The Vatican, the War and the Pope's Secret Bank

Yvonnick Denoël takes us back to the Second World War and the Vatican's efforts to secure their wealth

Italy was a central theatre of conflict during the Second World War. Under Benito Mussolini it formed a central part of Hitler's Axis Alliance. By 1943, on Mussolini's fall, the country became a battleground itself — subject to invasions from north and south.

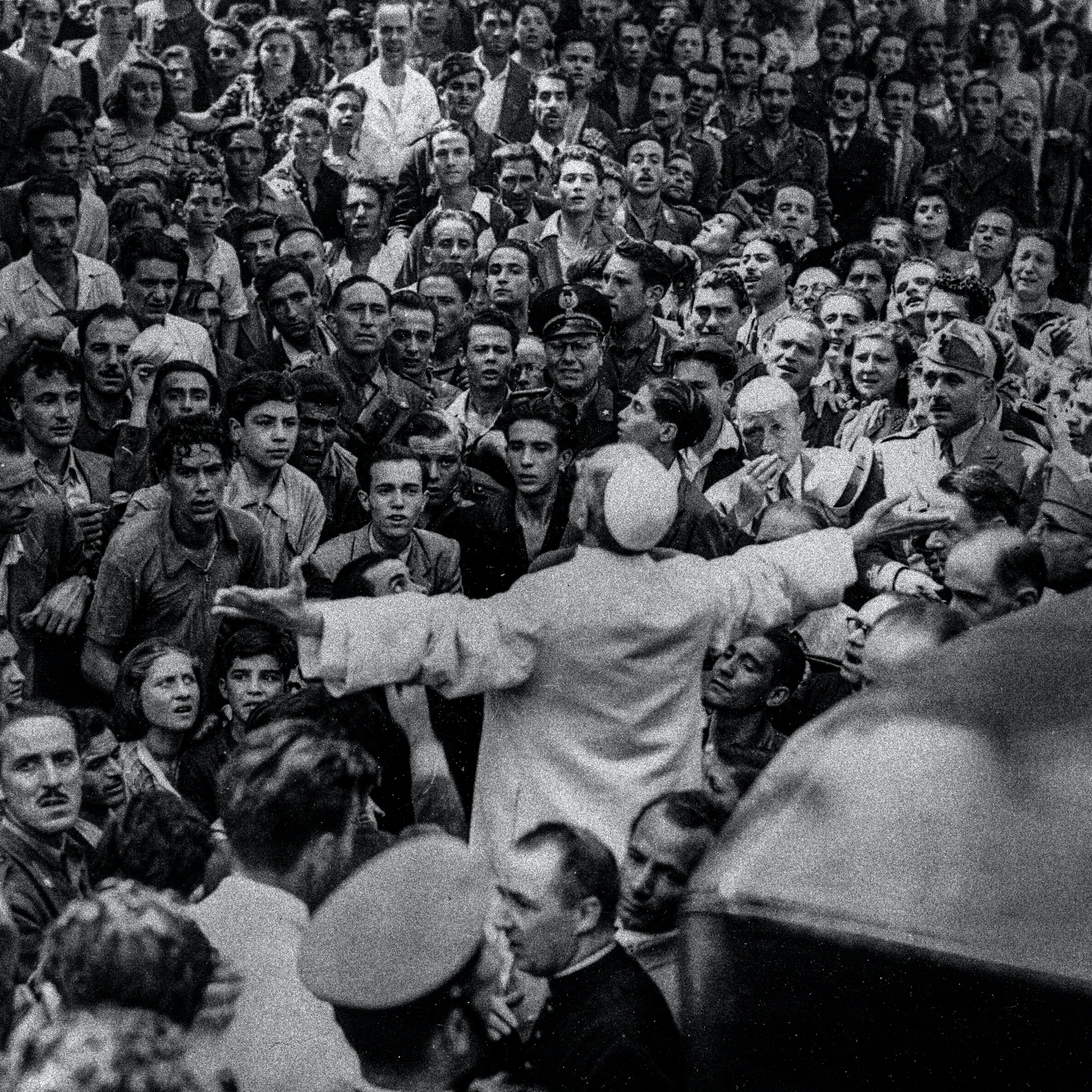

Caught in the midst of this was the tiny Vatican City State in Rome. Formed in 1929 as a sovereign country by the Lateran Treaty, it was from here that Pope Pius XII sought to steer the Roman Catholic Church through the turmoil of war.

Politics and God were one thing. Money was another. And as the war approached the Church confronted the challenges of safeguarding and retaining their wealth.

As the author Yvonnick Denoël explains in this extract from his newly-released book, Vatican Spies, this task devolved to an intriguing figure called Bernardino Nogara.

Excerpted from Yvonnick Denoël's Vatican Spies: From the Second World War to Pope Francis.

'Saving the Church's Heritage'

Apart from the Pope himself, the Vatican in theory had a lot to lose, from a financial point of view, from a German invasion in September 1943. To avoid a disaster, a financial person had taken exceptional precautions—a very discreet person who played a far from negligible part in our story.

To understand his role we have to return to the Lateran Pacts. To manage his new fortune in 1929, the Pope needed a trustworthy person. He found him in the person of Bernardino Nogara, a well-known banker in Italy.

Nogara's main asset was the fact that he had started off as the right-hand man of a Venetian financier, Count Giuseppe Volpi (Mussolini’s future minister of finance), who sent him to the four corners of his empire: he was thus a manager of mines in Bulgaria, as well as the head of a financial agency in Constantinople, where he ran a network of informers which enabled Volpi to keep an eye on all business opportunities.

After World War I, Nogara was part of the delegation of Italian experts at the Versailles Peace Conference and represented Italy at the Inter-Allied Commission, supervising Germany’s reconstruction. Four of his brothers had taken Holy Orders, two had become archbishops, and a third ran the Vatican Museum.

That being said, Nogara was very suitable according to the requirements of the moment. In 1929, Pius XI created the Special Administration of the Holy See (ASSS) and appointed Nogara at its head, with full authority to manage the endowments received as a result of the Lateran Pacts.

Nogara undertook to diversify the Vatican’s investments by moving the funds in the Banco di Roma to other banks and by investing in the railways and industries of other European countries like France and Germany.

From October 1929, he was confronted with the great world crisis starting with the Wall Street Crash. In 1933, the Vatican admitted it had lost more than 100 million lire. Its annual income was seriously reduced.

Nogara decided to turn part of the Holy See’s assets into gold (entrusted to the Morgan Bank in New York) and to invest in real estate and various countries’ treasury bonds, working through a Luxembourg holding company and giving them absolute discretion.

As a director of the Franco-Italian bank Sudameris, established in South America, Nogara undertook to diversify its banking channels, notably with the Union des Banques Suisses (UBS).

Nogara became a prominent person among the Italian political and economic elites, the equal of Alberto Pirelli or Giovanni Agnelli. In the end, he managed to stabilise and protect the endowments of the Vatican during the crisis.

During the Second World War, his good relations with big American financiers benefited the Vatican. Thanks partly to Nogara and partly to Spellman, the Holy See was the only European state able to carry out transactions with both the Allied and the Axis powers.

Indeed, as soon as America entered the war, the president signed an executive order blocking all transactions with the Axis countries and those placed under their control. Italy was obviously part of this. European countries like Switzerland and Andorra which had proclaimed their neutrality were also involved. In short, all Europe was involved—except the tiny Vatican city-state, which was nonetheless at the mercy of Mussolini.

The White House did not want to alienate American Catholics and, above all, Roosevelt remembered that in 1936 he had been visited by Secretary of State Pacelli, who was shown around by Spellman: Catholic voters were seen as having political clout and they voted for the most part for the Democratic Party in 1940.

The British were less accommodating of the Pope’s financier. Their Ministry of Economic Warfare suspected Nogara of playing a double game. After all, ever since 1925, he had been a director of the biggest Italian bank, BCI, which was considered an enemy entity.

The same applied to its subsidiary, the Banca della Svizzera Italiana, which was put on the blacklist because of its dealings with Nazi companies. Finally he held an interest in Sudameris, which was also on the blacklist for its Nazi connections. In short, the Allies had every cause to impose sanctions on the Vatican, instead of which they were happy just to protest to Secretary of State Maglione, who in turn assured them of the Holy See’s neutrality.

Some responsible American and British people wondered if Nogara wasn’t playing a double game: was the Vatican really the owner of the considerable stocks of shares and bonds that Nogara deposited with J.P. Morgan in New York?

It was suspected, but it could not be proven, that he was laundering these shares for money that made its way into the accounts of their real owners, wanting to smuggle out some of their assets. But how does one investigate the Church?

In June 1942, the Vatican went a step further in its quest for financial secrecy: it created its own bank, the IOR (the Istituto per le Opere di Religione, or Institute for Religious Works), which did not submit to any foreign regulations, paid no taxes to anybody, and did not publish any accounts.

Until 2000, it was even authorised to destroy its records regularly. This institution was completely independent inside the Church (it will be discussed again later). It enabled Nogara’s transactions to disappear from the international radar. The bank could receive shares and money: in principle, it only accepted priests, religious orders and other charitable institutions as customers.

But in practice, it soon became the preserve of rich Italians and others, worried about looking after their capital. Nogara was soon staggering under the requests made to him and discovered a new business model for his bank, an unexpected source of income. Easy money? Certainly. On the moral side, it left a lot to be desired.

The bank was used as cover for international speculation: clergymen close to the Pope were sent as couriers to get across the borders with large sums of money in cash and securities. Spellman himself played a key role: during his military trips, the archbishop never travelled without suitcases containing gold, shares and bonds in safe custody, as well as foreign currency in cash, worth several million dollars each time.

Armed with American safe conducts, he was never worried. Dozens of trustworthy priests organised more modest flows, notably towards Switzerland. In all, several hundred million dollars were safely put away in this way.

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the American secret service created in 1942, became interested in the IOR’s activities. In 1944, its agents discovered that the Reichsbank had transferred funds on several occasions to the Vatican via a Swiss bank. The information was explosive, but no follow-up was ever made. The United States had a war to finish ■

Vatican Spies: From the Second World War to Pope Francis

Hurst, 5 December, 2024

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1911723400

‘Officially’ the Vatican has no espionage service; but does no one carry out intelligence operations on its behalf?

During the Second World War and Cold War, Rome was teeming with spies. A band of undercover monsignors and priests hunted for Vatican ‘moles’, led clandestine diplomacy, investigated assassinations of priests and other scandals threatening the Church, and conducted high-risk missions behind the Iron Curtain.

Drawing on freshly released archives of foreign services that worked with or against the Holy See, Vatican Spies reveals eighty years of shadow wars and dirty tricks. These include infiltrating Russian-speaking priests into the Soviet Union; secret negotiations between John XXIII and Khrushchev; the future Paul VI’s close relationship with the CIA; the Vatican’s infiltration by Eastern Bloc intelligence; the battles between the Jesuits and Opus Dei; and the secret bank funds channelled first to fight communism in South America, then to support Solidarity in Poland.

This entertaining book journeys right to the present, uncovering startling machinations under Benedict XVI and, today, Pope Francis.

"An intriguing book... an informative resource on the modern papacy. It will certainly satisfy all those who, after watching Conclave, want to learn more about intrigue in the Holy See." – Sunday Times

"A no-holds-barred account of the Vatican’s covert operations … is revelatory … The Vatican is so secretive that the book becomes a modern history of the Holy See. There is much blood on the carpet." – The Observer

Additional Credit

With thanks to Raminta Uselytė. This excerpt is republished with permission from Yvonnick Denoël.