Welcome to the Migrants' Supper Club

A visit to her ancestral home in Samarkand inspired Or Rosenboim to establish a dining club on her return to London

In 2018, shortly after her return from Uzbekistan, the academic and writer Or Rosenboim decided to set up an experimental dining club, inspired by the cultural heritage of her family.

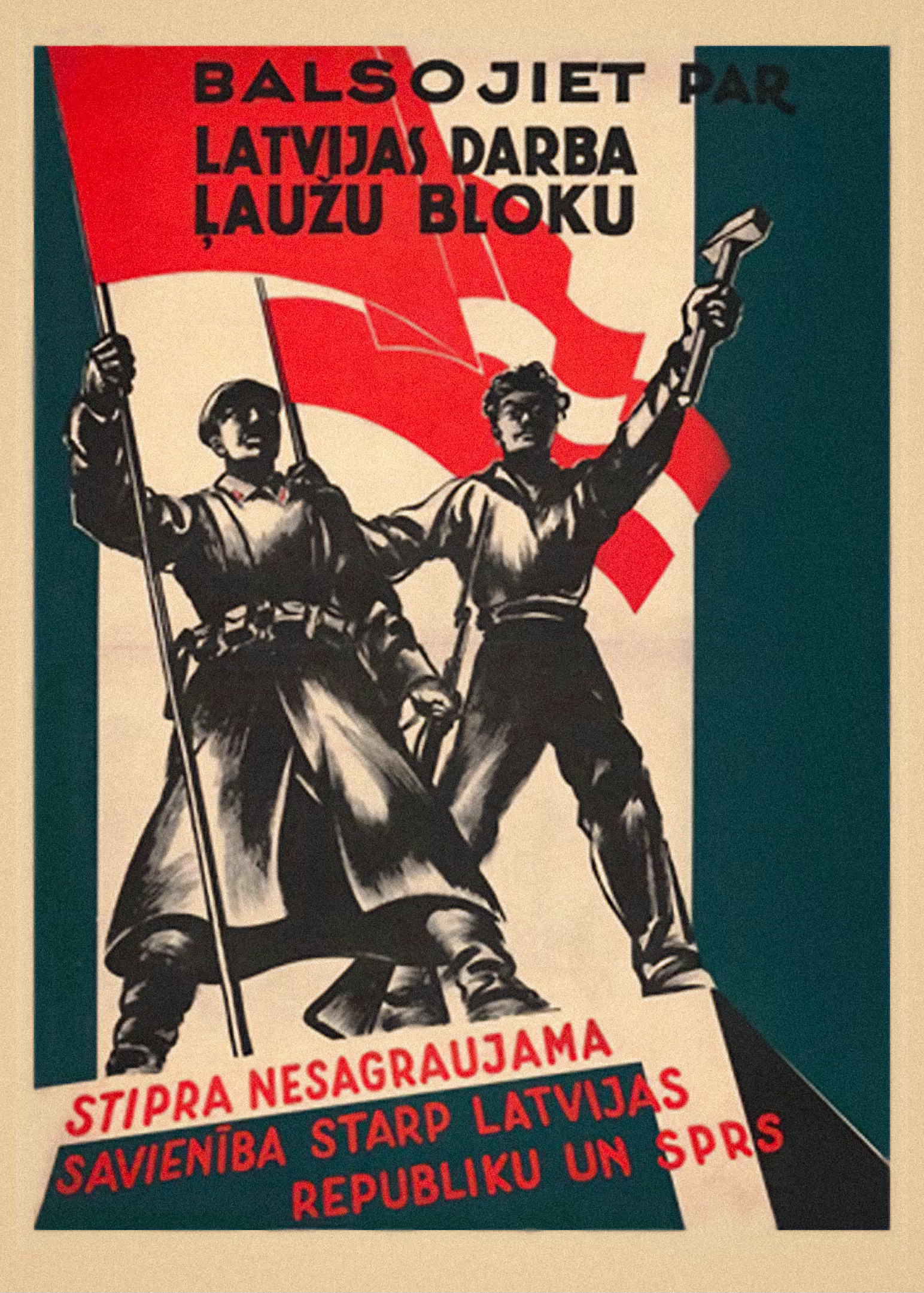

'The Migrants' Supper Club' was based in London and grounded in the humanistic ethos of connection. Each of its gatherings was themed around a twentieth century migration route. From Jerusalem to Moscow, Riga to Tajikistan, the locations linked Rosenboim with the lives of her ancestors.

In this article, Rosenboim explains more about the beginnings of the Migrants' Supper Club, and how her initiative evolved during the subsequent years of pandemic and conflict.

I arrived in Samarkand in June 2018. It was a hot dusty day, and when I disembarked the train from Tashkent, the city was coloured in a shade of yellow. I left my bag in my small family hotel in the old city, and stepped into a local restaurant to escape the sand storm.

Almost a century earlier, the Asheroff family, my ancestors, had left this city, never to return. My great-great grandfather Zion Asheroff was a trans-imperial merchant who lived between Samarkand, Moscow, Istanbul and Jerusalem. After the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, he refused to live under a communist regime and decided to move permanently to the Middle East.

It had been my life-long dream to visit the city that lived so vividly in my family’s stories and food. But when I was sitting there, at the Samarkandi restaurant, savouring a delicious plate of manti meat dumplings, I realised that the story of my family could not be confined to any one city; it was a story about life on the road.

The experiences of displacement, within the Russian and Ottoman Empires, defined my ancestors’ identity more than their place of origin or their journey’s destination. If I really wanted to understand their past, I would have to reconstruct their travels.

When I returned to London, a few weeks later, I decided to set up the Migrants’ Supper Club, an experimental initiative aimed at sharing the histories and food of migrants.

I wanted to give my guests a flavour of the food of the road, the changing recipes of people on the move. I launched a series of themed dinners, each replicating a migration route of the twentieth century, inspired by my own family’s past.

Every month, a group of guests gathered at my London home for a special meal. There was a dinner following merchant families from Samarkand to Jerusalem at the turn of the 20th century, another that traced the stories of Second World War refugees from Riga to Tajikistan, and a feast celebrating the food of Eastern Mediterranean merchant-travellers.

Not all migration routes had to be international: one of the meals was inspired by the small-scale history of displacement of my partner’s family, from Genoa to Turin in Italy.

Around the table, I found an immense pleasure in sharing my family’s food with new people, often migrants themselves, who were keen to discover also the stories behind the recipes, tales of migration and displacement that many know little about.

The events soon became a word-of-mouth success, and then Covid-19 hit. During the long lockdown evenings, I longed for the thrill and joy of the Migrants’ Supper Club parties. I started to write down the stories of displacement that I shared with my guests.

The recipes were the starting point of my exploration, but it was not easy to find historical documents to recount the history of my ancestors. They were ‘ordinary people’, rarely mentioned in official records or in state archives. I wanted to tell the story of the women of the family, wives and mothers, cooks, merchants and refugees, who travelled across continents with their families in tow.

But women were almost completely absent from the archival files. The historical investigation was further complicated by the history of the places where they had lived, cities and territories that changed hands between emirates, empires, and later nation-states.

Eventually, I got lucky. A distant cousin sent me the memoir of my great-great grandfather, Zion Asheroff, and my grandmother shared the memoir of her father, Zion’s son.

The Adirims, another branch of my family, were based in the Baltics until they fled their home and found refuge in Tajikistan during the Second World War. The Latvian archives provided insight on their movements from the early 20th century until they left Riga in 1941.

It wasn’t a lot to start with, but along with oral history interviews, photos, and recipes, I had enough to trace the routes of displacement of the three strands of my family.

I wrote about the Asheroff family from Samarkand, who travelled via Odessa and Moscow to Jerusalem from the mid-19th century to the 1920s. I followed their steps to the great bazaars of Istanbul and Kokand where they would sell precious fabrics from Central Asia and delicious Mediterranean cheese.

The family’s favourite recipes merged together the flavours of these regions, cooking delicious rice palao with olive oil, and adding lemon and chickpeas to the sauce of their stuffed vine leaves. Their food was not exactly the traditional dishes of any of these places, but a unique combination of them all.

I wrote about the Adirim family, who from the Baltic region travelled across Russia to Central Asia in the 1940s. They were not merchants, but refugees who fled their home in Riga just before the German occupation. The Adirim women spent the war years in Tajikistan, where they found not only shelter and nourishment, but also new flavours very different from the Nordic cuisine they were used to in Riga.

I researched the Mizrahi family, whose commercial networks spread all around the Ottoman Empire. Although their past was shrouded in mystery, I knew that they had lived in Palestine for generations. They saw themselves as Mediterranean ‘Levantines’, and cooked simple, delicious food that could be found in the market restaurants of Jerusalem, Alexandria and Aleppo.

But slowly, as nationalist tensions mounted, they started feeling out of place. Their regional, eastern sense of belonging was marginalized in a world of nation-states.

The memory of these families, and their women, is what this book is about. My family lived through the decline of Asian and European empires, the Soviet Revolution, and two global wars. At different times in their lives they were travellers or home-dwellers, wealthy or destitute, merchants or refugees.

As I reflect on their lives, I feel that they tell us a broader story about how our sense of belonging is more complicated than we realize. None of these people could know, when they set off for the road, what their final destination would be or when would their journey end. Whatever the path, food was their companion on the road.

Events beyond what any of these people could foresee eventually led them to make their home in Palestine. The Asheroffs and Mizrahis settled there between the 1880s and the 1920s. The Adirims joined them after 1949. When war broke in 1948 between the Jewish and the Arab communities in Palestine, one of my grandparents fought with the newly formed Israeli army.

That war displaced whole Palestinian communities, including those expulsed from the city of Jaffa where my grandfather opened his shop. The story of the displacement of these Palestinian families has tragically not ended yet.

As I write these words, war and hunger are once more devastating these lands. A sense of solidarity among those who, at one point or another, have lost their home, is now needed more than ever. I hope that this book can inspire humanity and compassion, as a promise of a more peaceful future •

This feature was originally published May 22, 2024.

Her award-winning book The Emergence of Globalism: Visions of World Order in Britain and the United States, 1939–1950 was published by Princeton University Press in 2017 (paperback, 2019). She has written for various international magazines and websites, and co-authored with Ilana Efrati an art and food book, Orto: Nature, Inspiration, Food (2019). She has lived in Tel Aviv, Bologna, Paris, Los Angeles, Cambridge and Florence.

Air and Love: A Story of Food, Family and Belonging

Picador, 15 May, 2025

RRP: £10.99 | ISBN: 978-1529098129

“This is a moving memoir about how recipes are formed by migration, love and loss, even within a single family” – Bee Wilson, author of The Secret of Cooking

As a child, Or Rosenboim’s knowledge of her family history was based on the food her grandmothers cooked for her – round kneidlach balls in hot chicken broth, cinnamon-scented noodle kugel, stuffed vine leaves, herby green rice with a squeeze of fresh lemon juice and aubergine in tomato sauce.

She knew that her family had a complex past but it was only reading her grandmothers’ recipe books after they both died that she began to explore that past for the first time.

The result is a vivid chronicle of displacement and escape, retracing the complex network of journeys her family took from Samarkand and Riga to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in search of safety and a better life, punctuated by the food they ate and cooked along the way.

Today, though, these journeys, and this long tradition of migration, would now be almost impossible. A beguiling mixture of history, memoir, travel and food, Air and Love is also a fresh and deeply human retelling of some of the major stories of the twentieth century.

“A fascinating book. ‘’Food of the road’: through memory, history, recipes — and love — a family, and an era’s, complex story is movingly traced”

― Judith Flanders, author of Rites of Passage

With thanks to Kieran Sangha.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store