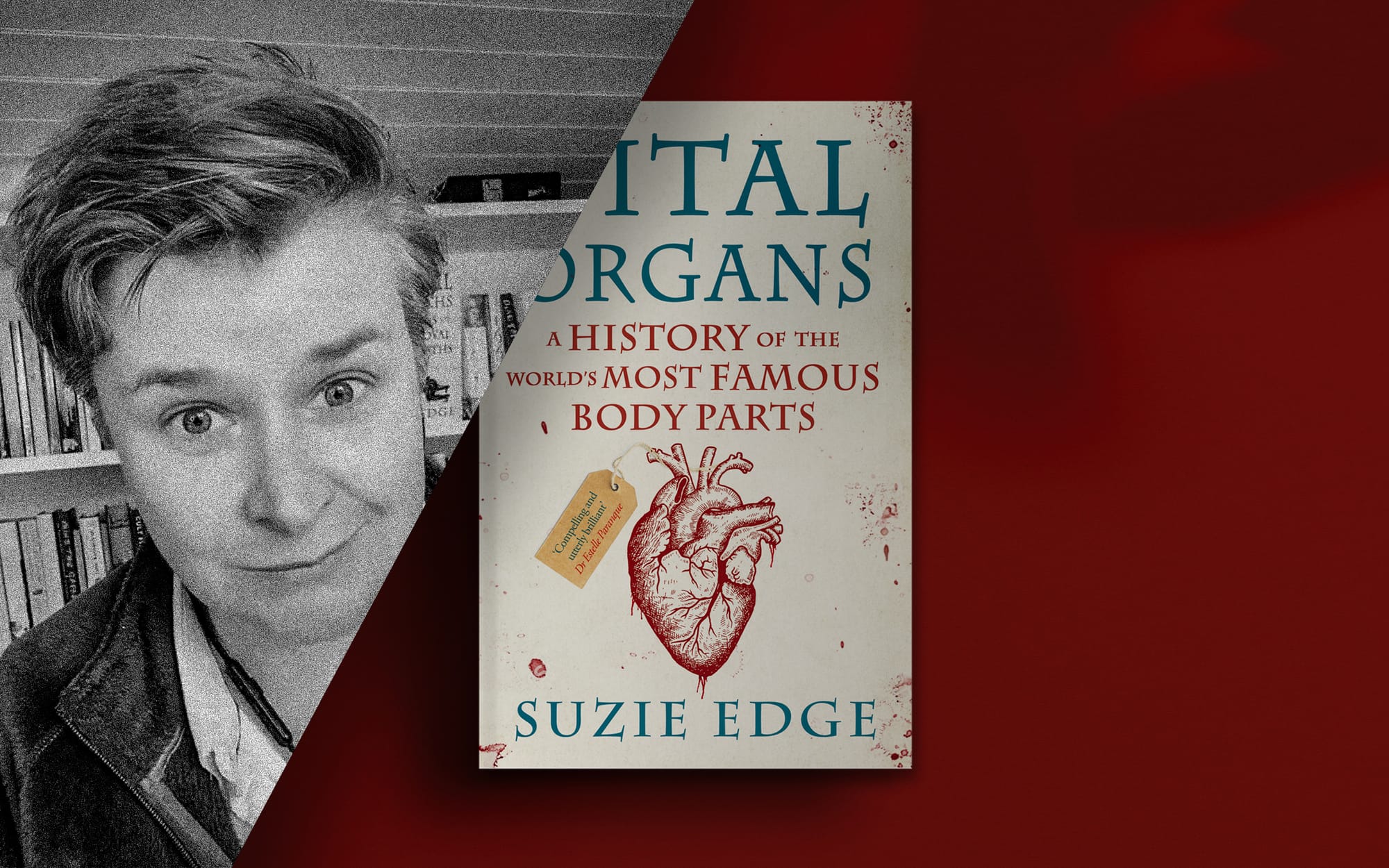

Vital Organs with Suzie Edge

Suzie Edge on the stories that come from within

The history of our species is long and varied. But while we live at ever increasing distances from figures like Queen Victoria, King Louis XIV or Alfred the Great, we are bound together by our shared physical experience of the human body.

In her new book, Vital Organs, Suzie Edge uses our body parts as a pathway into the past. Here she explains more about her motives and discoveries.

This interview is illustrated with graphic depictions of body parts.

Unseen Histories

Vital Organs ranges very widely. We read about characters from William Shakespeare to Dwight Eisenhower, and about body parts from skulls to stomachs. How did you select your material?

Suzie Edge

Perhaps surprisingly there were so many wonderful stories involving body parts in history. Some were meatier than others but mostly I tried to vary the stories where there might be different interests and tales from different parts of the world. Some stories I found were no more than a line or anecdote or a suggestion by an academic that was never backed up, so those stories didn’t make it into Vital Organs. When considering how to present the stories I decided to do what I knew well from my work as a doctor, examining the body from head to toe.

Unseen Histories

Often your chapters will start with a memorable anecdote, like the slicing off of the astronomer Tycho Brahe’s nose, before you step back to evaluate the science and the evidence. How many of these stories did you know before you began the research?

Suzie Edge

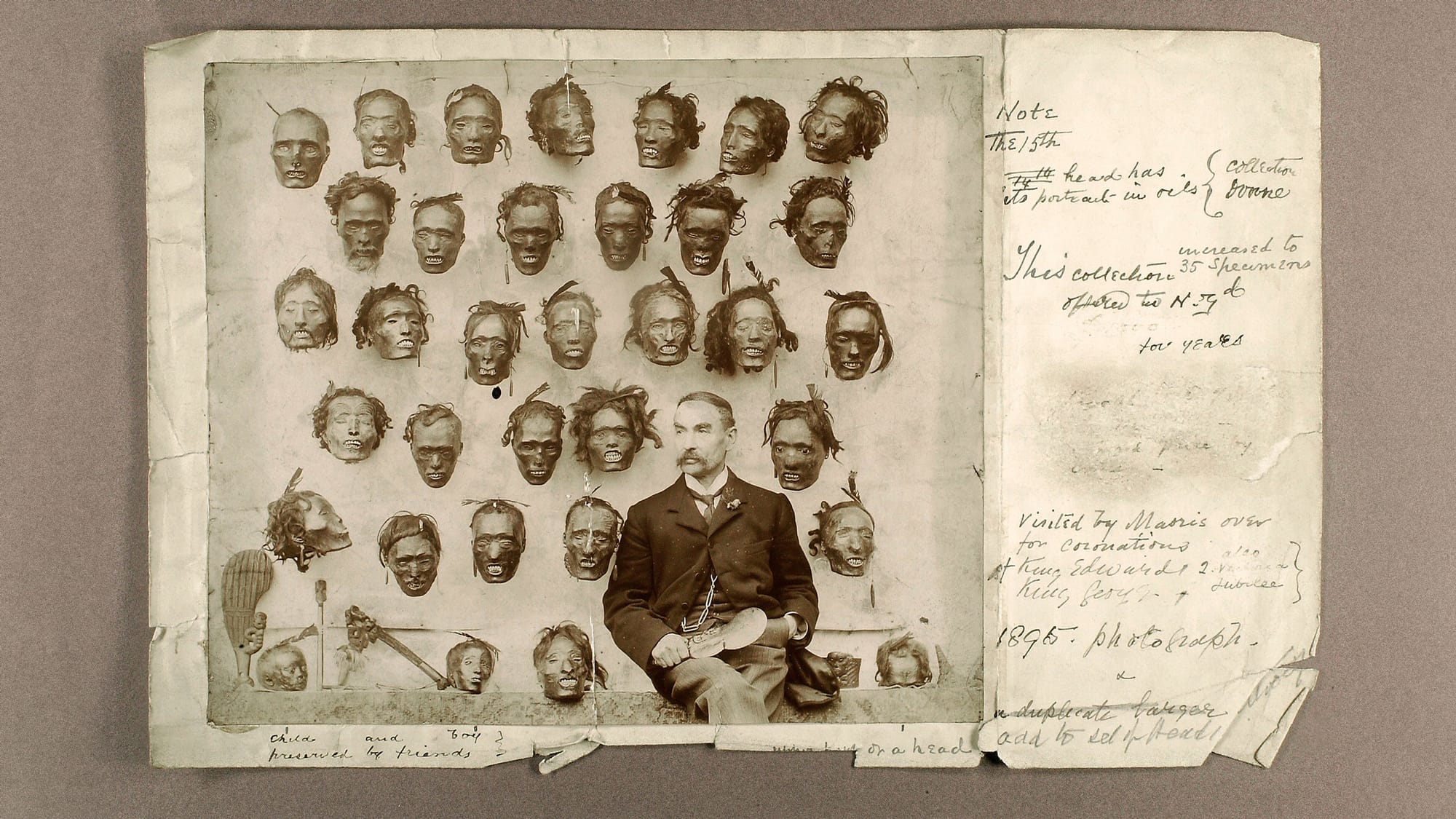

I have been collecting stories of historical body parts for as long as I can remember, or at least since I started learning about the human body, anatomy and physiology. So, most of the stories I had heard of before or I knew a little about and it was great fun being able to spend time delving further, heading down intricate rabbit warrens and learning that other people seemed just as interested as I was. For instance, the Māori Mokomokai heads were not new to me, but the backstory of them becoming Western trophies and tattooed heads being made to order was incredible to me. The current repatriation of these heads rounds that off nicely.

Unseen Histories

For all the variety, one character does recur. Can you tell us a little about the ailments of King Louis XIV of France?

Suzie Edge

When I wrote my first book Mortal Monarchs, I had to stick with the English and Scottish kings, just for editorial reasons and so many fabulous stories of kings and queens beyond British shores were missed off. When it comes to ailments, treatments and the consequences of ill health, Louis XIV had it all.

We know so much about his complaints because all his habits and his sufferings were documented. There’s a long list from gout to indigestion and insomnia to headaches. It wasn’t just his complaints that were recorded, what he left daily in his chamber pot was inspected and recorded. You can tell a lot about someone’s health from the contents of their toilet! He would undergo enemas all the time and it was likely that if you were lucky enough to have an audience with the Sun King, he was likely having an enema while you spoke.

It was fashionable to be as much like the king as possible and so when he had a successful operation on an anal abscess that turned into a fistula, others at court asked surgeons to do it to them too, whether that had a fistula or not! With the surgery being a success surgeons gained better recognition for their work. It could so easily have gone the other way had the surgeon [Charles-François Félix] failed.

Unseen Histories

A person’s physical health is central to their experience of life. But for historians it can be difficult to properly understand the medical condition of people in the past. Is this true?

Suzie Edge

It is a tricky thing to try and posthumously diagnose and the further back we go the harder it gets. Diagnosis can be hard even now with all the technology we have at our fingertips, so using historical sources is harder still. For that reason everything I do, whether it be in my books, or making TikTok videos comes with the caveat that we can only make educated guesses.

Another potential pitfall is the bias of a person’s medical specialty. I lean heavily towards surgical scenarios as that is my training, others might be more inclined to blame a symptom on endocrine or gynecological causes. I find that many of the comments I get about historical diseases or characters come from the commenter’s own experience of ill health. These can be hard to discuss with some people who can be adamant. I try to make everything I do fun and use these ‘human body history stories’ as a gateway to perhaps learning more about certain people or events. As long as we understand that nothing is certain, I think we can have fun exploring, imagining and learning.

When it comes to trophies, skulls seem to be hugely significant. When the body of a monk was dug up by a gardener on Lord Byron’s estate, rather than bury it he had it made into a drinking cup.

Unseen Histories

While the centuries come and go, is it true to say that the human body has remained relatively stable throughout recorded human history? How do our bodies today compare to those of the Greeks or Romans?

Suzie Edge

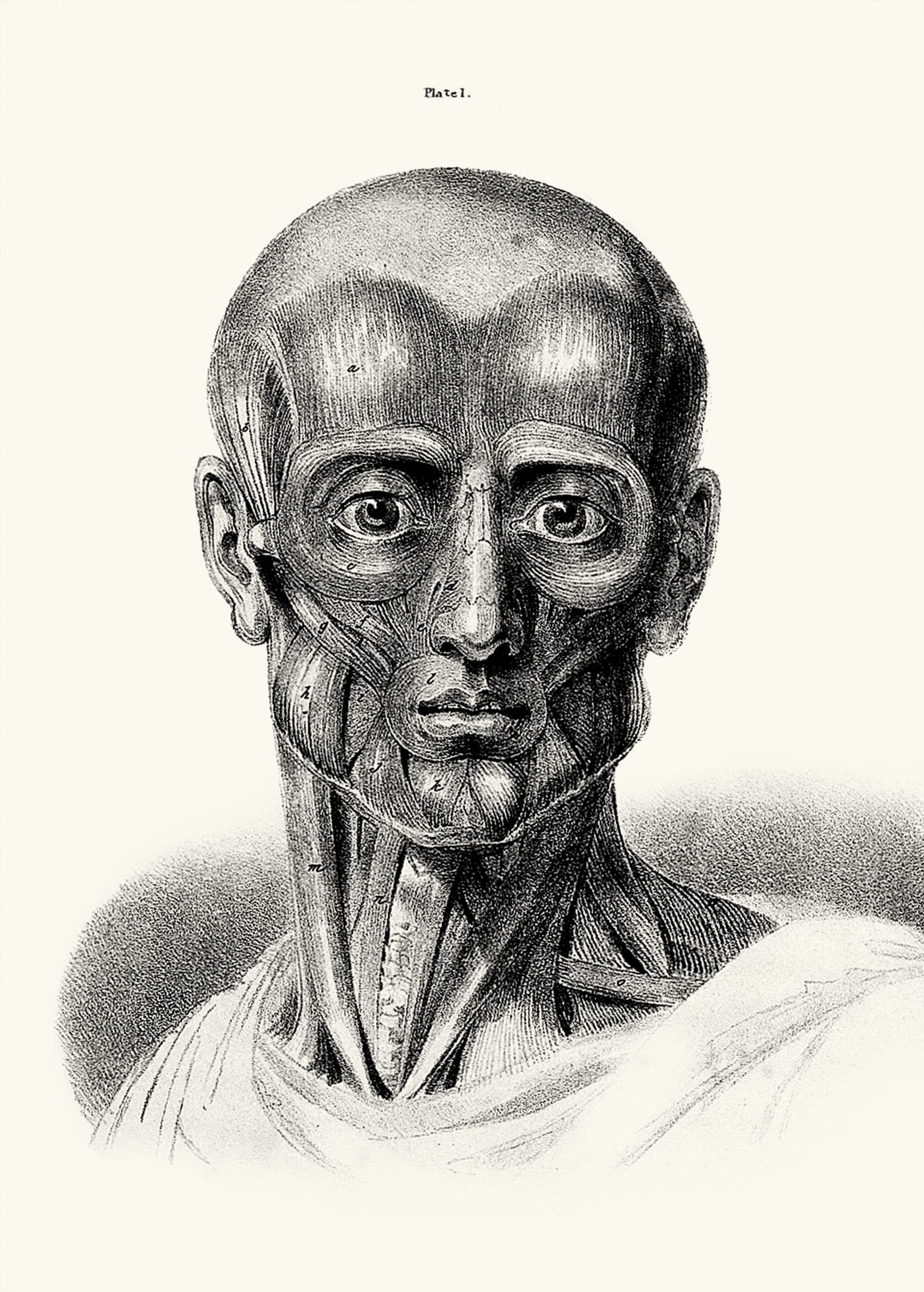

We haven’t grown or lost any organs! Over the years anatomy had remained stable. My anatomy textbooks are the only books that have not become out of date since I was at medical school! Everything else has become obsolete in those two decades but the likes of Grey’s Anatomy will remain a staple of the medical student library. Even if it has gone digital, the contents remain the same.

What’s more interesting I think is the variability through geography rather than time. I’m not just talking about the obvious differences like skin colour but also the variations in build due to access to different diets or the variability in disease patterns due to genetic variations.

Unseen Histories

Medicine aims to cure but, as we learn in Vital Organs, it has often done severe damage to patients in the past. While writing did you experience any moments of horror, when physicians were making very bad decisions?

Suzie Edge

It has always been on my mind that medics over the centuries have tried so many tactics and yet often had no positive impact at all. It’s easy to scowl at what medics have tried in the past but we are certainly not free from guilt nowadays when it comes to the likes of pharmaceuticals, and somewhat less altruistic goals such as making lots of money. Pride seems to have been a huge factor when it came to doctors getting in the way. The idea of washing away dirt was a good example of that.

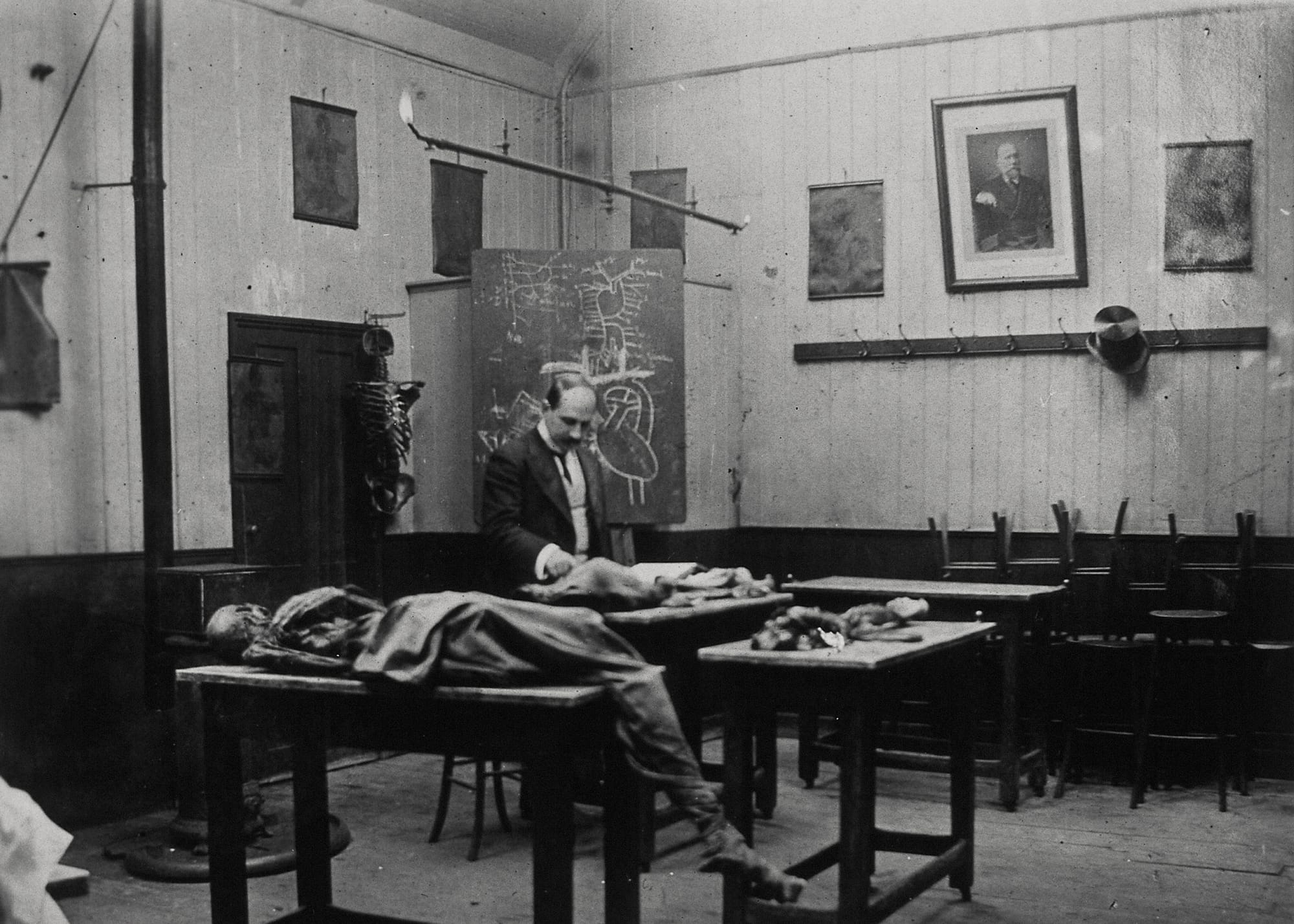

The story of Ignaz Semmelweis is being heard now thankfully. He was a nineteenth century Hungarian physician who understood that something was being carried on the hands of doctors between cadavers undergoing autopsy and mothers giving birth. Whatever was being carried about could not be seen but was causing significant morbidity and deaths by puerperal fever. He tried to encourage cleanliness, but a huge obstacle was the stubbornness of other medical men unwilling to accept they might have a hand in it, so to speak. Semmelweiss ended up beaten and dying in an asylum and yet not long later the idea of germ theory began to take hold.

Unseen Histories

People have long liked to collect body parts of significant individuals as trophies. You document quite a few instances of this in the book. Could you tell us about a few notable examples?

Suzie Edge

When it comes to trophies, skulls seem to be hugely significant. When the body of a monk was dug up by a gardener on Lord Byron’s estate, rather than bury it he had it made into a drinking cup. He wasn’t the first, many waring people over the years have drunk from the skulls of their defeated enemies, all over the world. William Shakespeare’s skull was thought to have been stolen to order from his grave and the skull of Lord Darnley, the second husband of Mary Queen of Scots turned up at auction in the nineteenth century.

Secular relics being taken from bodies long since dead and buried seemed to be a favourite past time of Georgian and Victorian antiquarians. I love that Galileo’s middle finger is sitting in a museum in Italy, positioned as you might imagine, upright in defiance at those who accused him of heresy. Body parts stolen by colonising visitors all over the world made it back to Britain, Europe and the States to be displayed in cabinets just like the heads of hunted game. It’s a sad and macabre story and one that as we said about the Maori Mokomokai, is starting to be put right.

Unseen Histories

Human organs are no longer restricted to one body. You talk about heart, liver and kidney transplants that are now increasingly commonplace. Did you find out when this aspiration to exchange body parts was first expressed?

Suzie Edge

Before writing Vital Organs I had not thought or read much about transplantation. I would tend to delve further back into history than the 1950s. I enjoyed reading about the Herricks [Richard and Ronald Herrick] and the first kidney transplant between the twin brothers.

As for the first aspirations to exchange body parts, that’s a great question and one I have not looked into. You know what I am going to be reading up on for the rest of the day now! 𖡹

Always on the lookout for gory historical details, Suzie loves telling stories of how we have treated our human bodies in life and in death. She has over 400,000 followers on TikTok who love tuning into her stories of how famous monarchs met their end.

Vital Organs: A History of the World's Most Famous Body Parts

Wildfire / Headline Publishing Group, 28 September, 2023

RRP: £18.99 | ISBN: 978-1035404582

The remarkable stories of the world's most famous body parts.

– Louis XIV's rear end inspired the British National Anthem.

– Queen Victoria's armpit led the development of antiseptics.

– Robert Jenkin's ear started a war.

All too often, historical figures feel distant and abstract; more myth and legend than real flesh and blood. These stories of bodies and its parts remind us that history's most-loved, and most-hated, were real breathing creatures who inhabited organs and limbs just like us - until they're cut off that is.

Medical historian Dr Suzie Edge investigates over 40 cases of how we've used, abused, dug up, displayed, experimented on, and worshipped body parts, including why Percy Shelley's heart refused to burn; how Yao Niang's toes started a 1000 year long ritual; why a giant's bones are making us rethink medical ethics; and the strange case of Hitler's right testicle.

"It's an incisive book (pun intended) that will leave you with a newfound appreciation of the vessel that carries you through life"

– Irish Independent

"...a bracing adventure, and one where our ancestors are not reduced to characters of myth and legend, but real people of flesh and blood. It is through this most intimate dissection that the past is brought so vividly to life."

– The Telegraph

With thanks to Isabelle Wilson