Travel in Old Japan

Japan in the Age of the Shoguns was a dynamic place, full of colour, energy and movement. Here Lesley Downer takes us for a trip on its old roads

Travelling around Japan in olden times was complicated by the shoguns' prohibition of wheeled transport, excepting the carts that were used to carry goods.

This meant that ordinary people, like the seventeenth-century poet, Matsuo Basho, were obliged to walk or make use of palaquins or some other colourful contraption.

In this piece Lesley Downer, an expert of Japanese culture and history and the author of The Shortest History of Japan and On the Narrow Road to the Deep North, explains how an advanced society sought to move without wheels.

This year, the second year of Genroku, I have decided to make a long walking trip to the distant provinces of the far north ...’

On 16 May 1689 the poet Matsuo Basho set off for the north of Japan. He recorded his journey in a travel diary of prose interspersed with haiku, seventeen syllable poems, which he named The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

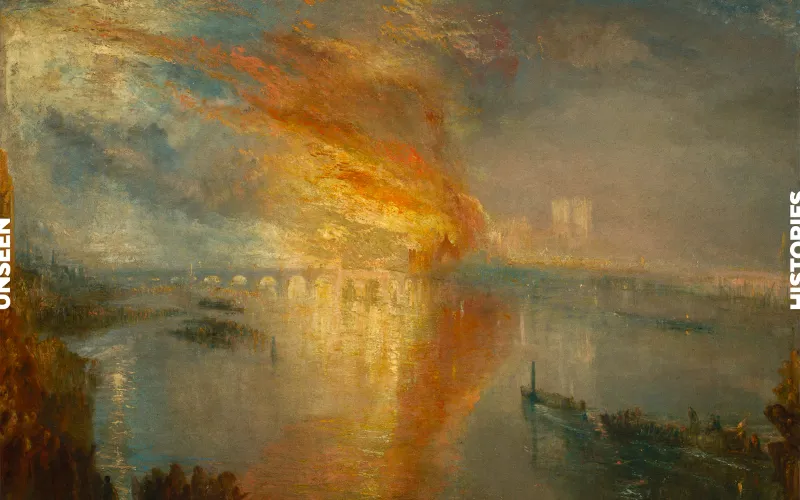

Fire was a commonplace hazard in nineteenth-century London. Although much had changed since the days of the Great Fire of 1666, when much of the capital was constructed from combustible materials, people continued to live at close quarters with candles still a common method of illumination.

A fire at the Houses of Parliament, though, was a terrible prospect. Inside the Lords, behind the door that Cottle had recently pushed closed, the flames continued to spread. As they did so they progressed towards artefacts of immense cultural value. The most notable object—one that was dwelt upon by many newspapers in the aftermath—was a celebrated sixteenth-century tapestry, which portrayed in vivid and thrilling detail the defeat of the Spanish Armada. Each section of the tapestry was kept inside a wooden frame.

Then, not far away, was 'St Stephen's Chapel'. The chamber of the House of Commons retained the form of a choir. Six rows of wooden benches, covered with green cloth, rose up at either side of the Clerks' Table and the Speaker's Chair. The whole room was lined with oak.

At seven o'clock the fire was clearly visible from the streets outside. By now 'detachments of police'—still a novelty themselves—were present at the scene, as were 'engines from the different fire-stations.'

The Morning Chronicle took up the story:

Friday 17 October 1834

'Immense crowds of people at the same time assembled, and filled up the different avenues to the building. At first there was a deficiency of water; but a supply was soon procured, and the firemen made the utmost exertions to get the fire under; but it had already gained such strength, that their efforts appeared to have little effect.

Unfortunately, too, there was a considerable wind from the south-west. In a very short time after the commencement of the fire, strong detachments of the first regiment of the Grenadier Guards and of the Coldstream Guards marched to the spot and with the assistance of the police, kept an open space before the building, so as to allow the firemen to work without impediment.

Lord Melbourne soon arrived, along with several other Noblemen; and Mr Gregorie, the magistrate of Queen-Square, sent off the whole officers of that establishment to render every assistance in their power.

By half past seven the flames had completely gutted the interior of the building, with the exception of the Parliament office; and in a few minutes afterwards the roof fell in with a tremendous crash.

The fire, the fierceness of which was heightened by the increasing freshness of the breeze, then communicated itself to the House of Commons, and the whole range of buildings was soon wrapped in one blaze.

The scene at this time was grand and terrific. The flames shot up to a great height, and obscured the light of the moon, increasing, rather than diminishing the apparent darkness of the night, and contrasting in a striking manner the brilliant light which they threw upon the surrounding objects, with the general blackness of the sky.

Not only the streets in the vicinity, but the different bridges were now covered with immense multitudes, gazing with mingled awe and admiration on the scene of destruction.

While many watched in horror as the buildings collapsed, others threw their energy into salvaging what they could. Inside the Houses of Parliament were public records that documented England's deepest past. The challenge of saving these was taken up by John Hobhouse, one of the first senior politicians to arrive on the scene.

Hobhouse issued an order that every effort be made for the 'immediate removal' of these papers, 'an operation which he actively and anxiously superintended'.

Those watching the fire from outside were now met with the sight of Hobhouses's frantic operation. Everything was requisitioned that could be of use: hackney carriages, coaches, cabs, waggons, hand carts.

Many of the records were thrown in heaps, through the doors of private homes in the nearby streets. Others were carried with more decorum to governmental offices. Hobhouse would receive great credit for his actions on the night, but the salvaging of so many papers of such historical significance was also due to the selfless application of the firemen. Many of them, ran one report, 'incurred great danger, but nothing could exceed their zeal and disregard of personal risk'.

With a fire so ferocious, there was every chance that lives would be lost through smoke inhalation or worse. One of the first and narrowest of escapes was that of 'Mrs Wright', the Housekeeper of the House of Lords, who was very nearly penned in her apartment by the advancing flames.

Lord Frederick FitzClarence, meanwhile, had been in one of the 'uppermost rooms'. FitzClarence was an army officer and an illegitimate son of King William IV and on the night of 16 October he was in a top floor room when the fire broke out.

He remained unaware of the danger until someone spied him through a window. His rescue was aided by a new piece of technology, 'the fireman's ladder'. This innovation, the London Chronicle explained, 'is formed of parts that slide on each other'. One of these was brought and erected outside his window. FitzClarence, the Chronicle reported, was 'the last who got upon the ladder'.

Friday 17 October 1834

At nine o’clock the whole of the three regiments of Guards were on the spot, under the command of Sir George Hill, Colonel Wood, Lord Butler, and Captain Davis. At ten the Royal House Guards (blue) arrived from the Regent’s Park barracks.

A part of the Foot Guards were nearly cut off at one time, while doing duty on one of the western turrets of the House of Commons. Some portion of the intermediate building fell and left them in a most precarious situation, surrounded by the flames. They were, however, providentially rescued by the application of fire-ladders.

At half-past ten most of the furniture of the Exchequer and other law courts had been removed to the pavement nearly opposite Poet’s Corner. At this time the fire, bursting through the places which had lately been windows, was blazing with fearful brilliancy.

About eleven the fire reached the Speaker’s House, which, in half an hour, was totally destroyed; but fortunately the valuable property which it contained had been previously removed.

By three o’clock this morning the fire was so much abated that no apprehensions remained of its extending further.

As the smoke rose over the wreckage in the morning, Londoners were left with the dismal prospect of a lost landmark. Seventy three Parliaments had sat in the destroyed buildings since the accession of King Henry VIII in 1509.

Gone was the place where Lord Chancellor Clarendon was impeached in 1667; gone was the chamber where Matthew Prior had stood in 1715 on charges of high treason; gone was the House of Commons in which the MP John Wilkes had been declared an outlaw in 1764.

Extent of Damage Done

The following is the official report upon the damage done to the buildings, furniture, etc. of the two Houses of Parliament, the Speaker’s Official Residence, the official residence of the Clerk of the House of Commons, and to the Courts of Law at Westminster Hall.

17 October 1834

House of Peers

The House Robin Room, Committee Rooms in the west front, and the rooms of the resident officers, as far as the Octogon Tower at the south end of the building — totally destroyed.

The Painted Chamber — totally destroyed.

The north end of the Royal Gallery, abutting on the Painted Chamber — destroyed from the door leading into the Painted Chamber, as far as the first compartment.

The Library and the adjoining rooms, which are now undergoing alternation as well as the Parliament Offices and the Offices of the Lord Great Chamberlain — saved.

House of Commons

The House, Libraries, Committee Rooms, Housekeeper’s Apartments &c are totally destroyed (excepting the Committee Rooms Nos. 11, 12, 13 and 14, which are capable of being repaired).

The official residence of Mr Lay, clerk of the house, is totally destroyed.

The official residence of the Speaker, The State Dining Room, under the House of Commons is much damaged but capable of repair.

All the rooms from the oriel window to the south side of the House of Commons are destroyed.

The Levee Rooms and other parts of the building, together with the public galleries and part of the Cloisters, very much destroyed.

The furniture, fixtures, and fittings to both Houses of Lords and Commons, with the committee rooms belonging thereto, is with few exceptions destroyed. The public furniture at the Speaker’s is in great part destroyed.

Opinions Respecting the Cause of the Fire

Naturally, pinpointing the cause of the fire was a central concern for the newspapers in the days immediately afterwards.

There was so much conjecture that The Morning Herald cautioned, 'the mystery which hangs over the destruction of the two houses of parliament is not yet cleared up. Any statement as to whether it was the result of accident or design must yet be premature, because the confusion attendant upon the calamitous event, and the necessity of making unceasing efforts to get the flames completely under, afforded no time or opportunity, in fact, for deliberate investigation of the cause.'

One theory though, was printed in the Globe and Courier. It were said to be 'very extraordinary, if true'.

A correspondent says that the fire is stated to have originated from the negligence of the persons employed in destroying the 'tallies', pieces of wood which contained the modes of reckoning by notches, carved on the edges, which plan has existed since the time of the Saxons.

They were burning them by placing piles of them upon and overloading a fire, in a grate of a room situate nearly over Bellamy’s coffee-rooms, and which communicated to the wood-work. The closest inquiry is at present in progress.

This account of the origin of the fire is corroborated by another correspondent, who states ... the men appointed to the duty growing impatient, from the slow manner in which they were consumed, thrust the whole into the grate, which formed a large pile, the flames of which rushed with great violence and heat up the chimney.

In a few minutes the whole was a blaze of fire, which rushed from the flues, and set the apartments in one body of fire.

The Day Parliament Burned Down by Caroline Shenton (Oxford University Press, 2013)