The Voynich Manuscript

Garry J. Shaw on the world's most mysterious manuscript

The Medieval Age was a time of great form and elegance, craftmanship and colour.

These qualities are present in many of the beautiful illustrated manuscripts that were created in those centuries. Produced by hand and rich in meaning, many of these manuscripts continue to enchant scholars today.

But among them all the Voynich Manuscript, discovered in 1912 and kept today at Yale University, has a particular appeal.

Here Garry J. Shaw, the author of Cryptic, tells us about the world's most mysterious manuscript.

Produced in the early fifteenth century, and bearing an unreadable text with strange illustrations, the Voynich Manuscript is regarded as the world’s most mysterious manuscript, a reputation that has only strengthened over the past century as every attempt to decipher it has failed.

Over the years, researchers have tried to connect the manuscript with every conceivable language. They have attempted to link it with far-flung and exotic places. Scholars have also sought to establish connections with famous figures like Leonardo Da Vinci and John Dee.

The manuscript has featured in TV shows, movies, and books. It has inspired music and its digital edition remains one of the most-viewed pages on the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s website – the Yale University library where it is held.

Today, despite years of scrutiny, its mystery stubbornly persists. What does the latest research reveal about this most mysterious of manuscripts?

Even after Violet’s first round of frauds were exposed, many still believed she was telling the truth. In fact, her original inheritance scam was so perfectly orchestrated it has become the perfect prototype for almost every inheritance fraud since.

The Manuscript

Flicking through the Voynich Manuscript’s 240 vellum pages, what usually first grips any hopeful decipherer is its unusual, unreadable script.

Despite its unique appearance, some of its characters seem familiar, particularly those resembling Arabic numerals like “4” and “8.” Others bear similarities to the letters “a” and “c”, while another looks like two “P”s standing back to back, linked by a horizontal line.

There’s also an upside down “v”, and an “x” with a looped peak. As the text cannot be read, it’s unclear how many symbols comprise “Voynichese” – this all depends on how they can be separated – but there could be between thirty-four to seventy characters in total. Intriguingly, the scribes appear to have made only a few corrections during the composition, suggesting that they were well versed in its peculiarities.

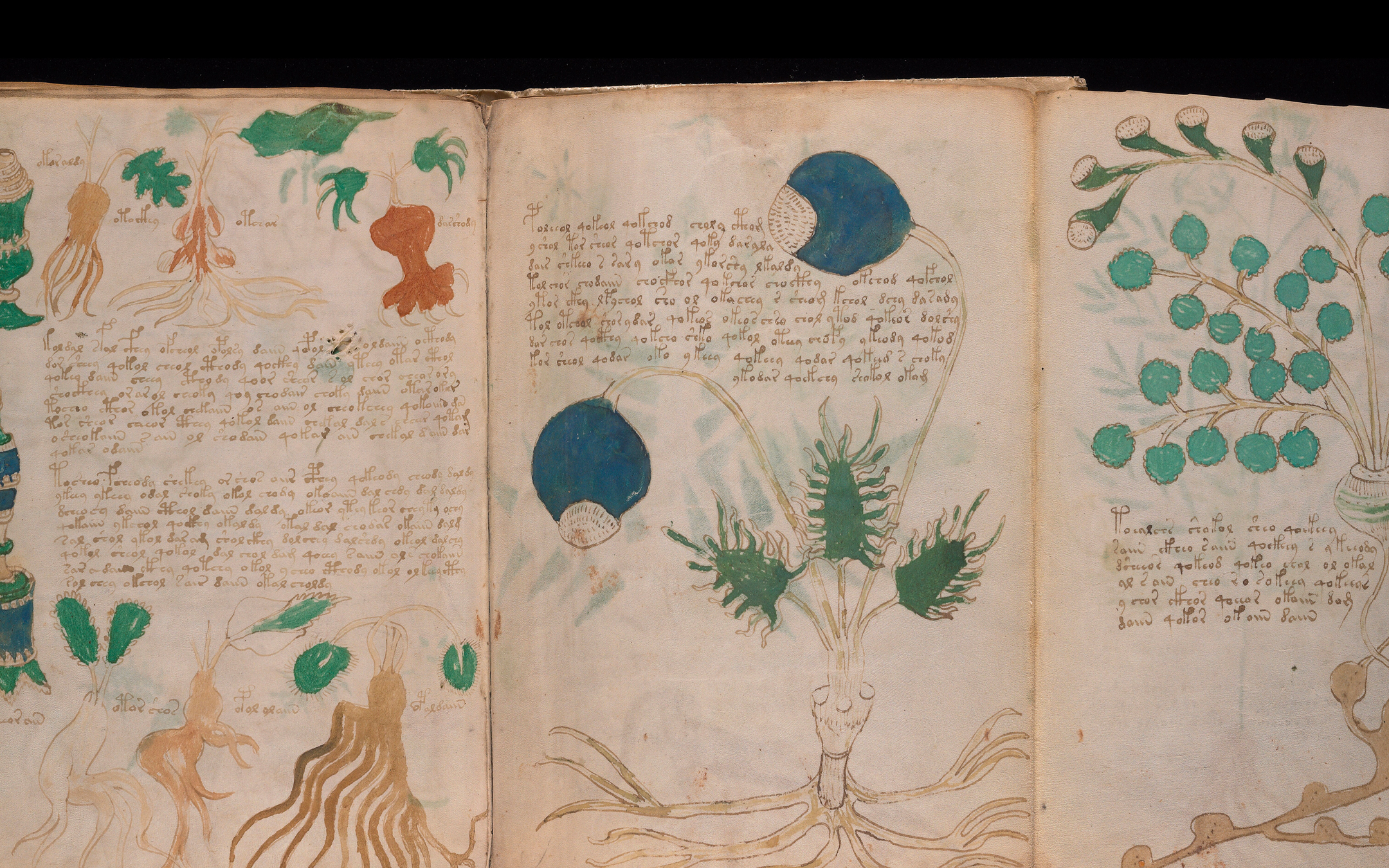

For now, our only insight into the manuscript’s probable content comes from its many illustrations, which reveal apparently themed sections.

The largest part, often referred to as the herbal section, is dedicated to drawings of puzzling plants, some with bizarre features: balloon-shaped human heads grow from one plant; certain roots bear a vague resemblance to animals; and a tiny green dragon sits beside another plant, seemingly inhaling or exhaling its leaves.

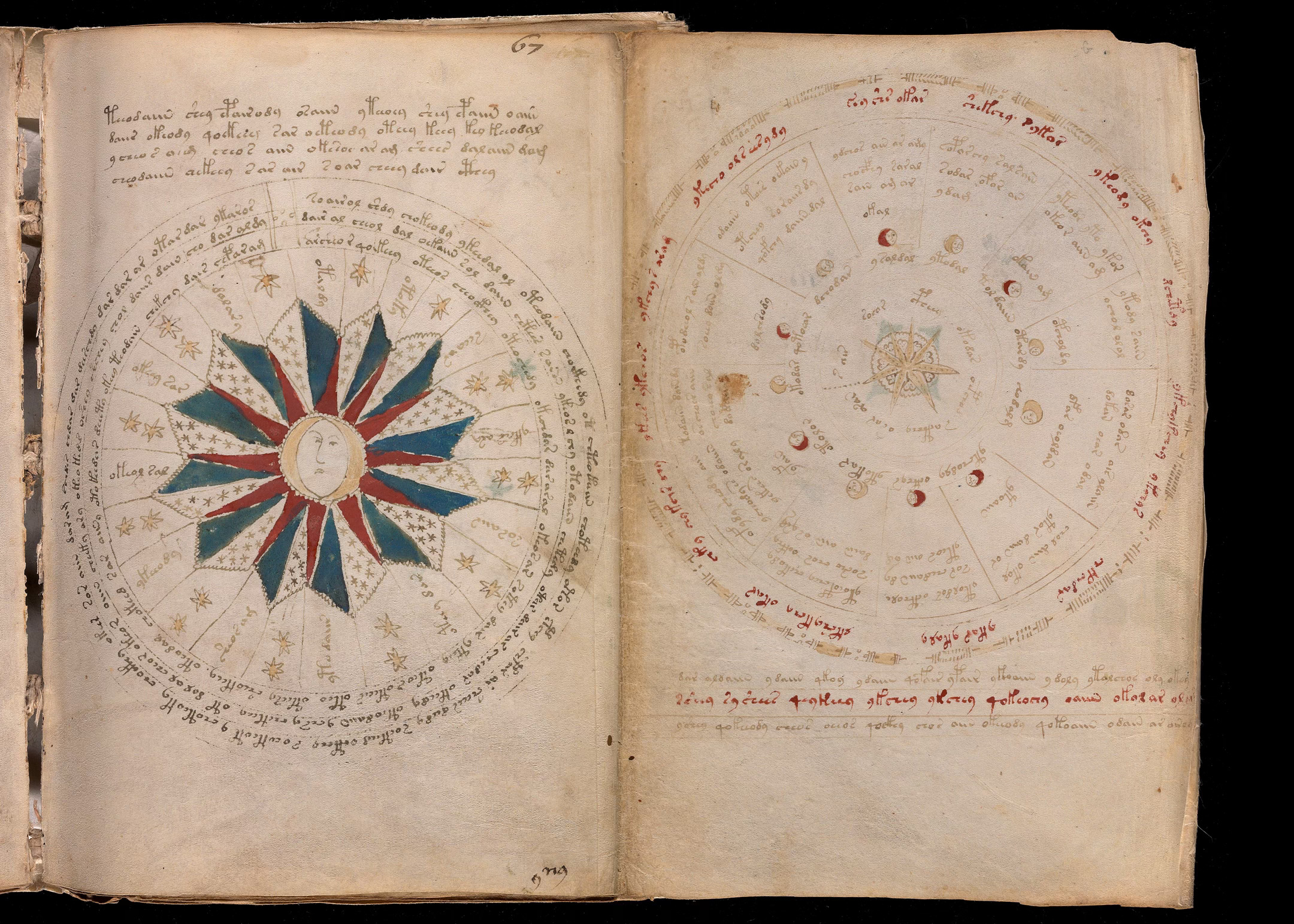

The next section appears to be dedicated to astrology, cosmology, and astronomy; the reader finds spirals and circles, signs of the zodiac, stars and moons, and nude women, standing or sitting in barrels, which are arranged in circles.

Afterwards, there is the bathing section. Here, naked women stand in green or blue pools of water, sometimes alongside unusual beasts, including a giant fish and a four-legged creature with a long snout.

A fold-out section follows, consisting of nine large connected circles, bearing ramparts, towers, bridges, turrets and tubes. Labels give it the appearance of a map.

Next is the pharmaceutical section; ornate pots in red and blue stand in rows beside plants, thought to be the ingredients for medical concoctions. A final section lacks illustrations, but appears to be a list of recipes, each introduced by a star.

The Discovery

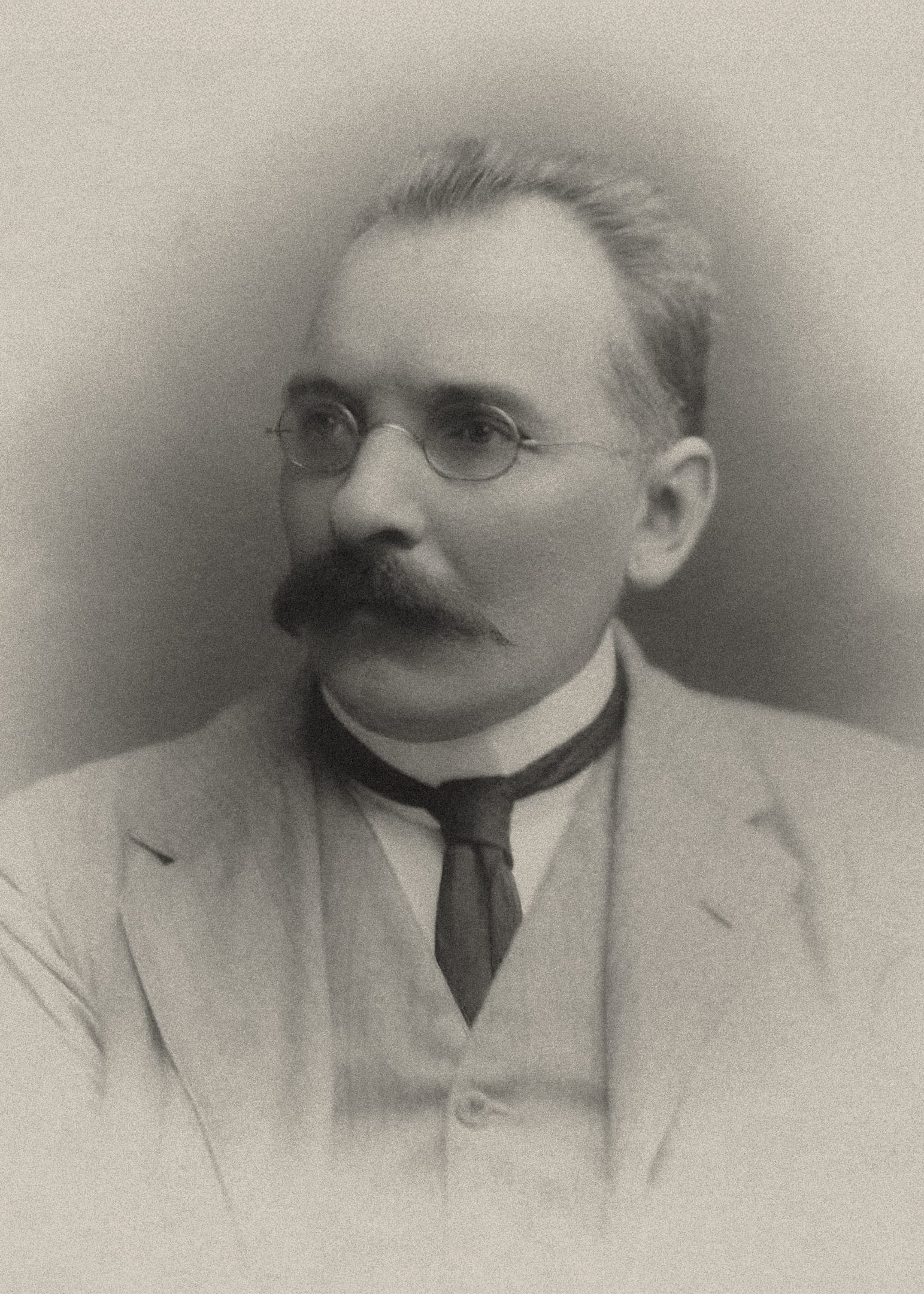

Since its discovery by the book dealer Wilfrid Voynich in 1912, researchers have pored over the manuscript’s pages in search of clues that might help them to explain its unusual content – a difficult task, given that even Voynich’s account of discovering the manuscript has its own mysteries.

In an article, Voynich explained that he found the manuscript in a chest in an ancient castle in southern Europe, calling his unexpected discovery an “ugly duckling.”

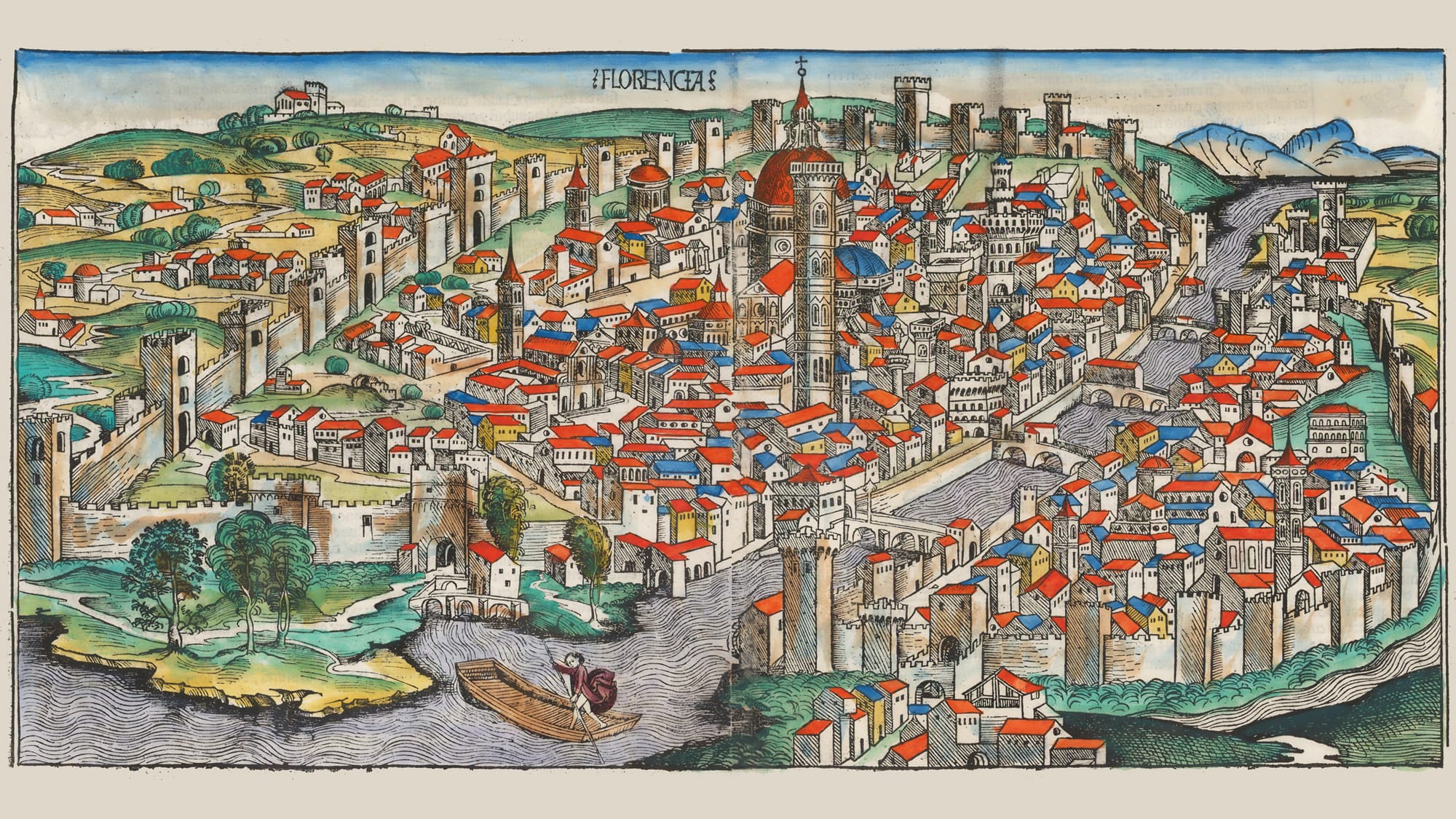

Years later, in a letter marked only to be opened after her death, Voynich’s wife, Ethel, added that the location was in fact Italy, and that the intermediary in the sale had been a Jesuit called Father Strickland.

For decades it was commonly believed that Voynich made his discovery in Villa Mondragone, in Frascati, outside of Rome, but recent research has revealed that it was more likely to be Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo. This is where the Jesuits hid many of their manuscripts from the Italian government, which, in the late nineteenth century, had tried to confiscate their documents and manuscripts for their planned national library.

In the decades after his discovery, Voynich failed to sell the manuscript, probably because of his hefty asking price – a massive $100,000. And so, after Voynich’s death in 1930, and the manuscript passing through various hands, it was given to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 1969.

The Voynich Manuscript’s Early History

A letter, found by Voynich with the manuscript, has long provided the only firm evidence for its early chain of ownership. This explains that the manuscript once belonged to the melancholy Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, who ruled from 1576 to 1612. He bought it for 600 ducats – gold coins – but there is no information regarding from whom or when.

Voynich speculated that Rudolf had bought it from the Elizabethan polymath John Dee, who lived in Prague in the 1580s, but there’s no evidence that Dee ever handled the manuscript, or even knew of its existence.

Now, thanks to recent research, it appears that the seller might have been the physician and alchemist Carl Widemann, who lived in Augsburg, Germany, in the late sixteenth century. Widemann had a side-business as a book dealer to rich clients, and among Rudolf’s imperial account records, there is only one case of him paying 600 gold coins for rare books. This was to Widemann in 1599.

Intriguingly, Widemann’s predecessor as city physician of Augsburg was the botanist and traveller Leonhard Rauwolf (1535-1596). Given Rauwolf’s interest in plants and herbal medicine, he is a good contender as a possible earlier owner.

Whatever the case may be, the manuscript passed from Emperor Rudolf to the royal physician Jacobus Horčický, who wrote his name and title on its pages. It is next found in the hands of the alchemist and legal scribe Georgius Barschius, who gave it to his friend, the physician and natural philosopher Johannes Marcus Marci.

It was Marci who, in 1665, wrote the letter that Voynich found with the manuscript, explaining its earlier history. Unable to make much progress deciphering its contents, Marci decided to send the manuscript, along with his letter, to the renowned Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in Rome.

Kircher had a great interest in world languages, and had even attempted to crack ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Nonetheless, he was unable to reveal the manuscript’s secrets. After Kircher’s death in 1680, it remained in one of the Jesuit libraries for the centuries that followed, until its (re)discovery in Villa Torlonia by Voynich.

Ongoing Research

Voynich and the manuscript’s first researchers believed its unusual writing to be a cipher, but failed to decrypt its content. Others suggested that it was an artificial language and script, or possibly a hoax.

Even today, although people claim (with great regularity) to have translated its symbols, none of their solutions have been widely accepted by the academic community. And, although some recent studies of the manuscript’s writing structure suggest that a pattern exists behind its characters (implying the presence of a true language), others have concluded the opposite, arguing that it is simply gibberish.

This may all sound bleak, but there have still been exciting and important discoveries over recent years. A study of the manuscript’s handwriting, published in 2020, revealed that five scribes worked together to produce its content, providing a valuable insight into its creation.

The scribes collaborated on the herbal section, probably due to its length; one copied out the astrological, astronomical, and cosmological content; and another was responsible for the bathing section. Two wrote the recipes section. Furthermore, radiocarbon dating has revealed that the Voynich Manuscript was produced between 1404 and 1438, placing its creation in an early fifteenth century context.

Other clues have helped researchers to locate the manuscript’s probable place of production. A drawing of a tiny castle bears swallowtail (also called Ghibelline) merlons, a feature of castles built around Verona. An archer, shown on the astrological page for Sagittarius, wears a Florentine hat.

The symbols that form “Voynichese” resemble those used in north Italian ciphers, shorthand, and astrological symbols; while the section dedicated to plants bears similarities to the illustrations found in alchemical herbals – manuscripts produced in northern Italy during the early fifteenth century.

Manuscripts on medicinal bathing and bath houses were also popular in this region during this time. Taken together, such clues suggest a northern Italian origin for the Voynich Manuscript, and fit well with the dates revealed by radiocarbon dating.

Given the available information, and based on the Voynich Manuscript’s illustrations, it would appear to be (or at least to imitate) a medical treatise, of the type used by physicians to choose the best plant roots and timings to cure their patients, perhaps with a focus on medicinal bathing.

But if this is the case, why would someone wish to encipher its content, if indeed it is enciphered? Why did five scribes work together to create it? And why did they use an expensive material like parchment, when paper was much cheaper? Could its writing be an artificial script and language, as some have suggested – or could the Voynich Manuscript be nothing more than a late-medieval hoax?

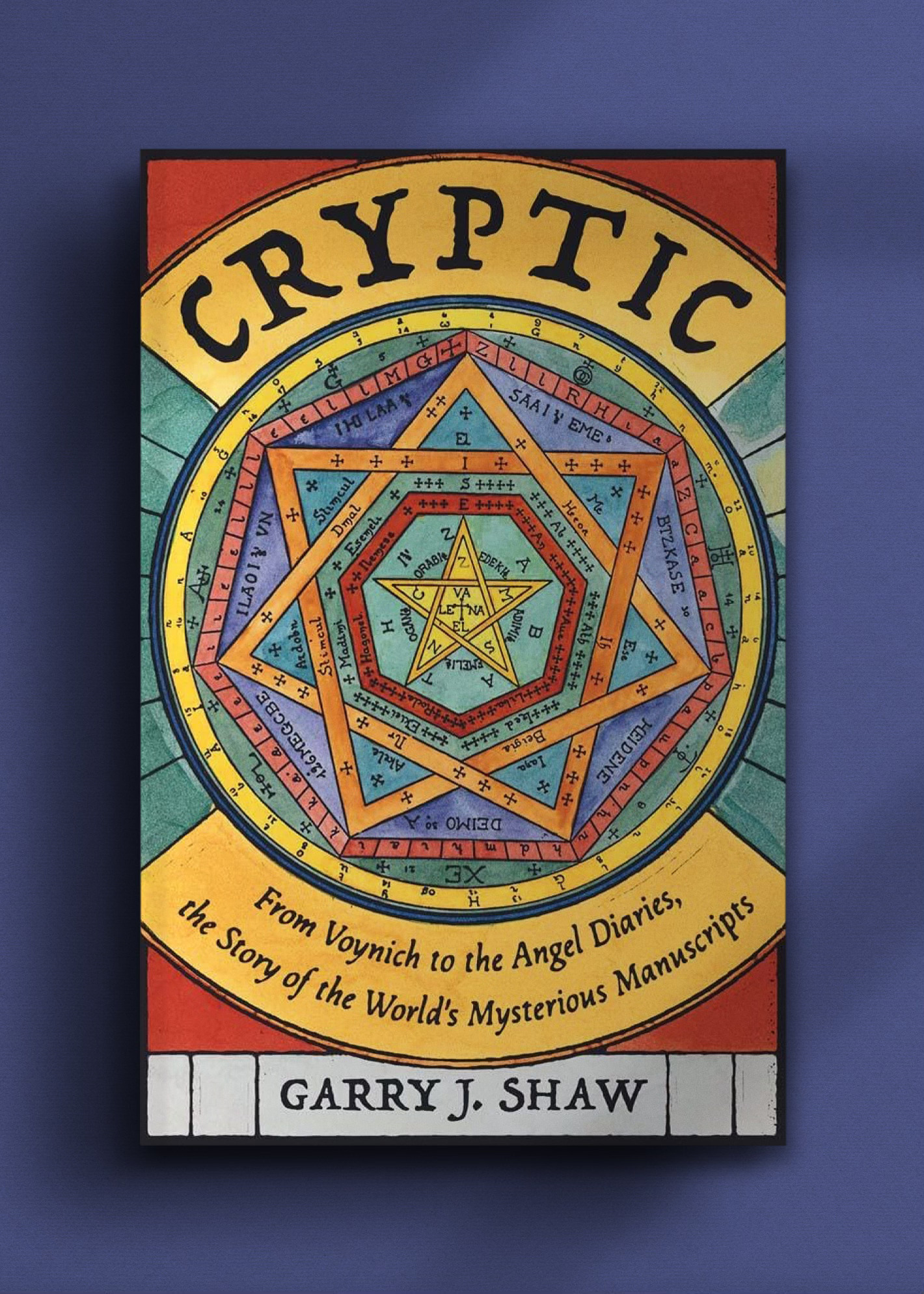

My own suggested answers to these questions are revealed in the final chapter of my new book Cryptic, From Voynich to the Angel Diaries, The Story of the World’s Mysterious Manuscripts, published by Yale University Press on 27 May 2025 •

This feature was originally published May 28, 2025.

Cryptic - From Voynich to the Angel Diaries, the Story of the World's Mysterious Manuscripts

Yale University Press, 27 May, 2025

RRP: £25 | 352 pages | ISBN: 978-0300266511

An absorbing history of Europe’s nine most puzzling texts, including the biggest mystery of all: the Voynich Manuscript.

Books can change the world. They can influence, entertain, transport, and enlighten. But across the centuries, authors have disguised their work with codes and ciphers, secret scripts and magical signs. What made these authors decide to keep their writings secret? What were they trying to hide?

Garry J. Shaw tells the stories of nine puzzling European texts. Shaw explores the unknown alphabet of the nun Hildegard of Bingen; the enciphered manuscripts of the prank-loving physician Giovanni Fontana; and the angel communications of the polymath John Dee. Along the way, we discover how the pioneers of science and medicine concealed their work, encounter demon magic and secret societies, and delve into the intricate symbolism of alchemists searching for the Philosopher’s Stone.

This highly enjoyable account takes readers on a fascinating journey through Europe’s most cryptic writings—and attempts to shed new light on the biggest mystery of all: the Voynich Manuscript.

“A richly illustrated guide that deftly leads you through a maze of historical mysteries, from angelic language to alchemical secrets. This 'Meetings with Mysterious Manuscripts' will take you down so many deeply intriguing rabbit holes that you might not find your way back to the daylight”

— Edward Brooke-Hitching, author of The Most Interesting Book in the World

With thanks to Heather Nathan.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store