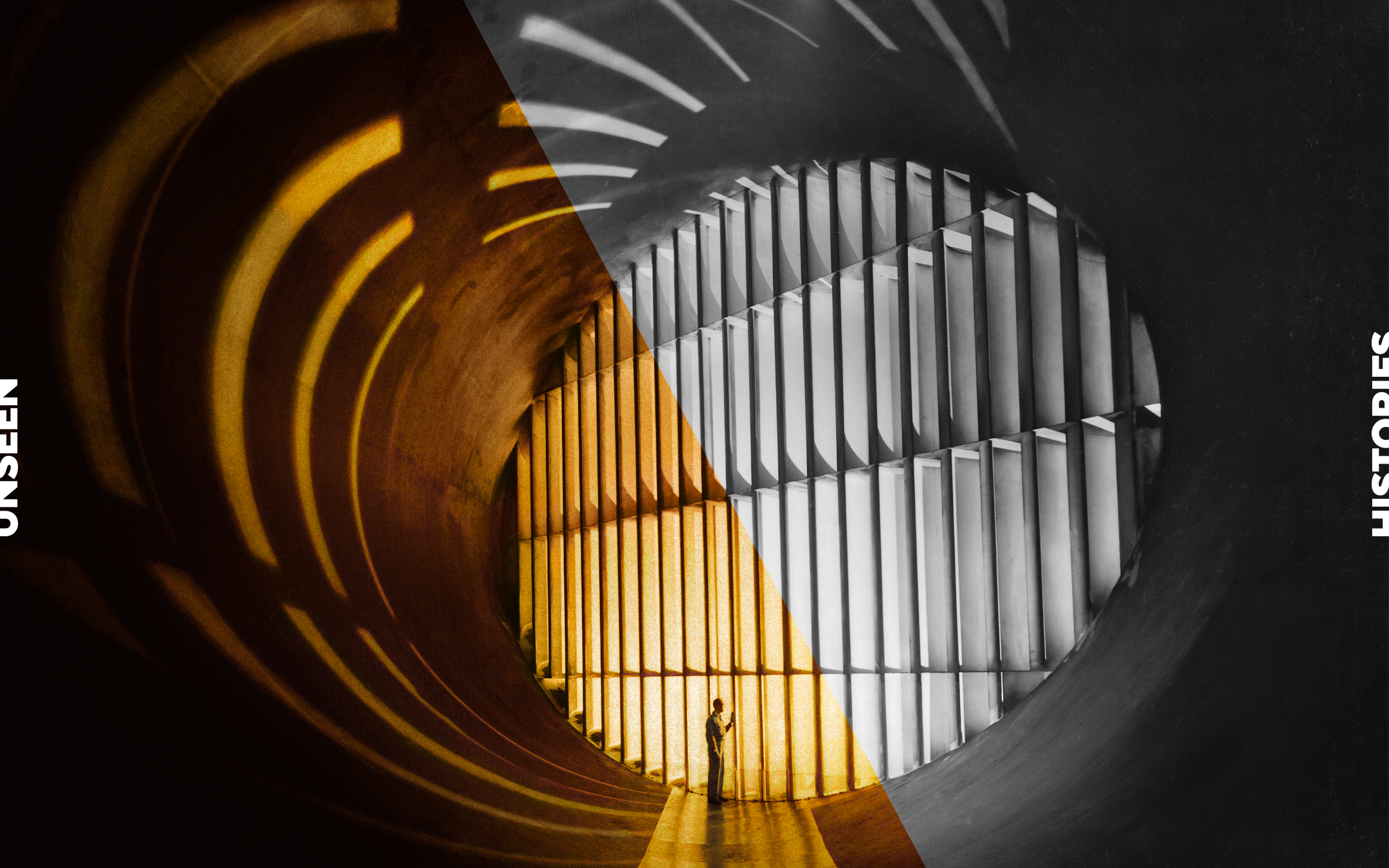

Wind Tunnel at Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, 1950

This poignant image shows both the power and frailty of humanity

Snapshot is an ongoing series revealing the story behind a single picture from the archives.

"So smooth are the insides of the tunnels that even a postage-stamp stuck on the wall can completely upset the even balance and uniform flow of air streaming past at up to 3,000 miles an hour."

On 15 March 1950, this striking photograph was taken at Langley Aeronautical Laboratory in Virginia. It is a poignant image that suggests both the power and frailty of humanity. The slight figure of the man, standing at the end of the wind tunnel, is dwarfed by the technology and arcs of light that surround him.

And yet, for all this disproportion, the overall sensation is one of control and power. The 1950s was a decade when a mastery of practical science was changing the nature of life on Earth. The figure at the centre of this composition was part of a generation whose ultimate achievement came in July 1969 when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon.

This photograph, however, belongs to an earlier moment in that story. Technology was evolving fast in the years that directly followed World War Two. Disbelieving reports in the newspapers told of plastic domes that were afloat in the Atlantic, housing equipment for the US Radar. Others spoke of strange, self-assembly fibre-glass huts that were completely weatherproof. From Massachusetts came news of a hypersonic research facility, while at Crystal Palace in London, people stared in awe at the BBC's huge new transmitting station.

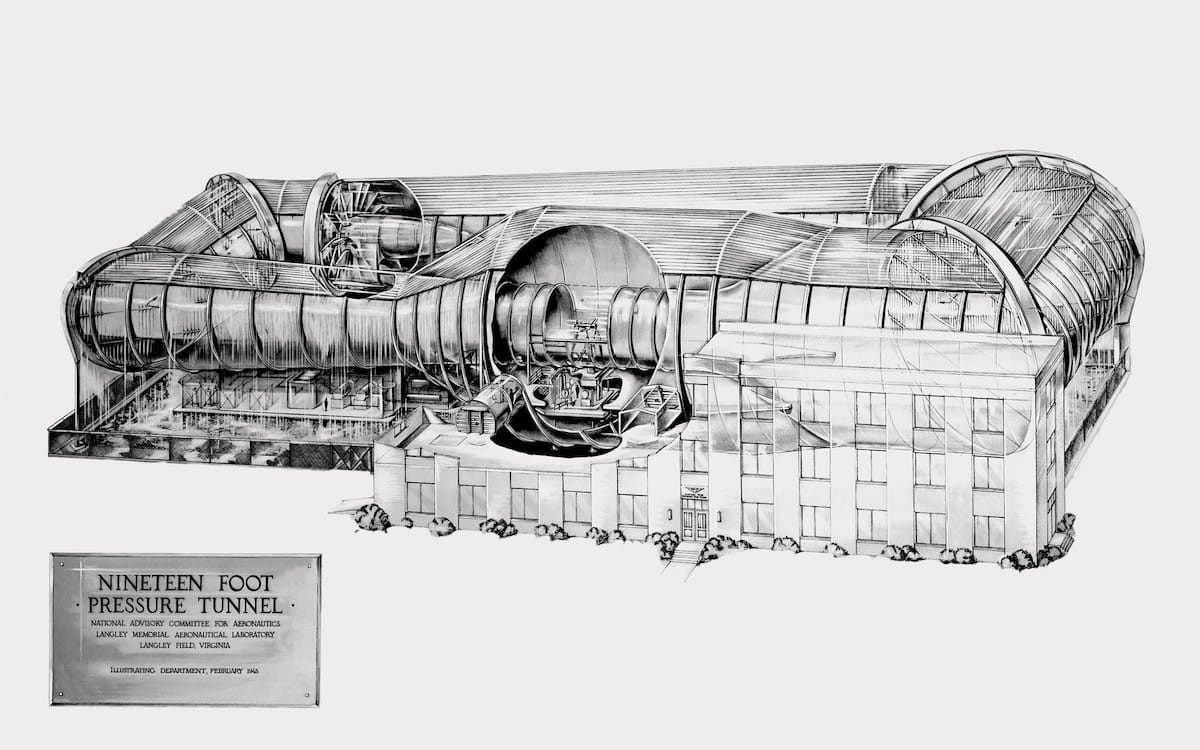

This view (below) of the 19-foot pressure wind tunnel at the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory belongs to the same historical moment. Throughout the early and mid-twentieth wind tunnels like this had been constructed. They were used for the testing and development of aeroplanes and, as time wore on, space technology.

The wind tunnels enabled technicians to replicate the conditions of flying at anything between 300-3,000 mph. According to a feature article printed in the Illustrated London News in 1955:

1955

In the early years of the last war, wind tunnels were relatively simple in design and construction, built at a cost of a few thousand pounds. Those of to-day are major engineering projects, costing millions of pounds. Britain’s largest wind tunnel, now being built by the Ministry of Supply at the National Aeronautical Establishment near Bedford, occupies a 20-acre site and has cost about £5,000,000.

There, aerodynamic research into hypersonic speeds—perhaps in the region of 15,000 miles an hour—will ultimately be carried out. Some of its test gear is claimed to be equal or superior to anything of its kind in the world. So smooth are the insides of the tunnels that even a postage-stamp stuck on the wall can completely upset the even balance and uniform flow of air streaming past at up to 3,000 miles an hour. Many of the details of this and similar projects are still highly secret.

While the British were proud of the progress they were making at the National Aeronautical Establishment, they still lagged far behind the Americans. In 1952, just a few years after the featured photograph was taken, John Slack, the 44-year-old assistant director and his associates at Langley had been presented with the Collier Trophy. This was America’s most prestigious aviation award, and it was given for their pioneering work on their wind tunnels.

The citation stated that their new tunnel ‘appears to have given America a head start of at least two years over any potential enemy in the design of transonic aircraft’. At a time when the Cold War was growing ever cooler, this was significant indeed. 𖨠