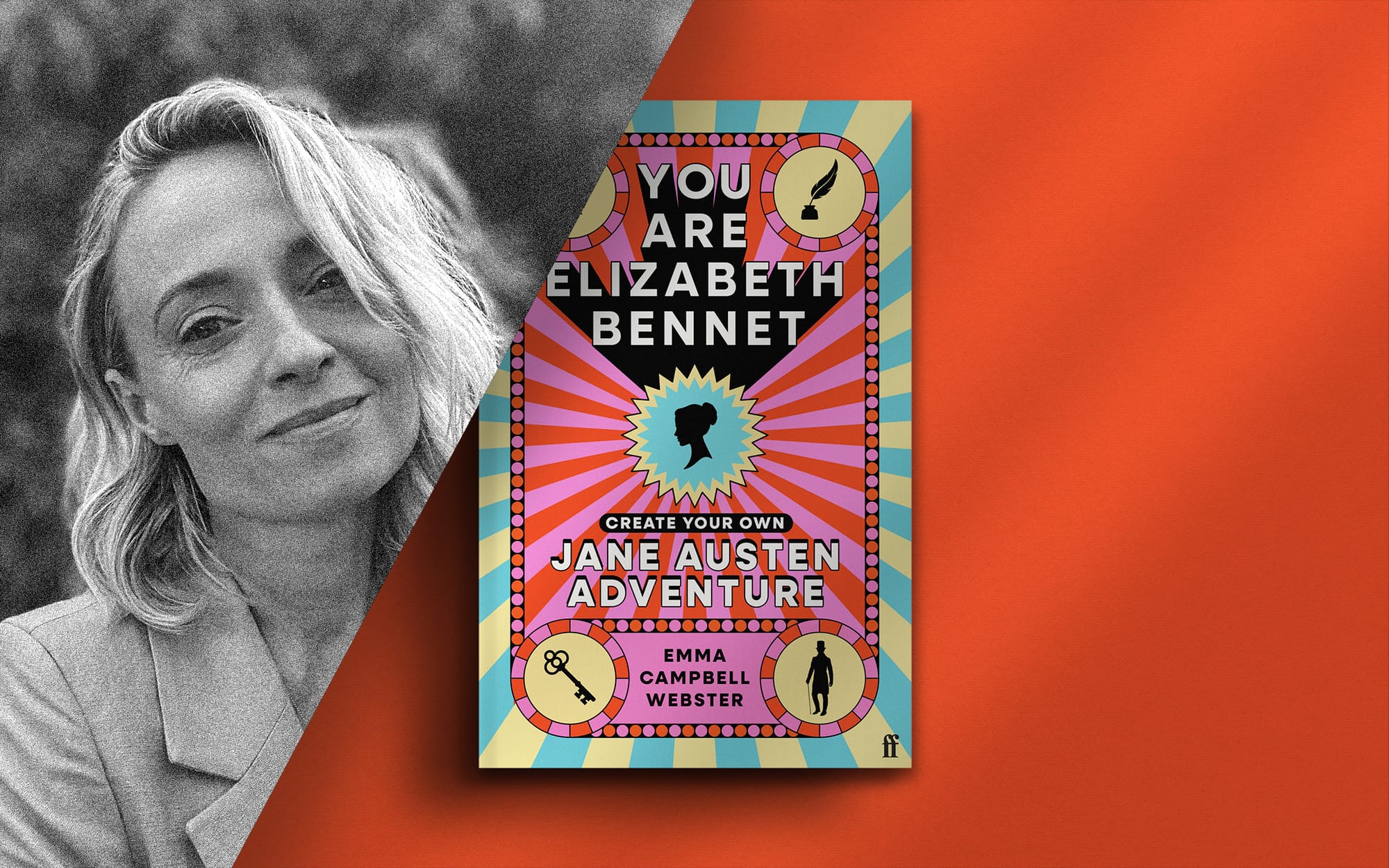

You Are Elizabeth Bennet

The author Emma Campbell Webster invites you to step into a Jane Austen novel

Jane Austen's novels tell stories about people getting married. There are good matches and bad matches and, for young ladies aged between 16 and 27, much depends on making the right choices.

Here Emma Campbell Webster, the author of the playful, interactive book You Are Elizabeth Bennet, tells us more about what it was like to be a young lady in Austen's time.

Questions by Peter Moore

Unseen Histories

Jane Austen is known for her mazy plots when little blunders or twists of fate often appear to send the plot off in an unexpected direction. There’s a similar process at work in your book, You Are Elizabeth Bennet. Can you tell us a little about this?

Emma Campbell Webster

Yes, my book combines all of Austen’s works, and some details from her own life story, into an interactive mission where the reader’s choices determine in which direction the narrative goes next.

The original idea for the book arrived, as they often do, fully formed and without any conceptual agenda beyond the delight of combining these two forms. As I got deeper into the writing process, however, I realized just how significant the idea of ‘choice’ is in Austen.

She often places her heroines at a disadvantage whether that’s financially, socially, in terms of accomplishments, or sometimes even in intelligence or at least maturity, and the act of saying yes or no to limited choices offered her by society, or by men, is often the only agency she has.

In a context like this, a little blunder or twist of fate can have outsized consequences. In You Are Elizabeth Bennet I take this a step further, by having the choices send Elizabeth off into an entirely different narrative from one of Austen’s other novels.

In many ways it’s like a Regency era multiverse, with multiple parallel timelines, and the act of making a choice becomes the mechanism by which the reader jumps between them. I think it’s a feeling we can all relate to – the idea that there are these tiny decisions we made in our past that sent our lives off into a completely new and unexpected direction.

The difference with the book of course is that if you don’t like the outcome, you can go back and choose again! I’m sure most of us have at least one decision we wish we could undo …

Unseen Histories

Structuring the book must have been a huge and beautiful challenge. Can you tell us how you did it?

Emma Campbell Webster

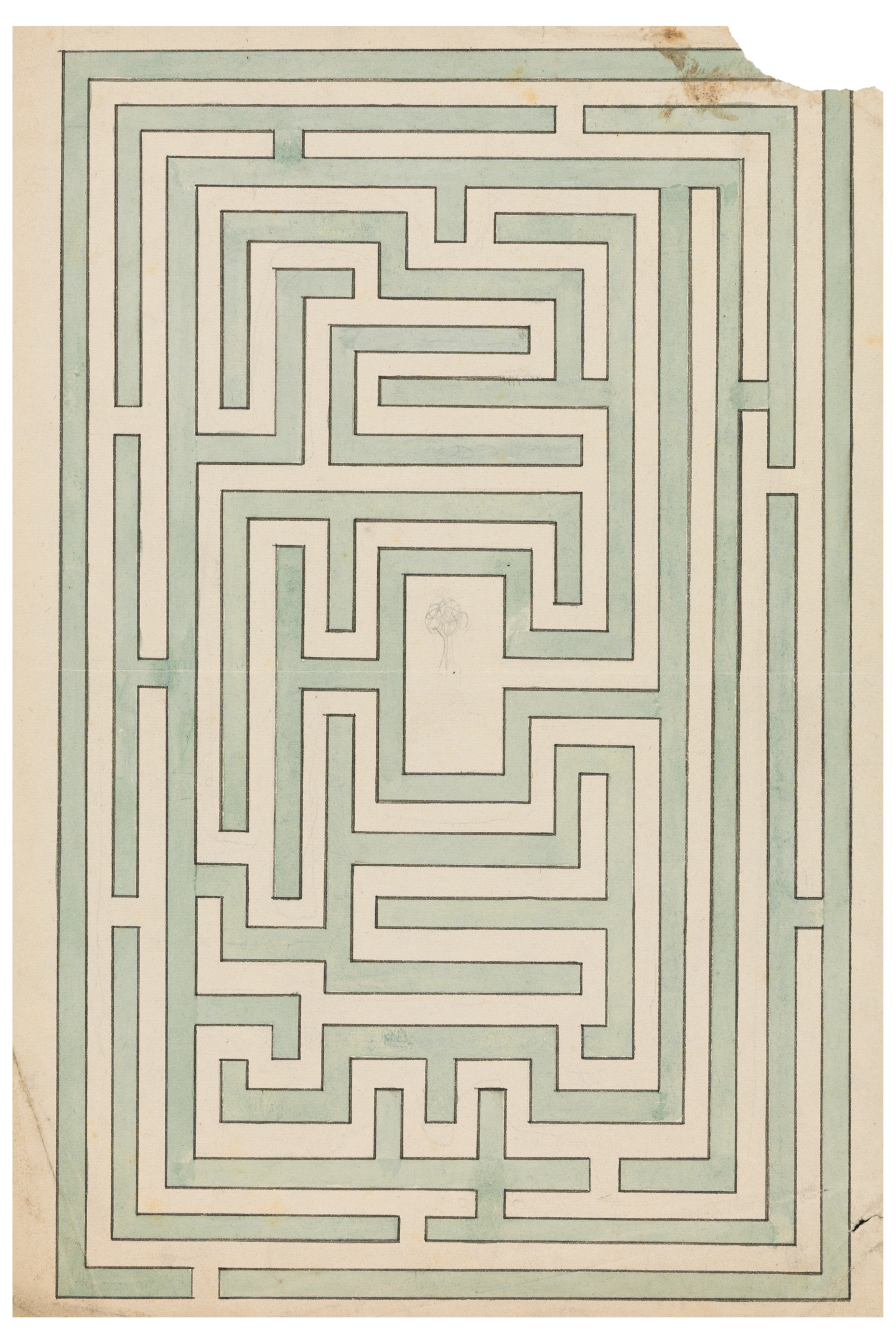

Before I started, I imagined that these types of books must be extraordinarily complicated and was quite daunted. I started by buying some old children’s books written in this style from eBay and mapped them out on a big piece of paper.

I quickly realized that they weren’t quite as complicated as I thought, and usually just branched off in different unconnected directions. I decided to have a little more fun with mine and find ways to weave the narrative sub-branches back to the main Pride and Prejudice throughline.

I plotted it all out in a big piece of paper which I then taped to my wall next to my desk for reference. I’m quite a visual person and really enjoyed this element of the process. The editor, Henry Eliot, also had to draw his own map to keep track of the impact of any proposed changes, and in this era of AI and digital everything, I found the sight of these pencil-drawn maps especially delightful.

Unseen Histories

The late Georgian world in which Austen’s novels are set is an enchanting one. What parts of it appeal to you?

Emma Campbell Webster

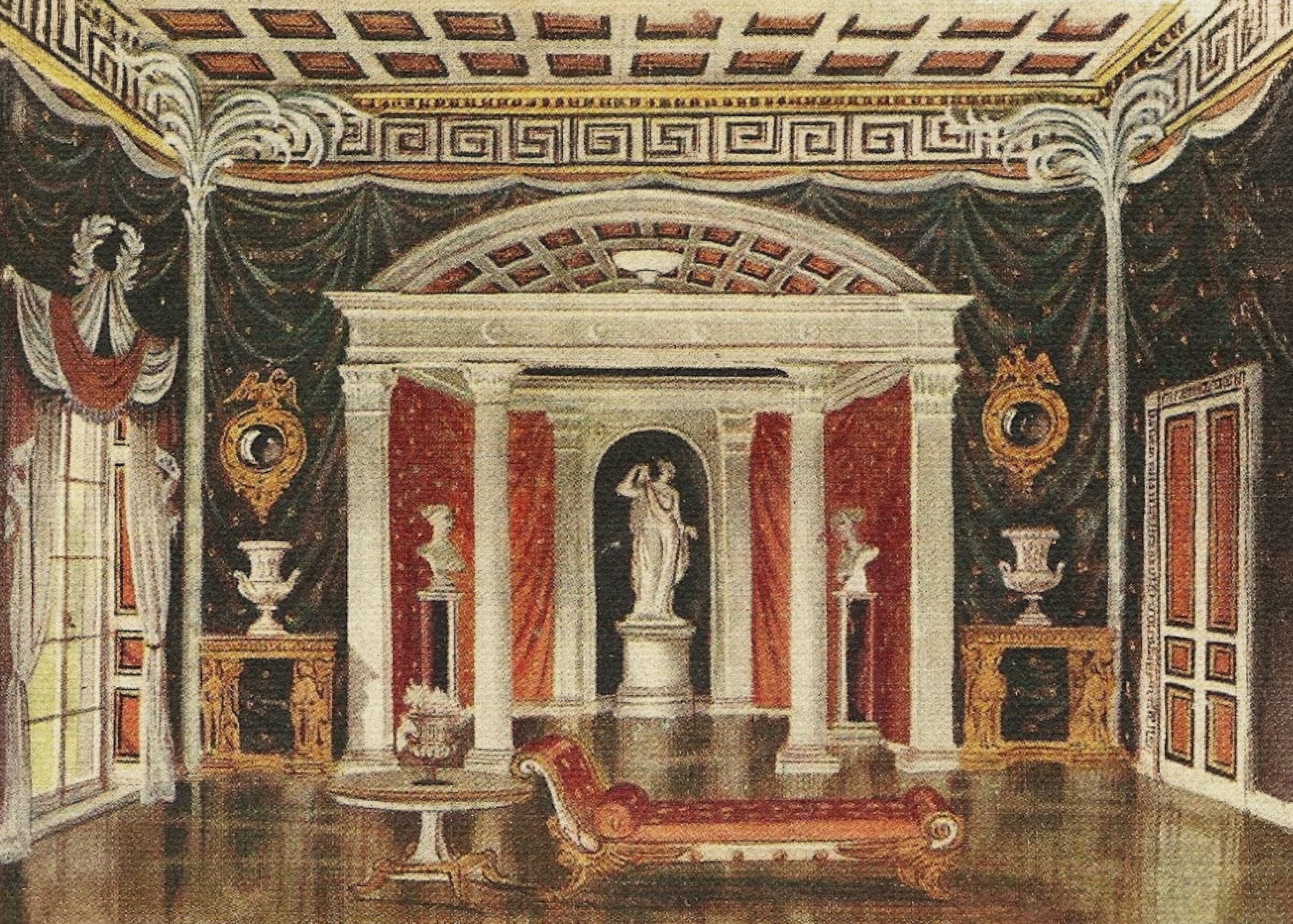

Where to begin? There is so much that appeals, from the slower pace of life to the sense of community – Austen’s famous ‘three or four families in a country setting’ – to the beauty of the architecture and the unspoiled rural landscapes in which they are set.

I think the most enchanting quality however is that of restraint. In Persuasion, when Austen has Captain Wentworth wordlessly help Anne Elliot into the carriage at the end of a long and exhausting walk, both we and Anne feel and interpret an extraordinary amount.

As a reader, this makes for a delicious experience and is a welcome contrast to the sensory overload of much of the media we consume today.

Unseen Histories

The ‘mission’ you sketch out at the beginning is, through astute choices, ‘to marry prudently and for love’. Was this really the only future possible for young ladies in Austen’s time?

Emma Campbell Webster

Well, obviously it wasn’t for Austen herself, which is part of what makes her so extraordinary. It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like to buck convention in that way at that time. For many women however, unless they had their own independent income, this really was their only option.

What marks Elizabeth Bennet out as unusual of course is that she insists on marrying for love and not just financial and social stability, and it’s this tension that’s so beautifully dramatized in the contrast between her decisions and those of her childhood friend Charlotte Lucas.

Unseen Histories

Elizabeth Bennet (or ‘Miss Eliza’, or ‘Lizzy’) is beloved by readers partly because she is such an astute player of this game. She also has the honour of winning it too by marrying Mr Darcy. When did you first read her story in Pride and Prejudice and what effect did it have on you?

Emma Campbell Webster

Well, I first encountered her story visually in the 1995 BBC adaptation, and any subsequent readings of the book have undoubtedly been indelibly marked by this first impression.

What I do remember being most struck and inspired by as a young woman was the fact that it is Lizzy’s wit and intelligence that allow her to rise above her situation and be seen for who she is as an individual separate from any perception of the ‘circumstances of her birth’ or her family of origin. I think it’s this that has resonated with female readers in the centuries since.

Unseen Histories

Is it true that Austen was sparing in her description of Lizzy? If so, does that give her character an intriguing flexibility?

Emma Campbell Webster

I think that’s an interesting idea, and perhaps one of the reasons it’s so easy for readers of Pride and Prejudice to identify so strongly with her. I also think it emphasizes Elizabeth’s mind and wit, since these are what are necessarily foregrounded when physical descriptions are sparse.

It’s worth remembering that in the book she is not perceived by others to be particularly beautiful—her own mother describes her as ‘not half so handsome as’ her sister Jane, and Mr. Darcy famously considers her ‘tolerable: but not handsome enough to tempt me’.

This can be hard to remember when we are primed by Hollywood to picture Jennifer Ehle or Keira Knightley as Lizzy, and I think it would be exciting if one day a production was daring enough to cast an actress less conventionally beautiful in the role, since this would further highlight the extraordinary allure of her other qualities in the eventual match between her and Darcy.

Unseen Histories

One settled characteristic that you play upon is her daring streak. She sets determinedly off across the fields at one point, vaulting over stiles and leaping over muddy puddles. She then spars with the forbidding Mr Darcy in conversation. In so doing was she shattering Georgian social conventions?

Emma Campbell Webster

By all accounts, yes (it’s hard to know for sure what women were getting up to outside of what was recorded, especially since the records were usually kept by men). It’s clear from the context of the novel itself, and the reactions of Mrs. Bingley and Mrs. Hurst, and even Darcy at first, that Elizabeth does not abide by conventional social norms.

One quality that really shines through is that of her physical vitality, which Austen so brilliantly captures in the scene where she arrives with muddy hems but bright eyes into the staid scene at Netherfield.

Even vaulting over stiles is representative of a refusal to be limited by the man-made boundaries imposed on a once-wild natural landscape. Austen’s skill lies in conveying all this with the lightest of brushstrokes, yet the images she renders linger in the mind throughout the novel and well beyond.

Unseen Histories

‘I'm looking for a man in finance, Trust fund, 6'5", blue eyes ...’, runs the recent TikTok hit. What was the imagined paragon for young ladies in the early nineteenth century? And how many such individuals existed?

Emma Campbell Webster

Firstly, can we just agree that this would surely be Miss Bingley’s go-to karaoke number?

To answer the question more directly, I think the common thread here is the idea of the economics of love. Whilst the chances of finding someone 6’5” in 19th century England were pretty slim, when Mr. Darcy is first introduced his is nevertheless described as drawing the attention of the room by his ‘fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien, and the report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year’, which is remarkably similar to the song’s refrain.

Both are tongue-in-cheek, but both point to an underlying truth that regrettably is almost as true today as it was in Austen’s time—that economic inequality between the sexes often means a woman’s greatest chance of achieving financial stability is still to marry into it.

Unseen Histories

Readers today might be startled to know how young girls were when they were considered to be coming into their bloom and of marriageable age. Would it be fair to say that Lydia (who ran off with Mr Wickham) was at the lower end of the spectrum and Elizabeth towards the top?

Emma Campbell Webster

Yes, to an extent. It’s strongly implied that Lydia is too young to be getting married, though it was legal with parental consent. At twenty-one, Lizzy is considered a more appropriate age, though Lady Catherine famously disapproves of all the Bennet sisters being out at once.

One detail I find particularly striking is the spectre of a woman turning twenty-seven and being unmarried, which haunts Austen’s narratives. This drives Charlotte Lucas to accept Mr. Collins, is the age Anne Elliot is at the beginning of Persuasion when it seems all hope of marital happiness is lost to her, and Austen herself was on the cusp of her twenty-seventh birthday when she accepted, even if only for one night, a proposal of marriage from an eligible man she did not love.

I can’t help but think of the idea of the ‘27 club’ in contemporary culture—the informal list of musicians and other celebrities who died at the age of 27. In Austen’s world, it seems to represent the death of a woman’s marriageability, and that is one thing that is probably harder for a contemporary audience to relate to, since the average age to get married is now much closer to 30.

Unseen Histories

Respectability is a central concept for Austen. What did it mean and do you think it is an easy concept for us to grasp today?

Emma Campbell Webster

For Austen, it was a nuanced quality that combined social status, wealth, and ‘good breeding’ with intelligence, moral standing, decorum, and ‘good sense’. I think we feel in Austen’s novels the ever-present threat, particularly for women, of losing respectability, a fate that could prove ruinous to any hope of making a ‘prudent’ marriage.

When viewed that way it can feel archaic and irrelevant to present day romantic life, yet clear echoes remain in the swift and devastating effects of contemporary ‘cancel culture’ and its power to tarnish professional reputations for life, so I do think we have parallels that allow us to imagine the weight it carried for Austen’s characters and contemporary audience •

This interview was originally published October 23, 2025.

You Are Elizabeth Bennet: Create Your Own Jane Austen Adventure

Faber, 9 October 2025

RRP: £10 | ISBN: 978-0571397907

Is it a truth universally acknowledged that a young Austen heroine must be in want of a husband?

You are in the world of a Jane Austen novel. As the events of Pride and Prejudice – and Austen's other novels – start to unfold around you, you must choose your own path, avoiding social scandal and unsuitable engagements, and write your own destiny, whether it's to marry a single man in possession of a good fortune or to become a famous author yourself.

A witty and irreverent celebration of Jane Austen and her novels, this literary game will test all your powers of propriety and prudence.

With thanks to Lily Birch and Sophie Portas.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store