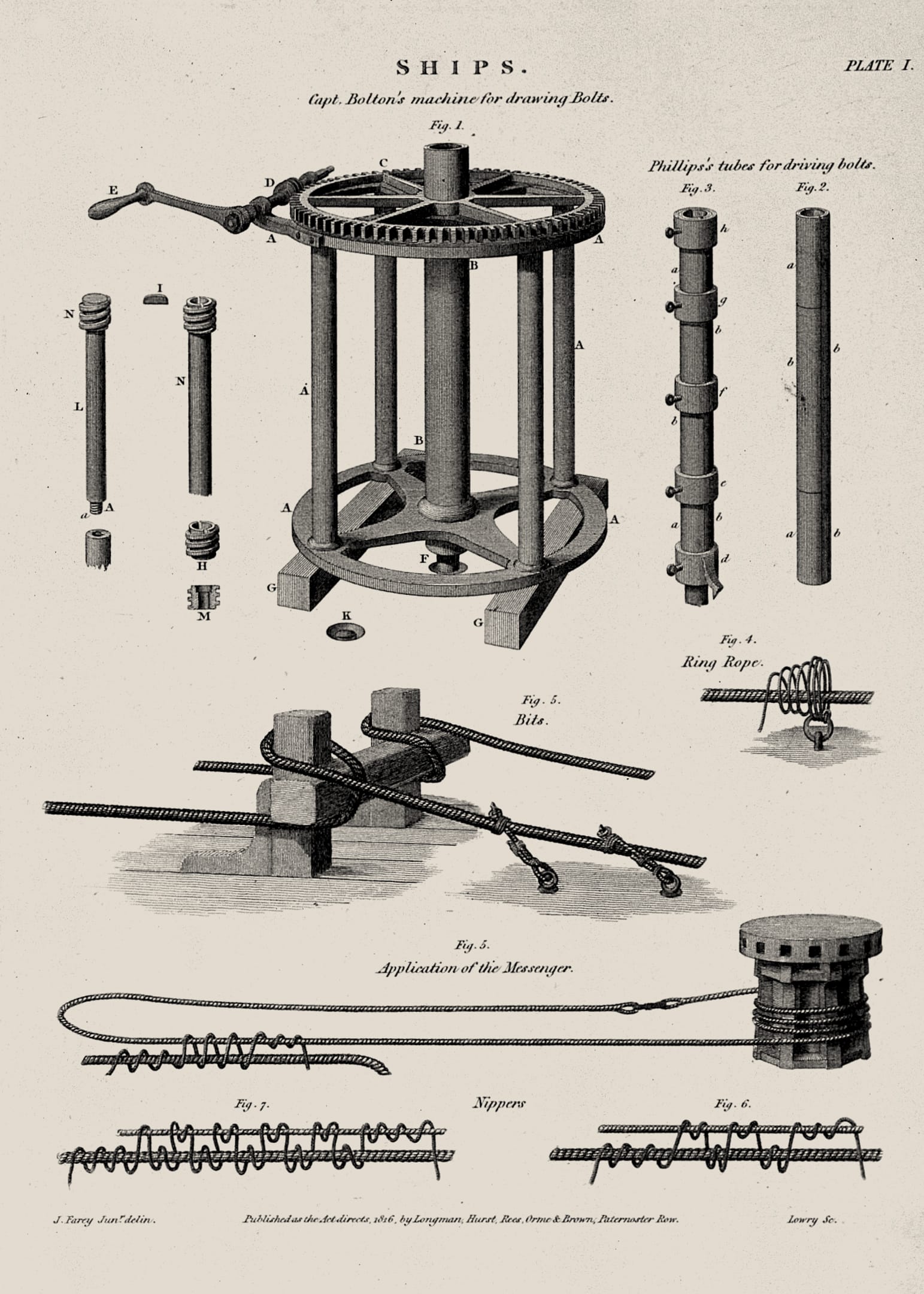

The solution was to adapt a device called a windlass and put it into the steering role. A windlass is nothing more than a cylindrical drum around which rope wraps as the drum is turned. Windlasses were used on cranes for lifting objects. Handles attached to the ends of the drum allowed workers to turn the drum to take up the lifting rope.

This same basic approach was used for this new steering idea. A barrel drum was fitted with spoked wheels (just like the wheels found on a horse-drawn wagon). The spokes were extended beyond the rim of the wheel to act as handles. This drum was set up so the long axis of the drum, which the rope wound around, was aligned fore and aft.

The design included one spoked wheel on the end of the drum closest to the back of the boat and one spoked wheel on the other end of the drum. Around the drum itself a rope was wound several times. The ends of this were led down through gratings into the tiller room below.

One end was led through a turning block on the port side and then attached to the end of the tiller. The other was similarly fed through a turning block on the starboard side and then attached to the other side of the tiller.

The result of this arrangement was a sort of closed-circuit windlass. When the steering wheel at either end of the drum was revolved, it turned the rope drum and pulled on the rope attached to one side of the tiller. That swung the rudder in the opposite direction. When the wheel on deck was turned the other way, it pulled the tiller over in the opposite direction, which moved the rudder the other way.

This new type of wheel steering moved the helmsman from a place below deck to a position on the top deck. The helmsman could now see the sails and the water.

This made the job of helming a ship much more intuitive since the helmsman wasn’t dependent on getting an endless stream of instructions shouted down to him. He could make corrections based on his knowledge and experience of how the ship moved in the wind and waves.

Liberated from the whipstaff, the ship’s helmsman became the forerunner of the automobile driver at a chrome-studded wheel, enjoying the freedom of the open road •

This feature was originally published September 2, 2025.

Rope: How a Bundle of Twisted Fibres Became the Backbone of Civilization

Icon, 14 August, 2025

RRP: £20 | 336 pages | ISBN: 978-1837733316

Tim Queeney is a sailor who knows more about rope and its importance to humankind than most. In Rope, Queeney takes readers on a ride through the history of rope and the way it weaves itself through the story of civilization.

From Magellan's world-circling ships, to the 15th-century fleet of Admiral Zheng He, to Polynesian multihulls with crab claw sails, he shows how without rope, none of their adventurous voyages and discoveries would have been possible. Time traveling, he describes the building of the pyramids, the Roman Coliseum, Hagia Sofia, Notre Dame, the Sultan Hasan Mosque, the Brooklyn Bridge, and countless other constructions that would not have been possible without rope.

Not content to just look at rope's past, Queeney looks at its present and possible future and how the re-invention of rope with synthetic fibers will likely provide the strength for cables to support elevators into space. Making the story of rope real for readers, Queeney tells remarkable nautical stories of his own reliance on rope at sea. Rope is history, adventure, and the story of one of the world's most common tools that has made it possible for humans to advance throughout the centuries.

“Like all good books about technology, then, 'Rope' is ultimately about human beings at their best and worst”

– New York Times Book Review

With thanks to Amelia Kemmer.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store