Walking the Streets of London in the 1660s

Joad R. Wren explains how he found inspiration and truth in Ralph Agas's map of London

The author of the novel All the Colours You Cannot Name, Joad R. Wren, explains how he found inspiration and truth in Ralph Agas's map of London.

Whenever I walk around London, I walk with ghosts. They will not leave me alone. It’s how we speak with the streets, the buildings, the dead; and, more importantly, how we listen to them.

When I was writing my novel, All the Colours You Cannot Name, I walked the streets of London in 1666. Walked them both metaphorically and literally. Exploring London, looking for early-modern history is fascinating, but it also helps to bring up feelings and thoughts and connections between then and now, and between the places that feature in stories.

I wanted to be faithful to the past, as faithful as I could, not least because that fidelity would enable me to locate the powerful feelings – ones that can speak to and trouble us today – in a world that felt real. The routes the characters took, the buildings they saw, how long it took them to get from one place to another, these concerned me, sometimes preoccupied me. In practical terms this meant leaning very heavily on maps.

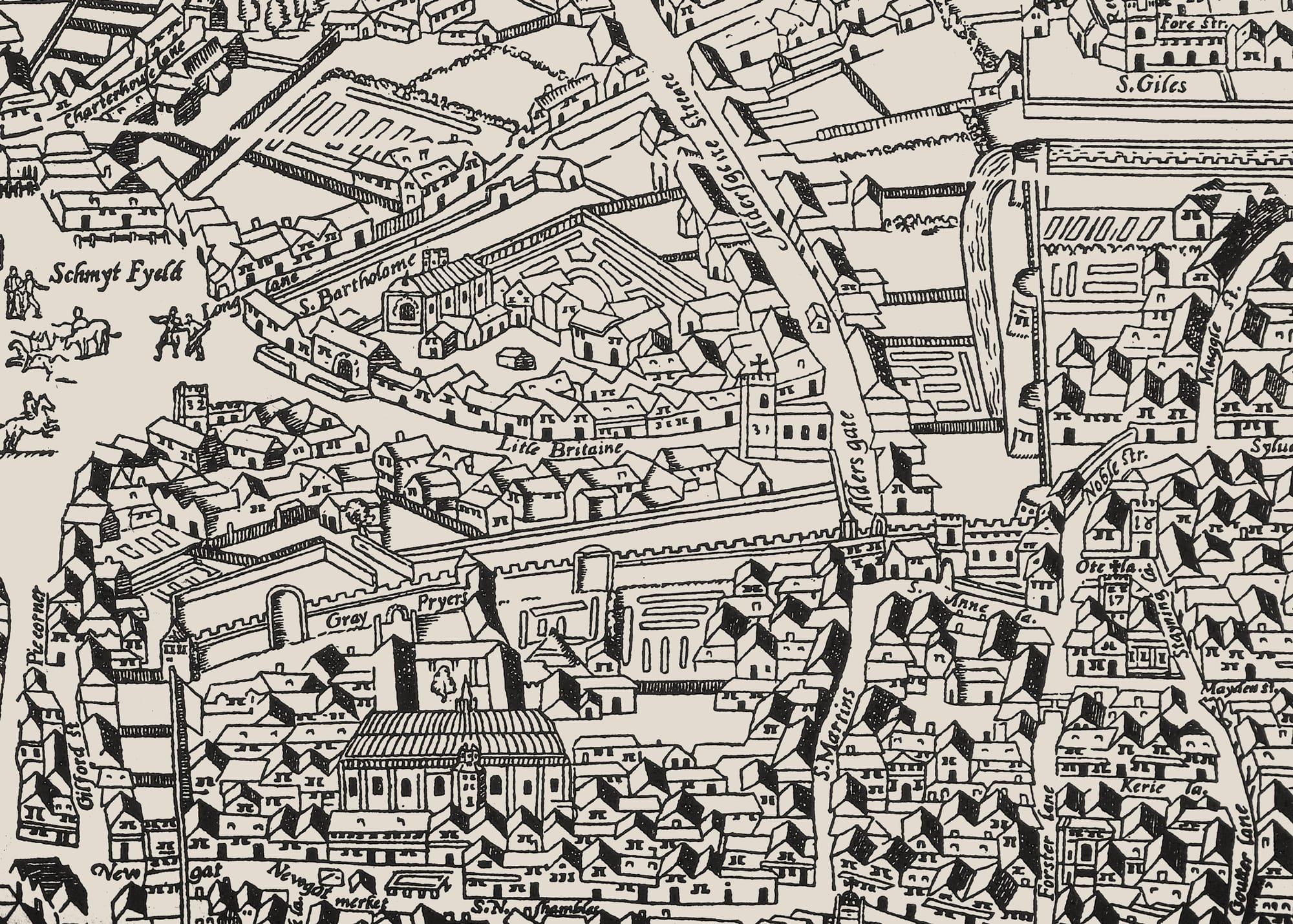

Fortunately I could access the brilliant digital edition of Ralph Agas’ map of London, first printed in 1561 and reprinted in a modified version in 1633.

You can find it here. The interface to the online edition lets you search by name and by various categories: gates, halls, prisons, churches, playhouses.

If you click on a building or a street it’s identified for you, and sometimes there’s a link to early-modern sources referring to that place. And you can zoom in to see Agas’s careful lettering of streets and alleys, his drawings of churches and houses, trees, the boats in the Thames and the people and livestock that appear in the less densely populated area.

It’s a little like the streetview function on Google Maps. It’s fascinating, compelling: you can spend hours tracing routes, getting lost.

All the Colours You Cannot Name is set in late August and early September 1666, and centres on James and Ellie White, printers who meet in 1660 and marry in 1661. They’re in their middle years, have been married before, and the story is about their coming to terms with time, loss, grief, the weight that’s already gathered when you fall in love in later life.

Obviously, the city is also dealing with the collective trauma of the Great Plague of 1665–6, which is now receding but has left anxieties and deep scars. James and Ellie live in the parish of Farringdon Without the Wall, just off Little Britain, near the church of St Bartholomew the Less. Visible from their front door – where James stands every morning, grounding himself in the place where he lives – you can see through a small gate in the city wall, just west of Aldersgate, which leads down a gravel path past Christ Church to St Paul’s.

These details emerged as I looked at a map, the story developing hand-in-hand with geography. So: the couple marry at St Bartholomew the Less, where would they gather after? The Hand and Shears Tavern (still there). And how would they walk from there to their home and printing shop? Where would they stop and kiss?

All of this is in some respects trivial. What’s the relevance of the direction they walk? Why should it matter whether Ellie could walk from Stoke Newington to their home in Farringdon after an afternoon sermon? Do the details add any real verisimilitude? Do they make the emotion more real?

There is a sense in which details do matter. In my novel there is a little republic of lonely, lost things: it’s formed of the ironwork of a printing press, the coarse weave of paper, a pot in a fireplace, whispers heard on the street, grass and mushrooms, pots and cracked cups, flags and cobbles with grass springing between them.

Truthfulness to them – and to the route you walk from Smithfield to Bread Street, the bells you hear on that walk – forms a material bedrock upon which the feelings, the love, the loss, the grief, feel more real. I hope that’s how the reader feels, anyway.

When I was writing All the Colours – in the aftermath of Covid, and suffering from the long variety without realising it – I felt I was transported by these things into the past. This doesn’t happen, or it doesn’t happen to me. when you write history. I felt I was there: I wasn’t exactly dreaming, but I could see things, buildings, bits of architecture, London bridge especially, the Thames, the skaters on the frozen river.

A map is not the territory, but it can help you enter the territory, even 350 years later. Visual elements were concrete, not exactly realistic in a CGI sort of way, but I was imagining things I wasn’t thinking about. And when I wrote the dialogue the characters were speaking, as though spontaneously. They would suggest things for me to write on their behalf.

It was exhausting. Though perhaps this was the long-term effects of Covid too: the cognitive impairment and the emotional dysregulation, and the way I repeatedly saw things in the periphery of my vision that weren’t there.

Of course maps don’t always tell the truth, or all of it. And Agas’ map is earlier than the time of All the Colours. At one point in the story I referred to St Augustine Papey – someone walked past it, or heard the bells – and only later did I notice that it had been pulled down by the time Stow wrote his Survey of London in 1598.

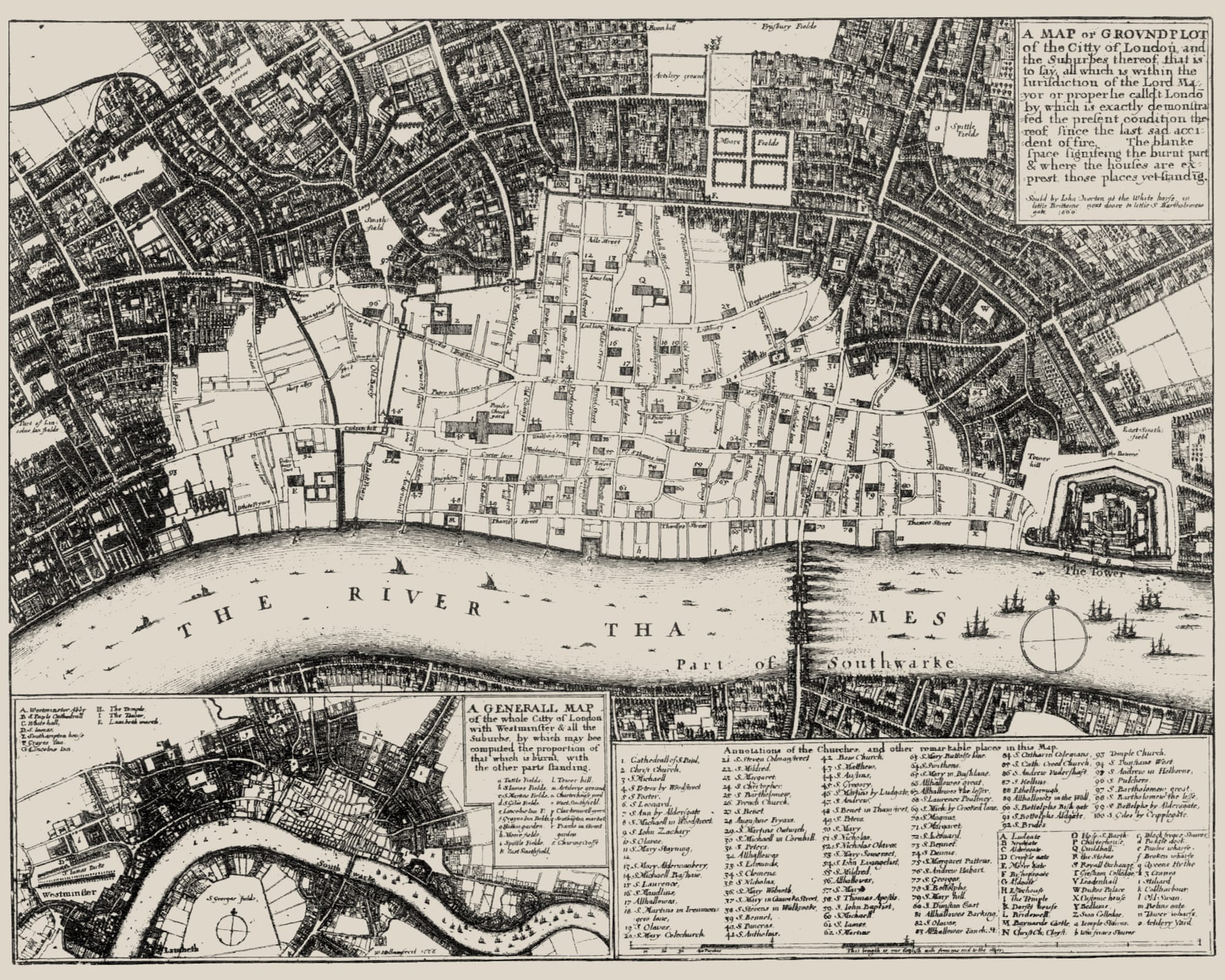

There is a 1666 map of London, engraved by the famous Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar shortly before the fire, and though it’s beautiful in its own right, it’s less detailed and less evocative than Agar’s.

Some think that anachronism is fine in historical fiction, that it can even make the characters more vivid and immediate, and I really don’t mind it in principle: but it isn’t the effect I was trying to achieve here. I’m certain that I’ve slipped, but I sought not to, and tried especially hard to avoid vicious anachronism (as opposed to harmless anachronism), mistakes that not only misrepresent but run completely against the story or the period.

I did this to the extent of checking the OED – the full, online version – for many hard words, to ensure not that my characters might have used them, but that I might have used them were I inside my own novel (it’s written in the third person). Is it credible to use the word ‘fashionable’ in a story about 1666 and not imply incorrect assumptions about society? ‘Probability’? ‘Atmosphere’? All yes.

When I walk, I walk with ghosts. This happens to James too: on one day he walks around London, consciously passing the places that tell his story. He is reliving history, processing his past, grieving, adapting. In his mind he is becoming the city, and the city is in him.

The walk excavates the story. Walking the streets has a distinctive capacity to do this, allowing us wake the histories that silently inhabit our environment. Faithfulness to geography (and historical archaeology) in fiction offers something similar: a promise to uncover the many untold stories of the streets, the long-past emotions that the buildings hold, the experiences just below the surface of the pavement.

Follow the outside of the ancient city wall, where the ditch ran, till it was blocked up and covered over with gardens: can you feel the dogs whose bodies were cast into the water, can you hear their breath? A map cannot give you this experience, but it can help you find it.

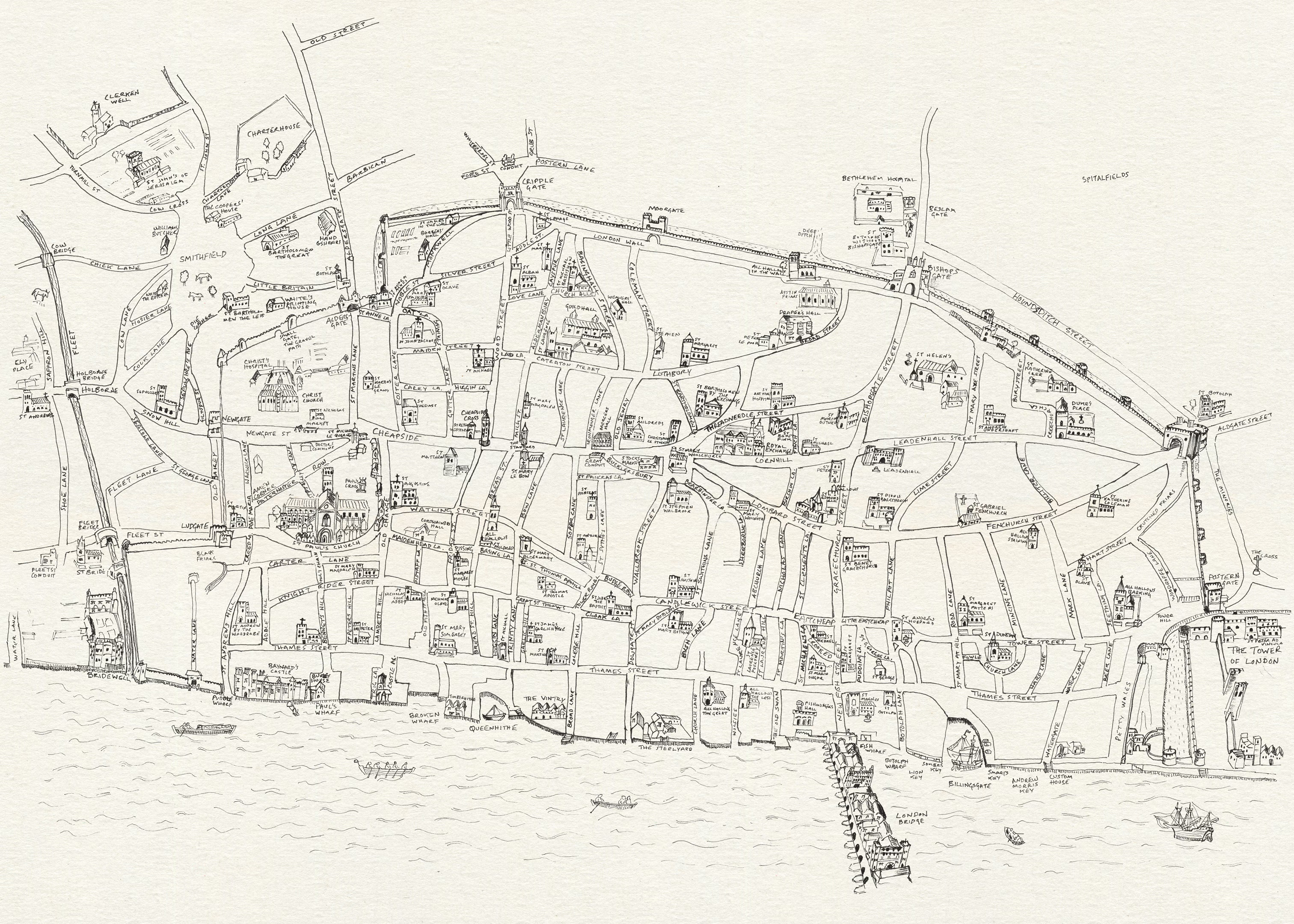

Once the novel was written it needed a map of its own, to guide the reader. I went through the manuscript and drew all of the topographical references, using the Agas map to help me place and connect them. Then I filled in the spaces in-between, streets, churches, city gates, quays and conduits.

Like Agas, this required multiple sheets, as I spilled over the edge and had to tape papers together. The fair copy appears at the start of All the Colours You Cannot Name. Once the map was complete, my wife Georgina (who did the painting on the cover) and I took it, and walked the semi-concealed footprint of the city walls, recorded in ruins and names and plaques. It almost worked, and we found our way to the Hand and Shears and St Bartholomew the Less, paying a pilgrimage to an imagined history that became more real with every step •

This feature was originally published March 22, 2024.

All the Colours You Cannot Name by Joad R. Wren

Poetry Wales Press, 25 March, 2024

RRP: £9.99 | 272 pages | ISBN: 978-1781727201

“A rare book that moves so quietly, that delves so deeply into what it feels to love and to face loss. A memorable, slow triumph” – The Times

It is 1666 and the bubonic plague still haunts London. Just outside the old Roman walls, where they have lived for six good years, printers James and Ellie White have managed to escape its ravages.

The city too has survived, but now sits in a cloud of wounds. After over a year, something like everyday life has been restored, and the preacher Solomon Eagle wants a book printed, in which he moralises on the meanings of the plague and the judgements of God.

James and Ellie accept his commission and set to work but James is plagued by a breathless trepidation. Then everything changes when the unexpected happens. Caught in the dream-like place between the past and their future, with former lives to unlive and a grief they can hardly speak, they must hold onto each other, and their love, in order to survive. Lyrical and visceral in equal measure, All the Colours you Cannot Name is a compelling and deeply tender story of love and death.

“A hauntingly vivid story of the Great Plague of 1666, written with spare grace and intelligence, along with a compelling historical realism. A very fine and very moving fiction”

― Financial Times

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store