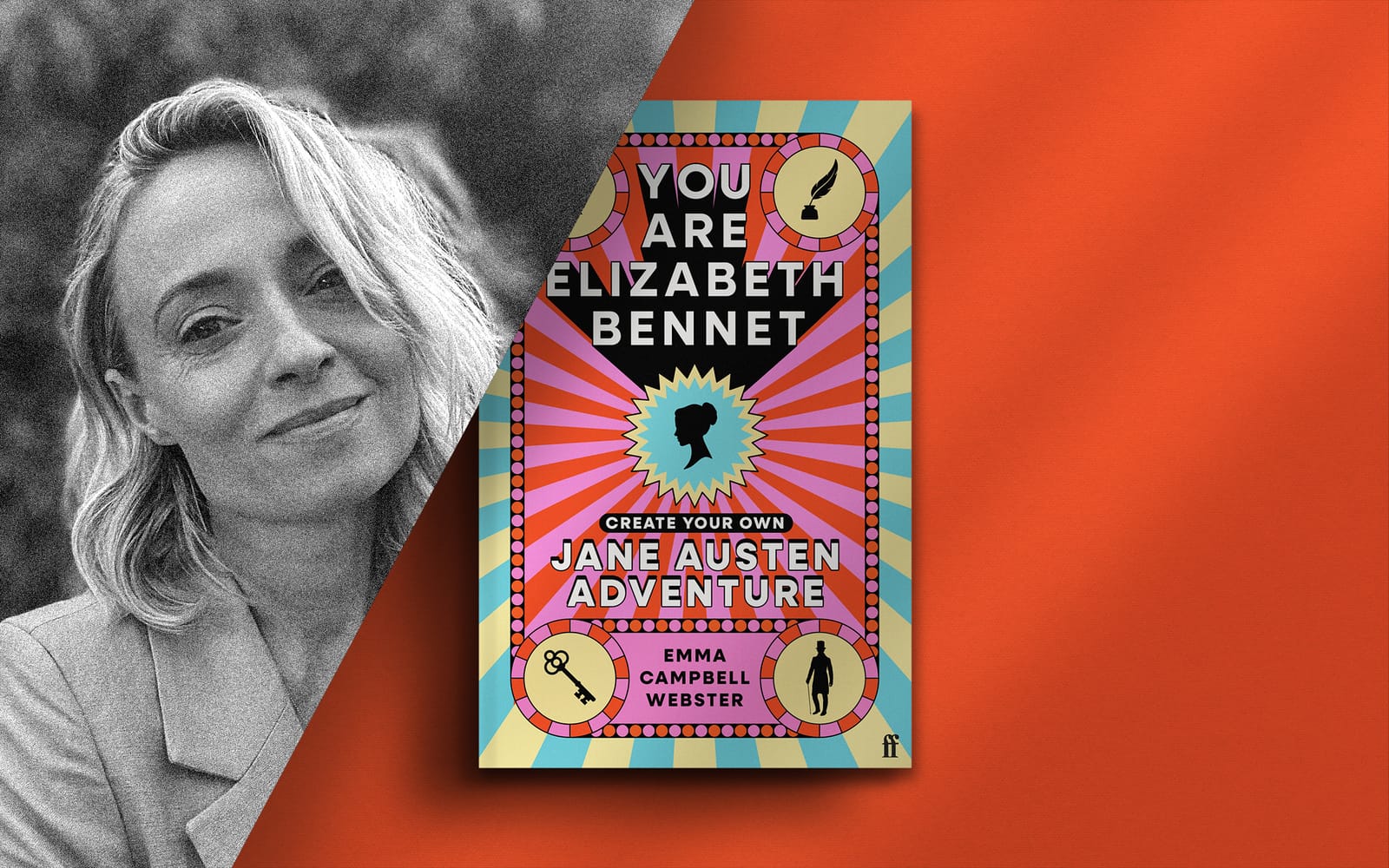

What Matters in Jane Austen?

250 years after she was born, Jane Austen continues to outwit her readers, as John Mullan explains

There are few greater pleasures for readers than a Jane Austen novel.

Funny, beautifully observed and daringly written, her books also survive today as a window into a vibrant moment in British history.

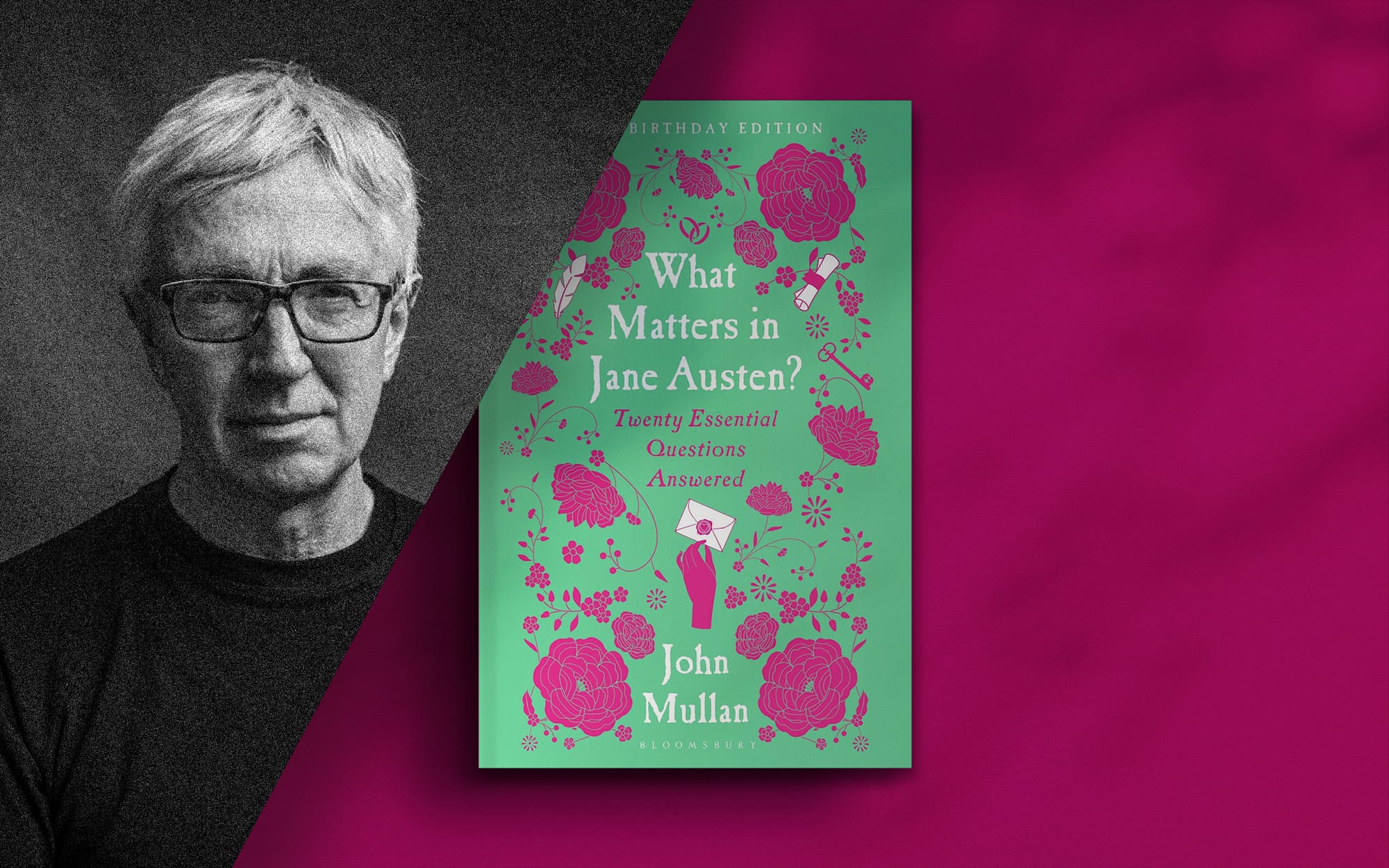

In this interview John Mullan, the author of What Matters in Jane Austen, explains what it is that makes her so very special.

Questions by Peter Moore

Unseen Histories

There is a tendency to think of Jane Austen as a rather safe, sentimental writer who produced domestic novels about romance. Do you think it is difficult for people to appreciate how daring she was in her time?

John Mullan

Yes – her audacity is widely underrated – or simply missed. Her materials might have seemed limited ('three or four families in a country village,' as she put it) but her methods were innovative.

By refracting her narration through the minds of her characters, she revolutionised the English novel. The reader now has to work out why people are behaving as they do. And to call her ‘sentimental’ is the opposite of the truth: she is utterly unsentimental (which is why some readers even think her cruel).

However, her novels are comedies, which means that (like Shakespeare’s comedies) they all end in marriage. This does not mean she had sentimental ideas about marriage – just look at her pictures of unhappy or unsatisfying marriages in all her novels.

Unseen Histories

Your study, What Matters In Jane Austen, is grounded in a close reading of her novels. Can you tell us about your first encounter with her?

John Mullan

I first encountered her as a teenager at school: I studied Persuasion for A-level, and had an excellent teacher who got us to read Emma as well.

I could see that she wrote beautifully, cleverly, wittily, but I fear that I thought they were rather inconsequential. Then I read Tony Tanner’s Penguin Classics introductions to some of the novels, which made them seem deep and unsettling. Then, eventually, I came to teach Austen, and the students made me see how the novels endlessly repaid minute attention.

Unseen Histories

How would you characterise Austen prose in comparison with others of her time? Patrick O’Brian, for instance, called her that ‘Great Mistress of the Semi-Colon’. Do you enjoy any particular aspect of her style?

John Mullan

I would quarrel with Patrick O’Brian: her real signature punctuation mark is the dash, most often used when she is dramatising the thought processes of one of her heroines. She uses it like no novelist before her.

How about this passage from Emma, as Emma sits at her dressing table late at night after Mr. Elton has proposed to her in the back of her carriage (when she assumed he would propose to her foolish protégé, Harriet Smith):

“The hair was curled, and the maid sent away, and Emma sat down to think and be miserable.—It was a wretched business indeed!—Such an overthrow of every thing she had been wishing for!—Such a development of every thing most unwelcome!—Such a blow for Harriet!—that was the worst of all. Every part of it brought pain and humiliation, of some sort or other; but, compared with the evil to Harriet, all was light; and she would gladly have submitted to feel yet more mistaken—more in error—more disgraced by mis-judgment, than she actually was, could the effects of her blunders have been confined to herself.”

Pretty nifty exclamation marks, too! As Emma’s thoughts flash through the narrative, you can see her beginning to convince herself that she is acting unselfishly.

Austen’s prose changes between her novels. The prose style of her first published novel, Sense and Sensibility, still owes a good deal to eighteenth-century models, notably Samuel Johnson: plenty of ‘periodic’ sentences, with pairs of balanced phrases and clauses (and plenty of semi-colons). She soon puts this behind her.

Unseen Histories

The Regency Age is one suspended between the loose Georgians and the starchy Victorians. Can you see the influence of both in Austen’s novels?

John Mullan

The Regency Age, with its permissiveness, for the upper classes only, and its love of easy fashion is there in Austen’s novels but brought to life rather than indulged.

Think of Mary and Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park: they are attractive exemplars of a new culture – liberated, cultured, pleasure-loving, unstuffy – but they are also amoral monsters, in an alluring and civilised shape.

There is nothing starchy about Austen’s novels, but they certainly don’t have a good word for hedonistic aristocrats. There are plenty of men (and a few women) behaving badly. Austen’s realism is that the men mostly get away with it.

Victorian novels tend to want to reward or punish their characters. Lydia Bennet would come to a very grisly end in Victorian fiction. In Pride and Prejudice, it is unbowed. ‘Lydia was Lydia still; untamed, unabashed, wild, noisy, and fearless’. It’s poetry, really. And look! There is one of Patrick O’Brian’s much-loved semi-colons.

Unseen Histories

One of your chapters concerns the age of her characters. For women, in particular, age was of critical importance. Can you give an example of a point where this is a decisive factor in the novels?

John Mullan

In Austen’s earliest novel, Northanger Abbey, the heroine, Catherine Morland, is just 17, and the whole novel follows the giddiness of teenage experience.

Everything happens in a hurry (including her courtship) and with the odd mix of insight and foolishness appropriate to Catherine’s youth – and disarming youthfulness.

In Austen’s last novel, Persuasion, the heroine, Anne Elliot, is 27, and has supposedly lost her ‘bloom’. At 19, when she was supposedly at her marriageable peak, she turned down the man she loved, Frederick Wentworth, and has spent eight years regretting it. No wonder she is no longer blooming! But he returns and is slowly won back to her, and suddenly 27 is not so old at all.

All the characters in the novels are super-age-conscious, but they are often wrong-headed as a result. Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility (aged 17) says that 'A woman of seven and twenty can never hope to feel or inspire affection again' – but she is ridiculous.

Unseen Histories

It is considered rather cliché today for authors to discuss the appearance of a character’s eyes. But in Pride and Prejudice you explain how Elizabeth Bennet’s become a plot point in themselves. Can you tell us a little about this?

John Mullan

Austen is very sparing of physical description – she gives us the material to imagine how people look, without specifying. But we do get details about Elizabeth’s dark eyes. Remember Mr. Darcy after his first encounter with Elizabeth: ‘no sooner had he made it clear to himself and his friends that she had hardly a good feature in her face, than he began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes’.

He (and we) notice her eyes because he is always looking at her – and, we infer, she at him. They are caught in a mutual attraction that they don’t like to acknowledge, and the novel catches us up in this too.

Unseen Histories

In the early nineteenth century the idea of the ‘seaside resort’ was growing in fashion. Lydia Bennet, for instance, is transfixed by the idea of a visit to Brighton. You point out that such places were infused with danger in the contemporary mind. Why?

John Mullan

At the seaside (but I think that this is still the case) social conventions and even dress codes were loosened. You were there for pleasure, and could encounter and talk to people that you hardly knew. You were there to see and be seen, but with a kind of frivolity and gaiety – we might say, holiday spirit – that were unlike the fashionable inland resorts of Bath or Cheltenham.

Because conventions were less constraining, there might be danger in the air. Even more so, because it was becoming usual for young couples to have their honeymoons at the seaside. So, seaside resorts had a kind of sexiness that Lydia surely found alluring.

Unseen Histories

Much of the tension in Austen novels depends on details which are archaic today: entailed estates, ages of majority and annual allowances. Did you have to read many history books yourself to fully grasp the meaning and emotional depth of her novels?

John Mullan

No! You absolutely don’t have to read history books in order to ‘get’ the details of Austen’s novels. Austen had a rather miraculous ability to supply knowledge of the conventions on which she was relying.

The entailed estate in Pride and Prejudice is implicitly explained (not least by Mr. Bennet to Mrs. Bennet) in the course of the opening chapters. It is as if she knew that readers in future ages would need some help with these.

In Sense and Sensibility, we need to know that couples can contract secret engagements, but the man who has his proposal of marriage accepted cannot, in honour, change his mind – while the woman can. This is made clear as the plot develops.

The first volume of Pride and Prejudice is structured around three dances or balls. At the first of these, the Meryton assembly ball, Mr Darcy declines to be introduced to any young lady, so he can only dance with Charles Bingley’s sisters, whom he already knows.

At the last of these, the Netherfield ball, Elizabeth must dance with Mr. Collins first, because he has asked her, and if she declines him she must decline all others. Such period protocol will be understood by any attentive reader, without reading any other books. It is as if Austen knew that we would be reading the novels two centuries later and would need things to be made clear.

Unseen Histories

Austen is a very funny writer. Her depiction of Mr Collins must be regarded as one of the great comic creations in English literature. Do you have any favourite characters or moments?

John Mullan

I adore Mrs. Elton in Emma. In life, I would hide in order to avoid her, but on the page, I cheer whenever she appears. She is the very acme of vulgarity and self-admiration, always talking about herself with fake self-deprecation.

“I have the greatest dislike to the idea of being over-trimmed—quite a horror of finery. I must put on a few ornaments now, because it is expected of me. A bride, you know, must appear like a bride, but my natural taste is all for simplicity; a simple style of dress is so infinitely preferable to finery. But I am quite in the minority, I believe; few people seem to value simplicity of dress,—show and finery are every thing. I have some notion of putting such a trimming as this to my white and silver poplin. Do you think it will look well?”

Emma cannot stand her, and sees through her pretence of considerateness. But, as well as being Emma’s rival as queen bee of Highbury, she is also her distorted mirror image, even using some of the same turns of phrase.

Every single thing she says (and she loves to talk) is inadvertently hilarious. Her relationship with her recently acquired husband, Mr. Elton, is horrible and delicious.

Unseen Histories

What Matters in Jane Austen was originally published some years ago. What new have scholars of her work/life taught us about her since then?

John Mullan

I am going to side-step this question, because I think that Jane Austen teaches the scholars more than the scholars will ever teach her readers.

The best Austen scholars simply try to do justice to her ingenuity and subtlety, there in every sentence, every line of dialogue. Academics who try to press their own ‘new’ readings on her novels invariably come to grief. She is cleverer than any of us •

This interview was originally published September 30, 2025.

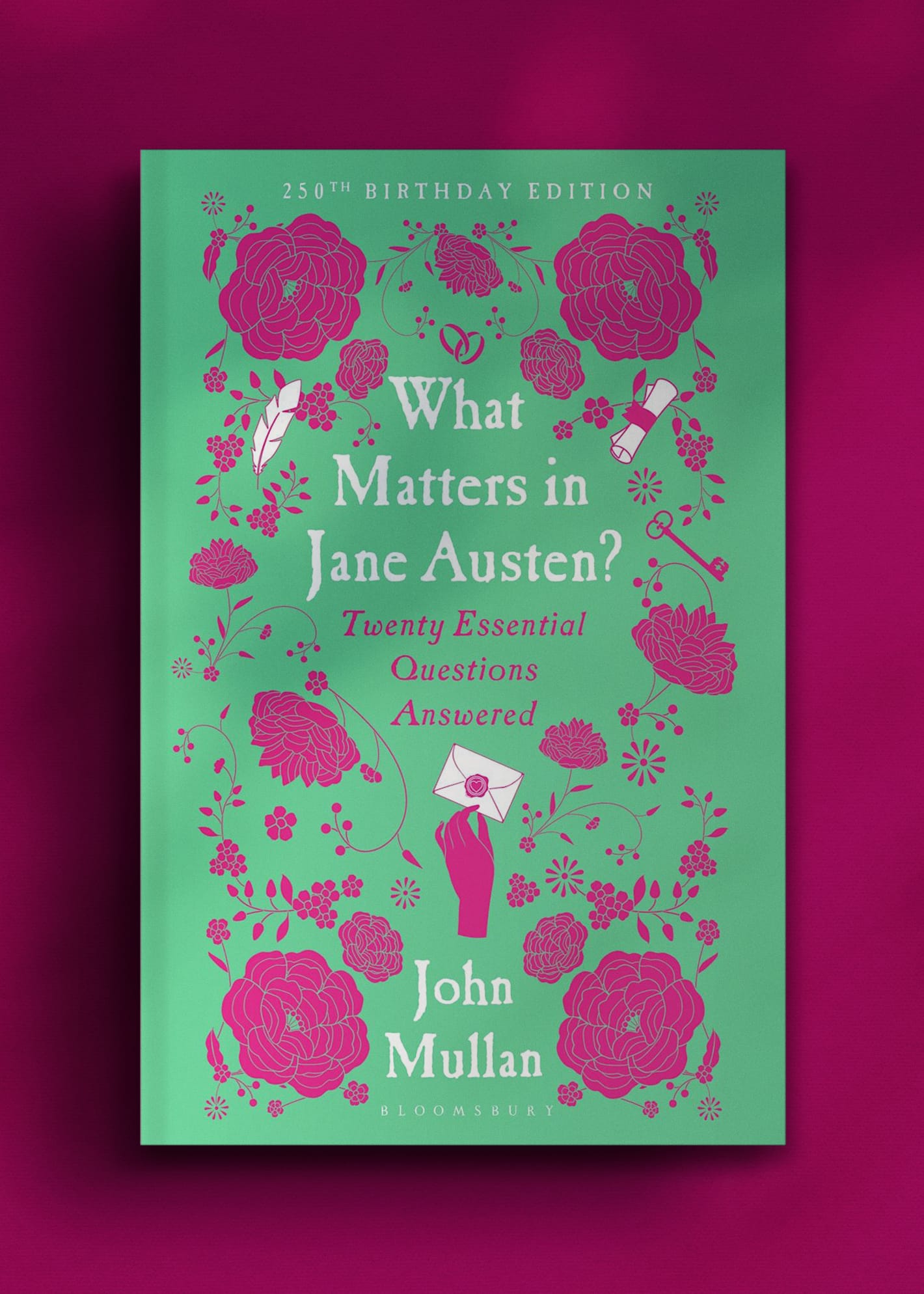

What Matters in Jane Austen?: Twenty Essential Questions Answered

Bloomsbury, 22 May 2025

RRP: £10.99 | ISBN: 978-1526693945

“Almost as good as finding an unpublished novel” – The Lady

Is there any sex in Jane Austen? Why do her plots rely on blunders? Which important characters never actually speak?

In twenty short chapters, each of which answers a question prompted by Jane Austen's novels, John Mullan illuminates the themes that matter most to the workings of Austen's fiction. Inspired by an enthusiastic reader's curiosity, based on a lifetime's study and written with flair and insight, What Matters in Jane Austen? uncovers the hidden truth about an extraordinary fictional world.

“Any new book on Jane Austen raises the urgent question, Would I get more pleasure from reading this than from re-reading my favourite Jane Austen novel? If you decide to give What Matters in Jane Austen? a chance you'll know after a few pages that you've made the right choice”

– Sunday Times

With thanks to Helena Yurdakul. Author Photograph © Paul Musso

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store