Travel in Old Japan

Japan in the Age of the Shoguns was a dynamic place, full of colour, energy and movement. Here Lesley Downer takes us for a trip on its old roads

Travelling around Japan in olden times was complicated by the shoguns' prohibition of wheeled transport, excepting the carts that were used to carry goods.

This meant that ordinary people, like the seventeenth-century poet, Matsuo Basho, were obliged to walk or make use of palaquins or some other colourful contraption.

In this piece Lesley Downer, an expert of Japanese culture and history and the author of The Shortest History of Japan and On the Narrow Road to the Deep North, explains how an advanced society sought to move without wheels.

Furyu-no Culture’s beginning:

hajime ya oku no Rice-planting song

ta-ue uta Of the far north

‘This year, the second year of Genroku, I have decided to make a long walking trip to the distant provinces of the far north ...’ On 16 May 1689 the poet Matsuo Basho set off for the north of Japan. He recorded his journey in a travel diary of prose interspersed with haiku, seventeen syllable poems, which he named The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

He travelled on foot, wearing the standard travellers’ garb of straw sandals and carrying a straw raincoat which, when he put it on, made him look like a walking haystack. He had to buy new straw sandals every few days because they wore out so quickly.

At the time Japan was ruled by shoguns who maintained order by banning all wheeled transport except for goods. Great folk rode in palanquins or more rarely on horseback but most people went on foot.

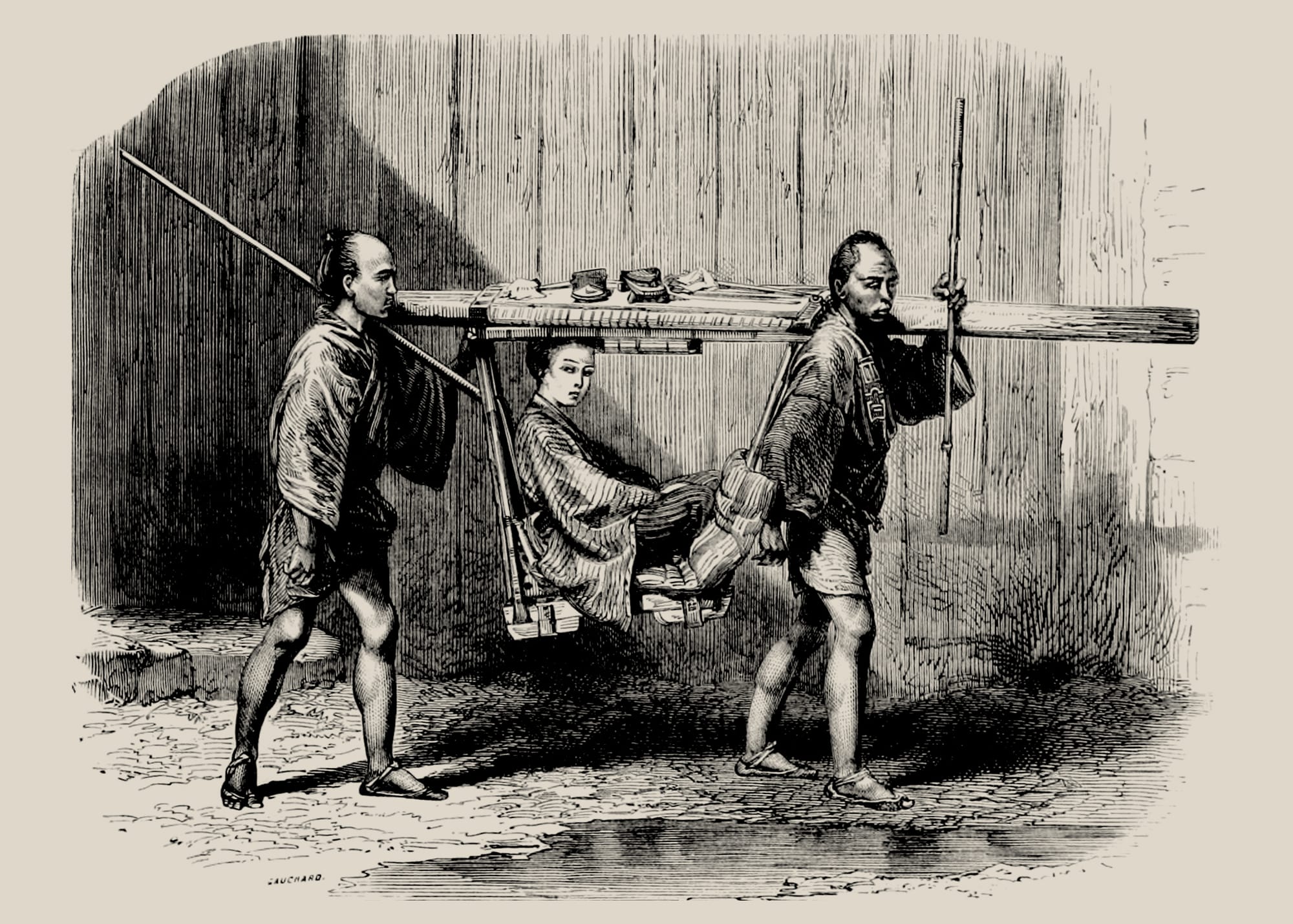

There were different sorts of palanquin. The grandest could be lacquered and beautifully decorated inside and out with pictures from The Tale of Genji on the walls and eight bearers all in livery. But it was still a small wooden box where you sat cross-legged or on your knees, freezing in winter and fanning yourself frantically in summer.

No matter how important you were, you’d be jogged along for hours in semi-darkness, tossed around as if you were in a ship at sea.

For more humble folk there were sedan chairs rather like a deckchair on two long bamboo poles, carried by two scrawny porters, which you could hire like a taxi.

At the time Japan was divided into 260 domains or princedoms, each ruled by a daimyo lord under the overall control of the shogun. Each domain was like a small country. As you crossed from one to the next you had to show your travel permit at the border post.

The main job of the border guards at the barriers closest to Edo, the shogun’s capital (now Tokyo), was to keep a keen eye out for weapons being smuggled in or women being smuggled out. They were equipped with long poles with a big hook at one end so they could grab a woman’s obi sash as she tried to sneak by.

To make sure the 260 lords didn’t have the time or funds to start a rebellion, they had to maintain up to three palaces in Edo as well as another palace in their own domain; and they were obliged to travel to Edo every year or two, stay a year or so, then go home again, a system known as ‘alternate attendance’ at the court of the shogun. They also had to leave their womenfolk and a whole household in Edo as hostages, which was why there was a danger of women sneaking out.

Lords spent a large part of their lives on the road. They travelled in style, accompanied by an enormous entourage - lords and ladies in their palanquins, squadrons of samurai, some on horseback, some on foot, court officials, ladies-in-waiting, accompanied by baggage masters on horseback, shoe bearers, parasol bearers, bearers of the lord’s bath and bathwater, bearers of food, chefs and bearers of tea-making equipment, adding up to several thousand in all.

There’d be thousands of locally hired porters to hump boxes and drag the huge wheeled trunks and grooms to lead the pack horses laden with luggage. It took 4 or 5 days for one of these vast processions to wend its way through any one village.

Each village had a honjin, like a five star hotel, where the lord could stay, with his retainers and servants in the servants’ quarters. His suite would be luxuriously turned out with silk-edged tatami matting, soft futons, an alcove with a hanging scroll and a vase of flowers and kitchens where his chefs prepared his meals.

He’d carry his own food but he’d also enquire after the specialities of the region and the innkeeper would be proud to serve them. There’d be a bath if he hadn’t brought his own and a garden with a pond where he could relax.

There were also lots of lodgings for ordinary folk, from wandering poets like Basho to swordsmen, mendicant monks, merchants keeping a close eye on the baggage train loaded with their goods and bands of pilgrims on their way to worship at a particularly holy Shinto shrine or Buddhist temple; as in Chaucer’s England, the best excuse for a holiday was to go on pilgrimage. Here they could eat, sleep and, if they wanted, engage the services of the local prostitutes.

There were five main highways, all bustling with people. The most famous was the Tōkaidō, the Eastern Sea Road (above), which ran along the coast from Edo to Kyoto, the official capital and the home of the emperor. It was kept neatly swept and planted with trees at precise intervals so you always knew how many ri (a bit less than 4 kilometres) you were from Edo.

There was an excellent trade in straw sandals and children would run out to collect horse and human manure for fertiliser. The road was punctuated with post towns, as depicted in Ando Hiroshige’s Fifty Three Stations of the Tōkaidō.

Travellers stopped off regularly to eat, rest and look at the sights.

Japan has a long history of travel and is rich with beautiful views, scenes celebrated in poetry, fields where famous battles were fought, Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. People would travel en masse to see the cherry blossom at Mount Yoshino in spring or the autumn leaves in Kiso or to take the waters at the many hot spring resorts which dotted the country.

Basho didn’t take the highways. As fact as the title of his travel diary makes clear, he deliberately took back roads. But these roads too would have been crowded with people, again like England in Chaucer’s time.

From the shogunate’s point of view the purpose of the whole exercise was to maintain tight control over the unruly populace and prevent any kind of uprising and in this they were successful for 250 years.

But the whole system took on a life of its own. The idea was to make travel difficult, to discourage people from travelling, but in fact people travelled probably more than their contemporaries in Europe.

And there were many rebellious spirits who found a way to get round the restrictions.

In a wonderful book called Musui’s Story: The Autobiography of a Tokugawa Samurai, the author, Katsu Kokichi (1802 - 1850) describes his reprobate life as a delinquent samurai and wrote about how when he came to a border post he never had the requisite travel pass.

He would either sneak around outside the post or bluster his way through, declaring with suitable bombast that he was a retainer in the service of Lord So-and-So, a completely fictitious but very grand-sounding lord, and threatening that Lord So-and-So would ensure the guards lost their jobs at the very least if they didn’t treat him with due respect.

As for Basho, his journey took him five months from spring into autumn, and he wrote about it in his legendary The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which is full of wonderful haiku like this:

kono michi ya This road!

yuku hito nashi ni With no one on it

aki no kure Autumn darkness falls

This feature was originally published October 1, 2024.

She has traveled widely and given lectures at the Japan Society New York, at Asia and Japan Societies across the United States, at the Royal Geographic Society and the British Museum in London, and many other venues.

She was the historical consultant for Northern Ballet’s spectacular 2020 ballet Geisha and she appears on Age of the Samurai: Battle for Japan (Netflix). Her acclaimed book, On the Narrow Road to the Deep North: Journey into a lost Japan, will be reissued by Eland Classic in paperback this November.

She lives in London with her husband, the author Arthur I. Miller.

The Shortest History of Japan

Old Street Publishing, 10 September, 2024

RRP: £9.99 | ISBN: 978-1913083922

“A terrific overview of Japan’s long and rich history that covers an astonishing amount of ground. A gem of a book that is as engaging as it is readable” – Peter Frankopan

Discover the aesthetic traditions, political resilience, and modern economic might of this singular island nation.

Zen, haiku, martial arts, sushi, anime, manga, film, video games . . . Japanese culture has long enriched our Western way of life. Yet from a Western perspective, Japan remains a remote island country that has long had a complicated relationship with the outside world.

Japan—an archipelago strung like a necklace around the Asian mainland—is considerably farther from Asia than Britain is from Europe. The sea has provided an effective barrier against invasion and enabled the culture to develop in unique ways. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shoguns successfully closed the country to the West. Then, Japan swung in the opposite direction, adopting Western culture wholesale. Both strategies enabled it to avoid colonization—and to retain its traditions and way of life.

A skilled storyteller and accurate historian, Lesley Downer presents the dramatic sweep of Japanese history and the larger-than-life individuals—from emperors descended from the Sun Goddess to warlords, samurai, merchants, court ladies, women warriors, geisha, and businessmen—who shaped this extraordinary modern society.

The Shortest History books deliver thousands of years of history in one riveting, fast-paced read.

“A delightful and illuminating read about Japan’s long history. Downer’s book covers prehistoric times through the present-day. This work has the rare quality of being both scholarly and approachable for the non-expert. . . . Essential reading for both general audiences and scholars who are interested in an engaging overview of Japan’s complex history”

― Library Journal, starred review

“Brisk, brilliant, and compulsively readable, Downer’s new history takes us from the ancient archipelago down to the vexed present day, via shamans, shoguns, ‘modern girls,’ and Super Mario. Highly recommended”

― Christopher Harding, author of A History of Modern Japan and The Light of Asia

With thanks to Old Street Publishing.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store