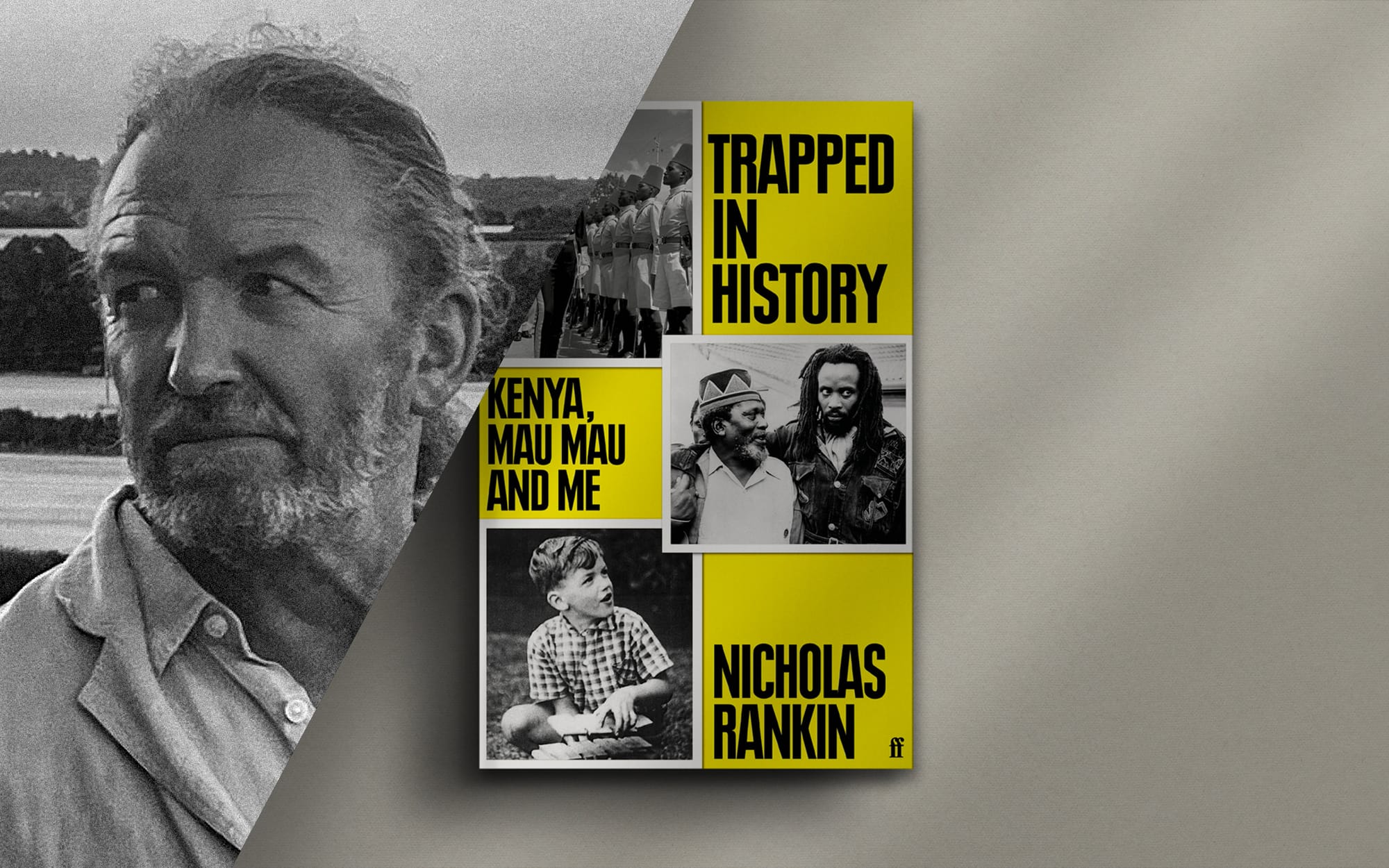

Trapped in History with Nicholas Rankin

Nicholas Rankin reflects on a childhood in Kenya

In 1954 Nicholas Rankin’s family left England for Kenya. As they sailed through the Suez Canal and southward along the African coast, drab, post-war Britain disappeared behind them. Ahead a new adventure awaited in an unknown land. Rankin would soon be enchanted with the natural beauty and rich culture he encountered.

But Kenya, in 1954, was no benign place. It was a fraught and contested country, struggling to free itself from colonial rule. Now, seven decades on, Rankin has returned to the events of his childhood. Trapped in History: Kenya, Mau Mau and Me is both a history and a memoir, of a writer who witnessed first-hand the end of Empire in Africa.

Unseen Histories

Trapped in History is an intensely personal book. You explain at the outset that the story – of your childhood in Kenya and of the accompanying colonial history – is one that you have long avoided. What draws you back to it now?

Nicholas Rankin

It's inevitable, as you age, that you find yourself looking back. In your sixties and seventies, you have much more past than future. You realise your own life is becoming history. You see the toys you once played with are now exhibits in the Museum of Childhood. You are a visitor from the past. And you can see your life's trajectory more clearly and you think about what made you who you are. You realise that a colonial boyhood in a foreign land is unusual. And because I am a writer, I think I ought to explore that and deal with it, before I die and everything I know vanishes. Of course, the child of back then was ignorant, but the grown man of today has a duty not to be ignorant, so that sets up a cross-current.

Unseen Histories

It is a book of many voices. One of the most intriguing perspectives comes from you, as a boy, looking out at Kenya in the 1950s. There’s a joyful description, for instance, of your house and gardens and the expansive view that you’ve extracted from your school books. Did Kenya really seem an idyll at the time?

Nicholas Rankin

It's important to understand that Kenya is a really beautiful country with an incredible variety of terrain and peoples, with a rich biota. We lived in the highlands, northwest of Nairobi, in the tea-growing area of Kiambu. It was about 6000 feet above sea level. The mornings were misty, you needed a fire at night because it was chilly, though the days could be lovely and warm. You were too high for mosquitoes and the stars - including the Southern Cross - shone brighter at night. Being outside in the sunny garden was paradisal. There was a sense of space for the innocent animal to play in. But of course, there are snakes in the garden of Eden.

Unseen Histories

1954 is an important year in your story. It is the year that your family sailed for Kenya but also a year of growing civil unrest in the country. Can you tell us about the ‘Emergency’?

Nicholas Rankin

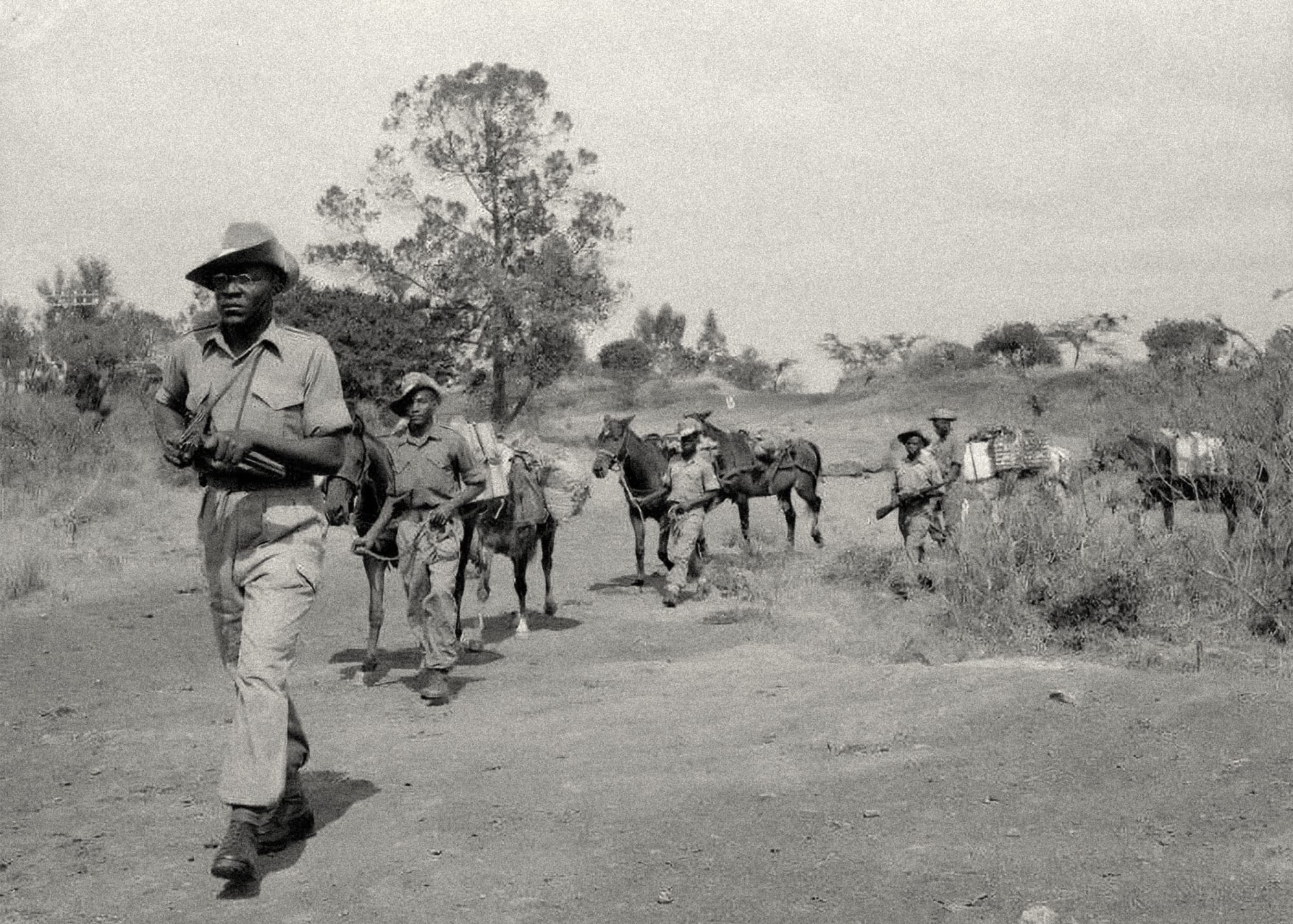

My personal story is braided into two major strands of history, which we could short-hand as the white and the black. The first is the European colonial project - conquest, settlement, development etc - and the second is the African reaction and resistance to sudden change, and the rise of African nationalism, the longing for independence from foreign, colonial rule.

Kenya Colony in the early 1950s was a pyramid of dominance with 50,000 Europeans above 200,000 Asians and five million Africans. The constitutional system wasn't flexible or porous enough to allow pressure from below - caused by land grievances and social injustices - to escape, so there was an explosion. Young radicals in a secret society which came to be known as Mau Mau started murdering servants of the colonial state, which then cracked down hard on 'terrorists'. The 'Emergency' declared by Governor Baring in October 1952 enabled draconian new laws and repressive measures, including mass detention without trial, the use of capital punishment (more than 1000 Africans were hanged) and summoning the British Army and the Royal Air Force in support of the civil power. It was 'a dirty war' which, for legal reasons, was deemed 'a civil disturbance'. This State of Emergency lasted until 1960.

I started this historical autobiography six years ago, at the end of 2017. And I did not go back to Kenya while writing it. Trapped in History is deliberately not a travel book. I call it somewhere in the text 'a papier-mâché memory palace'. — Nicholas Rankin

Unseen Histories

A deeply symbolic moment seems to happen on 26 May 1954, just after your arrival, when the Mau Mau burned a site called ‘Treetops’ down to the ground. Can you tell us about the significance of this?

Nicholas Rankin

Beautiful Kenya has been a tourist destination for over a century. 'Treetops' was a great visitor attraction of the Outspan Hotel in Nyeri. By a salt lick and waterhole in the Aberdare Mountains, the hotel owners had built a comfortable treehouse in the branches of a stand of giant mugumo fig trees, often considered sacred by the Kikuyu people, so that their hotel guests could safely watch and photograph the wild animals by day and night.

In February 1952, Princess Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of King George VI (who had shot rhino and other big game in Kenya on his own safari in 1925) was staying at Treetops with her husband the Duke of Edinburgh, watching elephants. That night in Africa, she became Queen. Prince Philip broke the news of the King's death to her at Sagana Royal Lodge, a house and garden on the slopes of Mount Kenya, a gift from Kenya Colony. The world-wide Commonwealth tour was now cut short and Queen Elizabeth II flew back, in mourning black, to London. So, as part their armed uprising against British rule, the Mau Mau guerrillas (or itungati) of the Kenya Land Freedom Army were quite deliberate in burning down Treetops because they thought the grove had been profaned by the foreign monarch.

Unseen Histories

As in Alex Renton’s recent book, Blood Legacy, you find evidence of slave ownership in your family. Yours is on a much small scale than Renton’s, but it does prompt a similar response. ‘It can’t be guilt in the sense of remorse for some crime I committed myself’, you write, ‘though there is communal shame in acknowledging an injustice of long ago’. Can you explain a little more about this?

Nicholas Rankin

Our feelings about the past are necessarily complicated. I think I am patriotic in that I love my country and its culture, but that does not mean I can't acknowledge the wrongs of the past and the destruction my nation has wrought in its long history. That's true of my own family as well. Now, there's an interesting anthropological/cultural debate to be had about Western guilt versus Eastern shame, but at this moment the discussion of British slave-ownership in the past is very much tied into the question of apologies and reparations. The conservative/Daily Mail anxiety seems to be that any form of apology for the sins of the fathers will trigger claims for enormous financial reparations, so it's better never to say sorry. That may well be sound legal advice, but it does not sit well with the human heart. I think it might be a good idea to say sorry more often. The conversation about the legacies of the British Empire will last as long as the history is contested.

Unseen Histories

One of the many intriguing colonial characters you write about is Joseph Thomson – who today is memorialised in Thomson's gazelle. Can you tell us about his early expeditions?

Nicholas Rankin

Joseph Thomson (1858-1895) is an attractive person: a young Christian Scot who - unlike many other European explorers - did not kill anyone on his six journeys through uncharted Africa. Thomson's traveller's motto was Italian: Chi va piano va sano, chi va sano va lontano. 'He who goes gently goes safely; he who goes safely goes far.' Thomson explored East and West Africa as well as Morocco. I believe his Royal Geographical Society lecture and subsequent book Across Masailand greatly influenced Rider Haggard's famous 1885 novel of imperial adventure King Solomon's Mines.

Unseen Histories

Thomson’s expeditions, in the grand scheme of history, were not long ago. He was only working in the 1880s and Nairobi, today’s Kenyan capital, was only established in 1899. As a young boy did you have a sense of how young and oddly formed a country Kenya was?

Nicholas Rankin

Kenya is both very young and very old. Nairobi, the capital, was barely fifty years old when I first saw it. And yet the discoveries of the palaeontologists Louis and Mary Leakey, in the Coryndon Museum and out at Olduvai Gorge, were pushing back human origins millions of years. In geological terms, the white presence in Kenya is just a thin smear in the great cliff of time. My family and I lived in a modern world - hot water, fridges, telephones, motor cars, radios etc - but then you saw pastoral Maasai with blankets and spears herding their cattle who lived in a premodern world. The oldest buildings you ever saw in Kenya were medieval Arab ruins overgrown with jungle at places like Gedi on the Indian Ocean coast. You had to see very old places in England to begin to understand how very new all the buildings and infrastructure of colonial Kenya were.

Unseen Histories

The Mau Mau uprising was a very present event in your childhood. You state that, shortly before your arrival, they had been a deadly skirmish at the nearby Brackenhurst Hotel. How did you find the experience of going back and researching the history afresh all of these years later?

Nicholas Rankin

I started this historical autobiography six years ago, at the end of 2017. And I did not go back to Kenya while writing it. Trapped in History is deliberately not a travel book. I call it somewhere in the text 'a papier-mâché memory palace'. The research involved personal remembering as well as reading many books, articles and academic papers, perusing old newspapers and re-viewing old films and photographs. It was a huge learning process for me, finding out lots of things that I had not previously known or thought about. There is much discovery in digging over a field of battle, but also great disquiet. Going back into the troubled past was not easy for me. Some of the processing of atrocity and torture went on during the isolation of COVID lockdowns and was quite painful. The book is an attempt to explain rather than excuse and tries to be fair. John Lonsdale called it 'a self-searching exorcism of empire' and that seems right to me. 𖡹

Trapped in History: Kenya, Mau Mau and Me

Faber & Faber, 16 November, 2023

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-0300276091

"An unforgettable mix of history and memoir"

– The Guardian

Trapped in History tells how the British colonised Kenya and how African nationalism arose under Jomo Kenyatta. It describes the terrifying first attacks by the guerrilla freedom fighters known as Mau Mau.

Though defeated, the Mau Mau hastened the end of British rule in Kenya. Trapped in History explores the effect the uprising on the author, who grew up as a child in the Kenya colony. The book is both a history, as well as a memoir, of the end of Empire.

"A detailed, dramatic and deeply human view of Kenya in the post-war era"

– The Telegraph

"Immensely readable"

- Literary Review

With thanks to Tara McEvoy