Escaping Auschwitz

Monisha Rajesh recounts one of the most poignant 'untold railway stories'

When the first railways were introduced in the early nineteenth-century they were regarded as objects of wonder. But the pioneers could never have foreseen the disturbing use their invention would one day be put to.

In the 1940s western Europe's developed rail network played a significant role in the Holocaust. During the Second World War huge numbers of Jews were loaded into waggons and transported by rail to the extermination camps in the east.

In this excerpt from the collection, The Untold Railway Stories, Monisha Rajesh recounts the story of one young boy who narrowly survived this persecution.

For references please consult the finished book.

Sitting up, eleven-year-old Simon Gronowski strained to listen in the darkness. With an ear-splitting screech the train had braked and come to a standstill, and he could now hear voices and what sounded like footsteps. Gunshots rang out followed by shouts in German, but with no windows and nothing more than a small hatch in the wall of the cattle truck in which he rode, Simon had no idea what was happening outside.

A few minutes later the train set off again. In the arms of his mother, Chana, Simon soon fell asleep on the straw-covered floor, where they lay surrounded by fifty other people, many of whom were crying and groaning. It wasn’t long before another disturbance woke him. The truck’s doors were open, a cold wind billowing through, and he saw that two deportees were preparing to leap from the moving train.

Taking him by the hand, Chana drew Simon towards the doorway. This was what he’d been practising for, leaping off bunk beds back at the transit camp. But now, with the ground rushing by, Simon was too nervous to jump. The two others leapt into the moonlit night and Simon perched on the edge of the doorway, his feet dangling. Chana lowered him by the shoulders until he was standing on the footplate between the ground and the truck. Suddenly the train braked and Simon took his chance, landing squarely on the opposite tracks, without a scratch or bruise. Waiting for Chana to follow, he looked back as the train sped up and she called out in Yiddish. ‘It’s going too fast!’ Those were the last words Simon would ever hear from his mother. With a shrill whistle the train steamed on towards its final destination at Auschwitz.

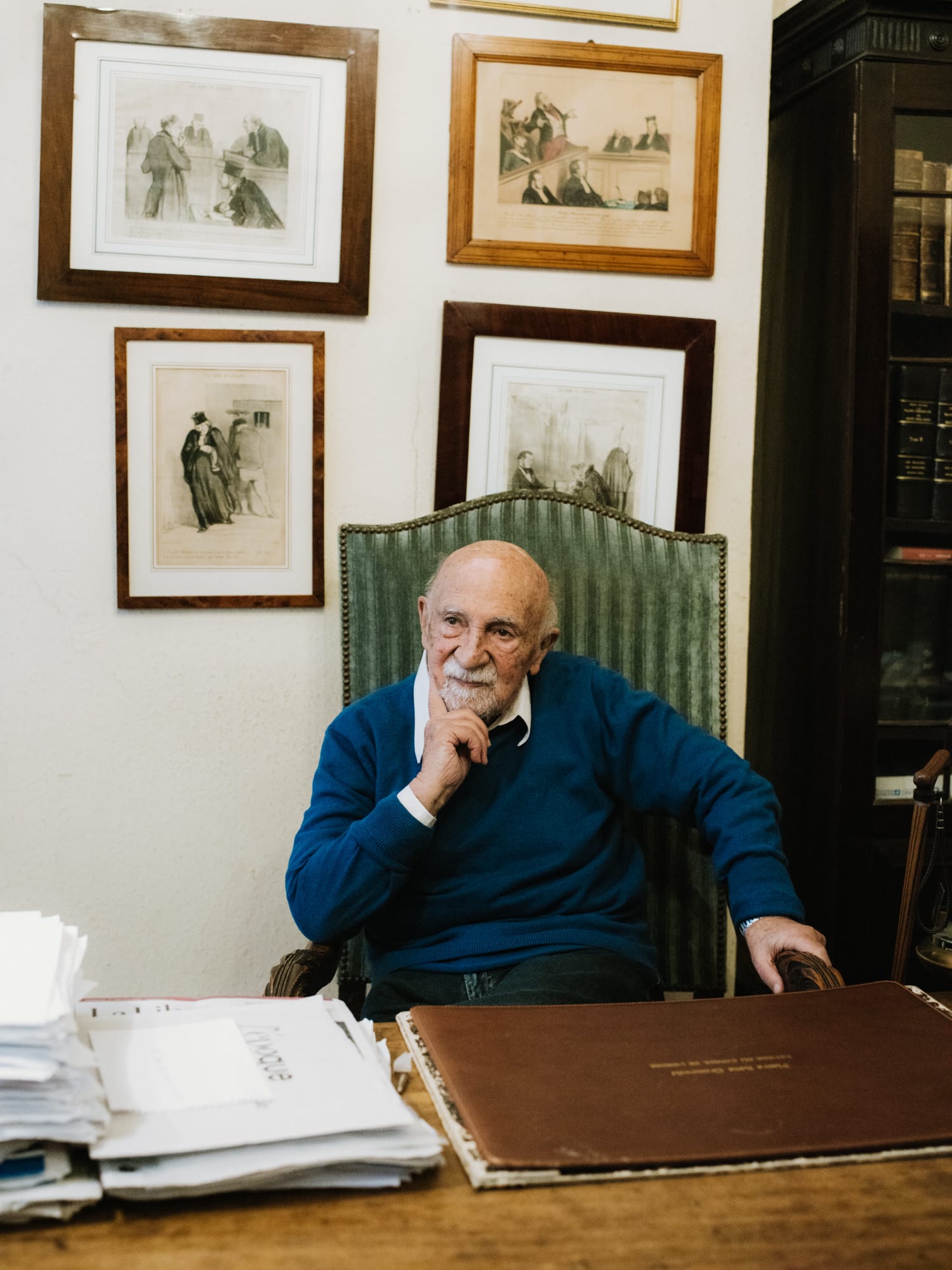

His eyes moist, ninety-one-year-old Simon Gronowski is now sitting behind the desk at his home in Brussels, recounting to me the events of the extraordinary night of 19 April 1943. After jumping, he had stood waiting for Chana in the cold. Through the darkness he heard cracks of gunfire and screaming. Simon quickly realised that if his mother attempted to escape she would only end up in the arms of the Gestapo, so he turned and fled through the woods and across the wheat fields of Flanders.

‘My first idea was to go back to my cattle car and get back in with my mother so the Nazis wouldn’t find me outside the train,’ Simon says. ‘If the guards found me they would have shot me immediately. I was all alone. Two or three jumped out before me but I had no idea where they were.’

Pressing a hand to the side of his head, Simon stares in silence at the desk before looking up. ‘To get back to my mother I would have had to run past the Germans, so I turned left and I ran.’

Between 1942 and 1944 the Nazis deployed 28 trains to deport the 25,490 Jews and 353 Roma detained at the Dossin military barracks, a transit camp in the city of Mechelen in Flanders, to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Early in the morning on Monday 19 April 1943 – the eve of Passover – a train drew up in front of the barracks. For the previous nineteen deportation trains that had travelled from Mechelen to Auschwitz, the Nazis had used third-class passenger trains. On those trains, the doors were locked but the windows remained open and a number of deportees had successfully escaped with assistance in the form of tools and weapons from Resistance fighters: 13 in total from the first 15 transports; up to 248 from transports 16 and 17; and 67 from transports 18 and 19.

According to Dr Laurence Schram, an expert on the genocidal deportation of Jews and Roma from Belgium, the SS in Brussels realised they needed to adapt the deportation procedure to ensure the trains arrived in Auschwitz unhindered. Starting with Simon’s train, the convoys would be composed of goods wagons and would leave at night, with a reinforced guard to prevent Jews from jumping off the trains. In accordance with new law, the twentieth convoy comprised thirty cattle trucks with doors secured by barbed wire and barred hatches instead of windows. The trucks blocked the view of residents across the road, rendering them unable to witness the loading of deportees onto the train throughout the day.

Simon and his mother were two of the 1,631 deportees packed onto train 801 who sat in darkness until the 10 p.m. departure. The deportation of Jews was common knowledge among Belgian society and the Resistance against the occupation was strong, but Simon is adamant that their final destination was unknown.

‘No one knew. Nobody. They thought they were going to be taken to a labour camp somewhere. The Nazis drew a veil over the fact that it was a death camp we would be sent to. I was there for a month and we didn’t hear the word Auschwitz even once.’

A month earlier, Simon, his eighteen-year-old sister Ita and their mother had been rounded up by the Gestapo and taken to the transit camp. At the time of their arrest Simon’s father, Léon, had been in hospital recovering from lung problems that he’d developed as a miner and he was now in hiding in Brussels.

In the face of pogroms and antisemitism in Poland, Léon had fled the country in 1921 and entered Belgium illegally as an undocumented migrant. He had married Chana, a Lithuanian, and their two children were classified as foreign nationals until the age of sixteen, when Belgian law dictated that they could choose their nationality. When she turned sixteen, Ita had chosen Belgian nationality, and at the time of the family’s arrest the Nazis were not deporting Belgian Jews, so Ita was detained separately from her little brother and mother.

‘I said goodbye to my sister and of course I had no idea I would never see her again,’ says Simon. ‘She was not deportable but she was not free either.’

Other deportees had made plans to escape from the train with members of the Resistance, who had been smuggling in weapons in food parcels up until the day of departure. In the barracks children had been practising their jumps, but it was implausible that gas chambers awaited their arrival.

It was only after the war that Simon would learn what had taken place that night on the twentieth convoy.

With little time to prepare, three young members of the Resistance – old schoolfriends named Youra Livchitz, Robert Maistriau and Jean Franklemon – had devised a plan to ambush the train and free as many deportees as possible. They were aware of rumours about the destination and had chosen a spot east of Brussels, near the town of Boortmeerbeek, knowing that the deportees had a greater chance of making it to freedom within Belgium’s borders, where the population was more likely to help. They chose a curve in the tracks where the train would be travelling slowly, one that was close to woods in which the escapees could hide from the Gestapo.

A little after 10 p.m. the trio set off on their bicycles armed with nothing but a single pistol and some pliers. It was a windy night and clouds flitted across the sky as they rode towards the railway line. Robert placed a hurricane lamp wrapped in red paper on the tracks to serve as a makeshift stop signal and the trio went into hiding in nearby bushes and trees. They waited. Minutes passed, then in the distance Robert heard the sound of a whistle. The train was approaching. Slowing into the bend, the engine rolled over the hurricane lamp, then came to a standstill to the tremendous sound of braking. With no time to waste, Robert bolted towards the nearest truck and began to cut open the barbed wire with the pliers, pulling open its doors. Inside, he was greeted by the shocked faces of deportees unsure whether or not to jump. With encouraging shouts in both French and German, he spurred them on, handing each one a 50-franc note to enable them to return to Brussels. This was to be the only successful and documented ambush of a deportation train throughout the years of the Holocaust.

Although Simon didn’t escape at the point of ambush, the action fired up a number of those on board who managed to break open doors and saw at bars on the hatches, allowing further escapes. In total 233 prisoners fled the train, of whom 118 survived.

After three nights on the move across Europe the train arrived in Auschwitz. It carried 1,398 deportees – 877 were immediately murdered in four newly enlarged gas chambers, Chana included.

‘I ran through the night,’ says Simon. ‘Because I was a cub scout I was prepared and I knew I would get out of it somehow. Before we left the barracks my mother gave me a 100-franc note which I put in my sock. She was already preparing my escape. While running, I was humming to myself. I hummed “In the Mood” by Glenn Miller. It was my sister’s favourite song and she used to play it on piano. She loved jazz…’ He smiles at the memory of his sister. Five months after Simon’s escape, Ita was also transported to Auschwitz and gassed on arrival.

At dawn Simon came upon a village and chose to seek refuge in a small worker’s house – the big houses were often occupied by the Nazis. When a woman answered the door he claimed he’d been playing nearby with children and got lost. This explanation made no sense: a little French-speaking boy in Flanders, fifty miles from Brussels, wearing torn clothes covered in mud. Without asking any questions, the woman asked her neighbour to take him by bike to a kindly gendarme, who offered to help. Simon fell sobbing into his arms and told him everything that had taken place. The gendarme’s wife fed and bathed Simon and dressed him in her son’s clothes. The gendarme then took him back to the station and helped him to buy a ticket for the train to Brussels.

On arrival Simon went into hiding in a family friend’s home, while his father lay low in a separate location. For seventeen months Simon moved between houses, scared that he would be caught and praying that God would bring back his mother and sister.

‘I changed houses three times during that period,’ says Simon, holding up three fingers on a small hand. ‘And every time I arrived I went up to the attic to see if there was an escape over the roofs. To see if I could flee. Every time the bell rang I was scared stiff. During this time I only left the house two or three times in total.’

On 3 September 1944 Brussels was liberated and Simon was reunited with his father.

‘We were waiting for my mother and my sister to come back. But when the Allies went into Germany they discovered all the concentration camps and they found the gas chambers and the crematoria and the mountains of bodies, and my father realised that they were never coming back. He died on 9 July 1945 of a broken heart.’

Now a practising lawyer and jazz pianist, Simon sits surrounded by papers, legal memorabilia and books, bringing out a postcard Ita had written to him and thrown from her deportation train. It detailed how ‘we are leaving and being taken to work on farms in Holland’, the rumour the Nazis had propagated to keep people calm. It had reached Simon’s hands long after her death. But in spite of the horrors of his youth, Simon remains positive about the human condition.

‘I remain an optimist. I don’t want to send out a message of sadness but one of hope and happiness. I say that life is beautiful. I fight for peace and equality among all people.’

Nonetheless Simon has given up his Jewish faith and become atheist, believing that if God had existed he would never have allowed the Holocaust to happen.

‘What’s beautiful is that witnessing it directly, you then become witnesses in your own terms. Another reason I speak is because I want to thank those who risked their lives to save me. I want to thank the three young men who attacked my train.’

Youra Livchitz went on to be captured and executed in February 1944, refusing to be blindfolded in front of the firing squad. Jean Franklemon was arrested in August 1943 and deported to concentration camps in Germany but survived the war, dying in 1977. Robert Maistriau was arrested and transported to the Buchenwald concentration camp in May 1944, but survived and moved with his family to the Congo before his death in Belgium in 2008 •

This excerpt was originally published September XX, 2025.

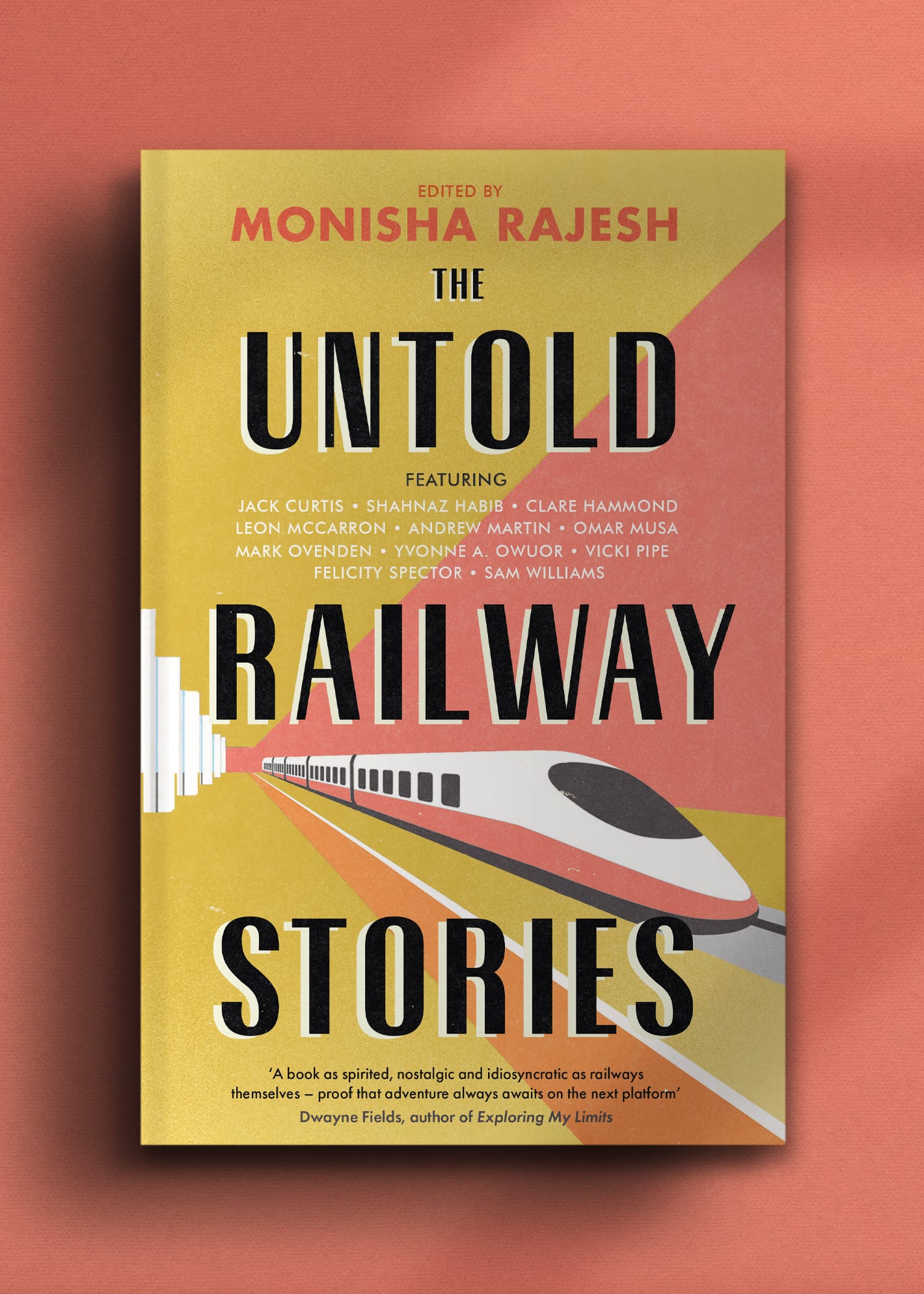

The Untold Railway Stories

Duckworth, 11 September, 2025

RRP: £22 | ISBN: 978-0715656082

A compendium of fascinating and evocative new writing on railway travel and history. Telling of little known journeys and uncovered histories on railway routes around the world - from the UK, Europe and Africa to North America, the Middle East and Asia.

From Myanmar's highlands to the British Pennines, from slow travel between coffee plantations in Borneo to a cross-continent odyssey on African railways, from the pioneers of the American West to European trains in war, this is a new prism through which to explore human lives, and global landscapes, politics and history.

The Untold Railway Stories is a testament to both the joy and impact of train travel - to the ambition and ingenuity, and also to destruction and sacrifice within its history - and is published to coincide with the 200th anniversary of first passenger railway line.

Edited by Monisha Rajesh; with stories from Monisha Rajesh, Shanaz Habib, Clare Hammond, Mark Ovenden, Vicki Pipe, Leon McCarron, Andrew Martin, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Sam Williams, Omar Musa, Felicity Spector and Jack Curtis.

With thanks to Angela Martin.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store