Why Are We Drawn to Mountains?

George Mallory, one of the central figures in the history of mountaineering, was haunted by this simple question, as the author Daniel Light explains in this excerpt from The White Ladder.

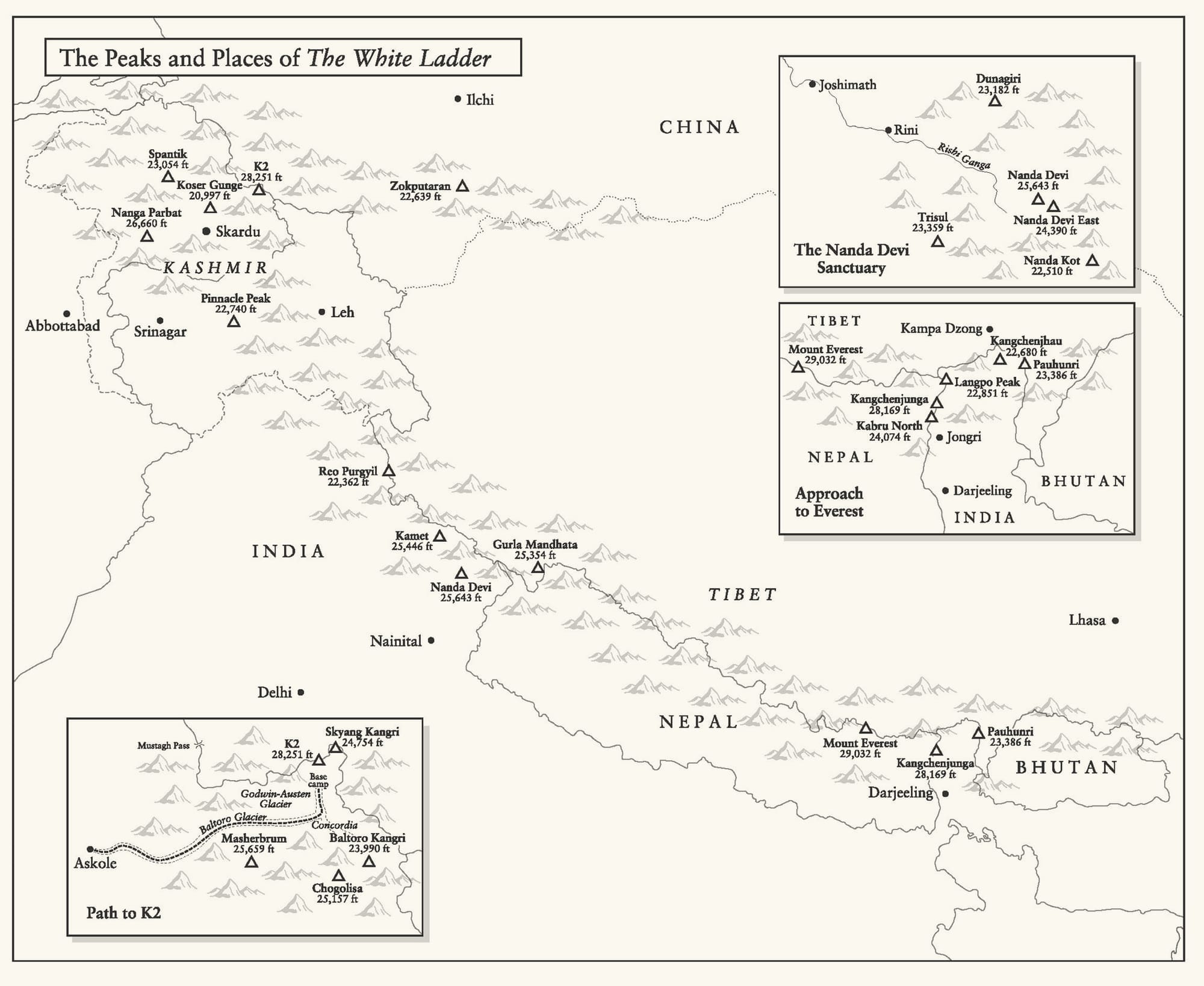

In 1909 the American geographer Fanny Bullock Workman memorably described her attempts to scale a challenging mountain face. 'We trod silently', she wrote, 'the white ladder of approach to the mysterious unknown'.

This phrase, 'the white ladder', has, a century on, provided the writer Daniel Light with a title for his sweeping new history of mountaineering.

Workman's line also captures something of the powerful allure that many climbers have experienced but few have managed to explain. Just what was it that draws so many upwards into 'the mysterious unknown'?

One who was repeatedly asked this question was the pioneering Himalayan climber George Mallory.

In this prologue taken from The White Ladder, Light frames Mallory's answer to this most testing of questions.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Daniel Light

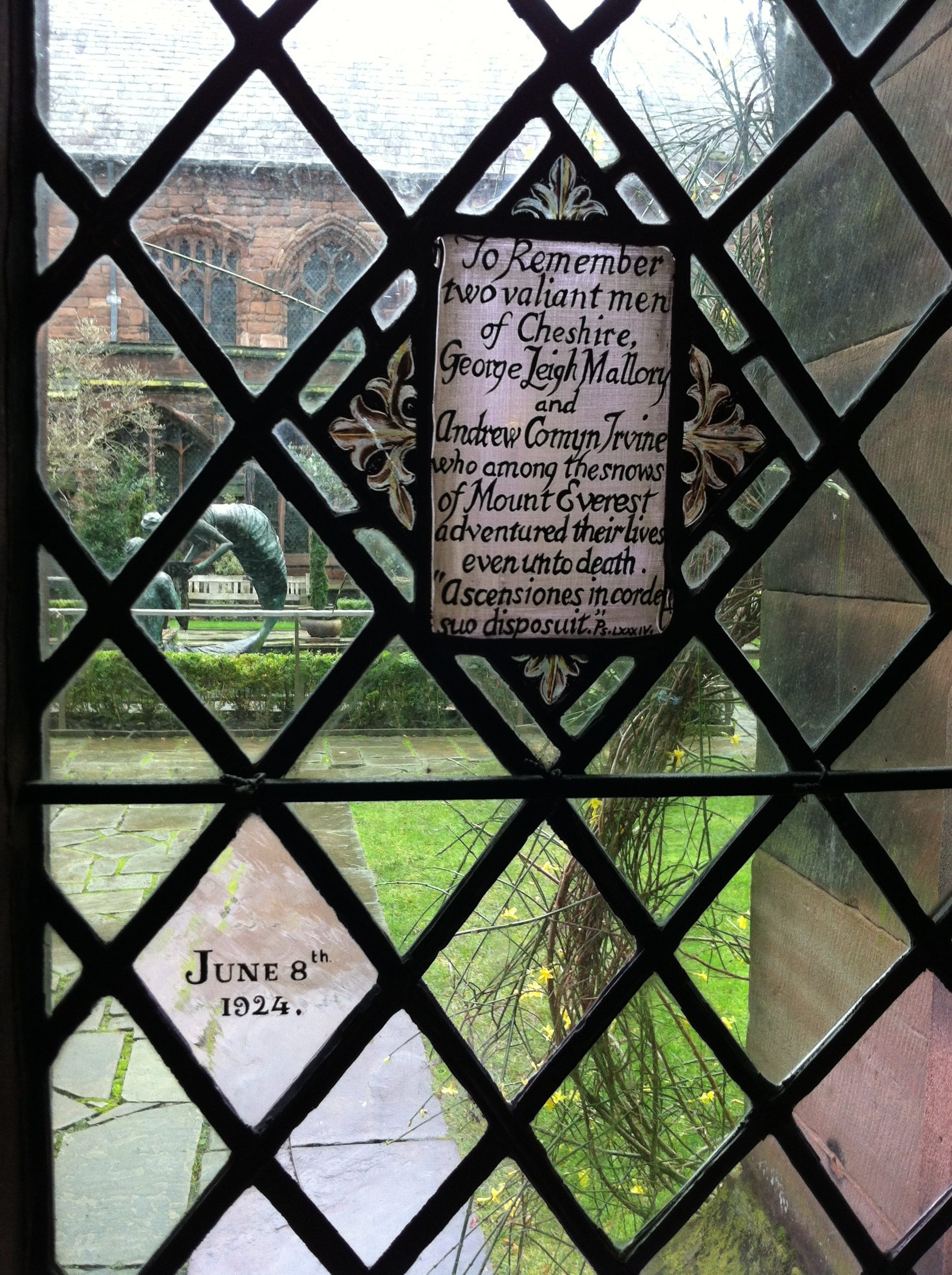

George Mallory was the only person to participate in all three of the British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s. He and Sandy Irvine would be lost on the mountain in 1924, leaving their camp high on the northeast ridge and disappearing into light cloud on a still June day.

The discovery of Mallory's body in 1999 did little to dispel the mystery and romance surrounding his life - and death - as the most gifted climber of his generation. Today many still speculate as to how high he and Irvine went on that last bid for Everest's summit and, more to the point, why they were there at all.

— Daniel Light

'Because it is There'

Mallory was bored.

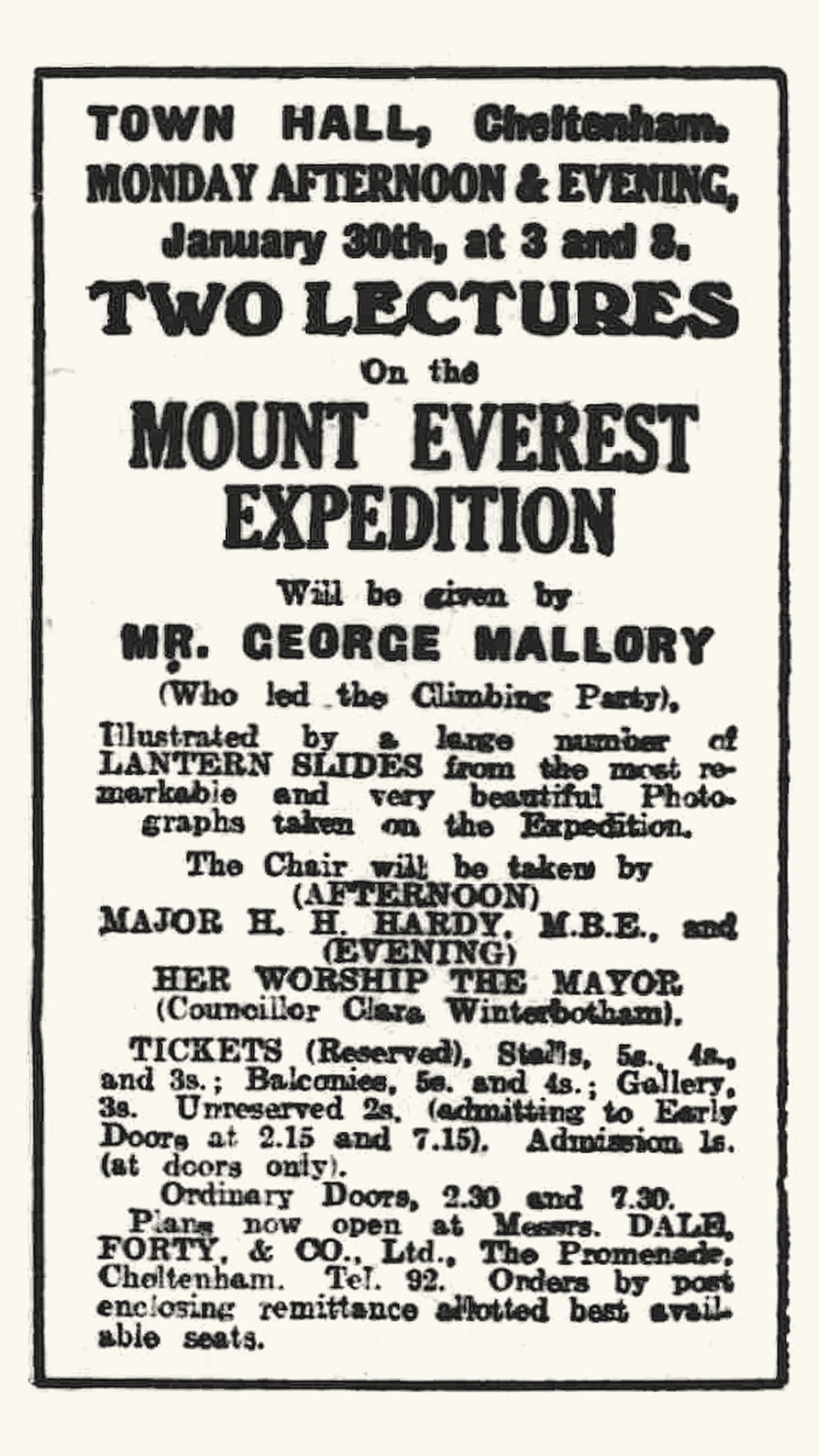

Bored of giving the same old talk, with the same old photographs, on the same old lecture tour. Disheartened by the mixed reception on the other side of the Atlantic, by half-full venues and lacklustre reviews. And, when the lights came up, always the same question.

Why?

Might as well ask a dog why it howls at the moon. Mallory was a climber. At seven, he’d been scampering up drainpipes on his father’s church; at twelve, it was the chapel of Winchester College. Mount Everest was a higher calling, of course, but at heart he was still that boy from Birkenhead, climbing ‘like he did not expect to fall’.

Why?

Some question for a soldier, a veteran of the Great War. Mallory had served in the Royal Artillery, had made a target of himself scaling trees and church towers, spotting for his battery. He had gone to the trenches on reconnaissance missions, had seen bodies sinking into Picardy clay. Those who had seen so much death knew life was for living. Those who had been to such depths knew mountains were for climbing.

Why?

He had a family to think about. He and Ruth had married six days before Britain entered the war; the children barely knew him. Why disappear into the mountains when everything that mattered most was back home? Except Mallory didn’t know how to be a husband or a father, any more than he knew how to be a soldier or a teacher. The only thing that came naturally to him was to climb.

[Left] Like the polar explorer Ernest Shackleton and others of his age, George Mallory took to the lecture circuit to raise funds and interest in the geographical work that he was doing. Occasionally he was exasperated by the questions he faced (Public Domain) Newspaper 'Advert.Gloucestershire Echo. 25 January 1922.' Unseen Histories Library [Right] Memorial to George Leigh Mallory and Andrew Comyn Irvine in Chester Cathedral (⇲ Public Domain) Photograph Andrew Abbott

But why? Why put yourself in such danger?

Because it was dangerous. Seven men had died on the last Everest expedition, Sherpas killed in an avalanche. For many, they were just porters, indigenous intermediaries pressed into the service of the British. Mallory knew them as skilled guides and mountaineers, men with their own understanding of what it meant to walk in Everest’s shadow. They had names – Dorje, Lhakpa, Norbu, Pasang, Pema, Sange and Temba. They had families.

Mallory blamed himself. He had led them into trouble. They shouldn’t have been on the mountain so late in the summer.

Then a weather window opened, tempting good mountaineers into bad decisions. So much experience among the British. Everest made novices of them all.

Now there was talk of having another go. Why? Because they almost had it. George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce had gone to within two thousand feet of the summit, until Everest was the only mountain they could see ‘without turning our gaze downwards’.

Exhausted, with time against them, a malfunction with their oxygen equipment turned them back.

But for one stroke of bad luck, they might have climbed the world’s highest mountain. How could they give up now?

‘So,’ said the reporter, a young lady from the New York Times. ‘Why exactly is it that you want to climb?’

Mallory sighed.

Go ask the past.

Go ask the pioneers.

Go ask the mercenaries and spies, risking their lives, wearing disguises so good they fooled themselves. Ask soldiers and surveyors, labouring through the lowlands, forcing frozen passes, in the stamping ground of somebody else’s gods. Ask the alpinists and cragsmen, showmen and Because it is There 3 charlatans, peasants and princes, writing their names into record books and sometimes into stone. Ask the amateurs and professionals… ask them all, who first clapped eyes, set hearts, fixed hands on the highest mountains in the world. Go ask the past, demand your truth from visionaries and seers.

Then listen, as their answers echo back across the years ■

Dear Odell, — We’re awfully sorry to have left things in such a mess—our Unna Cooker rolled down the slope at the last moment. Be sure of getting back to Camp IV to-morrow in time to evacuate before dark as I hope to. In the tent I must have left a compass—for the Lord’s sake rescue it; we are without. To here on 90 atmospheres (pressure in the oxygen cylinders) for the two days—so we’ll probably go on two cylinders. But it’s a —— load for climbing. Perfect weather for the job! —

Yours ever, G. Mallory

(The last known words written by George Mallory before his death on Mount Everest, June 1924)

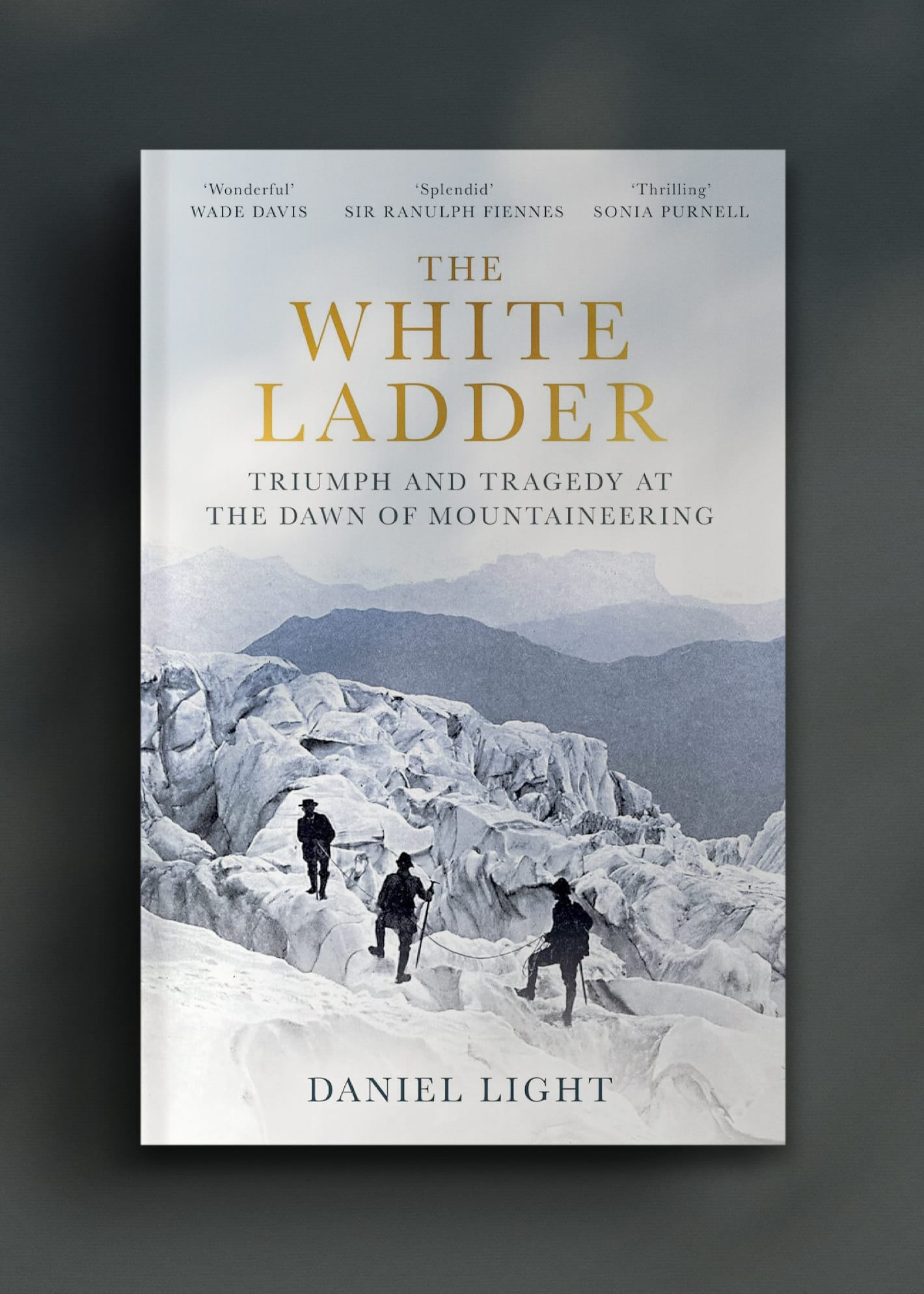

Excerpted from the prologue to Daniel Light's The White Ladder: Triumph and Tragedy at the Dawn of Mountaineering.

The White Ladder: Triumph and Tragedy at the Dawn of Mountaineering

Oneworld, 5 September, 2024

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0861548163

The true story of the thrill-seekers, map-makers, soldiers, occultists, artists and porters who paved the way for modern mountaineering.

There are the devout Incan priests who, scaling the Andes’ icy slopes to pay tribute to each mountain’s ‘Great Lord’, travelled higher than any European would for centuries. The Gurkha riflemen who joined their commanders in canvassing the Karakoram, admiring the distant summits of Broad Peak and K2 with gleeful anticipation. The tweed-clad mountaineers who made the first serious assaults on Everest, hauling yards upon yards of battered rope through the cold.

Tracing the world altitude record from the ashy slopes of the sacred volcano Llullaillaco to the icy crags and crevasses of the Karakoram, Daniel Light takes a panoramic journey through the storied history of mountaineering before Everest. Joining a cast of colourful characters, The White Ladder offers an ode to mountains’ capacity to enthral, and the fundamental human drive to climb higher and higher.

"Thrilling... Daniel Light delivers stories that are poetic, spiritual and astonishing in their courage and drive" – Sonia Purnell, author of A Woman of No Importance

"Wonderful… a massive story with an enormous cast of characters, among them some of the most compelling figures of mountaineering history" – Wade Davis, author of Into the Silence

With thanks to Kate Appleton